Litigating a Slip, Trip and Fall Case in New York State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© Gibbel Kraybill & Hess LLP 2015

© Gibbel Kraybill & Hess LLP 2015 Everence Stewardship University Session A3 J. Doe v. Church Presented by GKH Attorney Peter J. Kraybill March 7, 2015 © Gibbel Kraybill & Hess LLP 2015 J. Doe v. Church Churches are not as “special” to outsiders, whether those outsiders are • cyber squatters • copyright holders • banks or • slip-and-fall victims Churches often will be treated as equal to businesses or other “legal entities” for purposes of • contract law • trademarks • copyrights and • negligence, among others. How can churches be protective and proactive when engaging with the world? Legal Threats State action versus Private action (government enforcement compared to civil litigation) State Action What about the government going after a church? US Constitution - Bill of Rights - First Amendment - Freedom of Religion - "Free exercise” clause: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof… http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/free_exercise_clause Free Exercise Clause The Free Exercise Clause reserves the right of American citizens to accept any religious belief and engage in religious rituals. The clause protects not just those beliefs but actions taken for those beliefs. Specifically, this allows religious exemption from at least some generally applicable laws, i.e. violation of laws is permitted, as long as that violation was for religious reasons. In 1940, the Supreme Court held in Cantwell v. Connecticut that, due to the Fourteenth Amendment, the Free Exercise Clause is enforceable against state and local governments. http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/free_exercise_clause Extra credit: Famous example of the Amish using the Free Exercise Clause? Wisconsin v. -

The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 22 | Number 1 Symposium: Assumption of Risk Symposium: Insurance Law December 1961 The lP ace of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade Repository Citation John W. Wade, The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La. L. Rev. (1961) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol22/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade* The "doctrine" of assumption of risk is a controversial one, and there is considerable disagreement as to the part which it should play in a negligence case.' On the one hand it has a be- guiling simplicity about it, offering the opportunity of easily disposing of certain cases on a single issue without the need of giving consideration to other, more difficult, issues. On the other hand it overlaps and duplicates certain other doctrines, and its simplicity proves to be misleading because of its failure to point out the policy problems which may be more adequately presented by the other doctrines. Courts disagree as to the scope of the doctrine, some of them confining it to the situation where there is a contractual relation between the parties,2 and others expanding it to any situation in which an action might be brought for negligence.3 Text- writers and commentators commonly criticize the wide applica- tion of the doctrine, and not infrequently suggest that the doc- trine is entirely tautological. -

Chapter 668 Liability in Tort — Comparative Fault

1 LIABILITY IN TORT — COMPARATIVE FAULT, §668.3 CHAPTER 668 LIABILITY IN TORT — COMPARATIVE FAULT Referred to in §321J.4B, 625.21 668.1 Fault defined. 668.11 Disclosure of expert witnesses 668.2 Party defined. in liability cases involving 668.3 Comparative fault — effect — licensed professionals. payment method. 668.12 Liability for products — defenses. 668.4 Joint and several liability. 668.13 Interest on judgments. Evidence of previous payment or 668.5 Right of contribution. 668.14 future right of payment. 668.6 Enforcement of contribution. 668.14A Recoverable damages for medical 668.7 Effect of release. expenses. 668.8 Tolling of statute. 668.15 Damages resulting from sexual 668.9 Insurance practice. abuse — evidence. 668.10 Governmental exemptions. 668.16 Applicability of this chapter. 668.1 Fault defined. 1. As used in this chapter, “fault” means one or more acts or omissions that are in any measure negligent or reckless toward the person or property of the actor or others, or that subject a person to strict tort liability. The term also includes breach of warranty, unreasonable assumption of risk not constituting an enforceable express consent, misuse of a product for which the defendant otherwise would be liable, and unreasonable failure to avoid an injury or to mitigate damages. 2. The legal requirements of cause in fact and proximate cause apply both to fault as the basis for liability and to contributory fault. 84 Acts, ch 1293, §1 See also §619.17 668.2 Party defined. As used in this chapter, unless otherwise required, “party” means any of the following: 1. -

