The Practice of Typography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inland Foundry

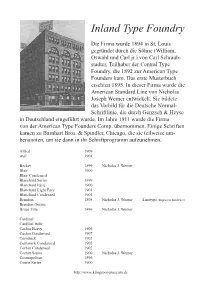

Inland Type Foundry Die Firma wurde 1894 in St. Louis gegründet durch die Söhne (William, Oswald und Carl jr.) von Carl Schraub- stadter, Teilhaber der Central Type Foundry, die 1892 zur American Type Founders kam. Das erste Musterbuch erschien 1895. In dieser Firma wurde die American Standard Line von Nicholas Joseph Werner entwickelt. Sie bildete das Vorbild für die Deutsche Normal- Schriftlinie, die durch Genzsch & Heyse in Deutschland eingeführt wurde. Im Jahre 1911 wurde die Firma von der American Type Founders Comp. übernommen. Einige Schriften kamen zu Barnhart Bros. & Spindler, Chicago, die sie teilweise um- benannten, um sie dann in ihr Schriftprogramm aufzunehmen. Alfred 1909 Avil 1904 Becker 1899 Nicholas J. Werner Blair 1900 Blair Condensed Blanchard Series 1899 Blanchard Italic 1900 Blanchard Light Face 1901 Blanchard Condensed 1901 Brandon 1898 Nicholas J. Werner Linotype (Engravers Bold Face) Brandon Gothic Bruce Title 1896 Nicholas J. Werner Cardinal Cardinal Italic Caslon Heavy 1906 Caslon Condensed 1907 Comstock 1902 Comstock Condensed 1905 Corbitt Condensed 1902 Corbitt Series 1900 Nicholas J. Werner Cosmopolitan 1896 Courts Series 1900 http://www.klingspor-museum.de Dorsey Series 1904 Dorsey Light Dorsey Light Italic 1910 Dorsey Condensed 1910 Dorsey Extra Condensed 1910 Drew Series 1910 Edwards Series vor 1899 Faust 1899 Foster 1905 William A. Schraubstadter Foster Condensed 1908 Francis 1904 Gothic No. 8 vor 1900 Nicholas J. Werner Haight 1902 A. V. Haight Havens Series 1902 Hearst 1902 Solotype Hearst Italic 1903 -

Introduction by the Editor

INTRODUCTION BYTHE EDITOR HEN Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne- Jones, William Morris, and some fellow-artists painted on the damp walls of the Oxford Un- ion debating hall in 1857, their ignorance of fresco technique led them to produce haunt- ing images of the Middle Ages which, in ghostly fashion, began to fade almost immedi- ately; but the more permanent legacy of this episode was a body of richly revealing anecdotes about the Pre- Raphaelites themselves. Burne-Jones, for example, recalled that Mor- ris was so fanatically precise about the details of medieval costume Figure 1 that he arranged for "a stout little smith" in Oxford to produce a suit of armor which the painters could use as a model. When the basinet arrived, Morris at once tried it on, and Burne-Jones, working high above, looked down and was startled to see his friend "embedded in iron, dancing with rage and roaring inside" because the visor would not lift.1 This picture of Morris imprisoned and blinded by a piece of medie- val armor is an intriguing one: certainly it hints at an interpretation of his career that is not very flattering. But we ought to set alongside it another anecdote, from the last decade of Morris's life, the symbol- ism of which seems equally potent. Early in November 1892, young Sydney Cockerell, recently hired by Morris to catalogue his incunab- ula and medieval manuscripts, spent the entire day immersed in that remote age while studying materials in Morris's library. As evening approached, he emerged again into the nineteenth century (or so he thought) and climbed the staircase of Kelmscott House: "When I went up into the drawing room to say goodnight Morris and his wife were playing at draughts, with large ivory pieces, red and white. -

