Distinction Between Assumption of Risk and Contributory Negligence: Host and Guest Relationship (Page 182 Includes Editorial Board)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 22 | Number 1 Symposium: Assumption of Risk Symposium: Insurance Law December 1961 The lP ace of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade Repository Citation John W. Wade, The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La. L. Rev. (1961) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol22/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade* The "doctrine" of assumption of risk is a controversial one, and there is considerable disagreement as to the part which it should play in a negligence case.' On the one hand it has a be- guiling simplicity about it, offering the opportunity of easily disposing of certain cases on a single issue without the need of giving consideration to other, more difficult, issues. On the other hand it overlaps and duplicates certain other doctrines, and its simplicity proves to be misleading because of its failure to point out the policy problems which may be more adequately presented by the other doctrines. Courts disagree as to the scope of the doctrine, some of them confining it to the situation where there is a contractual relation between the parties,2 and others expanding it to any situation in which an action might be brought for negligence.3 Text- writers and commentators commonly criticize the wide applica- tion of the doctrine, and not infrequently suggest that the doc- trine is entirely tautological. -

Torts William E

Louisiana Law Review Volume 32 | Number 2 The Work of the Louisiana Appellate Courts for the 1970-1971 Term: A Symposium February 1972 Private Law: Torts William E. Crawford Louisiana State University Law Center Repository Citation William E. Crawford, Private Law: Torts, 32 La. L. Rev. (1972) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol32/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1972] WORK OF APPELLATE COURTS-1970-1971 213 TORTS William E. Crawford* Contributory Negligence The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeal in Illinois Central Railroad Co. v. Cullen1 refused to hold that the plaintiff rail-, road's leaving a switch unlocked, in violation of its own regula- tion, could amount to contributory negligence in its action for damages against a boy who had thrown the switch open and caused a derailment resulting in the damages suffered by the railroad. The facts show that the defendant came upon the unlocked switch, and after throwing it open, realized that a train was coming and unsuccessfully attempted to return it to its original position. The switch remained open just enough to cause the derailment. The court found that the railroad's own regulation required its personnel to keep switches locked to prevent unauthorized persons from tampering with the switches. and to keep vibrations from opening them. The regulation was admittedly a safety regulation to prevent damage to the plain-. -

Chapter 668 Liability in Tort — Comparative Fault

1 LIABILITY IN TORT — COMPARATIVE FAULT, §668.3 CHAPTER 668 LIABILITY IN TORT — COMPARATIVE FAULT Referred to in §321J.4B, 625.21 668.1 Fault defined. 668.11 Disclosure of expert witnesses 668.2 Party defined. in liability cases involving 668.3 Comparative fault — effect — licensed professionals. payment method. 668.12 Liability for products — defenses. 668.4 Joint and several liability. 668.13 Interest on judgments. Evidence of previous payment or 668.5 Right of contribution. 668.14 future right of payment. 668.6 Enforcement of contribution. 668.14A Recoverable damages for medical 668.7 Effect of release. expenses. 668.8 Tolling of statute. 668.15 Damages resulting from sexual 668.9 Insurance practice. abuse — evidence. 668.10 Governmental exemptions. 668.16 Applicability of this chapter. 668.1 Fault defined. 1. As used in this chapter, “fault” means one or more acts or omissions that are in any measure negligent or reckless toward the person or property of the actor or others, or that subject a person to strict tort liability. The term also includes breach of warranty, unreasonable assumption of risk not constituting an enforceable express consent, misuse of a product for which the defendant otherwise would be liable, and unreasonable failure to avoid an injury or to mitigate damages. 2. The legal requirements of cause in fact and proximate cause apply both to fault as the basis for liability and to contributory fault. 84 Acts, ch 1293, §1 See also §619.17 668.2 Party defined. As used in this chapter, unless otherwise required, “party” means any of the following: 1. -

