10645.Ch01.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Song Elite's Obsession with Death, the Underworld, and Salvation

BIBLID 0254-4466(2002)20:1 pp. 399-440 漢學研究第 20 卷第 1 期(民國 91 年 6 月) Visualizing the Afterlife: The Song Elite’s Obsession with Death, the Underworld, and Salvation Hsien-huei Liao* Abstract This study explores the Song elite’s obsession with the afterlife and its impact on their daily lives. Through examining the ways they perceived the relations between the living and the dead, the fate of their own afterlives, and the functional roles of religious specialists, this study demonstrates that the prevailing ideas about death and the afterlife infiltrated the minds of many of the educated, deeply affecting their daily practices. While affected by contem- porary belief in the underworld and the power of the dead, the Song elite also played an important role in the formation and proliferation of those ideas through their piety and practices. Still, implicit divergences of perceptions and practices between the elite and the populace remained abiding features under- neath their universally shared beliefs. To explore the Song elite’s interactions with popular belief in the underworld, several questions are discussed, such as how and why the folk belief in the afterlife were accepted and incorporated into the elite’s own practices, and how their practices corresponded to, dif- fered from, or reinforced folk beliefs. An examination of the social, cultural, * Hsien-huei Liao is a research associate in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at Harvard University, U.S.A. 399 400 漢學研究第20卷第1期 and political impact on their conceptualization of the afterlife within the broad historical context of the Song is key to understand their beliefs and practices concerning the underworld. -

ILMU MAKRIFAT JAWA SANGKAN PARANING DUMADI Eksplorasi Sufistik Konsep Mengenal Diri Dalam Pustaka Islam Kejawen Kunci Swarga Miftahul Djanati

ILMU MAKRIFAT JAWA SANGKAN PARANING DUMADI Eksplorasi Sufistik Konsep Mengenal Diri dalam Pustaka Islam Kejawen Kunci Swarga Miftahul Djanati Nur Kolis, Ph.D. CV. NATA KARYA ILMU MAKRIFAT JAWA SANGKAN PARANING DUMADI Eksplorasi Sufistik Konsep Mengenal Diri dalam Pustaka Islam Kejawen Kunci Swarga Miftahul Djanati Penulis : Hak Cipta © Nur Kolis, Ph.D. ISBN : 978-602-5774-11-9 Layout : Team Nata Karya Desain Sampul: Team Nata Karya Hak Terbit © 2018, Penerbit : CV. Nata Karya Jl. Pramuka 139 Ponorogo Telp. 085232813769 Email : [email protected] Cetakan Pertama, 2018 Perpustakaan Nasional : Katalog Dalam Terbitan (KDT) 260 halaman, 14,5 x 21 cm Dilarang keras mengutip, menjiplak, memfotocopi, atau memperbanyak dalam bentuk apa pun, baik sebagian maupun keseluruhan isi buku ini, serta memperjualbelikannya tanpa izin tertulis dari penerbit . KATA PENGANTAR بسم هللا الرحمن الرحيم Segala puji bagi Allah Tuhan Yang Maha Kuasa, atas segala limpahan nikmat, hidâyah serta taufîq-Nya, sehingga penulis bisa menyelesaikan buku ini. Shalawat dan salam semoga senantiasa dilimpahkan kepada rasul-Nya, yang menjadi uswah hasanah bagi seluruh umat. Buku ini merupakan bagian penting dari pengembangan khazanah Islam di Nusantara yang berhubungan dengan ranah kehidupan mistis masyarakat Jawa, khususnya yang berhubungan dengan pustaka kuno yang dikaji oleh pengamal ajaran mistik Islam kejawen, yaitu ilmu mengenal diri yang dikemas dalam kaweruh sangkan paraning dumadi. Dalam naskah Kunci Swarga Miftahul Djanati terdapat suatu upaya orang Jawa untuk menarik teori tasawuf ke ranah pengamalan praktis dengan menggunakan cara pandang dengan lebih menekankan aspek esoterikal dalam perilaku kehidupan sehari-hari masyarakat Jawa, khususnya dalam memandang hubungan hamba dengan Tuhan dan alam semesta. Tentu saja penekanan aspek kualitas personal manusia sempurna (insan kamil) dikedepankan. -

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

Kota O Muslim ”””