Abstracts Povzetki

PLACES, SPACES AND THE PRINTING PRESS: IMPRINTING REGIONAL IDENTITIES KRAJI, PROSTORI IN TISKARNE: ODTISI REGIONALNIH IDENTITET INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC ONLINE CONFERENCE MEDNARODNA ZNANSTVENA KONFERENCA NA SPLETU 24. MAREC 2021 EDITORIAL BOARD dr. Ines Vodopivec dr. Caroline Archer-Parré Žiga Cerkvenik Maj Blatnik Jana Mahorčič Tomaž Bešter ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Žiga Cerkvenik Maj Blatnik ORGANIZERS Centre for Printing History and Culture at Birmingham City University at University of Birmingham, United Kingdom / Center za tiskarsko zgodovino in kulturo na Mestni univerzi Birmingham, Združeno kraljestvo National and University Library, Ljubljana, Slovenia / Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana, Slovenija. PUBLISHED BY NATIONAL AND UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA Publication is available online in PDF format at: Publikacija je dostopna v PDF formatu na spletni strani: http://www.dlib.si/details/URN:NBN:SI:doc-PDMSAPDI/ 24. 3. 2021 National and University Library, Ljubljana, copyright 2021 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. 2 THE CONFERENCE THEME ‘Place’ is a physical entity and relates to specific locations—geographical or architectural—where particular activities are conducted. ‘Space’, on the other hand, is abstract; it is the intellectual, cultural and experiential environment in which individuals or groups congregate and collaborate. Place and space are significant to the progress of all trades, but, with the exception of the James Raven’s Bookscape: geographies of printing and publishing in London, these concepts have generally been overlooked when it comes to printing and the products of the press. -

Kemble Z3 Ephemera Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c818377r No online items Kemble Ephemera Collection Z3 Finding aid prepared by Jaime Henderson California Historical Society 678 Mission Street San Francisco, CA, 94105-4014 (415) 357-1848 [email protected] 2013 Kemble Ephemera Collection Z3 Kemble Z3 1 Title: Kemble Z3 Ephemera Collection Date (inclusive): 1802-2013 Date (bulk): 1900-1970 Collection Identifier: Kemble Z3 Extent: 185 boxes, 19 oversize boxes, 4 oversize folder (137 linear feet) Repository: California Historical Society 678 Mission Street San Francisco, CA 94105 415-357-1848 [email protected] URL: http://www.californiahistoricalsociety.org Location of Materials: Collection is stored onsite. Language of Materials: Collection materials are primarily in English. Abstract: The collection comprises a wide variety of ephemera pertaining to printing practice, culture, and history in the Western Hemisphere. Dating from 1802 to 2013, the collection includes ephemera created by or relating to booksellers, printers, lithographers, stationers, engravers, publishers, type designers, book designers, bookbinders, artists, illustrators, typographers, librarians, newspaper editors, and book collectors; bookselling and bookstores, including new, used, rare and antiquarian books; printing, printing presses, printing history, and printing equipment and supplies; lithography; type and type-founding; bookbinding; newspaper publishing; and graphic design. Types of ephemera include advertisements, announcements, annual reports, brochures, clippings, invitations, trade catalogs, newspapers, programs, promotional materials, prospectuses, broadsides, greeting cards, bookmarks, fliers, business cards, pamphlets, newsletters, price lists, bookplates, periodicals, posters, receipts, obituaries, direct mail advertising, book catalogs, and type specimens. Materials printed by members of Moxon Chappel, a San Francisco-area group of private press printers, are extensive. Access Collection is open for research. -

A Catalogue of the Wood Type at Rochester Institute of Technology David P

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 11-1-1992 A Catalogue of the wood type at Rochester Institute of Technology David P. Wall Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Wall, David P., "A Catalogue of the wood type at Rochester Institute of Technology" (1992). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School ofPrinting Management and Sciences Rochester Institute ofTechnology Rochester, New York Certificate ofApproval Master's Thesis This is to Certify that the Master's Thesis of David P. Wall With a major in Graphic Arts Publishing has been approved by the Thesis Committee as satisfactory for the thesis requirement for the Master ofScience degree at the convocation of DECEMBER 1992 Da,e Thesis Committee: David Pankow Thesis Advisor Marie Freckleton Graduate Program Coordinator George H. Ryan Direcmr or Designa[e A Catalogue of the Wood Type at Rochester Institute of Technology by David P. Wall A thesis project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the School of Printing Management and Sciences in the College of Graphic Arts and Photography of the Rochester Institute ofTechnology November 1992 Project Advisor: Professor David Pankow Introduction type,' When Adobe Systems introduced in 1990 their first digital library of 'wood the event marked the latest step forward in a tradition dating back to 1828, when Darius Wells, ofNew Wells' York City, perfected the equipment and techniques needed to mass produce wood type. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Frick Fine Arts Library

