Y-BOCS Has Become the Gold Standard for Rating Symptom Severity in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Y-BOCS™ (Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale) Principal Developer: Wayne K. Goodman, M.D. Co-Developers: Steven A. Rasmussen

FIRST EDITION 9/89 (Revised 05/20) Y-BOCS™ (Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale) Principal Developer: Wayne K. Goodman, M.D. Co-developers: Steven A. Rasmussen, M.D. Lawrence H. Price, M.D. Eric A. Storch, PhD. Investigators interested in using this rating scale should contact Dr. Goodman at <[email protected]>. © 1989, 2017 Wayne Goodman Additional information regarding the development, use, and psychometric properties of the Y-BOCS™ can be found in Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al.: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: Part I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry (46:1006-1011, 1989). and Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al.: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale): Part II. Validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry (46:1012-1016, 1989). Copies of a version of the Y-BOCS™ modified for use in children, the Children's Y-BOCS™ (CY-BOCS™) (Goodman WK, Rasmussen SA, & Price LH,), or the second editions of the Y-BOCS-II™ and CY-BOCS-II™ are available from Dr. Goodman on request. Y-BOCS™ General Instructions This rating scale is designed to rate the severity and record the types of symptoms in a patient diagnosed with obsessive- compulsive disorder (OCD). In general, the items depend on the patient's report; however, the final rating is based on the clinical judgment of the interviewer. Rate the characteristics of each item during the prior week up until and including the time of the interview. Scores should reflect the average (mean) occurrence of each item for the entire week. This rating scale is intended for use as a semi-structured interview. -

Self-Ambivalence in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Self-Ambivalence in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Sunil S Bhar Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July, 2004 Produced on acid-free paper Department of Psychology University of Melbourne ii iii Abstract According to the cognitive model, Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is maintained by various belief factors such as an inflated sense of responsibility, perfectionism and an overestimation about the importance of thoughts. Despite much support for this hypothesis, there is a lack of understanding about the role of self-concept in the maintenance or treatment of OCD. Guidano and Liotti (1983) suggest that individuals who are ambivalent about their self-worth, personal morality and lovability use perfectionistic and obsessive compulsive behaviours to continuously restore self- esteem. This thesis develops a model of OCD that integrates self-ambivalence in the cognitive model of OCD. Specifically, it explored the hypothesis that the OCD symptoms and the belief factors related to the vulnerability of OCD are mechanisms that provide relief from self- ambivalence. It addressed three questions. First, is self-ambivalence related to OCD symptoms and OCD-related beliefs? Second, to what extent is self-ambivalence specific to OCD, compared to other anxiety disorders? Third, to what extent is self-ambivalence important in accounting for response and relapse of OCD to psychological interventions? In order to explore these questions, a questionnaire measuring self- ambivalence was first developed and evaluated. Non clinical and clinical participants were recruited for research. Non-clinical participants (N = 269) comprised undergraduate students (N = 226: mean age = 19.55; SD = 3.27) and community controls (N = 43; mean age = 43.78; SD = 3.92). -

Quick-View Guides

Appendix A Quick-View Guides Compiled by Jennifer S. Mills 310 APPENDIX A QUICK-VIEW GUIDES 311 312 APPENDIX A QUICK-VIEW GUIDES 313 314 APPENDIX A QUICK-VIEW GUIDES 315 316 APPENDIX A QUICK-VIEW GUIDES 317 Appendix B Reprinted Measures Measures for Anxiety and Related Constructs 322 APPENDIX B Anxiety Control Questionnaire (ACQ) Listed below are a number of statements describing a set of beliefs. Please read each statement carefully and, on the 0–5 scale below, indicate how much you think each statement is typical of you. 1. I am usually able to avoid threat quite easily. 2. How well I cope with difficult situations depends on whether I have outside help. 3. When I am put under stress, I am likely to lose control. 4. I can usually stop my anxiety from showing. 5. When I am frightened by something, there is generally nothing I can do. 6. My emotions seem to have a life of their own. 7. There is little I can do to influence people’s judgments of me. 8. Whether I can successfully escape a frightening situation is always a matter of chance with me. 9. I often shake uncontrollably. 10. I can usually put worrisome thoughts out of my mind easily. 11. When I am in a stressful situation, I am able to stop myself from breathing too hard. 12. I can usually influence the degree to which a situation is potentially threatening to me. 13. I am able to control my level of anxiety. 14. There is little I can do to change frightening events. -

