Creating Resort Towns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phony Colonee These Motels Contained Colonial- Themed Architecture, Featuring Red Brick Facades, Cupolas Or Turret Crowned Roofs

n the eyes of some, it is as tacky as a plastic pink flamingo on a front lawn in a trailer park. To others, it is a fun, if idealized, throwback to a better Itime. However you view it, there is no doubt it is one of the Garden State’s somewhat underappreciated influences on the world of architecture. Known as Doo-Wop, it found a unique expression that came of age along with a generation of New Jerseyans in the motels of Wildwoods. The Wildwoods You wouldn’t know it to look at it today, but New Jersey’s Wildwoods were once, indeed, a tangle of wild woods. They sit on a six mile long barrier island near the southern tip of the state at Exit 4 on the Garden State Parkway. When one says “The Wildwoods,” they refer collectively to three separate municipalities: North Wildwood, Wildwood, and Wildwood Crest. They were founded by developers between 1880 and 1905, notably including Frederick Swope and his Five Mile Beach Improvement Company, Philip Pontius Baker and his Wildwood Beach Improvement Company, and John Burk with the Holly Beach Improvement Company. All saw the It might be hard to believe now, but The Wildwoods are named island’s potential in terms of the ideal summer resort, or “Cottage Colony.” after woods that were indeed The small fishing village of Anglesea was the first to be founded in 1880, wild. Note the tree in the followed by Wildwood in 1890. In 1906, Anglesea was then repackaged as foreground bent to grow into a letter “W”! the island’s first specifically resort town and renamed North Wildwood. -

Trend Report on Travel After 2020

in collaboration with GLOBETRENDER Travel Trend Report October 2020 travel after 2020 what will tourism look like in our new reality? table of contents Co-authors Damon Embling World Affairs Reporter, Euronews Damon is a seasoned journalist, specialising in travel and tourism. He regularly reports from key global industry events including ITB Berlin and WTM London and moderates high-profile debates on the future of the sectors. Most recently, these have included a special virtual series for Euronews and a debate session for Brand USA Travel Week Europe 2020. Damon has also presented several travel programmes for Euronews, from across Europe and Asia. Jenny Southan, Editor & Founder of travel trend forecasting agency Globetrender Jenny Southan is editor and founder of Globetrender, a travel trend forecasting agency and online magazine dedicated to the future of travel. Jenny is also a public speaker and freelance journalist who writes for publications including Conde Nast Traveller, The Telegraph and Mr Porter. Previously she was features editor of Business Traveller magazine for ten years. Contributor Eva zu Beck Euronews Travel Contributor Eva zu Beck is an adventure YouTuber and travel TV host with a community of 2 million fans across her social media channels. She travels to countries rarely covered by mainstream media, and tells the stories of overcoming challenges in some of the planet’s most remote places. table of contents 2 introduction Hit hard by the global Covid-19 pandemic, the travel and tourism sectors are facing a rapidly changing future. As brands and businesses look to recover losses, there’s also a need to re-think their offerings, amid changing consumer behaviour and habits. -

Three Perfect Days

No matter how many passport stamps you’ve collected, visiting Costa Rica presents a challenge. What seems so small and straightforward on paper—a traveler-friendly nation that’s dwarfed by West Virginia—feels larger than life once you’re on the ground. The seas on either side are separated by rugged mountain ranges, complete with fire-spitting volcanoes and mist-shrouded cloud forests. And the country’s dozen or so distinct ecological zones— which are heavily protected and together account for 5 percent of the world’s biodiversity, including jaguars, sloths, and more than 1,200 species of butterfly—are also home to an abundance of microclimates, each of which has little regard for your plans. It excites the imagination, but also forces hard decisions: Absorb the culture of bustling San José, spy on treetop monkeys on Volcán Arenal, or dive into the cobalt-blue Pacific on Guanacaste’s Gold Coast? You’ll be in a rush to do it all, but remember to slow down. It’s only then that you’ll discover the state of being known as pura Three vida—the true source of Costa Rica’s wealth. Perfect Days Costa Rica By Peter Koch Photography by Matthew Johnson 56 57 56-69_HEMI1019_3PD_3_R1.indd 56 06/09/2019 10:11 56-69_HEMI1019_3PD_3_R1.indd 57 06/09/2019 10:11 DAY 11,260-foot-tall volcano, loom- original intent was to give all with embroidered first com- ing over the skyline. San José is Costa Ricans access to high- munion dresses, Technicolor perched at 3,845 feet above sea brow culture; admission was floral displays, and growers of level, in the mountain-fringed just one colón. -

