General Assembly GENERAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINAL REPORT: Evaluation of the Local Governance and Infrastructure Program

FINAL REPORT: Evaluation of the Local Governance and Infrastructure Program An evaluation of the effect of LGI's local government initiatives on institutional development and participatory governance Pablo Beramendi, Soomin Oh, Erik Wibbels July 24, 2018 AAID Research LabDATA at William & Mary Author Information Pablo Beramendi Professor of Political Science and DevLab@Duke Soomin Oh PhD Student and DevLab@Duke Erik Wibbels Professor of Political Science and DevLab@Duke The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be attributed to AidData or funders of AidData’s work, nor do they necessarily reflect the views of any of the many institutions or individuals acknowledged here. Citation Beramendi, P., Soomin, O, & Wibbels, E. (2018). LGI Final Report. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary. Acknowledgments This evaluation was funded by USAID/West Bank and Gaza through a buy-in to a cooperative agreement (AID-OAA-A-12-00096) between USAID's Global Development Lab and AidData at the College of William and Mary under the Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) Program. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Tayseer Edeas, Reem Jafari, and their colleagues at USAID/West Bank and Gaza, and of Manal Warrad, Safa Noreen, Samar Ala' El-Deen, and all of the excellent people at Jerusalem Media and Communication Centre. Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 1.1 Key Findings . .1 1.2 Policy Recommendations . .2 2 Introduction 3 3 Background 4 4 Research design 5 4.1 Matching . .6 4.1.1 Survey Design and Sampling . .8 4.1.2 World Bank/USAID LPGA Surveys . -

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 05-20-2009 I, Shadi Y. Saleh , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master in Architecture It is entitled: Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps Shadi Saleh Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Elizabeth Riorden Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advance Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Architecture In the school of Architecture and Interior design Of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning 2009 By Shadi Y. Saleh Committee chair Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible ABSTRACT Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria are the result of the sudden population displacements of 1948 and 1967. After 60 years, unorganized urban growth compounds the situation. The absence of state support pushed the refugees to take matters into their own hands. Currently the camps have problems stemming from both the social situation and the degradation of the built environment. Keeping the refugee camps in order to “represent” a nation in exile does not mean to me that there should be no development. The thesis seeks to make a contribution in solving the social and environmental problems in a way that emphasizes the Right of Return. -

اﻟ ﻣرآزاﻟ ﻔ ﻟ ﺳط ﯾ ﻧ ﯾ ﻟﺣ ﻘوﻗ ﺎﻹﻧ ﺳﺎن PALESTINIAN CENTRE for HUMAN RIGHTS the Dead I

ال مرآزال ف ل سط ي ن ي لح قوق اﻹن سان PALESTINIAN CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS The Dead in the course of the Israeli recent military offensive on the Gaza strip between 27 December 2008 and 18January 2009 17 years old and belowWomen # Name Sex Ag Occupation Address Date of Date of Place of Attack Governor Civilian/ e death attack ate milit ant 1 Mustafa Khader Male 16 Student Tal al-Hawa / Gaza 27-Dec-08 27-Dec-08 Tal al- Gaza Civilian Saber Abu Ghanima Hawa/Gaza 2 Reziq Jamal Reziq al- Male 21 Policeman al-Sha'af / Gaza 27-Dec-08 27-Dec-08 Arafat Police Gaza Civilian Haddad City/Gaza 3 Ali Mohammed Jamil Male 24 Policeman Al-Shati Refugee 27-Dec-08 27-Dec-08 Arafat Police Gaza Civilian Abu Riala Camp / Gaza City/Gaza 4 Ahmed Mohammed Male 27 Policeman Al-Shati Refugee 27-Dec-08 27-Dec-08 Al- Gaza Civilian Ahmed Badawi Camp / Gaza MashtalIntellige nceOutpost/ Gaza 5 Mahmoud Khalil Male 31 Policeman Martyr Bassil Naim 27-Dec-08 27-Dec-08 Al-Mashtal Gaza Civilian Hassan Abu Harbeed Street/ Beit Hanoun Intelligence Outpost/ Gaza 6 Fadia Jaber Jabr Female 22 Student Al-Tufah / Gaza 27-Dec-08 27-Dec-08 Al-Tufah / Gaza Gaza Civilian Hweij 7 Mohammed Jaber Male 19 Student Al-Tufah / Gaza 27-Dec-08 27-Dec-08 Al-Tufah / Gaza Gaza Civilian JabrHweij 8 Nu'aman Fadel Male 56 Jobless Al-Zaytoon / Gaza 27-Dec-08 27-Dec-08 Tal al-Hawa / Gaza Civilian Salman Hejji Gaza 9 Riyad Omar Murjan Male 24 Student Yarmouk Street / Gaza 27-Dec-08 27-Dec-08 Al-Sena’a Street Gaza Civilian Radi / Gaza 10 Mumtaz Mohammed Male 37 Policeman Al-Sabra/ Gaza 27-Dec-08 27-Dec-08 -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

