Lyall Bay Coastal Remediation D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wellington City Empowering and Amendment

1 3. .:f Mr. Wright. WELLINGTON CITY EMPOWERING AND AMENDMENT. [LOCAL BILL._] ANALYSIS. Title. 1. Short Title. 10. Extension of time within which Council's 2. Definitions. authority to borrow moneys conferred by 3. Council may appropriate land usable for any ratepayers may be exercised. public work to any other public work. 11. Council authorized to permit encroachment of 4, Power to impose construction of drains on ' Show Building on right-of-way adjacent to 01'1-ners subdividing land. Westland Road. 5. Extension of time for completion of Evans 12. Amendment of paragraph (e) of section 6 of Bay reclamation. the Wellington City Empowering and 6. Power to close portion of Evans Bay Road and Amendrnent Act, 1924. vest same in the Hataitai Land Co., Ltd. 13. Alternative method of disposal of proceeds of 7. Declaring certain ways to be public streets. sale of the Mangahao Endowment of the 8. Special orders relating to loans to be Corporation. unassailable. 14. Power to transfer portion of Keringa Street 9. Council authorized to establish air-port at and portion of Town Belt to Fire Board. Lyall Bay, and to make by-laws for the Schedules. control thereof, and to raise money for mich piirpose. A BILL INTITULED AN AcT to authorize the Corporation to alter the Purpose of Land Title. appropriated to Public Works ; to require Owners subdividing Lands to construct Drains ; to extend the Time for the Construction 5 of the City's Evans Bay Reclamation ; to close Portion of Evans Bay Road and vest Same in the Hataitai Land Company, Limited; to declare -

NIWA CLIENT REPORT No: HAM2015-079 Report Date: March 2016 NIWA Project: WIA15301

Technical Report 15 National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd (NIWA) – Coastal Processes Assessment Wellington International Airport Runway Extension Coastal Processes Assessment Prepared for Wellington International Airport Ltd March 2016 Prepared by: R.G. Bell For any information regarding this report please contact: Rob Bell Programme Leader: Hazards & Risk Coastal & Estuarine Processes +64-7-856 1742 [email protected] National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd PO Box 11115 Hamilton 3251 Phone +64 7 856 7026 NIWA CLIENT REPORT No: HAM2015-079 Report date: March 2016 NIWA Project: WIA15301 Quality Assurance Statement Reviewed by: Craig Stevens Formatting checked by: Alison Bartley Approved for release by: Andrew Laing Image of Wellington International Airport and Lyall Bay in southerly sea/swell on 20 July 2015. North is due left of image. [Source: DigitalGlobe/Google Earth] © All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the copyright owner(s). Such permission is only to be given in accordance with the terms of the client’s contract with NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. Whilst NIWA has used all reasonable endeavours to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate, NIWA does not give any express or implied warranty as to the completeness of the information contained herein, or that it will be suitable for any purpose(s) other than those specifically contemplated during the Project or agreed by NIWA and the Client. Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................ -

Resource Consent Applications Received 1 February 2021 – 13 February 2021

Resource Consent applications received 1 February 2021 – 13 February 2021 You can sign up for a web alert at the bottom of Wellington.govt.nz to receive an email when this is updated. A Service Request (SR) number is the individual identification we give each Resource Consent application when lodged with Wellington City Council. If you contact us about any specific consent below, please quote this number. For More information on these consents please phone Customer Services on (04) 801 3590 or email Suburb Address Date SR No. Description Brooklyn 8 Monteith Grove 3/02/2021 483187 Land Use: New dwelling & associated earthworks Brooklyn 328 Hawkins Hill Road 11/02/2021 483759 Land Use: New dwelling on existing dwelling Churton Park 23 Lakewood Avenue 1/02/2021 482926 Boundary Activity: New deck Churton Park 14 Hattersley Grove 9/02/2021 483528 Land Use: earthworks Churton Park 15 Hattersley Grove 9/02/2021 483532 Land Use: New dwelling Hataitai 4 Rakau Road 9/02/2021 483529 Land Use: Additions and alterations to existing dwelling Hataitai 68 Kainui Road 11/02/2021 483753 Land Use: Additions and alterations Hataitai 45 Kainui Road 12/02/2021 483870 Land Use: New dwelling Hataitai 27 Alexandra Road 10/02/2021 483650 Change of Conditions: Relating to SR460047 Houghton Bay 13 Twomey Grove 9/02/2021 483536 Boundary Activity: New dwelling Houghton Bay 7 Ara Haewai 1/02/2021 482917 Land Use: New dwelling Island Bay 11 Erica Pabst Way 9/02/2021 483530 Change of Conditions: Relating to SR365583 Johnsonville 17 Meadowcroft Grove 9/02/2021 483589 Boundary -