Assumption of Risk, Waiver, and Release of Liability

Rev. 4/30/2020 ASSUMPTION OF RISK, WAIVER, AND RELEASE OF LIABILITY READ THIS ASSUMPTION OF RISK, WAIVER AND RELEASE OF LIABILITY BEFORE YOU SIGN IT. IT AFFECTS YOUR LEGAL RIGHTS. I, ____________________________ [print student’s name], agree to act in a responsible and safe manner during my participation in the ____________________________ “the Program.” I acknowledge and agree that I must comply with the rules and requirements of the Program, any other applicable University policy, and all applicable local, state, and federal law. I agree to follow the instructions issued by Program directors and staff. I will also abide by signage posted on the University’s campus. I understand that I may be dismissed from the Program for misconduct. I understand that my participation in the Program is voluntary, and I may be exposed to risks and hazards that could result in serious illness, bodily injury, disability, or death. These risks and hazards may include, but are not limited to: (i) vehicular, pedestrian, or other accidents, such as drowning, (ii) storms, floods, fires, earthquakes, and other natural disasters, (iii) infectious diseases or viruses, including but not limited to COVID-19, (iv) limited or inadequate medical care, (v) inadequate design, safety, and maintenance of buildings and public places, (vi) terrorist activities, and (vii) allergic reactions to food, insects, or other allergens. I also understand that during the Program I may use or access educational computer applications, web-based services, or online content that could expose me to certain cyber risks, including but not limited to, cyber predators, data mining, phishing, viruses, malware, data breaches, cyberbullying, exploitation, victimization, cyber stalking, online grooming, reputational loss, brand hijacking, and image replication. -

Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline 1

Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline 1. Introduction 2. The Basis of Tort Law 3. Intentional Torts 4. Negligence 5. Cyber Torts: Defamation Online 6. Strict Liability 7. Product Liability 8. Defenses to Product Liability 9. Tort Law and the Paralegal Chapter Objectives After completing this chapter, you will know: • What a tort is, the purpose of tort law, and the three basic categories of torts. • The four elements of negligence. • What is meant by strict liability and under what circumstances strict liability is applied. • The meaning of strict product liability and the underlying policy for imposing strict product liability. • What defenses can be raised in product liability actions. Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline I. INTRODUCTION A. Torts are wrongful actions. B. The word tort is French for “wrong.” II. THE BASIS OF TORT LAW A. Two notions serve as the basis of all torts. i. Wrongs ii. Compensation B. In a tort action, one person or group brings a personal-injury suit against another person or group to obtain compensation or other relief for the harm suffered. C. Tort suits involve “private” wrongs, distinguishable from criminal actions that involve “public” wrongs. D. The purpose of tort law is to provide remedies for the invasion of various interests. E. There are three broad classifications of torts. i. Intentional Torts ii. Negligence iii. Strict Liability F. The classification of a particular tort depends largely on how the tort occurs (intentionally or unintentionally) and the surrounding circumstances. Intentional Intentions An intentional tort requires only that the tortfeasor, the actor/wrongdoer, intended, or knew with substantial certainty, that certain consequences would result from the action. -

Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory Into Tort Doctrine John L

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 1991 Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine John L. Diamond UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation John L. Diamond, Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine, 52 Ohio St. L.J. 717 (1991). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/103 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Publications UC Hastings College of the Law Library Diamond John Author: John L. Diamond Source: Ohio State Law Journal Citation: 52 Ohio St. L.J. 717 (1991). Title: Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine Originally published in OHIO STATE LAW JOURNAL. This article is reprinted with permission from OHIO STATE LAW JOURNAL and Ohio State University Michael E. Moritz College of Law. Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine JOHN L. DIAMOND* I. INTRODUCTION The confusion generated by the doctrine of assumption of risk' is illustrated by the contradicting responses to the following hypothetical: - 0 1991 John L. Diamond. Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law. B.A., Yale College; J.D., Columbia Law School; Dip. -