Terminals, Agricultural Crossings and Gates

Terminals, Agricultural Crossings and Gates Umm Dar Terminals ’AkkabaDhaher al ’Abed Zabda Agricultural Gate (gap in the Wall) Controlled access through the Wall has been promised by the GOI to Ya’bad Wall (being finalised or complete) Masqufet al Hajj Mas’ud enable movement between Israel and the West Bank for Palestinian West Bank boundary/Green Line (estimate) Qaffin Imreiha populations who are either trapped in enclaves or isolated from their Road network agricultural lands. Palestinian Locality Hermesh Israeli Settlement Nazlat ’Isa An Nazla al Wusta According to Israel's State Attorney's office, five controlled crossings or NOTE: Agricultural Gate locations have been Baqa ash Sharqiya collected from field visits by OCHA staff and An Nazla ash Sharqiya terminals similar to the Erez terminal in northern Gaza will be built along information partners. The Wall trajectory is based on satellite imagery and field visits. An Nazla al Gharbiya the Wall. The Government of Israel recently decided that the Israeli Airport Authority will plan and operate the terminals. One of the main terminals between Israel and the West Bank appears to be being built Zeita Seida near Taibeh, 75 acres (300 dunums)35 in a part of Tulkarm City 36 Kafr Ra’i considered area A. ’Attil ’Illar The remaining terminals/control points are designated for areas near Jenin, Atarot north of Jerusalem, north of the Gush Etzion and near Deir al Ghusun Tarkumiyeh settlement bloc. Al Jarushiya Bal’a Agricultural Crossings and Gates Iktaba Al ’Attara The State Attorney's Office has stated that 26 agricultural gates will be TulkarmNur Shams Camp established along the length of the Wall to allow Palestinian farmers who Kafr Rumman have land west of the Wall, to cross. -

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

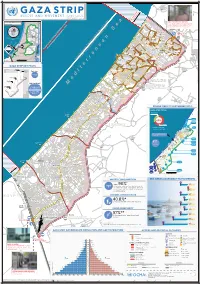

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

The Earless Children of the Stone

REFUGEE PARTICIPATION NETWORK 7 nvxi February 1990 Published by Refugee Studies Programme, Queen Elizabeth House, 21 St Giles, OXFORD OX1 3LA, UK. THE EARLESS CHILDREN OF THE STONE ££££ ;0Uli: lil Sr«iiKKiJi3'^?liU^iQ^^:;fv'-' » <y * C''l* I WW 'tli' (Cbl UUrHfill'i $ J ?ttoiy#j illCiXSa * •Illl •l A Palestinian Mother of Fifteen Children: 7 nave fen sons, eacn wi// nave ten more so one hundred will throw stones' * No copyright. MENTAL HEALTH CONTENTS THE INTIFADA: SOME PSYCHOLOGICAL Mental Health 2 CONSEQUENCES * The Intifada: Some Psychological Consequences * The Fearless Children of the Stone The End of Ramadan * Testimony and Psychotherapy: a Reply to Buus and Agger riday was a busy day in the town of Gaza, with many people F out in the streets buying food in preparation for the celebration ending Ramadan. The unified Leadership of Palestine Refugee Voices from Indochina 8 had issued a clandestine decree that shops could stay open until 5 * Forced or Voluntary Repatriation? p.m., and that people should stay calm during the day of the feast. * What is it Like to be a Refugee in They were not to throw stones at the soldiers while Site 2 Refugee Camp on the demonstrating. On their side, the Israeli authorities were said to have promised to keep their soldiers away from the refugee Thai-Cambodian Border? camps. Later, the matron of Al Ahli Arab general hospital * Some Conversations from Site 2 confessed that she had nonetheless kept her staff on full alert. Camp * Return to Vietnam In the early morning of Saturday, 6 May we awoke to cracks of gunfire and the rumble of low flying helicopters. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Report: T I O 21N MarchS – 27 March 2007 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 21 March – 27 March 2007 Of note this week Five Palestinians, including three children, were killed and more than 35 injured when sand barriers of a wastewater collection pool collapsed flooding the nearby Bedouin Village and al Nasser area in the northern Gaza Strip with sewage water. Extensive property damage and destruction resulted and a temporary relief camp was sheltering approximately 1,450 people. West Bank: − The PA health sector strike continues for more than one month in the West Bank. Employees of the health sector staged a sit-in in front of Alia Governmental Hospital in Hebron to protest the government’s inability to pay employees’ salaries. In Bethlehem, all municipality workers went on a one-day strike to protest non-payment of their salaries over the past four months. − Clashes at Qalandiya checkpoint (Jerusalem) have occurred on a regular basis on Friday afternoons following the construction work by Israel at the Mughrabi gate in the Old City area. This week, Palestinians threw Molotov cocktails and stones at IDF soldiers who responded with live rounds injuring one Palestinian. Gaza Strip − 18 homemade rockets, three of which detonated in a Palestinian area, and a Rocket Propelled Grenade (RPG) were fired at an IDF observation post east of Al Maghazi Camp. -