HISNOL MUSLIM “““ KOTA O MUSLIM ””” Inisorat i Shaikh Sa’eed Bin Wahaf Al-Qahttani Iniranon o Manga Ulama Sa Jam’eyat Al-Waqf Al-Islami Marawi City, Philippines Publisher Under-Secretariat for Publications and Research Ministry Of Islamic Affairs, Endownment, Da’wah and Guidance 1426 H. – 2005 ا ا א L א Ğ% אĘ #Ø! אאאĦ ' א% E ) F 4 א3א012/א. - ,א +א! 3א12א0/א א8 úא-1א62 5 ١٤٢٦ = PITOWA So langowan o bantogan na matatangkud a ruk o Allah, ago pangninta a khasokasoyin mantog o Allah sa hadapan o manga malaikat so Nabi tano a so Mohammad ( ) sa irakus Iyanon so manga tonganay niya agoso manga Sohbat iyan sa kasamasama iran. Aya kinitogalinun ami sa basa Mranaw sa maito ini a kitab na arap ami sa oba masabot o manga taw a mata-o sa basa Mranaw na makanggay kiran a gona agoso manga pamiliya iran sa donya Akhirat. Panamaringka a masabotka ini phiyapiya ka an kaomani so sabotka ko Islam. Aya tomiyogalin sa kitaba-i sa basa Mranaw na so manga ulama a manga bara-araparapan ko limo o Allah, a rakus o kiyaimpidiranon: 1-Rashad O. Bacaraman ........... Chairman 2-Ali Dimakayring Alawi ........... Member 3-Abdul Mannan Amirol .......... Member 4-Abu Lais Camal Pocaan ......... Member 5-Sadic Mohammad Usman ..... Member !" 3 Pamkasan Mata-an a so langowan o bantogan na matatangkud a ruk o Allaho, bantogun tano so Allah, ago mangni tano ron sa tabang, ago mangni tano ron sa rila, ago lomindong tano ko Allah phoon ko karata- an o manga ginawa tano, agoso manga rarata ko manga galbuk tano, na sadn sa taw a toro-on -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

An Inquiry Into How Some Muslims and Hindus in Indonesia Relate to Death

An Inquiry into how some Muslims and Hindus in Indonesia Relate to Death EVA ELANA SALTVEDT APPLETON SUPERVISOR Levi Geir Eidhamar Sissel Undheim University of Agder, 2020 Faculty of humanities and pedagogics Department of religion, philosophy and history Doctor, Doctor shall I die? Yes, my child, and so shall I. Rhyme by unknown author 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 5 METHOD ...................................................................................................................... 7 THE EMPIRICAL DATA ..................................................................................................... 7 MOST-SIMILAR SYSTEM DESIGN .................................................................................. 8 LANGUAGE CHALLENGES .............................................................................................. 8 DATA SAMPLING ............................................................................................................... 9 INTERVIEW STRUCTURE ............................................................................................... 10 ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ......................................................................................... 10 GROUNDED THEORY ...................................................................................................... 13 METHODOLOGICAL CHALLENGES ............................................................................. 15 THE RELIGIOUS -

THE CHRONICLE Manufacturer

MORE ACC SOCCER COVERAGE, PAGE 13 THURSDAYTH. NOVEMBER 5. 1987-i! E CHRONICLE DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL. 83, NO. 48 State match to Study indicates open first ACC sweetener not a soccer tourney headache cause By JOHN SENFT fWLJf By CHRIS SCHMALZER As the inaugural Atlantic Coast Con A study conducted at Duke Univer ference Soccer Tournament opens today, sity Medical Center and funded by the it promises to be more than a simple National Institute of Health and the showcase of some of the premier talent in manufacturer of Nutrasweet has con the country. Instead, for most of the cluded that the artificial sweetener is teams, it may turn into a war for survival. not likely to cause headaches in the The winner of the tournament receives general population. an automatic bid for the postseason The findings of the study, which NCAA Tournament. Traditionally, the began in October 1986 and involved 40 NCAA awards between two to five bids for volunteer subjects, were announced at every region, and in the strong South a press conference at the Medical region the competition for bids is fierce. Center Wednesday. The results will Third-ranked South Carolina appears to appear in today's issue of the New be a virtual certainty for one, and Duke England Journal of Medicine. has an inside track on a second. But "This study answers the question of North Carolina, Clemson, N.C. State and headaches" in relation to aspartame, Wake Forest are all sitting on the fence the generic name for Nutrasweet, said —a first-round loss will probably' mean Susan Schiffman, a professor of medi the end of their season. -

