The Landmark Trust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mauchline CARS

Potential Mauchline CARS Public Meeting Venue: Centre Stane, Mauchline 7pm Monday 5th November 2018 Colin McKee - Heritage Projects Coordinator Mauchline CARS What is a Conservation Area Regeneration Scheme(CARS)? A five year Historic Environment Scotland programme that can offer grant of up to £2 million to support cohesive heritage-focused community and economic growth projects within Conservation Areas across Scotland. The grant scheme would be jointly funded by East Ayrshire Council and Historic Environment Scotland, with any additional external funding that can be secured for specific projects. CARS Overview Historic Environment Scotland Expect CARS to Deliver:- • A combination of larger building repair projects, • Small third-party grant schemes providing funding for repairs to properties in private ownership, • Activities which promote community engagement with the local heritage and; • Training for professionals and tradespeople in traditional building skills, All of which will contribute to sustainable economic and community development within the Conservation Area. HES Criteria for Awarding a CARS • CARS bids are assessed in competition with each other. • HES assess how well the project achieves the priority outcomes for the CARS programme • How well planned and deliverable it is • How we plan to sustain the scheme benefits in the longer term. HES Priority Outcomes The four CARS priority outcomes are listed below:- Understand • Priority outcome: Communities are empowered to take an active role in understanding and enhancing -

Ayrshire & the Isles of Arran & Cumbrae

2017-18 EXPLORE ayrshire & the isles of arran & cumbrae visitscotland.com WELCOME TO ayrshire & the isles of arran and cumbrae 1 Welcome to… Contents 2 Ayrshire and ayrshire island treasures & the isles of 4 Rich history 6 Outdoor wonders arran & 8 Cultural hotspots 10 Great days out cumbrae 12 Local flavours 14 Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology 2017 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips 20 VisitScotland iCentres 21 Quality assurance 22 Practical information 24 Places to visit listings 48 Display adverts 32 Leisure activities listings 36 Shopping listings Lochranza Castle, Isle of Arran 55 Display adverts 37 Food & drink listings Step into Ayrshire & the Isles of Arran and Cumbrae and you will take a 56 Display adverts magical ride into a region with all things that make Scotland so special. 40 Tours listings History springs to life round every corner, ancient castles cling to spectacular cliffs, and the rugged islands of Arran and Cumbrae 41 Transport listings promise unforgettable adventure. Tee off 57 Display adverts on some of the most renowned courses 41 Family fun listings in the world, sample delicious local food 42 Accommodation listings and drink, and don’t miss out on throwing 59 Display adverts yourself into our many exciting festivals. Events & festivals This is the birthplace of one of the world’s 58 Display adverts most beloved poets, Robert Burns. Come and breathe the same air, and walk over 64 Regional map the same glorious landscapes that inspired his beautiful poetry. What’s more, in 2017 we are celebrating our Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology, making this the perfect time to come and get a real feel for the characters, events, and traditions that Cover: Culzean Castle & Country Park, made this land so remarkable. -

Little, Ferries Interview Transcript

Project: Pennylands Camp 22 - WW2 POW Camp Respondent: Ferries James Little. Year of Birth: 1936. Age: 81. Connection to project: Was born and brought up on Dumfries House Estate. Date of Interview: 11th August 2017. Interviewer: Bobby Grierson. Recording Agreement: Yes Information & Content: Yes Photographic Images: Yes (Number of: 1) Location of Interview: Skype. Cumnock, Ayrshire. Full Transcript Introduction, welcome and information about respondent. Q1. What is your connection to Pennylands Camp? A1. I was born at Grimgrew one of the cottages on the Dumfries House Estate and I was aware of Pennylands from about the age of six and going round with my father who was the Shepherd on Dumfries House Estate and the camp had just been completed but was not occupied to that extent. It wasn’t a prisoner of war camp. The biggest problem they had was that the sewage treatment plant didn’t work because whoever had constructed it had only sealed the connections on top of the pipes with cement. The plant discharged into the river Lugar up river from the Lady’s Bridge. Q2 Can you tell me a little about your family, your parents and any siblings? A3. I was the only one. My mother Violet Cameron was also born and brought up on the estate and she was one of eight. Her father James Cameron was the estate joiner for 50 years as was his father before him. He lived at the Longrig, which is shown on one of the photos you have. There were two houses together at the bottom of the Longrig, one that faced onto the Longrig where John Murray lived and he had eight of a family. -