The Slip and Fall of the California Legislature in the Classification of Personal Injury Damages at Divorce and Death

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Publications Faculty Scholarship Summer 2009 The liS p and Fall of the California Legislature in the Classification of Personal Injury Damages At Divorce and Death Helen Y. Chang Golden Gate University - San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation 1 Estate Plan. & Comm. Prop. L. J. 345 (2009). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SLIP AND FALL OF THE CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE IN THE CLASSIFICATION OF PERSONAL INJURY DAMAGES AT DIVORCE AND DEATH by Helen Y. Chang* I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 345 II. CALIFORNIA'S HISTORICAL TREATMENT OF PERSONAL INJURY D AM AGES .......................................................................................... 347 A. No-Fault Divorce and the Principleof Equality ...................... 351 B. Problems with the CurrentCalifornia Law .............................. 354 1. The Cause ofAction 'Arises'PerFamily Code Section 2 603 ...................................................................................355 2. Division of PersonalInjury Damages at Divorce.............. 358 3. The Classification of PersonalInjury Damages -

Slip and Fall.Pdf

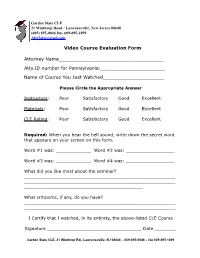

Garden State CLE 21 Winthrop Road • Lawrenceville, New Jersey 08648 (609) 895-0046 fax- 609-895-1899 [email protected] Video Course Evaluation Form Attorney Name____________________________________ Atty ID number for Pennsylvania:______________________ Name of Course You Just Watched_____________________ ! ! Please Circle the Appropriate Answer !Instructors: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent !Materials: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent CLE Rating: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent ! Required: When you hear the bell sound, write down the secret word that appears on your screen on this form. ! Word #1 was: _____________ Word #2 was: __________________ ! Word #3 was: _____________ Word #4 was: __________________ ! What did you like most about the seminar? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________ ! What criticisms, if any, do you have? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ! I Certify that I watched, in its entirety, the above-listed CLE Course Signature ___________________________________ Date ________ Garden State CLE, 21 Winthrop Rd., Lawrenceville, NJ 08648 – 609-895-0046 – fax 609-895-1899 GARDEN STATE CLE LESSON PLAN A 1.0 credit course FREE DOWNLOAD LESSON PLAN AND EVALUATION WATCH OUT: REPRESENTING A SLIP AND FALL CLIENT Featuring Robert Ramsey Garden State CLE Senior Instructor And Robert W. Rubinstein Certified Civil Trial Attorney Program -

Assumption of Risk, Waiver, and Release of Liability

Rev. 4/30/2020 ASSUMPTION OF RISK, WAIVER, AND RELEASE OF LIABILITY READ THIS ASSUMPTION OF RISK, WAIVER AND RELEASE OF LIABILITY BEFORE YOU SIGN IT. IT AFFECTS YOUR LEGAL RIGHTS. I, ____________________________ [print student’s name], agree to act in a responsible and safe manner during my participation in the ____________________________ “the Program.” I acknowledge and agree that I must comply with the rules and requirements of the Program, any other applicable University policy, and all applicable local, state, and federal law. I agree to follow the instructions issued by Program directors and staff. I will also abide by signage posted on the University’s campus. I understand that I may be dismissed from the Program for misconduct. I understand that my participation in the Program is voluntary, and I may be exposed to risks and hazards that could result in serious illness, bodily injury, disability, or death. These risks and hazards may include, but are not limited to: (i) vehicular, pedestrian, or other accidents, such as drowning, (ii) storms, floods, fires, earthquakes, and other natural disasters, (iii) infectious diseases or viruses, including but not limited to COVID-19, (iv) limited or inadequate medical care, (v) inadequate design, safety, and maintenance of buildings and public places, (vi) terrorist activities, and (vii) allergic reactions to food, insects, or other allergens. I also understand that during the Program I may use or access educational computer applications, web-based services, or online content that could expose me to certain cyber risks, including but not limited to, cyber predators, data mining, phishing, viruses, malware, data breaches, cyberbullying, exploitation, victimization, cyber stalking, online grooming, reputational loss, brand hijacking, and image replication. -

Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline 1

Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline 1. Introduction 2. The Basis of Tort Law 3. Intentional Torts 4. Negligence 5. Cyber Torts: Defamation Online 6. Strict Liability 7. Product Liability 8. Defenses to Product Liability 9. Tort Law and the Paralegal Chapter Objectives After completing this chapter, you will know: • What a tort is, the purpose of tort law, and the three basic categories of torts. • The four elements of negligence. • What is meant by strict liability and under what circumstances strict liability is applied. • The meaning of strict product liability and the underlying policy for imposing strict product liability. • What defenses can be raised in product liability actions. Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline I. INTRODUCTION A. Torts are wrongful actions. B. The word tort is French for “wrong.” II. THE BASIS OF TORT LAW A. Two notions serve as the basis of all torts. i. Wrongs ii. Compensation B. In a tort action, one person or group brings a personal-injury suit against another person or group to obtain compensation or other relief for the harm suffered. C. Tort suits involve “private” wrongs, distinguishable from criminal actions that involve “public” wrongs. D. The purpose of tort law is to provide remedies for the invasion of various interests. E. There are three broad classifications of torts. i. Intentional Torts ii. Negligence iii. Strict Liability F. The classification of a particular tort depends largely on how the tort occurs (intentionally or unintentionally) and the surrounding circumstances. Intentional Intentions An intentional tort requires only that the tortfeasor, the actor/wrongdoer, intended, or knew with substantial certainty, that certain consequences would result from the action. -

SCC File No. 39108 in the SUPREME COURT of CANADA (ON APPEAL from the COURT of APPEAL for BRITISH COLUMBIA) BETWEEN: CITY OF

SCC File No. 39108 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR BRITISH COLUMBIA) BETWEEN: CITY OF NELSON APPLICANT (Respondent) AND: TARYN JOY MARCHI RESPONDENT (Appellant) ______________________________________________ MEMORANDUM OF ARUMENT OF THE RESPONDENT (Pursuant to Rule 27 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada) ______________________________________________ DAROUX LAW CORPORATION MICHAEL J. SOBKIN 1590 Bay Avenue 33 Somerset Street West Trail, B.C. V1R 4B3 Ottawa, ON K2P 0J8 Tel: (250) 368-8233 Tel: (613) 282-1712 Fax: (800) 218-3140 Fax: (613) 288-2896 Danielle K. Daroux Michael J. Sobkin Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Respondent, Taryn Joy Marchi Agent for Counsel for the Respondent MURPHY BATTISTA LLP #2020 - 650 West Georgia Street Vancouver, B.C. V6B 4N7 Tel: (604) 683-9621 Fax: (604) 683-5084 Joseph E. Murphy, Q.C. Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Respondent, Taryn Joy Marchi ALLEN / MCMILLAN LITIGATION COUNSEL #1550 – 1185 West Georgia Street Vancouver, B.C. V6E 4E6 Tel: (604) 569-2652 Fax: (604) 628-3832 Greg J. Allen Tele: (604) 282-3982 / Email: [email protected] Liam Babbitt Tel: (604) 282-3988 / Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Applicant, City of Nelson 1 PART I – OVERVIEW AND STATEMENT OF FACTS A. Overview 1. The applicant City of Nelson (“City”) submits that leave should be granted because there is lingering confusion as to the difference between policy and operational decisions in cases of public authority liability in tort. It cites four decisions in support of this proposition. None of those cases demonstrate any confusion on the part of the lower courts. -

Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory Into Tort Doctrine John L