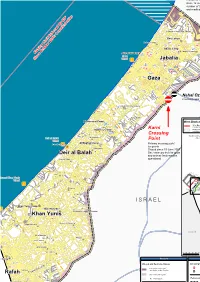

Gaza Strip Closure Map , December 2007

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Access and Closure - Gaza Strip December 2007 s rd t: o i t c im n N c L e o Erez A . m F g m t i lo n . i s s i n m h Crossing Point h t: in O s 0 m i s g i 2 o le F im i A Primary crossing for people (workers C L m re i l a and traders) and humanitarian personnel in g a rt in c Closed for Palestinian workers e h ti s u since 12 March 2006 B i a 2 F Closed for Palestinians 0 n 0 2 since 12 June 2007 except for a limited 2 1 number of traders, humanitarian workers and medical cases s F le D i I m y l B a d ic e t c u r a Al Qaraya al Badawiya al Maslakh ¯p fo n P Ç 6 n : ¬ E 6 it 0 Beit Lahiya 0 im 2 P L r Madinat al 'Awda e P ¯p "p ¯p "p g b Beit Hanoun in o ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p h t Jabalia Camp ¯p ¯p ¯p P ¯p s c p ¯p ¯p i p"p ¯¯p "pP 'Izbat Beit HanounP F O Ash Shati' Camp ¯p " ¯p e "p "p ¯p ¯p c Gaza ¯Pp ¯p "p n p i t ¯ Wharf S Jabalia S t !x id ¯p S h s a a "p m R ¯p¯p¯p ¯p a l- ¯p p r A ¯p ¯ a "p K "p ¯p l- ¯p "p E ¯p"p ¯p¯p"p ¯p¯p ¯p Gaza ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p t S ¯p a m ¯p¯p ¯p ra a K l- Ç A ¬ Nahal Oz ¯p ¬Ç Crossing point for solid and liquid fuels p t ¯ t S fa ¯p Al Mughraqa (Abu Middein) ra P r A e as Y Juhor ad Dik ¯pP ¯p LEBANON An Nuseirat Camp ¯p ¯p West Bank and Gaza Strip P¯p ¯p ¯p West Bank Barrier (constructed and planned) ¯p ¯p ¯p Al Bureij Camp¯p ¯p Karni Areas inaccessible to Palestinians or subject to restrictions ¯p¯pP¯p Crossing `Akko !P MEDITERRANEAN Az Zawayda !P Deir al Balah ¯p P Point SEA Haifa Tiberias !P Wharf Nazareth !P ¯p Al Maghazi Camp¯p¯p Deir al Balah Camp Primary -

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

(^Ш/ World Health Organization ^^^^ Organisation Mondiale De La Santé

(^Ш/ World Health Organization ^^^^ Organisation mondiale de la Santé FORTY-SEVENTH WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY Provisional agenda item 32 A47/INF.DOC./3 2 May 1994 Health conditions of the Arab population in the occupied Arab territories, including Palestine The Director-General has the honour to bring to the attention of the Health Assembly the attached annual report of the Director of Health of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) for the year 1993. HEALTH CONDITIONS OF THE ARAB POPULATION IN THE OCCUPIED ARAB TERRITORIES, INCLUDING PALESTINE Report of the UNRWA Department of Health, 1993 CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 2 II. UNRWA'S HEALTH PROGRAMME 2 III. HEALTH STATUS OF PALESTINE REFUGEES 3 IV. PROGRAMME ACTIVITIES DURING 1993 5 Medical Care Services 5 Maternal and Child Health Care 5 Mental Health 6 Environmental Health 6 V. SITUATION IN THE OCCUPIED TERRITORY 8 VI. UNRWA'S CONTRIBUTION TO HEALTH SECTOR DEVELOPMENT 8 VII. UNRWA'S ROLE DURING THE TRANSITION PERIOD 10 STATISTICAL ANNEX 13 I. INTRODUCTION 1. The Annual Report of the Department of Health of UNRWA for 1993 covers a year in which historic events have taken place that will create a radically different situation in the Agency's area of operations. 2. The Palestine Liberation Organization and the Government of Israel have recognized each other and signed a Declaration of Principles, which is guiding their negotiations for an interim self-government period in the Gaza Strip and West Bank. 3. There is no doubt that these momentous developments have already had a great impact on the perceptions of all parties concerned as well as on UNRWA's role under the new conditions.