Methodist Church of New Zealand Archives Wellington District Baptism Registers

Methodist Church of New Zealand Archives Wellington District Baptism Registers Holdings at October 2013 For more information, please contact: The Archivist Methodist Church of New Zealand Archives PO Box 931 Christchurch New Zealand 8140 Phone 03 366 6049 Email: [email protected] Website: www.methodist.org.nz The Methodist Church of New Zealand Archives in Christchurch is the approved repository for Methodist baptism registers once completed by parishes. They are part of parish and church records held in the Methodist Archives. Registers can date from the first Wesleyan missionaries’ time in New Zealand during the 1830s, through to the present day. They include all branches of Methodism in New Zealand: Primitive Methodist, Wesleyan, United Free Methodist, and Bible Christian. Some registers, particularly those still in use, are held by parishes. Details of how to contact parishes are on the Methodist Church website www.methodist.org.nz In the case of union or combined parishes, registers containing Methodist baptisms may be held by other repositories such as the Presbyterian Archives and Anglican Archives. The format of baptism registers varied over the years. Early registers often only contained the name of the person being baptised, the date of baptism, the district they lived in and the name of the minister performing the baptism. 1 Methodist Church of New Zealand Archives Auckland District Baptism Registers List updated October 2013 Later on, when standard baptism registers were printed and distributed by the Methodist Church, more information was added, such as birth date, names of parents, their address and the parish or circuit in which the baptism was taking place. -

Wellington Walks – Ara Rēhia O Pōneke Is Your Guide to Some of the Short Walks, Loop Walks and Walkways in Our City

Detail map: Te Ahumairangi (Tinakori Hill) Detail map: Mount Victoria (Matairangi) Tracks are good quality but can be steep in places. Tracks are good quality but can be steep in places. ade North North Wellington Otari-Wilton’ss BushBush OrientalOriental ParadePar W ADESTOWN WeldWeld Street Street Wade Street Oriental Bay Walks Grass St. WILTON Oriental Parade O RIEN T A L B A Y Ara Rēhia o Pōneke Northern Walkway PalliserPalliser Rd.Rd. Skyline Walkway To City ROSENEATH Majoribanks Street City to Sea Walkway LookoutLookout Rd.Rd. Te Ara o Ngā Tūpuna Mount Victoria Lookout MOUNT (Tangi(Tangi TeTe Keo)Keo) Te Ahumairangi Hill GrantGrant RoadRoad VICT ORIA Lookout PoplarPoplar GGroroveve PiriePirie St.St. THORNDON AlexandraAlexandra RoadRoad Hobbit Hideaway The Beehive Film Location TinakoriTinakori RoadRoad & ParliameParliamentnt rangi Kaupapa RoadStSt Mary’sMary’s StreetStreet OOrangi Kaupapa Road buildingsbuildings WaitoaWaitoa Rd.Rd. HataitaiHataitai RoadHRoadATAITAI Welellingtonlington BotanicBotanic GardenGarden A B Southern Walkway Loop walks City to Sea Walkway Matairangi Nature Trail Lookout Walkway Northern Walkway Other tracks Southern Walkway Hataitai to City Walkway 00 130130 260260 520520 Te Ahumairangi metresmetres Be prepared For more information Your safety is your responsibility. Before you go, Find our handy webmap to navigate on your mobile at remember these five simple rules: wcc.govt.nz/trailmaps. This map is available in English and Te Reo Māori. 1. Plan your trip. Our tracks are clearly marked but it’s a good idea to check our website for maps and track details. Find detailed track descriptions, maps and the Welly Walks app at wcc.govt.nz/walks 2. Tell someone where you’re going. -