Report Template Normal Planning Appeal

Inspector’s Report 300440-17 Development The construction of a single storey discount foodstore (to include off licence use). The development includes the erection of signage. The proposed development will be served by 112 no. car parking spaces with vehicular/pedestrian access will be provided from the Strand Road. The proposed development includes the construction of a single storey ESB sub station, lighting, all landscaping, boundary treatment and site development works. Location Strand Road, Tramore, County Waterford. Planning Authority Waterford City and County Council. Planning Authority Reg. Ref. 17/697. Applicant Aldi Stores Ltd. Type of Application Permission. Planning Authority Decision Refusal of permission. ABP300440-17 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 35 Type of Appeal First Party Appellant Aldi Stores Ltd. Observer Leefield Ltd. Date of Site Inspection 21st August 2018. Inspector Derek Daly. ABP300440-17 Inspector’s Report Page 2 of 35 1.0 Site Location and Description 1.1. The appeal site is within the built up area of the town of Tramore in relative close proximity to both the town centre and the beachfront. The site is currently vacant with no active use on the site. 1.2. The site has a stated area of 1.02 hectares and is irregular in configuration. The site has road frontage onto Strand Road to the south and southwest. The site also incorporates a roadway off Strand Road referred to as Crescent Road which loops in a semi circular manner around the rear of a number of properties fronting onto Strand Road. This roadway provides access for the site. -

Sex Tourism: Do Women Do It Too?

Leisure Studies ISSN: 0261-4367 (Print) 1466-4496 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rlst20 Sex tourism: do women do it too? Sheila Jeffreys To cite this article: Sheila Jeffreys (2003) Sex tourism: do women do it too?, Leisure Studies, 22:3, 223-238, DOI: 10.1080/026143603200075452 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/026143603200075452 Published online: 01 Dec 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 3869 View related articles Citing articles: 60 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rlst20 Leisure Studies 22 (July 2003) 223–238 Sex tourism: do women do it too? SHEILA JEFFREYS Department of Political Science, The University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia This article examines a recent tendency amongst researchers of sex tourism to include women within the ranks of sex tourists in destinations such as the Caribbean and Indonesia. It argues that a careful attention to the power relations, context, meanings and effects of the behaviours of male and female tourists who engage in sexual relations with local people, makes it clear that the differences are profound. The similarities and differences are analysed here with the conclusion that it is the different positions of men and women in the sex class hierarchy that create such differences. The political ideas that influence the major protagonists in this debate to include or exclude women will be examined. The article ends with a consideration of the problematic implications of arguing that women do it too. -

Rental Guidelines

Rental Guidelines The guest, including all members of the guest’s party understands and agrees: Upon confirming a reservation, a contractual agreement is made between Resort Vacation Properties of St. George Island, Inc. and the guest, including all members of the guest’s party. The guest and the rest of their party agree to abide by the following Rental Guidelines: Maximum Occupancy: At all times, both inside and outside the home, the maximum occupancy is the number of persons allowed on the premises, including infants. We cater to family groups and cannot accept reservations for vacationing students or house parties. We do not rent to students even if one or more parents or legally responsible adults accompany them, or to groups under the age of 25. This policy is strictly enforced. Special events such as weddings, reunions, and church retreats are only allowed in select homes and require a separate contract. Special pricing and security deposits may be required. Please contact our office for details. Pets: Guests may bring up to 2 pets to our pet-friendly homes unless otherwise noted in an individual property description. Guests must obtain special permission, and a fee of $100 will be charged, for each pet that exceeds the amount allowed as outlined above or as specified in an individual property description. Guests are required to clean up after their pets, and there may be additional charges if pet waste is left on the property. Franklin County law prohibits leaving pet waste on the beach or dunes. Pets in non-pet-friendly homes are strictly prohibited and will result in immediate eviction with no refund of rent. -