Download Eternal Yoga: Awakening Within Buddhic Consciousness

ETERNAL YOGA: AWAKENING WITHIN BUDDHIC CONSCIOUSNESS DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Virochana Khalsa | 216 pages | 01 Jan 2003 | Books of Light Publishing, US | 9781929952052 | English | Crestone, CO, United States Subtle body According to Theosophists, after the physical plane is the etheric plane and both of these planes are connected to make up the first plane. There is a bit more to it, but this shows possibilities. Other offers may also be available. Tian Diyu Youdu. These are understood to determine the characteristics of the physical body. Human personality and its survival of death. Eternal Yoga is a way of discovering our eternal nature. The journey is still far from over, if one is always fresh and willing. Most cosmologists today believe that the universe expanded from a singularity approximately The ancient Eternal Yoga: Awakening within Buddhic Consciousness mythology gave the name " Ginnungagap " to the primordial "Chaos", which was bounded upon the northern side by the cold and foggy " Niflheim "—the land of mist and fog—and upon the south side by the fire " Muspelheim ". A millennium later, these concepts were adapted and refined by various spiritual traditions. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. You have to let go of it and just sense and know there is something that keeps going up, deeper, straight, and without support. Along with him there are various planes intertwined with the quotidian human world and are all inhabited by multitudes of entities. Show More Show Less. Psycho-spiritual constituents of living beings, according to various esoteric, occult, and mystical teachings. At first in this kind of activation, typically a combination of Eternal Yoga: Awakening within Buddhic Consciousness seed thoughts and karmas increase, and combine with a projection of a busy egoic mind and emotions into that space. -

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Ruizhong Ding aus Qishan, VR. China Bonn, 2019 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Dr. Manfred Hutter, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Kubin, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Betreuer und Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Ralph Kauz, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Veronika Veit, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (weiteres prüfungsberechtigtes Mitglied) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung:22.07.2019 Acknowledgements Currently, when this dissertation is finished, I look out of the window with joyfulness and I would like to express many words to all of you who helped me. Prof. Wolfgang Kubin accepted me as his Ph.D student and in these years he warmly helped me a lot, not only with my research but also with my life. In every meeting, I am impressed by his personality and erudition deeply. I remember one time in his seminar he pointed out my minor errors in the speech paper frankly and patiently. I am indulged in his beautiful German and brilliant poetry. His translations are full of insightful wisdom. Every time when I meet him, I hope it is a long time. I am so grateful that Prof. Ralph Kauz in the past years gave me unlimited help. In his seminars, his academic methods and sights opened my horizons. Usually, he supported and encouraged me to study more fields of research. -

Spring.2012 the Muse the Literary & Arts Magazine of Howard Community College

The Muse spring.2012 The Muse The Literary & Arts Magazine of Howard Community College Editorial Committee Mark Grimes Tara Hart Lee Hartman Stacy Korbelak Sylvia Lee William Lowe Juliette Ludeker Ryna May Patricia VanAmburg Student submissions reviewed and selected by editorial committee. Faculty and staff submissions reviewed and selected by non-contributing editors. Design Editor Stephanie Lemghari Cover Art “The Weight of Mercy” by Lindsay Anne Dransfield Our Tenth Anniversary Issue Ten is an important number. Decades are defining. We promised years ago, Duncan Hall has become an think of ourselves as in our twenties, thirties, forties, or open book itself, its hallways and classrooms lined beyond, sliding over the dozens and other numbers in with some of the best student poetry published here, between. inviting our responses and conversations. The Muse is no longer in its infancy, but a vibrant, Even in this digital age, or perhaps more so, we articulate literary and artistic celebration of spring that treasure beautiful things we can hold in our hands, annually invites submissions from students, faculty, staff, dip into, come across, hand to someone and say, “Look alumni, and the community; brings the editors and at this.” Seeing a copy of the Muse somewhere on designers together to read, discuss, marvel, compare, campus, at home, or in the community always brings distinguish, and choose; and culminates in an increasingly a jolt of pleasure, especially as the art on the covers is festive reading of the works published (beautifully, may I chosen with such care, so that even a glimpse is a gift. -