Contributory Negligence by Persons with Defective Senses

CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE. 507 qualification is still extant in such state, and that no person can be a juror therein unless he is a freeholder. "This property qualification, in my opinion, is not attached merely as a guard to prevent the juror from being bribed, but for this better reason, that the juror owning property in the vicinage will have a deeper and better interest in ' the life, liberty and pro- perty' of his fellow citizens, and in the honest and proper adminis- tration of justice, than one who owns nothing. The one has a permanent interest in the community in which he resides, and the other has none." WILLIAM S. BRACKETT. Chicago, August 1880. CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE BY PERSONS WITH DEFECTIVE SENSES. THE frequency of cases where suits are brought for damages arising from the negligence of the defendant, brings into unusual prominence the doctrine of contributory negligence. The general doctrine of contributory negligence is well settled, but its applica- tion in many cases seems difficult, and the dicta of judges in adju- dicating upon cases where this defence is introduced, present contradictions which are apparently irreconcilable. Especially is the extent of this doctrine difficult when we come to that class of persons whose senses are defective either by nature or disease. It is the object of this article to treat especially of this class of cases. The law of contributory negligence is stated by Wharton thus: "That a person who, by negligence, has exposed himself to injury, cannot recover damages for the injury thus received, is a principle affirmed by the Roman law and is thus stated by Pomponius: Quod qais ez culpa sua damnum sentit, non intelligitur damnum 8entire. -

Benja Keith Amin Ogd H N. Hylt Den

INCENTIVES TO TAKE CARE UNDER CONTRIBUTORY AND COMPARATIVE FAULT Boston University School of Law Law & Economics Research Paper No. 15-4 (February 13, 2015) Revision of 4-27-2015 Benjamin Ogden Boston University – Department of Economics Keith N. Hylton Boston University School of Laww This paper can be downloaded without charge at: http://www.bu.edu/law/faculty/scholarship/workingpapers/2015.html Incentives to Take Care Under Contributory and Comparative Fault∗ Benjamin Ogden and Keith N. Hyltony 4-27-2015 Abstract Previous literature on contributory versus comparative negligence has shown that they reach equivalent equilibria. These results, however, depend upon a stylized appli- cation of the Hand Formula and an insuciently coarse model of strategic incentives. Taking this into account, we identify a set of cases where care by one agent signicantly increases the benets of care by the other. When such cases obtain under bilateral harm, comparative negligence generates greater incentives for care, but this additional care occurs only when care is not socially optimal. By contrast, under unilateral harm or asymmetric costs of care, contributory negligence creates socially excessive care. There- fore, it is possible to socially rank negligence regimes depending upon the symmetry of potential harm and costs of care. We discuss a potential reform, the Retrospective Neg- ligence Test, that when applied in the case of bilateral harm would make comparative negligence optimal. JEL Classications: K13, K4 Keywords: Comparative Negligence, Contributory Negligence, Fault Regimes, Hand For- mula, Negligence, Optimal Care, Strategic Complimentarity ∗We would like to thank conference and seminar participants at the 41st Annual Conference of the Eastern Economics Association and the Boston University Department of Economics for insightful comments on this work. -