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 1991 Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine John L. Diamond UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation John L. Diamond, Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine, 52 Ohio St. L.J. 717 (1991). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/103 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Publications UC Hastings College of the Law Library Diamond John Author: John L. Diamond Source: Ohio State Law Journal Citation: 52 Ohio St. L.J. 717 (1991). Title: Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine Originally published in OHIO STATE LAW JOURNAL. This article is reprinted with permission from OHIO STATE LAW JOURNAL and Ohio State University Michael E. Moritz College of Law. Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine JOHN L. DIAMOND* I. INTRODUCTION The confusion generated by the doctrine of assumption of risk' is illustrated by the contradicting responses to the following hypothetical: - 0 1991 John L. Diamond. Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law. B.A., Yale College; J.D., Columbia Law School; Dip. -

Nuisance – Elements

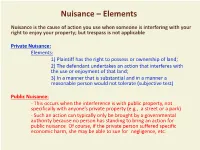

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

When the Bough Breaks: a Proposal for Georgia Slip and Fall Law After Alterman Foods, Inc. V. Ligon Daniel W

Urban Law Annual ; Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law Volume 55 January 1999 When the Bough Breaks: A Proposal for Georgia Slip and Fall Law After Alterman Foods, Inc. v. Ligon Daniel W. Champney Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_urbanlaw Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel W. Champney, When the Bough Breaks: A Proposal for Georgia Slip and Fall Law After Alterman Foods, Inc. v. Ligon, 55 Wash. U. J. Urb. & Contemp. L. 073 (1999) Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_urbanlaw/vol55/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Law Annual ; Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHEN THE BOUGH BREAKS: A PROPOSAL FOR GEORGIA SLIP AND FALL LAW AFTER ALTERMAN FOODS, INC. V LIGON INTRODUCTION Before the Georgia Supreme Court's recent decision in Robinson v. Kroger Co.' ("Robinson"), the authors of a yearly survey of Georgia tort law succinctly described the status of the subset of commercial premises liability law known as slip-and-fal 2 cases by stating: "Something is fundamentally wrong with the appellate standard of review for slip and fall cases in Georgia.",3 The problems 1. 493 S.E.2d 403 (Ga. 1997) (reexamining Georgia's slip-and-fall law for the first time since Barentine v. Kroger Co., 443 S.E.2d 485 (Ga. -

State of Wyoming Retail and Hospitality Compendium of Law

STATE OF WYOMING RETAIL AND HOSPITALITY COMPENDIUM OF LAW Prepared by Keith J. Dodson and Erica R. Day Williams, Porter, Day & Neville, P.C. 159 North Wolcott, Suite 400 Casper, WY 82601 (307) 265-0700 www.wpdn.net 2021 Retail, Restaurant, and Hospitality Guide to Wyoming Premises Liability Introduction 1 Wyoming Court Systems 2 A. The Wyoming State Court System 2 B. The Federal District Court for the District of Wyoming 2 Negligence 3 A. General Negligence Principles 3 B. Elements of a Cause of Action of Negligence 4 1. Notice 4 2. Assumption of Risk 5 Specific Examples of Negligence Claims 6 A. “Slip and Fall” Cases 6 1. Snow and Ice – Natural Accumulation 6 2. Slippery Surfaces 7 3. Defenses 9 B. Off Premises Hazards 12 C. Liability for Violent Crime 12 1. Tavern Keepers Liability for Violent Crime 13 2. Defenses 14 D. Claims Arising from the Wrongful Prevention of Thefts 15 1. False Imprisonment 15 2. Malicious Prosecution and Abuse of Process 16 3. Defamation 17 4. Negligent Hiring, Retention, or Supervision of Employees 18 5. Shopkeeper Immunity 18 6. Food Poisoning 19 E. Construction-Related Accidents 20 Indemnification and Insurance – Procurement Agreement 21 A. Indemnification 21 B. Insurance Procurement Agreements 23 C. Duty to Defend 23 Damages 24 A. Compensatory Damages 24 B. Collateral Source 25 C. Medical Damages (Billed v. Paid) 25 D. Nominal Damages 26 E. Punitive Damages 26 F. Wrongful Death and Survivorship Actions 27 1. Wrongful Death Actions 27 2. Survivorship Actions 28 Dram Shop Actions 28 A. Dram Shop Act 28 Introduction As our communities change and grow, retail stores, restaurants, hotels, and shopping centers have become new social centers.