Double Blind Randomized Controlled Trial of Deep Brain Stimulation for Obsessive- Compulsive Disorder: Clinical Trial Design

UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works Title Double blind randomized controlled trial of deep brain stimulation for obsessive- compulsive disorder: Clinical trial design. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/93m0r1w4 Authors McLaughlin, Nicole CR Dougherty, Darin D Eskandar, Emad et al. Publication Date 2021-06-05 DOI 10.1016/j.conctc.2021.100785 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications 22 (2021) 100785 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/conctc Double blind randomized controlled trial of deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Clinical trial design Nicole C.R. McLaughlin a,b,*, Darin D. Dougherty c,d, Emad Eskandar c,d,1,2, Herbert Ward e, Kelly D. Foote f, Donald A. Malone g, Andre Machado g, William Wong h, Mark Sedrak i, Wayne Goodman j,3, Brian H. Kopell j, Fuad Issa k, Donald C. Shields l, Osama A. Abulseoud m, Kendall Lee n, Mark A. Frye n, Alik S. Widge c,d,o,4, Thilo Deckersbach p, Michael S. Okun f, Dawn Bowers q, Russell M. Bauer q, Dana Mason e, Cynthia S. Kubu g, Ivan Bernstein h, Kyle Lapidus r, David L. Rosenthal j,5, Robert L. Jenkins k, Cynthia Read a, Paul F. Malloy a,b, Stephen Salloway a,b, David R. Strong s, Richard N. Jones b, Steven A. Rasmussen a,b, Benjamin D. Greenberg a,b,t a Butler Hospital, 345 Blackstone Blvd, Providence, RI, 02906, USA b Alpert Medical School of Brown University, -

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Wayne K. Goodman, MD. ADDRESS: Department of Psychiatry University of Florida College of Medicine Mcknigh

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Wayne K. Goodman, MD. ADDRESS: Department of Psychiatry University of Florida College of Medicine McKnight Brain Institute, Suite L4-100 100 Newell Drive Gainesville, FL 32611 ------------------------------------------------------------ --------------------------- PERSONAL --------------------- DATA: ----------------------------------------------------------- CAREER: 1998- Chairman, Department of Psychiatry, University of Florida College of Medicine 1998- Psychiatrist-in-Chief, Shands Healthcare, Gainesville, FL 1997-1998 Interim Chairman, Department of Psychiatry, University of Florida College of Medicine 1997-1999 Associate Chairman, Department of Psychiatry, University of Florida, Jacksonville, FL 1993-1997 Director, Psychiatric Specialty Clinics, Shands Hospital at the University of Florida College of Medicine 1993- Chief, Obsessive-Compulsive and Tourette's Disorders Clinic, Department of Psychiatry, University of Florida College of Medicine 1993-2001 Director, Clinical Trials Program, Department of Psychiatry, University of Florida College of Medicine 1993- Professor (Tenured), Department of Psychiatry, University of Florida College of Medicine 1992-1993 Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine 1990-1993 Associate Unit Chief, Clinical Neuroscience Research Unit, Yale University School of Medicine 1986-1992 Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine 1985-1992 Chief and founder, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Clinic, Yale University -