NIWA – Technical Report on Coastal Hydrodynamics and Sediment Processes in Lyall Bay

Technical Report 17 NIWA – Technical Report on Coastal Hydrodynamics and Sediment Processes in Lyall Bay Wellington Airport Runway Extension Technical Report on Coastal Hydrodynamics and Sediment Processes in Lyall Bay Prepared for Wellington International Airport Ltd March 2015 (updated March 2016) Prepared by: Mark Pritchard Glen Reeve Richard Gorman Iain MacDonald Rob Bell For any information regarding this report please contact: Rob Bell Programme Leader: Hazards & Risk Coastal & Estuarine Processes +64-7-856 1742 [email protected] National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd PO Box 11115 Hamilton 3251 Phone +64 7 856 7026 NIWA CLIENT REPORT No: HAM2015-003 Report date: March 2015 (updated March 2016) NIWA Project: WIA15301 Quality Assurance Statement Reviewed by: Dr S. Stephens Formatting checked by: A. Bartley Approved for release by: Dr A. Laing Front page photo: Lyall Bay aerial photograph (2013-14 LINZ aerial photography series). © All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the copyright owner(s). Such permission is only to be given in accordance with the terms of the client’s contract with NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. Whilst NIWA has used all reasonable endeavours to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate, NIWA does not give any express or implied warranty as to the completeness of the information contained herein, or that it will be suitable for any purpose(s) other than those specifically contemplated during the Project or agreed by NIWA and the Client. -

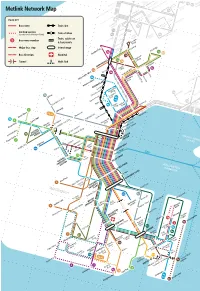

Metlink Network

1 A B 2 KAP IS Otaki Beach LA IT 70 N I D C Otaki Town 3 Waikanae Beach 77 Waikanae Golf Course Kennedy PNL Park Palmerston North A North Beach Shannon Waikanae Pool 1 Levin Woodlands D Manly Street Kena Kena Parklands Otaki Railway 71 7 7 7 5 Waitohu School ,7 72 Kotuku Park 7 Te Horo Paraparaumu Beach Peka Peka Freemans Road Paraparaumu College B 7 1 Golf Road 73 Mazengarb Road Raumati WAIKANAE Beach Kapiti E 7 2 Arawhata Village Road 2 C 74 MA Raumati Coastlands Kapiti Health 70 IS Otaki Beach LA N South Kapiti Centre A N College Kapiti Coast D Otaki Town PARAPARAUMU KAP IS I Metlink Network Map PPL LA TI Palmerston North N PNL D D Shannon F 77 Waikanae Beach Waikanae Golf Course Levin YOUR KEY Waitohu School Kennedy Paekakariki Park Waikanae Pool Otaki Railway ro 3 Woodlands Te Ho Freemans Road Bus route Parklands E 69 77 Muri North Beach 75 Titahi Bay ,77 Limited service Pikarere Street 68 Peka Peka (less than hourly, Monday to Friday) Titahi Bay Beach Pukerua Bay Kena Kena Titahi Bay Shops G Kotuku Park Gloaming Hill PPL Bus route number Manly Street71 72 WAIKANAE Paraparaumu College 7 Takapuwahia 1 Plimmerton Paraparaumu Major bus stop Train line Porirua Beach Mazengarb Road F 60 Golf Road Elsdon Mana Bus direction 73 Train station PAREMATA Arawhata Mega Centre Raumati Kapiti Road Beach 72 Kapiti Health 8 Village Train, cable car 6 8 Centre Tunnel 6 Kapiti Coast Porirua City Cultural Centre 9 6 5 6 7 & ferry route 6 H Coastlands Interchange Porirua City Centre 74 G Kapiti Police Raumati College PARAPARAUMU College Papakowhai South -

