Tom Wolfe and the Rise of Donald Trump: a Review of Wolfe's Writings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mechanic the Secret World of the F1 Pitlane Marc 'Elvis' Priestley

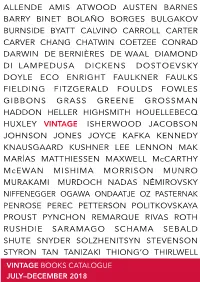

ALLENDE AMIS ATWOOD AUSTEN BARNES BARRY BINET BOLAÑO BORGES BULGAKOV BURNSIDE BYATT CALVINO CARROLL CARTER CARVER CHANG CHATWIN COETZEE CONRAD DARWIN DE BERNIÈRES DE WAAL DIAMOND DI LAMPEDUSA DICKENS DOSTOEVSKY DOYLE ECO ENRIGHT FAULKNER FAULKS FIELDING FITZGERALD FOULDS FOWLES GIBBONS GRASS GREENE GROSSMAN HADDON HELLER HIGHSMITH HOUELLEBECQ HUXLEY ISHERWOOD JACOBSON JOHNSON JONES JOYCE KAFKA KENNEDY KNAUSGAARD KUSHNER LEE LENNON MAK MARÍAS MATTHIESSEN MAXWELL McCARTHY McEWAN MISHIMA MORRISON MUNRO MURAKAMI MURDOCH NADAS NÉMIROVSKY NIFFENEGGER OGAWA ONDAATJE OZ PASTERNAK PENROSE PEREC PETTERSON POLITKOVSKAYA PROUST PYNCHON REMARQUE RIVAS ROTH RUSHDIE SARAMAGO SCHAMA SEBALD SHUTE SNYDER SOLZHENITSYN STEVENSON STYRON TAN TANIZAKI THIONG’O THIRLWELL TVINTAGEHORPE BOOKS THU CATALOGUEBRON TOLSTOY TREMAIN TJULY–DECEMBERYLER VARGAS 2018 VONNEGUT WARHOL WELSH WESLEY WHEELER WIGGINS WILLIAMS WINTERSON WOLFE WOOLF WYLD YATES ZOLA ALLENDE AMIS ATWOOD AUSTEN BARNES BARRY BINET BOLAÑO BORGES BULGAKOV BURNSIDE BYATT CALVINO CARROLL CARTER CARVER CHANG CHATWIN COETZEE CONRAD DARWIN DE BERNIÈRES DE WAAL DIAMOND DI LAMPEDUSA DICKENS DOSTOEVSKY DOYLE ECO ENRIGHT FAULKNER FAULKS FIELDING FITZGERALD FOULDS FOWLES GIBBONS GRASS GREENE GROSSMAN HADDON HELLER HIGHSMITH HOUELLEBECQ HUXLEY ISHERWOOD JACOBSON JOHNSON JONES JOYCE KAFKA KENNEDY KNAUSGAARD KUSHNER LEE LENNON MAK MARÍAS MATTHIESSEN MAXWELL McCARTHY McEWAN MISHIMA MORRISON MUNRO MURAKAMI MURDOCH NADAS NÉMIROVSKY NIFFENEGGER OGAWA ONDAATJE OZ PASTERNAK PENROSE PEREC PETTERSON POLITKOVSKAYA PROUST PYNCHON -

John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba

LIKE RABBITS Welcome to TimesPeople TimesPeople Lets You Share and Discover the Bes Get Started HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS Books WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYL ART & DESIGN BOOKS Sunday Book Review Best Sellers First Chapters DANCE MOVIES MUSIC John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba By CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT Sig Published: January 28, 2009 wee SIGN IN TO den RECOMMEND John Updike, the kaleidoscopically gifted writer whose quartet of Cha Rabbit novels highlighted a body of fiction, verse, essays and criticism COMMENTS so vast, protean and lyrical as to place him in the first rank of E-MAIL Ads by Go American authors, died on Tuesday in Danvers, Mass. He was 76 and SEND TO PHONE Emmetsb Commerci lived in Beverly Farms, Mass. PRINT www.Emme REPRINTS U.S. Trus For A New SHARE Us Directly USTrust.Ba Lanco Hi 3BHK, 4BH Living! www.lancoh MOST POPUL E-MAILED 1 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. All rights reserved. 7/9/2009 10:55 PM LIKE RABBITS 1. Month Dignit 2. Well: 3. GLOB 4. IPhon 5. Maure 6. State o One B 7. Gail C 8. A Run Meani 9. Happy 10. Books W. Earl Snyder Natur John Updike in the early 1960s, in a photograph from his publisher for the release of “Pigeon Feathers.” More Go to Comp Photos » Multimedia John Updike Dies at 76 A star ALSO IN BU The dark Who is th ADVERTISEM John Updike: A Life in Letters Related An Appraisal: A Relentless Updike Mapped America’s Mysteries (January 28, 2009) 2 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. -