Exceptional, Superbly Presented Victorian Merchant's House

EXCEPTIONAL, SUPERBLY PRESENTED VICTORIAN MERCHANT’S HOUSE. glenrosa 85 loudon street, newmilns, ka16 9hq EXCEPTIONAL, SUPERBLY PRESENTED VICTORIAN MERCHANT’S HOUSE. glenrosa 85 loudon street, newmilns, ka16 9hq Reception Hall w sitting room w dining room w games room w victorian conservatory w family room w kitchen w larder w utility room w ground floor bedroom and bathroom w 4 further bedrooms w bathroom w shower room w loft room w 6 car garage w boiler house w workshop w vinery / greenhouse w wood store w enclosed walled garden w about 0.96 acres in all w EPC Rating: E Kilmarnock 7 miles, Glasgow 26 Miles, Prestwick 16 miles. Situation Glenrosa is arguably the finest house in Newmilns, occupying a prominent position, set back from the road in the East Ayrshire village of Newmilns. The property is very well located for easy access to Glasgow via the M77 (about 25 miles) and to Ayr (16 miles). Transport links within the area are excellent with a regular train service to Glasgow from Kilmarnock (7 miles) while Prestwick Airport is about 13 miles distant. Newmilns has both primary and secondary schooling with Mearns Castle High School topping the rankings. Private schooling is available at Wellington in Ayr and Belmont, Newton Mearns (14 miles). Kilmarnock has a wider range of amenities including restaurants, theatre, hospital, cinema and sports complex. The surrounding rolling countryside of the Irvine Valley offers a network of country lanes, ideal for walking, cycling and hacking. The popular Burn Anne Walk is a pleasant 5 mile circuit adjacent to the property. -

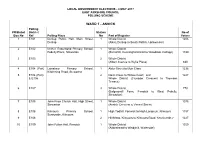

Polling Scheme

LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS - 4 MAY 2017 EAST AYRSHIRE COUNCIL POLLING SCHEME WARD 1 - ANNICK Polling PO/Ballot District Station No of Box No Ref Polling Place No Part of Register Voters 1 E101 Dunlop Public Hall, Main Street, 1 Whole District 1286 Dunlop (Aiket, Dunlop to South Pollick, Uplawmoor) 2 E102 Nether Robertland Primary School, 1 Whole District Pokelly Place, Stewarton (Barnahill, Cunninghamhead to Woodside Cottage) 1199 3 E103 2 Whole District (Albert Avenue to Wylie Place) 830 4 E104 (Part) Lainshaw Primary School, 1 Alder Street to Muir Close 1236 Kilwinning Road, Stewarton 5 E104 (Part) 2 Nairn Close to Willow Court; and 1227 & E106 Whole District (Crusader Crescent to Thomson Terrace) 6 E107 3 Whole District 770 (Balgraymill Farm, Fenwick to West Pokelly, Stewarton) 7 E105 John Knox Church Hall, High Street, 1 Whole District 1075 Stewarton (Annick Crescent to Vennel Street) 8 E108 Kilmaurs Primary School, 1 High Todhill, Fenwick to High Langmuir, Kilmaurs 1157 Sunnyside, Kilmaurs 9 E108 2 Hill Moss, Kilmaurs to Kilmaurs Road, Knockentiber 1227 10 E109 John Fulton Hall, Fenwick 1 Whole District 1350 (Aitkenhead to Windyhill, Waterside) 2 WARD 2 - KILMARNOCK NORTH Polling PO/Ballot District Station No of Box No Ref Polling Place No Part of Register Voters 11 E201 (Part) St John’s Parish Church Main Hall, 1 Altonhill Farm to Newmilns Gardens 1046 Wardneuk Drive, Kilmarnock 12 E201 (Part) 2 North Craig, Kilmarnock to Grassmillside, Kilmaurs 1029 13 E202 3 Whole District 1094 (Ailsa Place to Toponthank Lane) 14 E203 (Part) Hillhead -