Frick Fine Arts Library William Morris’s The Kelmscott Chaucer & Other Book Arts Library Guide No. 16 "Qui scit ubi scientis sit, ille est proximus habenti." Brunetiere* Before Beginning Research FFAL hours: M-H, 9-9; F, 9-5; Sa-Su, Noon – 5 Hillman Library – Special Collections – 3rd floor: M-F, 9:00 – Noon and 1:00 – 5:00; Closed on weekends. Policies: Food and drink may only be consumed in the building’s cloister and not in the library. Personal Reserve: Undergraduate students may, if working on a class term paper, ask that books be checked out to the “Personal Reserve” area where they will be placed under your name while working on your paper. The materials may not leave the library. Requesting Items: All ULS libraries allow you to request an item that is in the ULS Storage Facillity at no charge by using the Requests Tab in Pitt Cat. Items that are not in the Pitt library system may also be requested from another library that owns them via the Requests tab in Pitt Cat. There is a $5.00 fee for journal articles using this service, but books are free of charge. Photocopying and Printing: There are two photocopiers and one printer in the FFAL Reference Room. One photocopier accepts cash (15 cents per copy) and both are equipped with a reader for the Pitt ID debit card (10 cents per copy). Funds may be added to the cards at a machine in Hillman Library by using cash or a major credit credit car; or by calling the Panther Central office (412-648-1100) or visiting Panther Central in the lobby of Litchfield Towers and using cash or a major credit card. -

ISSN 0022-2224 August 2016 Published Continuously Since 1967

the journal of visual communication research special issue: reecting of 50 years of Typography Charles Bigelow and Kevin Larson Guest Editors 50 .2 ISSN 0022-2224 august 2016 Published continuously since 1967. Visible Language the journal of visual communication research special issue: Relecting on 50 years of Typography Charles Bigelow and Kevin Larson Guest Editors August 2016 Visible Language 50.2 Contents The Xerox Alto Font Design System Patrick Baudelaire 12 — 25 The Digital Typefoundry Matthew Carter 26 — 37 Advisory Board Naomi Baron – The American University, Washington, D.C. two letters: 1968 & 2016 Michael Bierut – Pentagram, New York, NY Charles Bigelow – Type designer Schmoller & Matteson Matthew Carter – Carter & Cone Type, Cambridge, MA 38 — 39 Keith Crutcher – Cincinnati, OH Mary Dyson – University of Reading, UK Jorge Frascara – University of Alberta, Canada / Universidad de las Americas Puebla Ken Friedman – Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia Communication of Mathematics with TEX Michael Golec – School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL Barbara Beeton, Richard Palais Judith Gregory – University of California-Irvine, Irvine, CA Kevin Larson – Microsoft Advanced Reading Technologies 40 — 51 Aaron Marcus – Aaron Marcus & Associates, Berkeley, CA Per Mollerup – Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia Commercial at @ Tom Ockerse – Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI Sharon Poggenpohl – Estes Park, CO James Mosley Michael Renner – The Basel School of Design – Visual Communication Institute, 52 — 63 Academy of Art and Design, HGK FHNW Stan Ruecker – IIT, Chicago, IL Katie Salen – DePaul University, Chicago, IL Letterform Research: an academic orphan Peter Storkerson – Champaign, IL Karl van der Waarde – Avans University, Breda, The Netherlands Soie Beier Mike Zender – University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 64 — 79 2 3 Visible Language special issue: Typography 50.2 Orthographic Processing and Reading Jonathan Grainger 80 — 101 Reading Digital with Low Vision Gordon E. -