Adrenergic and Glutamergic Receptor Gene Expression

ADRENERGIC AND GLUTAMERGIC RECEPTOR GENE EXPRESSION AND THEIR FUNCTIONAL REGULATION IN THE CEREBRAL CORTEX OF HYPOXIA INDUCED NEONATAL RATS: ROLE OF OXYGEN, EPINEPHRINE AND GLUCOSE SUPPLEMENTATION THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BIOTECHNOLOGY UNDER THE FACtJLTY Of. SCIENCE OF COCHlN llNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY BY FINLA CHATHU DEPARTMENT OF BIOTECHNOLOGY COCHIN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COCHIN - 682 022. KERALA, INDIA. FEBRUARY 2007 DEPARTMENT OF BIOTECHNOLOGY COCHIN UNIVERSITY Of' SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COCHIf- 6IZ GZJ, ItID&A ....: 04I4-U7ut7 tol. oe-Ul1CH (I.) IIrlb: M41V 114ZJ r-t: It tell. et K In, pet ........OD... fa: " ......157U61. J577595 DR. C.S._LOSE HEAD DIRECTOR, CENTRE FOR NWROSCIEHCE This is 10 certify that the thesis entitled "ADRINERGIC AND GLUT.uR.RGIC UCEI'TOR GRNE IXPRl:SSION AND THEIR J'UNCflONAL RlGULA.'nON IN mE Cl.UBRAL coarex OF HYPOXIA INDUCltD NWNATAL RATS: ROLE O' OXYGEN. UINIPHRlNE AND GUJCOSE SUPPLEMJ:NTATION'" is a bonafide record of the resean::h work carried out by Ms. Fial. Cbathu.. under my guidance and supervision in the Department of Biotec:bnology. Cochin Uaiversity of Science and Tecb.nology and that DO pan thereof has been presented for theaward ofany other degree. Cochin 682 022 2-02-07 Or. C.S. PAUlO SE M se. Ph.D. FIM$A. FGSI DIRECTOR, CE NTRF t · <;r-IENCE HEAD. DEFT. C ..... LOGY Cochin Unlvers .yor ~ ... Technology Cochin·682 012, Ke rclc, India DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis entitled "ADRENERGIC AND GLUTAMERGIC RECEPTOR GENE EXPRESSION AND THEIR FUNCTIONAL REGULATION IN THE CEREBRAL CORTEX OF HYPOXIA INDUCED NEONATAL RATS: ROLE OF OXYGEN, EPINEPHRINE AND GLUCOSE SUPPLEMENTATION" is based on the original research carried out by me at the Department of Biotechnology. -

July 27–29, 2018With Pre-Conference Activities on July 26

Organized by: Presented by: PROGRAM GUIDE July 27–29, 2018 with Pre-Conference Activities on July 26 Hope and healing begin here When intrusive thoughts, rituals, worries, and fears get in the way of enjoying life, Rogers Behavioral Health is here. With more than 110 years of experience, today Rogers is a leading provider of residential, partial hospitalization, and intensive outpatient treatment for children, teens, and adults living with OCD. Programs are led by a board-certified psychiatrist and multidisciplinary care team who work each day to help patients gain control and find relief from the complications of their OCD. Evidence-based treatment incorporates: • Cognitive behavioral therapy • Exposure and response prevention • Medication management • Individual, group, and family therapy • Experiential therapy Does our treatment work? See the results at rogersbh.org/clinicaloutcomes. To learn more, Visit rogersbh.org or call 800-767-4411 today. International OCD Foundation | iocdf.org Welcome to the 25TH Annual OCD Conference Hello Conference Attendees!!! • The theme of Substance Use Disorder recognition We are excited to welcome you to Washington DC for and treatment will run throughout the Conference — the 25th Annual OCD Conference. This great city holds so from a training for professionals on Thursday night Hope and healing much history, and now you are a part of it. By attending to panels for all participants run by those who have this Conference, you are already involved in increasing lived through addiction. awareness, empowering research, and reducing the stigma • Near to my heart, check out the 2nd year of our associated with OCD and related disorders. -

GUÍA PRÁCTICA DEL TRASTORNO OBSESIVO COMPULSIVO Pistas Para Su Liberación

GUÍA PRÁCTICA DEL TRASTORNO OBSESIVO COMPULSIVO Pistas para su liberación Bruce M. Hyman y Cherry Pedrick GUÍA PRÁCTICA DEL TRASTORNO OBSESIVO COMPULSIVO Pistas para su liberación Desclée De Brouwer Título de la edición original: The OCD Workbook. Your Guide to Breaking Free From Obsesive-Compulsive Disorder. © 1999, New Harbinger Publications Inc., Oakland Traducción: Victor M. Arnáiz Adrián © EDITORIAL DESCLÉE DE BROUWER, S.A., 2003 Henao, 6 - 48009 BILBAO www.edesclee.com [email protected] Queda prohibida, salvo excepción prevista en la ley, cualquier forma de reproducción, dis- tribución, comunicación pública y transformación de esta obra sin contar con la autoriza- ción de los titulares de propiedad intelectual. La infracción de los derechos mencionados puede ser constitutiva de delito contra la propiedad intelectual (arts. 270 y sgts. del Código Penal). El Centro Español de Derechos Reprográficos (www.cedro.org) vela por el respeto de los citados derechos. Diseño de colección: Luis Alonso Impreso en España-Printed in Spain ISBN: 978-84-330-1821-2 Depósito Legal: Impresión: Publidisa, S.A. - Sevilla Índice Reconocimientos . 13 Prólogo . 15 Introducción . 21 Quiénes somos . 21 Cómo puede ayudarle este libro . 25 Sobre este libro . 26 PRIMERA PARTE . 29 1. ¿Qué es el trastorno obsesivo compulsivo? . 31 Tipos básicos del trastorno obsesivo compulsivo . 32 El trastorno obsesivo compulsivo en el tiempo . 39 2. Entonces tiene un problema: ¿Cuál es? . 43 Una mirada exhaustiva al trastorno obsesivo compulsivo . 43 Lo que no es un trastorno obsesivo compulsivo . 45 Los síntomas del trastorno obsesivo compulsivo . 49 ¿Cómo se diagnostica el trastorno obsesivo compulsivo? . 55 Trastorno obsesivo compulsivo y vergüenza . -

For Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (Ocd)

1 DEVELOPMENT OF THERAPEUTIC PROTOCOL OF COGNITIVE BEHAVIOR THERAPY (CBT) FOR OBSESSIVE COMPULSIVE DISORDER (OCD) IN PAKISTAN KIRAN ISHFAQ 063-GCU-PHD-PSY-08 Department of Psychology G. C. University (GCU), Lahore, Pakistan 2 3 4 5 6 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF TABLES i LIST OF FIGURES ii LIST OF APPENDICES iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT vii CHAPTER 1 Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) 1 Types 1 Prevalence 2 Diagnostic Tools 3 Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale-Checklist (Y-BOCS-SC) 4 Etiology: Behavioral Approach 5 Cognitive Behavior Approach 5 Beck‘s Cognitive Model 7 Salkovskis‘s Inflated Responsibility Model 8 Clark‘s Model 8 The Meta-Cognitive Model 9 Assessment in CBT 9 Obsessive Belief Questionnaire-44 (OBQ-44) 10 Treatment 11 Exposure and Response Prevention (E & RP) 12 Cognitive Behavior therapy (CBT) for OCD 13 Significance of CBT Models for OCD 14 CBT with Specific types of OCD 20 CBT Efficacy for Cognitive Change 24 CBT with Specific Groups 27 8 Different Formats of CBT 28 CBT and Quality of Life (QOL) 33 Meta-Analysis Studies 34 CBT in Eastern Cultures 38 CBT in Pakistan 41 Rationale of the Study 42 CHAPTER 2—METHOD Study 1 Objective 44 Inquiry & Secondary Questions 44 Sample 45 Instruments 45 Procedure 46 Ethical Considerations 47 Study 2 Objectives 48 Hypothesis 48 Sample 49 Instrument 50 Procedure 52 Data Analysis 53 Ethical Considerations 53 Study 3 Objectives 53 Hypotheses 54 Sample 54 Research Design 55 Instrument 55 9 Procedure 56 Data Analysis 56 Ethical Considerations 57 Study 4 Objectives 57 Sample 58 Instrument 58 Research Design 58 Research Questions 54 Procedure 59 Data Analysis 59 Ethical Considerations 59 CHAPTER 3—RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Study 1 Results 60 Discussion 79 Study 2 Results 83 Discussion 96 Study 3 Results 106 Discussion 111 Study 4 Results 116 Discussion 123 CHAPTER 4—GENERAL DISCUSSION 127 Limitations 134 Significance of Study 134 Future Implications 135 References 136 10 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Benjamin David Greenberg, MD Phd EDUCATION Undergraduate: Amherst College Medical School: University of Miami