Catrine's Other Churches

OTHER CHURCHES IN CATRINE THE UNITED SECESSION CHURCH (Later: The United Presbyterian Church) he 1891 Census states that in its early days the population of Catrine “…contained a goodly sprinkling of Dissenters…some of whom travelled to Cumnock to the TWhig Kirk at Rigg, near Auchinleck; but a much larger number went to the Secession Church at Mauchline. The saintly Mr Walker, minister there, becoming frail and not able to attend to all his flock, this (ie.1835) was thought to be a suitable time to take steps to have a church in Catrine”. An application for a site near the centre of the village was made to the Catrine Cotton Works Company, but this was refused by the then resident proprietor who said that: “He could not favour dissent.” A meeting of subscribers was held on 16th June 1835 when it was decided to approach Mr Claud Alexander of Ballochmyle with a request for ground. Mr Alexander duly granted them a site at the nominal sum of sixpence per fall. (A fall was equal to one square perch – about 30.25 square yards.) Another meeting of subscribers on 12th April 1836 authorised obtaining a loan of up to £350 to cover the cost of erecting a building on the site at the foot of Cowan Brae (i.e. at the corner where the present day Mauchline Road joins Ballochmyle Street). James Ingram of St.Germain Street, father of the eminent architect Robert Samson Ingram of Kilmarnock, was appointed to draw out plans. A proposal was approved to place a bottle containing the County newspaper in the foundation. -

The Ballads and Songs of Ayrshire

LIBRARY OF THE University of California. Class VZQlo ' i" /// s Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/balladssongsofayOOpaterich THE BALLADS AND SONGS OF AYRSHIRE, ILLUSTRATED WITH SKETCHES, HISTORICAL, TRADITIONAL, NARRATIVE AND BIOGRAPHICAL. Old King Coul was a merry old soul, And a jolly old soul was he ; Old King Coul he had a brown bowl, And they brought him in fiddlers three. EDINBURGH: THOMAS G. STEVENSON, HISTORICAL AND ANTIQUARIAN BOOKSELLER, 87 PRINCES STREET. MDCCCXLVII. — ; — CFTMS IVCRSI1 c INTRODUCTION. Renfrewshire has her Harp—why not Ayrshire her Lyre ? The land that gave birth to Burns may well claim the distinction of a separate Re- pository for the Ballads and Songs which belong to it. In this, the First Series, it has been the chief object of the Editor to gather together the older lyrical productions connected with the county, intermixed with a slight sprinkling of the more recent, by way of lightsome variation. The aim of the work is to collect those pieces, ancient and modern, which, scattered throughout various publications, are inaccessible to many readers ; and to glean from, oral recitation the floating relics of a former age that still exist in living remembrance, as well as to supply such in- formation respecting the subject or author as maybe deemed interesting. The songs of Burns—save, perhaps, a few of the more rare—having been already collected in numerous editions, and consequently well known, will form no part of the Repository. In distinguishing the Ballads and Songs of Ayrshire, the Editor has been, and will be, guided by the connec- tion they have with the district, either as to the author or subject ; and now that the First Series is before the public, he trusts that, whatever may be its defects, the credit at least will be given Jiim of aiming, how- ever feebly, at the construction of a lasting monument of the lyrical literature of Ayrshire. -

Experiences in Scotland

EXPERIENCES IN SCOTLAND XXX INTRODUCTIONXXX XX X XXX WELCOME TO CONTENTS BELMOND ROYAL SCOTSMAN EDINBURGH AND THE LOTHIANS 4-9 Browse this guide to discover KEITH 10-13 INVERNESS 14-17 an array of activities you can KYLE OF LOCHALSH 18-21 incorporate into your train journey BOAT OF GARTEN AND AVIEMORE 22-27 through the Scottish Highlands to PERTH 28-31 make it even more unforgettable. FORT WILLIAM 32-37 WEMYSS BAY AND KILMARNOCK 38-41 From river tubing in the Cairngorms ST ANDREWS 42-45 and dolphin spotting in the GOLF IN SCOTLAND 46-51 Moray Firth to making truffles STARGAZING 52-55 in Newtonmore and visiting the gleaming new V&A Dundee, there’s CATEGORIES plenty to appeal to all interests. ACTIVE Please speak to our team for prices CELEBRATION and any further information about the experiences. CHILD-FRIENDLY CULTURE Please note, some activities may only be available on select journeys due to the train’s CULINARY location and all are subject to availability. NATURE © 2019, Belmond Management Limited. All details are correct at time of publication May 2019. Images have been used for illustration purposes. BELMOND ROYAL SCOTSMAN 63 Edinburgh and the Lothians 4 BELMOND ROYAL SCOTSMAN BELMOND ROYAL SCOTSMAN 5 EDINBURGH AND THE LOTHIANS Edinburgh and the Lothians The cosmopolitan Scottish capital sits at the heart of miles of lush countryside and attractive coastline. Its unparalleled heritage and lively attractions captivate all ages. These activities are best experienced before or after your train journey. EDINBURGH BIKE TOUR Pedal through Edinburgh’s historic centre, enjoying sweeping views across the city’s dramatic skyline. -