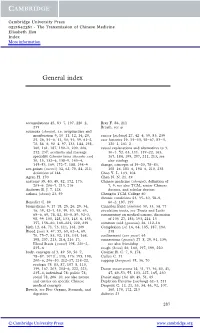

General Index 287

Cambridge University Press 0521642361 - The Transmission of Chinese Medicine Elisabeth Hsu Index More information General index 287 General index accumulations 45, 83–7, 197, 220–2, Bray F. 86, 211 235 Breath, see qi acumoxa (zhenjiu), i.e. acupuncture and moxibustion 9, 10–11, 12, 14, 20, cancer (aizheng) 27, 42–4, 59, 83, 239 25, 26, 34–6, 41, 50, 54, 59, 61–2, case histories 19, 34–44, 58–67, 83–4, 70, 84–6, 90–4, 97, 133, 144, 158, 120–1, 161–2 160, 161, 187, 190–1, 200, 206, causal explanations and alternatives to 3, 212, 237; acumoxa and massage 30–1, 52, 63, 111, 119–22, 163, speciality (zhenjiu tuina zhuanke xue) 167, 184, 199, 207, 211, 213; see 10, 15, 132–6, 138–9, 143–4, also etiology 145–53, 169, 172–7, 188, 198–9 change, concepts of 19–20, 78–83, acu-points (xuewei) 34, 62, 70, 84, 211; 108–16, 181–6, 194–6, 210, 238 definition of 144 Chao Y. L. 103, 104 Agren H. 170 Chen N. N. 21, 49 anatomy 39, 40, 49, 82, 172, 173, Chinese medicine (zhongyi), definition of 205–6, 206–7, 213, 216 7, 9; see also TCM, senior Chinese Andrews B. J. 7, 128 doctors, and scholar doctors asthma (chuan) 23, 59 Chengdu TCM College 60 chronic conditions 23, 35– 40, 58–9, Benedict C. 89 60–2, 197, 199 biomedicine 9, 17–18, 25, 26, 29, 34, Cinnabar Field (dantian) 30, 33, 34, 77 36, 39, 42–3, 45, 49, 50, 58, 63, circulation tracts, see Tracts and Links 65–6, 69, 78, 82, 83–5, 89, 92–3, commentary on medical canons, discussion 98, 99–100, 128, 133, 145–6, 155, of 105–27, 186, 193, 214–15 157, 158–60, 168–224, 229, 239 common cold (ganmao) 26, 112–16 birth 12, 64, 71, 73, 111, 161, 209 Complexion (se) 16, 64, 185, 187, 190, Blood (xue) 3, 47, 55, 60, 62–4, 69, 218 70, 75–7, 83, 92, 118, 144, 168, confinement (zuo yuezi) 64 198, 207, 213, 214, 216–17; connections (guanxi) 27–8, 29, 91, 139; Blood Stasis ( yuxue) 198, 220–2, see also friendship 235–6 cough (kesou) 26, 160, 197, 199, 220 body, concepts of 3, 49–50, 56–7, Croizier R. -

To Hell, with Shakespeare

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 7(C) (2010) 317–325 International Conference on Learner Diversity 2010 To Hell, with Shakespeare Lee Eileena,* aSchool of Creative Arts & Communication, Sunway University College, Bandar Sunway, 46150 Petaling Jaya, Malaysia Abstract In the teaching of Shakespearean plays to ESL students, deciphering Shakespeare’s language has often been cited as the main obstacle to comprehending his work. This paper reports on how the researcher tapped on the diverse religious beliefs of the students and used Taoist, Muslim, and Hindu concepts of the afterlife as a prelude to teach and read the Porter’s scene. As a result of the creative methodology used in the class, the ESL students were able to discuss and comprehend Shakespeare’s treatment of Hell and grasp the concept of black comedy in the play. © 2010 Published by Elsevier Ltd. Open access under CC BY-NC-ND license. Keywords: Hell, humor, comic relief, background knowledge/schema, the aesthetic experience 1.Introduction Shakespeare’s language has often been cited as the main obstacle to comprehending his work; whilst this may hold true to a large extent, in the teaching of Shakespeare in the English as a Second Language (ESL) classroom, there are other ‘aspects’/’areas’ in Shakespeare’s plays that are equally demanding for the ESL reader such as the concept of Hell and black humor. Humor is not only relative but it is also time and culture-bound; in the case of the Malaysian classroom, getting students from different ethnic and religious backgrounds to comprehend the black humor in the Porter’s scene in Macbeth is no laughing matter.