Lyall Bay/Rongotai HIGH FREQUENCY & PEAK ONLY ROUTES

Effective from 25 October 2020 Lyall Bay/Rongotai HIGH FREQUENCY & PEAK ONLY ROUTES 3 36 Wellington Station Massey University Wellington Hospital Thanks for travelling with Metlink. Kilbirnie Connect with Metlink for timetables Rongotai and information about bus, train and ferry services in the Wellington region. Lyall Bay metlink.org.nz 0800 801 700 [email protected] @metlinkwgtn /metlinkonourway Printed with mineral-oil-free, soy-based vegetable inks on paper produced using Forestry Stewardship Council® (FSC®) certified mixed-source pulp that complies with environmentally responsible practices and principles. Please recycle and reuse if possible. Before taking a printed timetable, check our timetables online or use the Metlink commuter app. GW/PT-G-20/53 October 2020 T i n a d k a o o t r S R i i r R e o o k v a a a r in d Hill Stre g e T t l O Aitken S t u f M y LYALL BAY/RONGOTAIf a R u a Q m o p o Bo rl WELLINGTON w e en t Stre a 3 36 et W STATION B un ny St NORTHLAND Stout Street LAMBTON Glasgow Wharf Inter-Island Wharf Waterloo Wharf Featherston Street Wellington Panama St Cable Car Customhouse Quay d R a c n a m WELLINGTON a l a S CENTRAL Lambton Harbour G J l a e e d s r c R g v e a o r o r o r i G KELBURN w s e n to T Q l S r t e u e a r a Queens C h d e a d y a T r Ro e Pa t Wharf tal ien Chaffers Oriental Bay Or d C Marina T a a h o b e le R D S n Little Karaka Bay i C xo t o n re t S e r tr e f e t a et s r c e G n t ORIENTAL Balaena Bay Co BAY ARO VALLEY urt TE ARO ena ROSENEATH y P COURTENAY P lace Hawker St a t lli e -

Kilbirnie Community Emergency Hub Guide

REVIEWED JULY 2018 Kilbirnie Community Emergency Hub Guide This Hub is a place for the community to coordinate your efforts to help each other during and after a disaster. Objectives of the Community Emergency Hub are to: › Provide information so that your community knows how to help each other and stay safe. › Understand what is happening. Wellington Region › Solve problems using what your community has available. Emergency Managment Office › Provide a safe gathering place for members of the Logo Specificationscommunity to support one another. Single colour reproduction WELLINGTON REGION Whenever possible, the logo should be reproduced EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT in full colour. When producing the logo in one colour, OFFICE the Wellington Region Emergency Managment may be in either black or white. WELLINGTON REGION Community Emergency Hub Guide a EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OFFICE Colour reproduction It is preferred that the logo appear in it PMS colours. When this is not possible, the logo should be printed using the specified process colours. WELLINGTON REGION EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OFFICE PANTONE PMS 294 PMS Process Yellow WELLINGTON REGION EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OFFICE PROCESS C100%, M58%, Y0%, K21% C0%, M0%, Y100%, K0% Typeface and minimum size restrictions The typeface for the logo cannot be altered in any way. The minimum size for reproduction of the logo is 40mm wide. It is important that the proportions of 40mm the logo remain at all times. Provision of files All required logo files will be provided by WREMO. Available file formats include .eps, .jpeg and .png About this guide This guide provides information to help you set up and run the Community Emergency Hub. -