Author Tom Wolfe

University Events Office presents lecture by "The Right Stuff" author Tom Wolfe May 8, 1986 Tom Wolfe, the man who put La Jolla's Windansea on the map in 1968 when his "Pump House Gang" chronicled the life of the surfers who hung out around the beach's pump house, will speak on "The Novel in an Age of Nonfiction," at 8 p.m. Thursday, May 22, in the University of California, San Diego's Main Gymnasium. Wolfe's book, "The Right Stuff," published in 1979, is a pithy view of the first astronauts and the early days of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's space program. "The Right Stuff" became a runaway best seller and won the American Book Award for general nonfiction. After his first book, "The Kandy Kolored Tangerine Flake Streamline Baby," Wolfe wrote "The Electric Kool- Aid Acid Test," a tale about LSD and a group of people who drove around the country in a multicolored bus calling themselves the Merry Pranksters; and "The Pump House Gang," all of which became undergraduate student bibles. In 1970, Wolfe published "Radical Chic and Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers," a devastatingly funny portrayal of American political stances and social styles. In 1975, he published "The Painted Word," a humorous look at the world of modern art, which received a special citation from the National Sculpture Society. "Mauve Gloves and Madmen, Clutter and Vine," is a collection of essays which was published in 1976. In 1980, Wolfe published his first collection of drawings, entitled, "In Our Time." In 1981, he took a distinctive look at contemporary architecture in his book, "From Bauhaus to Our House." This work was followed by "The Purple Decades: A Reader." Wolfe grew up in Richmond, Virginia. -

MY PASSAGES Traces the Path of Gail Sheehy's Life, I

DARING: My Passages By Gail Sheehy Discussion Questions: 1. While DARING: MY PASSAGES traces the path of Gail Sheehy’s life, it also is a fascinating insider’s account of the ways in which journalism has evolved from the 1960s to the present day. How different is the media world today from the world she describes? What changes have come about for the better? Has anything gotten worse? If you were a journalist and could pick any decade to “fall into” career-wise, which one would you choose? What stories or moments in history would you most like to cover (or have covered)? 2. As a journalist, Gail Sheehy was —and still is — fearless. “Why couldn’t a woman write about the worlds that men wrote about?” she asked herself early on and throughout her career. Do you think you would’ve had the guts to be a female reporter during a time when journalism was dominated by men? What qualities do you think she and other pioneers like Gloria Steinem possess that enabled them to court long-standing success despite the risks involved? 3. Though Sheehy enjoyed a short first marriage and a long-standing on-again, off- again relationship with visionary journalist Clay Felker that later culminated in marriage, she was a single mother and thriving career woman for much of her adult life. Throughout DARING: MY PASSAGES, she writes about her attempts to balance motherhood with a successful career. What do you make of the way she approached this struggle? How are the challenges she faced then different from those working mothers face in today’s society? If you were in Sheehy’s shoes, do you think you would have juggled career and motherhood as she did, or would you have given up one for the other? 4. -

Download the Painted Word Pdf Book by Tom Wolfe

Download The Painted Word pdf ebook by Tom Wolfe You're readind a review The Painted Word book. To get able to download The Painted Word you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite ebooks in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this ebook on an database site. Ebook File Details: Original title: The Painted Word 112 pages Publisher: Picador; First edition (October 14, 2008) Language: English ISBN-10: 9780312427580 ISBN-13: 978-0312427580 ASIN: 0312427581 Product Dimensions:5.4 x 0.4 x 8.2 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 7111 kB Description: Americas nerviest journalist (Newsweek) trains his satirical eye on Modern Art in this masterpiece (The Washington Post)Wolfes style has never been more dazzling, his wit never more keen. He addresses the scope of Modern Art, from its founding days as Abstract Expressionism through its transformations to Pop, Op, Minimal, and Conceptual. The Painted... Review: If you have ever been confused, amused, or just plain confounded by abstract art, this book will make it very clear what its all about and what its not! Wolf described the forces, real and imagined, that brought this art movement to the fore. On the way you will smile and laugh at the goings on in the NY art world of the 50s and 60s. When you are... Book File Tags: tom wolfe pdf, modern art pdf, painted word pdf, art world pdf, new york pdf, abstract expressionism pdf, jackson pollock pdf, clement greenberg pdf, harold rosenberg pdf, contemporary art pdf, years ago pdf, bauhaus to our house pdf, pop art pdf, greenberg and rosenberg pdf, read this book pdf, leo steinberg pdf, art scene pdf, art history pdf, jasper johns pdf, art theory The Painted Word pdf ebook by Tom Wolfe in Arts and Photography Arts and Photography pdf books The Painted Word painted the word pdf the painted word fb2 painted the word ebook word painted the book The Painted Word The only bad thing I hate is how quickly it was over. -