Twixt Ocean and Pines : the Seaside Resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1996 Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Souther, Jonathan Mark, "Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930" (1996). Master's Theses. Paper 1037. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWIXT OCEAN AND PINES: THE SEASIDE RESORT AT VIRGINIA BEACH, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Master of Arts University of Richmond, 1996 Robert C. Kenzer, Thesis Director This thesis descnbes the first fifty years of the creation of Virginia Beach as a seaside resort. It demonstrates the importance of railroads in promoting the resort and suggests that Virginia Beach followed a similar developmental pattern to that of other ocean resorts, particularly those ofthe famous New Jersey shore. Virginia Beach, plagued by infrastructure deficiencies and overshadowed by nearby Ocean View, did not stabilize until its promoters shifted their attention from wealthy northerners to Tidewater area residents. After experiencing difficulties exacerbated by the Panic of 1893, the burning of its premier hotel in 1907, and the hesitation bred by the Spanish American War and World War I, Virginia Beach enjoyed robust growth during the 1920s. While Virginia Beach is often perceived as a post- World War II community, this thesis argues that its prewar foundation was critical to its subsequent rise to become the largest city in Virginia. -

Ideology and Utopia Along the Backpacker Trail

Responsibly Engaged: Ideology and Utopia along the Backpacker Trail By Sonja Bohn Submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology (2012) Abstract By following the backpacker trail beyond the „tourist bubble,‟ travellers invest in the ideals of freedom, engagement, and responsibility. Backpacker discourse foregrounds travellers‟ freedom to mobility as it constructs the world as „tourable‟; engagement is demonstrated in the search for „authentic‟ connections with cultural Others, beyond the reach of globalised capitalism; responsibility is shouldered by yearning to improve the lives of these Others, through capitalist development. While backpackers frequently question the attainability of these ideals, aspiring to them reveals a desire for a world that is open, diverse, and egalitarian. My perspective is framed by Fredric Jameson‟s reading of the interrelated concepts of ideology and utopia. While backpacker discourse functions ideologically to reify and obscure global inequalities, to entrench free market capitalism, and to limit the imagining of alternatives, it also figures for a utopian world in which such ideology is not necessary. Using this approach, I attempt to undertake critique of backpacker ideology without invalidating its utopian content, while seeking to reveal its limits. Overall, I suggest that late- capitalism subsumes utopian desires for a better way of living by presenting itself as the solution. This leaves backpackers feeling stranded, seeking to escape the ills of capitalism, via capitalism. ii Acknowledgements I am grateful to the backpackers who generously shared their travel stories and reflections for the purposes of this research, I wish you well on your future journeys. -

Global Trends in Coastal Tourism

CESD: Global Trends in Coastal Tourism Global Trends in Coastal Tourism Prepared by: Martha Honey, Ph.D. and David Krantz, M.A. Center on Ecotourism and Sustainable Development A Nonprofit Research Organization Stanford University and Washington, DC Prepared for: Marine Program World Wildlife Fund Washington, DC December 2007 1 CESD: Global Trends in Coastal Tourism TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms.......................................................................................... 5 1.0 Executive Summary: Key Findings........................................... 8 2.0 WWF Working Hypothesis...................................................... 15 3.0 CESD Research ........................................................................ 15 4.0 Global Tourism Trends ............................................................ 16 4.1 Importance of Tourism............................................................................16 4.2 Environmental Impacts...........................................................................17 4.3 Market Trends in the New Millennium: 2000-2020 ................................24 5.0 Types of Tourism and Definitions........................................... 28 5.1 Beach Resort, Cruise, Ecotourism, Sustainable Tourism ...................28 5.2 History and Importance of Ecotourism and Sustainable Tourism......29 5.3 Consumer Demand for Ecotourism and Sustainable Tourism............33 6.0 Structure of the Tourism Industry .......................................... 35 6.1 Airlines .....................................................................................................38 -