The Sensualistic Philosophy of the Nineteenth Century

THE SENSUALISTIC PHILOSOPHY THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, CONSIDERED ROBERT L. DABNEY, D.D., LL.D., PROFESSOR IN DIVINITY IN THE UNION THEOLOGICA\. SEMINARY, OF THE PRESBYTER1AH CHURCH OF THB SOUTH PRINCE EDWARD, VA. EDINBURGHl T. & T. CLARK, 38 GEORGE STREET. 1876. CONTENTS. CHAPTER. PAGE. I. THE ISSUE STATED, i II. REVIEW OF THE SENSUALISTIC PHILOSOPHY OF THE PREVIOUS CENTURY. HOBBES, LOCKE, CONDIL- LAC, HELVETIUS, ST. LAMBERT, ... 7 III. ANALYSIS OF THE HUMAN MIND, . .52 IV. SENSUALISTIC ETHICS OF GREAT BRITAIN, . 85 V. POSITIVISM, 93 VI. EVOLUTION THEORY, 107 VII. PHYSIOLOGICAL MATERIALISM, . -131 VIII. SPIRITUALITY OF THE MIND, .... 137 IX. EVOLUTION THEORY MATERIALISTIC, THEREFORE FALSE, 165 X. VALIDITY OF A-PRIORI NOTIONS, . 208 XI. ORIGIIJ OF A-PRIORI NOTIONS, . 245 XII. REFUTATION OF SENSUALISTIC ETHICS, . 287 XIII. PHILOSOPHY OF THE SUPERNATURAL, . 337 .13.15892 SENSUALISTIC PHILOSOPHY. CHAPTER I. THE ISSUE STATED. TT^NGLISHMEN and Americans frequently use the ^ word "sensualist" to describe one in whom the animal appetites are predominant. We shall see that it is a just charge against the Sensualistic philosophy, that it not seldom inclines its advocates to this dominion of beastly lusts. But it is not from this fact that we draw the phrase by which we name it. The Sensualistic philosophy is that theory, which resolves all the powers of the human spirit into the functions of the five senses, and modifications thereof. It is the philosophy which finds all its rudiments in sensation. It not only denies to the spirit of man all innate ideas, but all innate powers of originating ideas, save those given us from our senses. -

The English Renaissance in Context: Looking at Older Books

The English Renaissance in Context: Looking at Older Books The History of the Book Books from the 16th and 17th centuries are both quite similar to and different from books today. The similarities include such things as use of the Codex format, general page layouts, use of title pages, etc. The codex book has been around for a long time. Its roots go back to the age of Cicero, though it only comes into more general use with the spread of Christianity throughout the later Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries CE. Since then, the codex book has undergone a long and gradual evolution during which time the book, its properties, and characteristics became firmly embedded in Western consciousness. Roughly speaking, the general layout of the page that we use today came into existence in the 13th century, with the rise of the universities and the creation of books for study. It is possible, for example, to look at a page in a medieval manuscript and experience a general orientation to it, even if you cannot actually read the text. The evolution of the book, we emphasize, was slow. Such conventions as pagination, title pages, foot or endnotes, tables of contents, indices, et alia are by and large relatively recent additions. We take these features for granted; but prior to the age of Gutenberg, they are hard to find. University of Pennsylvania Libraries - 1 - Furness Shakespeare Collection The English Renaissance in Context: Looking at Older Books Renaissance books can certainly look very different from books today. They exhibit a variety and diversity that have long since been standardized and homogenized. -

Typographic Design: Form and Communication

Typographic Design: Form and Communication Fifth Edition Saint Barbara. Polychromed walnut sculpture, fifteenth- century German or French. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Typographic Design: Form and Communication Fifth Edition Rob Carter Ben Day Philip Meggs JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2012 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750- 8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or on-line at www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. -

566,581 Sept. 4, 1951

Sept. 4, 1951 W. PETERSON 2 566,581 STEREOTYPE CASTING MACHINE Original Filed March ill, 1948 Z2222227 2e A222s22. 3-2 22.2%v1. Patented Sept. 4, 1951 2,566,581 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE 2,566,581 sTEREOTYPE CASTING MACHINE Wayne Peterson, Moorhead, Minn. Continuation of application Serial No. 14262, March 11, 1948. This application April 28, 1950, Serial No. 158,747 1 Claim. (C. 22-3) My invention relates generally to stereotype cated at 8) is an elongated metal box or melting casting machines, and, more Specifically, to a pot 9, which has upwardly-diverging sides O. A stereotype casting machine scorcher combina tilting lever is secured fast to the metal box 9 tion. The present application is a continuation through one of the pivot connections 8 for tilting of application Serial No. 14262, filed March 11, the metal pot 9 when it is desired to pour through 1948, now abandoned. a Suitable pouring spout 2. formed in the rear The primary object of my invention is the pro wall. Othereof. It will be observed that the pivot vision of a novel arrangement, including casting connections 8 are located to one side of the platens, metal pot, heater, and scorcher, wherein longitudinal center of the metal box 9. A front the heat utilized to melt type metal in the mettal 0. Wall 0 of the metal box is provided with a for port is also utilized for heating the Scorcher Wardly-projecting flange 3, which is adapted to platen. normally rest upon a Supporting bracket 4 con Another object of my invention is the provision necting its opposite ends to forward edges of the of a novel scorcher having relatively fixed and upStanding flanges 7.