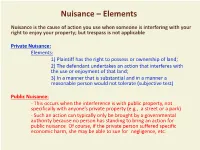

Nuisance – Elements

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

Living Without the Avoidable Consequences Doctrine in Contract Remedies

Living Without the Avoidable Consequences Doctrine in Contract Remedies MICHAEL B. KELLY* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 176 I. A VOIDABLE CONSEQUENCES AS A COROLLARY OF THE EXPECTATION INTEREST . • . 18 I A. Peripheral Aspects of the Avoidable Consequences Doctrine . 18 I I. Affirmative Uses of the Avoidable Consequences Doctrine . I 81 2. Avoided Consequences . I 83 B. Unsuccessfal Efforts To Avoid the Loss . 185 C. The Benefits of Breach of Contract . 187 I. Identifying the Benefits of Breach . 187 2. Quantifying the Benefits . I 90 3. The Effect of Transaction Costs . 201 D. The Benefits in Other Contract Contexts . 205 I. Discharged Employees . 206 a. To what extent does the plaintiff benefit despite reasonable • Professor of Law, University of San Diego School of Law; B.G.S. 1975, University of Michigan; M.A. 1980, University of Illinois at Chicago; J.D. 1983, University of Michigan. Christopher Wonnell' s contributions to this article and to my writings generally deserve particular thanks and recognition. Tom Smith's contributions prevented this paper from floundering. I am also grateful for the contributions of Larry Alexander, Gail Heriot, Michael Rappaport, Emily Sherwin, Kristine Strachan, Paul Wohlmuth, Fred Zacharias, and many others who encouraged or hounded me during this project. The research assistance of Geoffrey Morrison, Ronald Webb, John Doherty, and David Boyd and financial support from the University of San Diego also contributed to the successful completion of this article. 175 but unsuccessful efforts to minimize the loss? . 206 b. Why limit the value of the benefit to the amount of loss that could have been avoided by reasonable efforts? . -

The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability

Michigan Law Review Volume 64 Issue 7 1966 Products Liability--The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability John A. Sebert Jr. University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation John A. Sebert Jr., Products Liability--The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability, 64 MICH. L. REV. 1350 (1966). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol64/iss7/10 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS Products Liability-The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability The advances in recent years in the field of products liability have probably outshone, in both number a~d significance, the prog ress during the same period in most other areas of the law. These rapid developments in the law of consumer protection have been marked by a consistent tendency to expand the liability· of manu facturers, retailers, and other members of the distributive chain for physical and economic harm caused by defective merchandise made available to the public. Some of the most notable progress has been made in the law of tort liability. A number of courts have adopted the principle that a manufacturer, retailer, or other seller1 of goods is answerable in tort to any user of his product who suffers injuries attributable to a defect in the merchandise, despite the seller's exer cise of reasonable care in dealing with the product and irrespective of the fact that no contractual relationship has ever existed between the seller and the victim.2 This doctrine of strict tort liability, orig inally enunciated by the California Supreme Court in Greenman v. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of NEBRASKA E3 BIOFUELS-MEAD, LLC, Plaintiff(S), V. SKINNER TANK COMPANY;

8:06-cv-00706-JFB-FG3 Doc # 232 Filed: 01/30/14 Page 1 of 11 - Page ID # <pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEBRASKA E3 BIOFUELS-MEAD, LLC, Plaintiff(s), 8:06CV706 v. SKINNER TANK COMPANY; MEMORANDUM AND ORDER Defendant/Third-Party Plaintiff, v. DILLING MECHANICAL CONTRACTORS, INC. Third-Party Defendant. This matter is before the court on a motion for partial summary judgment filed by defendant/third-party plaintiff Skinner Tank Company (“Skinner”), Filing No. 162. This is an action for breach of contract, fraud, and gross negligence in connection with an ethanol plant construction project in Mead, Nebraska.1 The plaintiffs, E Biofuels-Mead, LLC and E3 Biofuels-Mead, LLC (hereinafter, collectively, “E3”), entered into a contract with defendant Skinner for the purchase, design, fabrication, construction and installation of several tanks to be used in an Integrated Solid Waste and Bio-Fuels Facility (the “Project”) that retrieves usable energy from cattle waste. Jurisdiction is premised on 28 U.S.C. § 1332, diversity of citizenship. 1 The action also involves a counterclaim against E3 and third-party claim against Dilling Construction, the management firm hired by E3 for the project, for tortious interference with a contract, negligence, indemnification and contribution. 8:06-cv-00706-JFB-FG3 Doc # 232 Filed: 01/30/14 Page 2 of 11 - Page ID # <pageID> Skinner moves for a summary judgment of dismissal on the plaintiff’s claims of fraud and gross negligence, asserting that those claims are barred under the economic loss doctrine. Further, it argues that E3 has failed to plead fraud with particularity under Fed.