The Beginnings of Deaf Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Sasl) in a Bilingual-Bicultural Approach in Education of the Deaf

APPLICATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN SIGN LANGUAGE (SASL) IN A BILINGUAL-BICULTURAL APPROACH IN EDUCATION OF THE DEAF Philemon Abiud Okinyi Akach August 2010 APPLICATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN SIGN LANGUAGE (SASL) IN A BILINGUAL-BICULTURAL APPROACH IN EDUCATION OF THE DEAF By Philemon Abiud Omondi Akach Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR in the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES (DEPARTMENT OF AFROASIATIC STUDIES, SIGN LANGUAGE AND LANGUAGE PRACTICE) at the UNIVERSITY OF FREE STATE Promoter: Dr. Annalie Lotriet. Co-promoter: Dr. Debra Aarons. August 2010 Declaration I declare that this thesis, which is submitted to the University of Free State for the degree Philosophiae Doctor, is my own independent work and has not previously been submitted by me to another university or faculty. I hereby cede the copyright of the thesis to the University of Free State Philemon A.O. Akach. Date. To the deaf children of the continent of Africa; may you grow up using the mother tongue you don’t acquire from your mother? Acknowledgements I would like to say thank you to the University of the Free State for opening its doors to a doubly marginalized language; South African Sign Language to develop and grow not only an academic subject but as the fastest growing language learning area. Many thanks to my supervisors Dr. A. Lotriet and Dr. D. Aarons for guiding me throughout this study. My colleagues in the department of Afroasiatic Studies, Sign Language and Language Practice for their support. Thanks to my wife Wilkister Aluoch and children Sophie, Susan, Sylvia and Samuel for affording me space to be able to spend time on this study. -

Deaf-History-Part-1

[from The HeART of Deaf Culture: Literary and Artistic Expressions of Deafhood by Karen Christie and Patti Durr, 2012] The Chain of Remembered Gratitude: The Heritage and History of the DEAF-WORLD in the United States PART ONE Note: The names of Deaf individuals appear in bold italics throughout this chapter. In addition, names of Deaf and Hearing historical figures appearing in blue are briefly described in "Who's Who" which can be accessed via the Overview Section of this Project (for English text) or the Timeline Section (for ASL). "The history of the Deaf is no longer only that of their education or of their hearing teachers. It is the history of Deaf people in its long march, with its hopes, its sufferings, its joys, its angers, its defeats and its victories." Bernard Truffaut (1993) Honor Thy Deaf History © Nancy Rourke 2011 Introduction The history of the DEAF-WORLD is one that has constantly had to counter the falsehood that has been attributed to Aristotle that "Those who are born deaf all become senseless and incapable of reason."1 Our long march to prove that being Deaf is all right and that natural signed languages are equal to spoken languages has been well documented in Deaf people's literary and artistic expressions. The 1999 World Federation of the Deaf Conference in Sydney, Australia, opened with the "Blue Ribbon Ceremony" in which various people from the global Deaf community stated, in part: "...We celebrate our proud history, our arts, and our cultures... we celebrate our survival...And today, let us remember that many of us and our ancestors have suffered at the hands of those who believe we should not be here. -

Deaf American Historiography, Past, Present, and Future

CRITICAL DISABILITY DISCOURSES/ 109 DISCOURS CRITIQUES DANS LE CHAMP DU HANDICAP 7 The Story of Mr. And Mrs. Deaf: Deaf American Historiography, Past, Present, and Future Haley Gienow-McConnella aDepartment of History, York University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a review of deaf American historiography, and proposes that future scholarship would benefit from a synthesis of historical biography and critical analysis. In recent deaf historical scholarship there exists a tendency to privilege the study of the Deaf community and deaf institutions as a whole over the study of the individuals who comprise the community and populate the institutions. This paper argues that the inclusion of diverse deaf figures is an essential component to the future of deaf history. However, historians should not lapse in to straight-forward biography in the vein of their eighteenth and nineteenth-century predecessors. They must use these stories purposefully to advance larger discussions about the history of the deaf and of the United States. The Deaf community has never been monolithic, and in order to fully realize ‘deaf’ as a useful category of historical analysis, the definition of which deaf stories are worth telling must broaden. Biography, when coupled with critical historical analysis, can enrich and diversify deaf American historiography. Key Words Deaf history; historiography; disability history; biography; American; identity. THE STORY OF MR. AND MRS. DEAF 110 L'histoire de «M et Mme Sourde »: l'historiographie des personnes Sourdes dans le passé, le présent et l'avenir Résumé Le présent article offre un résumé de l'historiographie de la surdité aux États-Unis, et propose que dans le futur, la recherche bénéficierait d'une synthèse de la biographie historique et d’une analyse critique. -