The Depiction of Law in the Bonfire of the Vanities

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1988 The Depiction of Law in the Bonfire of the Vanities Richard A. Posner Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Posner, "The Depiction of Law in the Bonfire of the Vanities," 98 Yale Law Journal 1653 (1988). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Depiction of Law in The Bonfire of the Vanities Richard A. Posnert Tom Wolfe's best-selling novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities, first pub- lished in 1987 and recently reissued in paperback, illustrates an aspect of the interaction between law and literature not discussed in my recent book on the law and literature movement, and indeed rather neglected (but per- haps benignly) by the movement as a whole. This is the depiction of law in popular literature.1 The popularity of Wolfe's novel and the salience of law in it make it a natural subject for consideration in a symposium on the treatment of law in popular culture. And if, as I shall argue, The Bonfire of the Vanities is not an especially rewarding subject for the study of law in popular culture after all, this may serve as a warning against unwarranted expectations concerning how much we can learn about law from its representation in popular culture, or about popular culture from its representation of law, or even about popular understanding of law. -

Spitzer's Aides Find It Difficult to Start Anew

CNYB 07-07-08 A 1 7/3/2008 7:17 PM Page 1 SPECIAL SECTION NBA BETS 2008 ON OLYMPICS; ALL-STAR GAME HITS HOME RUN IN NEW YORK ® PAGE 3 AN EASY-TO-USE GUIDE TO THE VOL. XXIV, NO. 27 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM JULY 7-13, 2008 PRICE: $3.00 STATISTICS Egos keep THAT MATTER THIS Spitzer’s aides YEAR IN NEW YORK newspaper PAGES 9-43 find it difficult presses INCLUDING: ECONOMY rolling FINANCIAL to start anew HEALTH CARE Taking time off to decompress Local moguls spend REAL ESTATE millions even as TOURISM life. Paul Francis, whose last day business turns south & MORE BY ERIK ENGQUIST as director of operations will be July 11, plans to take his time three months after Eliot before embarking on his next BY MATTHEW FLAMM Spitzer’s stunning demise left endeavor, which he expects will them rudderless,many members be in the private sector. Senior ap images across the country,the newspa- of the ex-governor’s inner circle adviser Lloyd Constantine,who per industry is going through ar- have yet to restart their careers. followed Mr. Spitzer to Albany TEAM SPITZER: guably the darkest period in its A few from the brain trust that and bought a house there, has THEN AND NOW history, with publishers slashing once seemed destined to reshape yet to return to his Manhattan newsroom staff and giants like Tri- the state have moved on to oth- law firm, Constantine Cannon. RICH BAUM bune Co.standing on shaky ground. AT DEADLINE er jobs, but others are taking Working for the hard-driv- WAS The governor’s Things are different in New time off to decompress from the ing Mr.Spitzer,“you really don’t secretary York. -

Understanding Mens Passages: Discovering the New Map of Mens Lives Pdf, Epub, Ebook

UNDERSTANDING MENS PASSAGES: DISCOVERING THE NEW MAP OF MENS LIVES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gail Sheehy | 298 pages | 04 May 1999 | Random House USA Inc | 9780345406903 | English | New York, United States Understanding Mens Passages: Discovering the New Map of Mens Lives PDF Book Roger Huddleston rated it did not like it Apr 20, Buy at Local Store Enter your zip code below to purchase from an indie close to you. May 04, Lois Duncan rated it it was ok. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Maybe that information wasn't available then. Effective early intervention is critical in stopping low and moderate-risk cases of family violence escalating into high-risk situations. The older knowledge we have does not fit with our new realities and our experiences of the world. Willis , James B. The book is broken up into 'this is what you're going through' and 'this My father passed recently and I found myself in a strange, new land where I wasn't sure where I was going and why I didn't know where I was going. Popular author of coloring books for adults and teens, certified cognitive therapist Bella Stitt created this book for relieving stress from everyday life. Sheehy is also a political journalist and contributing editor to Vanity Fair. Nov 10, Sylvia rated it really liked it. Apr 15, Skyqueen rated it really liked it. Among her twelve books is the huge international bestseller that broke the taboo around menopause, The Silent Passage. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. -