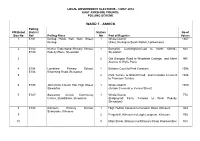

Polling Scheme for Local Elections

LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS - 3 MAY 2012 EAST AYRSHIRE COUNCIL POLLING SCHEME WARD 1 - ANNICK Polling PO/Ballot District Station No of Box No Ref Polling Place No Part of Register Voters 1 E101 Dunlop Public Hall, Main Street, 1 Whole District 1307 Dunlop (Aiket, Dunlop to South Pollick, Uplawmoor) 2 E102 Nether Robertland Primary School, 1 Barnahill, Cunninghamhead to North Kilbride, 928 E103 Pokelly Place, Stewarton Stewarton 3 2 Old Glasgow Road to Woodside Cottage; and Albert 995 Avenue to Wylie Place 4 E104 Lainshaw Primary School, 1 Balveny Court to Park Crescent 1096 E106 Kilwinning Road, Stewarton 5 2 Park Terrace to Strand Head; and Crusader Crescent 1088 to Thomson Terrace 6 E105 John Knox Church Hall, High Street, 1 Whole District 1050 Stewarton (Annick Crescent to Vennel Street) 7 E107 Stewarton Annick Community 1 Whole District 774 Centre, Standalane, Stewarton (Balgraymill Farm, Fenwick to West Pokelly, Stewarton) 8 E108 Kilmaurs Primary School, 1 High Todhill, Fenwick to Fenwick Road, Kilmaurs 869 Sunnyside, Kilmaurs 9 2 Fergushill, Kilmaurs to Laigh Langmuir, Kilmaurs 755 10 3 Main Street, Kilmaurs to Kilmaurs Road, Knockentiber 808 2 WARD 2 - KILMARNOCK NORTH Polling PO/Ballot District Station No of Box No Ref Polling Place No Part of Register Voters 11 E201 St John’s Parish Church Main Hall, 1 Altonhill Farm to Flotta Place 819 E202 Wardneuk Drive, Kilmarnock 12 2 Forest Grove to South Craig 856 13 3 South Woodhill, Kilmarnock to Grassmillside, 823 Kilmaurs; and Ailsa Place to Colonsay Place 14 4 Cumbrae Drive to Toponthank -

Christie's to Offer the Contents of Dumfries

For Immediate Release Friday, 13 April 2007 Contact: Rhiannon Broomfield +44 (0) 20 7389 2117 [email protected] Matthew Paton +44 (0) 20 7389 2965 [email protected] CHRISTIE’S TO OFFER THE CONTENTS OF DUMFRIES HOUSE IN JULY 2007 • Including the most important collection of Thomas Chippendale furniture ever offered at auction Dumfries House To be held at Christie’s, 8 King Street, St. James’s, London SW1Y 6QT Thursday, 12 July 2007 Friday, 13 July 2007 London - Christie’s announce that they will offer at auction the contents of Dumfries House on 12 and 13 July 2007 at King Street, London. Designed and built by John, Robert and James Adam between 1754 and 1759, the house contains the most important collection of Rococo furniture by Thomas Chippendale to remain in private hands, and the only fully documented furniture commission dating to his seminal Director period. A landmark auction in the history of collecting, the sale is expected to attract the interest of private collectors and institutions from around the world. Dumfries House and 1,940 acre estate will be brought to the market in the summer of 2007 by Savills. Charles Cator, Deputy Chairman of Christie’s International and Chairman of the International Furniture Department: “Christie’s is honoured to have been instructed to oversee the sale of the contents of Dumfries House in Ayrshire. One of the finest and most original collections of British furniture to remain in private hands, Dumfries House contains the only fully documented works of art dating from Chippendale’s illustrious Director Period, as well as the finest private collection of Scottish 18th century furniture. -