Laurent Clerc, His Uncle and Godfather, Stepped in When He Was 12

Laurent(1785-1869) Clerc Early Life ● A fire permanently changed the course of Laurent's life when he was only one year old. ● He was born to a comfortable situation in France, he fell off of his high chair into the kitchen fire and was badly burned. ● It is believed that this accident and the subsequent fever were the source of his lifelong deafness and lost sense of smell. ● Despite the efforts by his parents to reverse his condition, Laurent was suddenly left with fewer prospects. ● Laurent received no official schooling until another Laurent Clerc, his uncle and godfather, stepped in when he was 12. ● Once Laurent was enrolled in the Institut National des Jeune Sourds-Muets, a school for the Deaf in France. ● His life then took a turn for the better. Early life (continued) ● Laurent caught up quickly on his education, eventually becoming a beloved teacher at the institute. ● It was during this time that he crossed paths with Thomas Gallaudet in London and Laurent’s life was forever changed once again. ● Gallaudet, future co-founder of the first school for the Deaf in America, visited Laurent in France and was impressed with his teaching methods. ● Gallaudet asked Laurent to be a part of his plans to educate the Deaf in the United States, and he agreed to join the venture. Laurent’s Work in America ● Laurent left his homeland and immediately begin applying his skills by teaching Gallaudet sign language on the journey from France to America. ● Once on American soil, Laurent worked with Gallaudet and others to raise funds for the new school; speaking, fundraising and rounding up future The Laurent Clerc, students. -

21. Bibliografía

BIBLIOGRAFÍA1121 A) Material impreso y/o digitalizado Abergel, R. (s. d.): L’enfant sourd et la psychomôtricite. Hommage à Pereire. Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du Certificat de capacité d‘orthophoniste (Memoria no publicada pre- sentada para la obtención del certificado de capacidad de ortofonista. Universidad Louis Pasteur. Facultad de Medicina. Strasbourg). Acquier, Marie-Laure (2000): «Los Tratados en prosa de Antonio López de Vega: aproxima- ción al discurso político en el siglo XVII», Cuadernos de Historia Moderna, n.º 24, 11-31, pp. 85-106. Aftonio, Elio Festo (1961): De metris, en H. Keil (ed.): Grammatici Latini, vol. VI, Hildes- heim, Olms; reimpr de la. 1.ª ed. de Leipzig, 1874, pp. 31-173. Aguado Díaz, A. L. (1995): Historia de las Deficiencias, Madrid, Escuela Libre Editorial (Col. Tesis y Praxis). Aguirre Lora, G. M. E. (dir./1993): Juan Amós Comenio: obra, andanzas, atmosferas en el IV centenario de su nacimiento. (1592-1992), Coyoacán, Centro de Estudios sobre la Universidad. Agulló y Cobo, Mercedes (1992): La imprenta y el comercio de libros en Madrid (siglos XVI- XVIII), Madrid, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Ainscow, M. (2001): Desarrollo de escuelas inclusivas. Ideas propuestas y experiencias para mejorar las instituciones escolares, Madrid, Narcea. Alcuino de York (1851): Grammatica, en Frobenius (ed.): Opera omnia, en J.-P. Migne: Patro- logia Latina, vol. CI, Turnholti, Brepols, reimpr.de la 1.ª ed. de París, 1777, cols. 849-902. Aldea Vaquero, Quintín de (1986): España y Europa en el siglo XVII. Correspondencia de Saavedra Faxardo. 1631-1633, Madrid, CSIC. Alemán, Mateo (1609): Ortografía castellana, México, Jerónimo Balli. -