CURRICULUM VITAE Benjamin David Greenberg, MD PhD EDUCATION Undergraduate: Amherst College Medical School: University of Miami Graduate School: University of California, San Diego (UCSD), Neurosciences POSTGRADUATE TRAINING Residency: New York University VA Medical Center Internship in Internal Medicine Neurological Institute of New York, Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Resident in Neurology Johns Hopkins Hospital Residency in Psychiatry Fellowships: Harvard School of Public Health, Postdoctoral Fellowship, Interdisciplinary Programs in Health National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Program, Senior Staff Fellow (Commissioned Corps), Section on Clinical Neuropharmacology, Laboratory of Clinical Science POSTGRADUATE HONORS AND AWARDS Best Review Article of the Year, CNS Spectrums, 2003 Research Mentor Award, Brown University Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, 2001 Early Career Award, EEG and Clinical Neuroscience Society (ECNS), 10/2001 APA/SmithKline Beecham Young Faculty Award, Hon. Mention, 2000 Young Investigator Award, American Neuropsychiatric Assn, 1995 DISTA Fellowship, Society of Biological Psychiatry, 1991 PROFESSIONAL LICENCES AND BOARD CERTIFICATION Rhode Island Medical License Maryland Medical License Diplomate in Psychiatry, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University 2/2000 - Present Greenberg 2 Chief, Adult Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Research Unit, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda MD, 7/96-1/2000 -

Baylor College of Medicine OCD Program

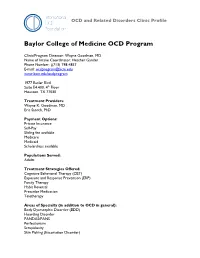

OCD and Related Disorders Clinic Profile Baylor College of Medicine OCD Program Clinic/Program Director: Wayne Goodman, MD Name of Intake Coordinator: Heather Gander Phone Number: ((713) 798-4857 E-mail: [email protected] www.bcm.edu/ocdprogram 1977 Butler Blvd Suite E4.400, 4th Floor Houston, TX 77030 Treatment Providers: Wayne K. Goodman, MD Eric Storch, PhD Payment Options: Private Insurance Self-Pay Sliding fee available Medicare Medicaid Scholarships available Populations Served: Adults Treatment Strategies Offered: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) Family Therapy Habit Reversal Prescribe Medication Teletherapy Areas of Specialty (in addition to OCD in general): Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) Hoarding Disorder PANDAS/PANS Perfectionism Scrupulosity Skin Picking (Excoriation Disorder) Tics/Tourettes Trichotillomania (Hair Pulling Disorder) Violent/Sexual Obsessions Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) Summary of our services: At the BCM OCD program we evaluate and treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and related conditions, including body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), hoarding, and trichotillomania. In addition to direct outpatient ERP treatment and pharmacology for OCD, we specialize in OCD that has not responded to first line therapeutic approaches through device-based interventions including deep brain stimulation (DBS). At BCM we conduct research focused on the neurobiology of OCD with the goal of discovering the causes of these disorders and identifying the pathways to developing more effective therapies. Our research includes the use of brain imaging, genetic testing, behavioral & pharmacological therapies, and NIH-funded studies of DBS. We employ experts in the OCD field including leading psychiatrist Dr. Wayne Goodman who has over 25 years of experience in OCD, was the co-founder of the IOCDF and principal developer of the Y-BOCS. -

Tuesday, December 13, 2005 Poster Session II

Neuropsychopharmacology (2005) 30, S143-S209 © 2005 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0893-133X/05 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org S143 Tuesday, December 13, 2005 the context of cocaine delivery can alter the neurochemical responses to Poster Session II - Tuesday the drug. In addition, increasing evidence suggests that stress can also in- fluence COC reinforcement through extrahypothalamic brain regions. The present study was designed to determine differences in the neuro- 1. Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Cocaine Dependence: Evidence for chemical and neuroendocrine responses to COC during response-con- Reduced Myelin in the Anterior Corpus Callosum tingent and response-independent COC administration in rats. F. Gerard Moeller*, Khader M Hassan, Joel L Steinberg, Ignacio Methods: Male Wistar rats were divided into triads of 3 rats each: Valdes, Larry Kramer, Ponnada A Narayana and Alan C Swann one rat was selected as the self-administration (SA) rat, while the Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Univ. of Texas Health Sci. Center other two rats were designated as the yoked-cocaine (YC) and yoked- at Houston, Houston, TX, USA saline (YS) rats, respectively. Rats were implanted with jugular Sponsor: Alan Swann catheters and a microdialysis guide cannula aimed at the medial pre- frontal cortex (MPC). SA rats were trained to self-administer cocaine Background: Fractional anisotropy (FA) as measured by diffusion (0.25 mg/kg/inf) under a fixed-ratio 2 schedule of reinforcement; 20- tensor imaging (DTI) is becoming increasingly used as a measure min samples were collected 2 hrs prior to, during and after the SA of subtle white matter pathology in psychiatric populations. How- session.