East Ayrshire Council East Ayrshire Council East Ayrshire

3448 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE 11 DECEMBER 1998 Alan Neish Dip TP MRTPI, Head of Planning and Building Control Proposed Change of use of Vacant Shop Premises and Alterations 6 Croft Street, Kilmarnock KA1 1JB to Same to Form Residential Accommodation Tel: (01563) 576790 A copy of the application form and plan may be inspected at the1 Council Offices, Lugar, Cumnock KA18 3JQ offices of the Department of Development Services at either 6 Tel: (01563) 555320 (950) Croft Street, Kilmarnock or the Council Offices, Lugar, Cumnock or by prior arrangement at one of the local offices throughout East Ayrshire. Any representations about the proposal should be made in writing East Ayrshire Council stating the grounds on which it is made and sent to the undersigned before the 2nd January 1999. PLANNING (LISTED BUILDINGS AND CONSERVATION Please note that comments received outwith the specified periods AREAS) (SCOTLAND) ACT 1997 will only be considered in exceptional circumstances which will be TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (LISTED BUILDING a question of fact in each case. Alan Neish Dip TP MRTPI, Head of Planning and Building Control AND BUILDINGS IN CONSERVATION AREAS) 6 Croft Street, Kilmarnock KA1 1JB (SCOTLAND) REGULATION 1987 Tel: (01563) 576790 Section 9 Council Offices, Lugar, Cumnock KA18 3JQ Notice of Application for.Listed Building Consent Tel: (01563) 555320 (970) Proposals to carry out works for altering AUCHINLECK HOUSE, AUCHINLECK ESTATE, AUCHINLECK East Ayrshire Council Notice is hereby given, that an application is being made to the East Ayrshire Council by Landmark Trust for Listed Building PLANNING (LISTED BUILDINGS AND CONSERVATION Consent for the following development: AREAS) (SCOTLAND) ACT 1997 Proposed restoration of existing buildings including main house TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (LISTED BUILDING pavilions and bridge. -

Tourism Strategy, 2007)

CONTENTS Page Number Executive Summary 3 VISION 4 - Our Vision 4 - Our Ambition 4 - The Way Ahead 5 POLICY CONTEXT 5 - National 5 - Regional 5 - Local 6 MARKET CONTEXT 7 - National - Scotland 8 - Regional – Ayrshire & Arran 8 - Local – East Ayrshire 8 - Emerging Trends 10 TOURISM PRODUCT & POTENTIAL 11 - History, Heritage & Ancestry 13 - Famous People 14 - Arts & Culture 16 - Leisure & Visitor Attractions 17 - Outdoor Activities & Nature Based Tourism 18 - Green Tourism 21 - Food & Drink 22 - Day Visits & Short Breaks 23 - Festivals & Events 24 - Business Tourism 25 - Golf 25 - Retail 26 TOURISM INFRASTRUCTURE 27 - Accommodation 27 - Accessibility & Transport 28 - People & Skills 30 - Information Communications Technology 31 MARKETING & PROMOTION 32 - Image & Brand 32 - Marketing 33 - Tourist Information 34 DELIVERY 35 - Implementation 35 - Performance Measurement 38 2 Executive Summary This document outlines our vision for the tourism industry in East Ayrshire over the next six years to 2015, and describes how the area will contribute over this timescale to the national growth target set by the Scottish Government of 50% real terms growth in tourism revenues by 2015. The key principle, which underpins the direction, is to create and develop links with and between public sector economic regeneration agencies, tourism businesses in the private sector and attractions and facilities operated by the public sector, and communities within East Ayrshire to work together towards a shared vision for tourism. This is vital to ensure that it is implemented and further developed over the next seven years. East Ayrshire has an existing tourism product comprising of history and heritage, cultural venues and visitor attractions, and natural environment providing opportunities for a range of outdoor activities and recreation.