The Two Hundred Years' War in Deaf Education

THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS' WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy By A. Tellings PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/146075 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2020-04-15 and may be subject to change. THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS* WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy By A. Tellings THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS' WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy EEN WETENSCHAPPELIJKE PROEVE OP HET GEBIED VAN DE SOCIALE WETENSCHAPPEN PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR AAN DE KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT NIJMEGEN, VOLGENS BESLUIT VAN HET COLLEGE VAN DECANEN IN HET OPENBAAR TE VERDEDIGEN OP 5 DECEMBER 1995 DES NAMIDDAGS TE 3.30 UUR PRECIES DOOR AGNES ELIZABETH JACOBA MARIA TELLINGS GEBOREN OP 9 APRIL 1954 TE ROOSENDAAL Dit onderzoek werd verricht met behulp van subsidie van de voormalige Stichting Pedon, NWO Mediagroep Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen PROMOTOR: Prof.Dr. A.W. van Haaften COPROMOTOR: Dr. G.L.M. Snik 1 PREFACE The methods controversy in deaf education has fascinated me since I visited the International Congress on Education of the Deaf in Hamburg (Germany) in 1980. There I was struck by the intemperate emotions by which the methods controversy is attended. This book is an attempt to understand what this controversy really is about I would like to thank first and foremost Prof.Wouter van Haaften and Dr. -

Books About Deaf Culture

Info to Go Books about Deaf Culture 1 Books about Deaf Culture The printing of this publication was supported by federal funding. This publication shall not imply approval or acceptance by the U.S. Department of Education of the findings, conclusions, or recommendations herein. Gallaudet University is an equal opportunity employer/educational institution, and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, national origin, religion, age, hearing status, disability, covered veteran status, marital status, personal appearance, sexual orientation, family responsibilities, matriculation, political affiliation, source of income, place of business or residence, pregnancy, childbirth, or any other unlawful basis. 2 Books about Deaf Culture There are many books about the culture, language, and experiences that bind deaf people together. A selection is listed in alphabetical order below. Each entry includes a citation and a brief description of the book. The names of deaf authors appear in boldface type. Abrams, C. (1996). The silents. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. A hearing daughter portrays growing up in a close Jewish family with deaf parents during the Depression and World War II. When her mother begins to also lose her sight, the family and community join in the effort to help both parents remain vital and contributing members. 272 pages. Albronda, M. (1980). Douglas Tilden: Portrait of a deaf sculptor. Silver Spring, MD: T. J. Publishers. This biography portrays the artistic talent of this California-born deaf sculptor. Includes 59 photographs and illustrations. 144 pages. Axelrod, C. (2006). And the journey begins. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. Cyril Axelrod was born into an Orthodox Jewish family and is now deaf and blind. -

Variation and Change in English Varieties of British Sign Languagei

Variation and change in English varieties of BSL 1 Variation and change in English varieties of British Sign Languagei Adam Schembri, Rose Stamp, Jordan Fenlon and Kearsy Cormier British Sign Language (BSL) is the language used by the deaf community in the United Kingdom. In this chapter, we describe sociolinguistic variation and change in BSL varieties in England. This will show how factors that drive sociolinguistic variation and change in both spoken and signed language communities are broadly similar. Social factors include, for example, a signer’s age group, region of origin, gender, ethnicity, and socio-economic status (e.g., Lucas, Valli & Bayley 2001). Linguistic factors include assimilation and co-articulation effects (e.g., Schembri et al. 2009; Fenlon et al. 2013). It should be noted, however, some factors involved in sociolinguistic variation in sign languages are distinctive. For example, phonological variation includes features, such as whether a sign is produced with one or two hands, which have no direct parallel in spoken language phonology. In addition, deaf signing communities are invariably minority communities embedded within larger majority communities whose languages are in another entirely different modality and which may have written systems, unlike sign languages. Some of the linguistic outcomes of this contact situation (such as the use of individual signs for letters to spell out written words on the hands, known as fingerspelling) are unique to such communities (Lucas & Valli 1992). This picture is further complicated by patterns of language transmission which see many deaf individuals acquiring sign languages as first languages at a much later age than hearing individuals (e.g., Cormier et al. -