When Victims Rule

1 24 JEWISH INFLUENCE IN THE MASS MEDIA, Part II In 1985 Laurence Tisch, Chairman of the Board of New York University, former President of the Greater New York United Jewish Appeal, an active supporter of Israel, and a man of many other roles, started buying stock in the CBStelevision network through his company, the Loews Corporation. The Tisch family, worth an estimated 4 billion dollars, has major interests in hotels, an insurance company, Bulova, movie theatres, and Loliards, the nation's fourth largest tobacco company (Kent, Newport, True cigarettes). Brother Andrew Tisch has served as a Vice-President for the UJA-Federation, and as a member of the United Jewish Appeal national youth leadership cabinet, the American Jewish Committee, and the American Israel Political Action Committee, among other Jewish organizations. By September of 1986 Tisch's company owned 25% of the stock of CBS and he became the company's president. And Tisch -- now the most powerful man at CBS -- had strong feelings about television, Jews, and Israel. The CBS news department began to live in fear of being compromised by their boss -- overtly, or, more likely, by intimidation towards self-censorship -- concerning these issues. "There have been rumors in New York for years," says J. J. Goldberg, "that Tisch took over CBS in 1986 at least partly out of a desire to do something about media bias against Israel." [GOLDBERG, p. 297] The powerful President of a major American television network dare not publicize his own active bias in favor of another country, of course. That would look bad, going against the grain of the democratic traditions, free speech, and a presumed "fair" mass media. -

The State of Art Criticism

Page 1 The State of Art Criticism Art criticism is spurned by universities, but widely produced and read. It is seldom theorized, and its history has hardly been investigated. The State of Art Criticism presents an international conversation among art historians and critics that considers the relation between criticism and art history, and poses the question of whether criticism may become a university subject. Participants include Dave Hickey, James Panero, Stephen Melville, Lynne Cook, Michael Newman, Whitney Davis, Irit Rogoff, Guy Brett, and Boris Groys. James Elkins is E.C. Chadbourne Chair in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His many books include Pictures and Tears, How to Use Your Eyes, and What Painting Is, all published by Routledge. Michael Newman teaches in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and is Professor of Art Writing at Goldsmiths College in the University of London. His publications include the books Richard Prince: Untitled (couple) and Jeff Wall, and he is co-editor with Jon Bird of Rewriting Conceptual Art. 08:52:27:10:07 Page 1 Page 2 The Art Seminar Volume 1 Art History versus Aesthetics Volume 2 Photography Theory Volume 3 Is Art History Global? Volume 4 The State of Art Criticism Volume 5 The Renaissance Volume 6 Landscape Theory Volume 7 Re-Enchantment Sponsored by the University College Cork, Ireland; the Burren College of Art, Ballyvaughan, Ireland; and the School of the Art Institute, Chicago. 08:52:27:10:07 Page 2 Page 3 The State of Art Criticism EDITED BY JAMES ELKINS AND MICHAEL NEWMAN 08:52:27:10:07 Page 3 Page 4 First published 2008 by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2007. -

The Painted Word

The Painted Word copyright © 1975 by Tom Wolfe PEOPLE DON’T READ THE MORNING NEWSPAPER, Marshall McLuhan once said, they slip into it like a warm bath. Too true, Marshall! Imagine being in New York City on the morning of Sunday, April 28, 1974, like I was, slipping into that great public bath, that vat, that spa, that, regional physiotherapy tank, that White Sulphur Springs, that Marienbad, that Ganges, that River Jordan for a million souls which is the Sunday New York Times. Soon I was submerged, weightless, suspended in the tepid depths of the thing, in Arts & Leisure, Section 2, page 19, in a state of perfect sensory deprivation, when all at once an extraordinary thing happened: I noticed something! Yet another clam-broth-colored current had begun to roll over me, as warm and predictable as the Gulf Stream ... a review, it was, by the Time’s dean of the arts, Hilton Kramer, of an exhibition at Yale University of “Seven Realists,” seven realistic painters . when I was jerked alert by the following: “Realism does not lack its partisans, but it does rather conspicuously lack a persuasive theory. And given the nature of our intellectual commerce with works of art, to lack a persuasive theory is to lack something crucial—the 1 means by which our experience of individual works is joined to our understanding of the values they signify.” Now, you may say, My God, man! You woke up over that? You forsook your blissful coma over a mere swell in the sea of words? But I knew what I was looking at. -

Naturalism, the New Journalism, and the Tradition of the Modern American Fact-Based Homicide Novel

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800!521-0600 Order Number 9406702 Naturalism, the new journalism, and the tradition of the modern American fact-based homicide novel Whited, Lana Ann, Ph.D.