Dads Embracing School Life

Police find Pupil cycles forgotten 1600km for treasures P3 playground P6 WellingtonianThe Thursday, December 1, 2016 thewellingtonian.co.nz Members of the Lyall Bay Dads Group manning the barbecue at the free fair event. From right: Sloane McPhee, Darrell Doig, Dan Perry and Steve Boggs. EMMA DUNLOP-BENNETT Dads embracing school life RUBY MACANDREW school mums ‘‘seemed to know lish a club and host fortnightly ment of all the people in the com- and Chait said he fielded several each other and be quite well- get-togethers. munity - dads included. We inquiries from other dads keen to A community event has helped connected’’, but the same couldn’t ‘‘It’s about getting the dads wanted to tap into that and join join the group and help out the shine a light on the hard work a be said for the dads. involved and connected to learn the dots really.’’ school. group of dads from Lyall Bay ‘‘There were very few dads more about who your neighbours The group had since expanded ‘‘This is not a fundraiser or School has been doing to be more around the school and the ones are and through that become their offerings, including the way to make money – our involved. that did come were all heads more involved in the school.’’ establishment of a touch team motivations in doing this are only After 18 months the ranks of down, drop their kids off and go. From the initial meeting, inter- with 16 members. to bring our local community the Lyall Bay Dads Club have ‘‘It occurred to us that a lot of est in the collective snowballed, An example of the way the closer together.’’ been growing exponentially, and the dads didn’t get to do drop-offs which Chait said was a testament group gets involved is the large- For now, Chait planned to keep they have become a mainstay in that often and the ones that did to the need for dads to be scale fair they recently organised the group’s membership exclus- the school community. -

Resource Consent Applications Issued 7 December – 20 December 2020

Resource Consent applications issued 7 December – 20 December 2020 You can sign up for a web alert at the bottom of Wellington.govt.nz to receive an email when this is updated. A Service Request (SR) number is the individual identification we give each Resource Consent application when lodged with Wellington City Council. If you contact us about any specific consent below, please quote this number. For More information on these consents please phone Customer Services on (04) 801 3590 or email Suburb Address Date SR No. Description Aro Valley 26A Koromiko Road 477196 18/12/2020 Land Use: Additions and alterations Berhampore 466 Adelaide Road 470561 8/12/2020 Change of Conditions: Relating to SR 422685 condition (a) Churton Park 14 Goddard Grove 477052 8/12/2020 Subdivision: Two lot fee simple Churton Park 50 Atherton Terrace 478386 18/12/2020 Land Use: New dwelling and associated earthworks Crofton Downs 82 Silverstream Road 477183 8/12/2020 Land Use: New dwelling and associated earthworks Crofton Downs 28 Porokaiwhiri Street 478280 15/12/2020 Boundary Activity: New dwelling breach Hataitai 5 Rata Road 476357 15/12/2020 Land Use: Upgrading the pathway and new pergola to enhance external character Hataitai 18 Waipapa Terrace 477061 14/12/2020 Land Use: Additions and Alterations Island Bay 59 Witham Street 471575 8/12/2020 Land use and Subdivision: Two lot fee simple and retaining wall. Island Bay 10 Derwent Street 473580 7/12/2020 Land use: Construct deck walkway Island Bay 21 Tyne Street 477742 17/12/2020 Land Use Additions and alterations -

Rapid Transit Network Options Final Draft.Docx Page 1 of 140 Ian Wallis Associates Ltd

Ian Wallis Associates Ltd Let’s Get Wellington Moving – Rapid transit network options Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council Final draft 11 April 2018 (v26) Adam Lawrence [email protected] LGWM rapid transit network options final draft.docx Page 1 of 140 Ian Wallis Associates Ltd Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. Strategic context .............................................................................................................................. 6 2.1.1. RLTP 2015 ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.2. PT Plan 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2. Wellington 2018 bus network .......................................................................................................... 9 3. Network approach and assumptions ....................................................................................... 10 3.1. Rapid transit in Wellington ............................................................................................................ 10 3.2. Patronage drivers ..........................................................................................................................