Enjoying Your Vacation Options

Enjoying Your Vacation Options Marriott Vacation Club® has created the most flexible and exciting vacation ownership program available—the Marriott Vacation Club Destinations™ program. This guide will help you understand and maximize your options. As a Marriott Vacation Club Destinations Owner and through the Marriott Vacation Club Destinations Exchange Program, you can use Vacation Club Points for a variety of experiences within four flexible collections of vacation options: Marriott Vacation Club® Resorts – Enjoy a vacation at any of more than 50 Marriott Vacation Club resorts in the U.S., the Caribbean, Europe and Asia. Marriott Rewards® – Redeem your Vacation Club Points for Marriott Rewards points and stay at more than 3,800 Marriott® hotels worldwide. Explorer Collection – Discover unique travel opportunities and adventures, including cruises, safaris, rafting, mountain biking and guided tours. Exchange Partner Resorts – Vacation at hundreds of resorts in dozens of locations through our external exchange partner, Interval International®. With all this flexibility, you have virtually limitless possibilities! OPTION 1: MARRIOTT VACATION CLUB RESORTS Choose a spacious vacation villa for your next getaway. When you plan a vacation within Marriott Vacation Club Resorts, you will have access to more than 50 magnificent resorts offering spacious accommodations, from deluxe studios to 1- and 2-bedroom villas and even 3-bedroom villas and townhouses, depending on the location. Stretch out and enjoy all the comforts of home with amenities such as a fully equipped kitchen, washer and dryer, a balcony or patio, and separate living and dining areas.1 Vacationing at a Marriott Vacation Club resort is perfect for extended vacations or family reunions. -

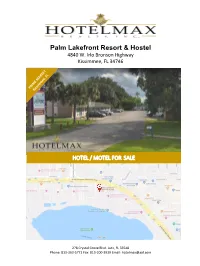

Palm Lakefront Resort & Hostel

Palm Lakefront Resort & Hostel 4840 W. Irlo Bronson Highway Kissimmee, FL 34746 HOTEL / MOTEL FOR SALE 278 Crystal Grove Blvd. Lutz, FL 33548 Phone: 813-363-5771 Fax: 813-200-3939 Email: [email protected] 4840 W. Irlo Bronson Highway Kissimmee, FL 34746 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4840 W. Irlo Bronson Highway Kissimmee, FL 34746 County: Osceola Property Type: Hotel/Motel No. of Buildings: 4 No. of Stories: 1 m No. of Units/Rooms: 50 .co Building Area Size: 7,372 Sq. Ft. Lot Size/Acres: 4.24 Acres Year Built: 1978 Pool: Yes Zoned: Commercial CONTACT LISTING BROKER- Price: Signed NDA Required HotelMaxRealty CONFIDENTIAL LISTING – DO NOT CONTACT OWNER OR EMPLOYEES CONFIDENTIAL SALE Property is centrally located near Orlando Theme Parks Must schedule appointment with listing agent to visit www.hostelinorlando.com www. property – Terry Hatfield – 813-363-5771 2 Property Description 3 The Palm Lakefront Resort and Hostel is a 50 Unit, inn-style relaxed hostel that is beautifully landscaped with lush gardens, tropical trees and old Florida character. The lakefront walking pier is a reflection of the picturesque sitting along Lake Cecile and offers all of nature’s delight. A beautiful swimming pool overlooks the lake and tropical grounds surrounded by large, Florida ancient oaks and statue-oriented fountains. The hostel offers free Wi-Fi, exercise area, swimming pool, outdoor fire pit, picnic areas, BBQ facilities, canoeing, game room with Karaoke, ping pong, pool tables and foosball tables, badminton equipment, board games, a commercial laundry. The hostel has a kitchen where guests may cook their own food. Location Description Off Interstate 4 and US-192, this hostel is 14 miles from the Universal Orlando Theme Park, 8 miles from SeaWorld Orlando and 5 miles from the Walt Disney World Resort. -

New England Vacations

NewBest England Vacations 1 NEW ENGLAND TODAY Index Things to Do in Boston Classic Boston Attractions..........................................................................................2 Explore Beacon Hill........................................................................................................3 Explore Swan Boats........................................................................................................4 Maine Vacations The 5 Best Photo Ops in Acadia National Park.....................................................6 10 Prettiest Coastal Towns In Maine........................................................................7 Where to Spot Moose in Maine...................................................................................8 Best of Mount Desert Island.........................................................................................8 Explore York Beach, Maine.........................................................................................10 Things to Do in New Hampshire Best Classic Attractions in New Hampshire......................................................12 Best of the White Mountains...................................................................................13 Best of the NH Seacoast.............................................................................................14 Best Scenic Hikes in the White Mountains.........................................................16 Explore Mt. Washington Cog Railroad.................................................................17