Lessons from the LEAD-K Campaign for Language Equality for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Loyola University Chicago, School of Law: LAW eCommons Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 51 Issue 1 Fall 2019 Article 6 2019 Lessons from the LEAD-K Campaign for Language Equality for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children Christina Payne-Tsoupros Follow this and additional works at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Christina Payne-Tsoupros, Lessons from the LEAD-K Campaign for Language Equality for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children, 51 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 107 (). Available at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol51/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized editor of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lessons from the LEAD-K Campaign for Language Equality for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children Christina Payne-Tsoupros* ABSTRACT This Article asserts that early intervention under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (IDEIA) should be amended to recognize the needs of the young child with the disability as primary over the needs of the child’s family. This Article contends that certain requirements of the IDEIA cause early intervention professionals to view and treat the child’s family, rather than the child herself, as the ultimate recipient of support. In many situations, the needs of the family and the needs of the child may wholly align, but that is an assumption that bears questioning. -

Boognl,Emily the Development of ASL Copy

22222 The Development of American Sign Language Emily Boognl Junior Division Paper Paper: 2,393 words Process Paper: 323 words 22222 Process Paper I chose my topic because in my last year of elementary school one of my teachers had an American Sign Language dictionary, and some of my friends and I were very interested in it and wanted to learn bits and pieces of ASL. The development of ASL relates to the annual theme of communication because ASL is how people who are deaf communicate with each other along with those that are hearing. I conducted my research by going to the internet, and I found some helpful evidence to support my side of the story. I also tried to find an argumentative side to my opinion when I did my research. I went to the public library and got a book about ASL that I used to do some of my research. One of my most important resources was Mrs. Karol McGregor, who is apart of the deaf community and deals with deafness everyday. When I created my project I really just did my research and then started to write. For me it is easiest to write down the important facts and then move them around and place them where they needed to be. My historical argument is that learning sign language and being able to speak sign is very important. Being able to speak sign language is a life skill for not only people who are deaf, but for those that want to be all inclusive to any person whether they are hearing or deaf. -

Deaf History Notes Unit 1.Pdf

Deaf History Notes by Brian Cerney, Ph.D. 2 Deaf History Notes Table of Contents 5 Preface 6 UNIT ONE - The Origins of American Sign Language 8 Section 1: Communication & Language 8 Communication 9 The Four Components of Communication 11 Modes of Expressing and Perceiving Communication 13 Language Versus Communication 14 The Three Language Channels 14 Multiple Language Encoding Systems 15 Identifying Communication as Language – The Case for ASL 16 ASL is Not a Universal Language 18 Section 2: Deaf Education & Language Stability 18 Pedro Ponce DeLeón and Private Education for Deaf Children 19 Abbé de l'Epée and Public Education for Deaf Children 20 Abbé Sicard and Jean Massieu 21 Laurent Clerc and Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet 23 Martha's Vineyard 24 The Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons 27 Unit One Summary & Review Questions 30 Unit One Bibliography & Suggested Readings 32 UNIT TWO - Manualism & the Fight for Self-Empowerment 34 Section 1: Language, Culture & Oppression 34 Language and Culture 35 The Power of Labels 35 Internalized Oppression 37 Section 2: Manualism Versus Oralism 37 The New England Gallaudet Association 37 The American Annals of the Deaf 38 Edward Miner Gallaudet, the Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, and the National Deaf-Mute College 39 Alexander Graham Bell and the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf 40 The National Association of the Deaf 42 The International Convention of Instructors of the Deaf in Milan, Italy 44 -

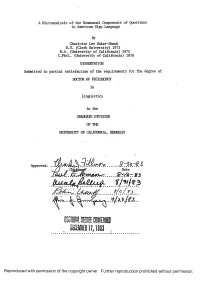

Iffls G E M M E U . IW EB17J8S3

A M icroanalysis o f the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language By Charlotte Lee Baker-Shenk B.S. (Clark U niversity) 1972 M.A. O Jniversity o f C alifornia) 1975 C.Phil. (University of California) 1978 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Approved: Date IfflSGEMMEU . IWEB17J8S3 \ Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. A Microanalysis of the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language C opyright © 1983 by Charlotte Lee Baker-Shenk Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements .................................................................................. v ii List of Figures .................................................................................... x List of Photographs ..................................... x ii List of Drawings .......................................................................................x i i i Transcription Conventions .................................................... iv C hapter I - EXPERIENCES OF DEAF PEOPLE IN A HEARING WORLD ................................................. 1 1.0 Formal education of deaf people: historical review •• 1 1.1