Reframing Public Housing in Richmond, Virginia: Segregation, Resident Resistance and the Future of Redevelopment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Church Hill North, Richmond, VA

Exploring the Health Implications of Mixed-Income Communities January 2019 Mixed-Income Strategic Alliance Church Hill North Richmond, VA Executive Summary approaches to the complex problems of housing quality and stability, concentrated poverty, asset development, This site profi le is part of a series that spotlights food deserts, etc. This profi le also notes the challenges mixed-income community transformations that empha- that arise when the prioritizing and balancing of physical size health and wellness in their strategic interventions. development and human capital development are not The Mixed-Income Strategic Alliance produced these fully in sync. profi les to better understand the health implications of creating thriving and inclusive communities with a socio- The takeaways from this process are, fi rst, the caution to economically and racially diverse population. This site local leaders about the limitations of what can be accom- profi le, which focuses on Creighton Court (and the new plished without federal resources and leadership and the mixed-income community Church Hill North) was de- necessary precondition of consistent local leadership veloped through interviews with local stakeholders and at the City and Housing Authority. Public capacity can’t experts as well as a review of research, publicly-available be replaced with or relegated to civic leaders, despite information, and internal documents. best intentions. In addition, while there are ample efforts targeted to addressing the social determinants of health Creighton Court is a public housing development in in the East End, the importance of balancing physical the East End neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia. To development with the other aspects of mixed-income address the issues surrounding this pocket of racially communities is particularly evident. -

管 内 発 生 の 重 要 犯 罪 1/1~1/31 アラバマ 中部地区(Area Code 205)

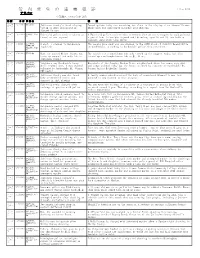

管 内 発 生 の 重 要 犯 罪 1/1~1/31 アラバマ 中部地区(Area Code 205) 場 所 日 付 事 案 名 概 要 ジェフ 1/7/2013 殺人事件 Jefferson County's first slaying Investigators today are searching for clues in the slaying of an Adamsville man ァーソ ン victim of 2013 identified as whose body was discovered Saturday near Maytown. Adamsville man ジェフ 1/9/2013 銃器使用の事 Fairfield police officer shoots at A Fairfield police officer this afternoon shot at two teenagers he said pointed ァーソ 件 ン teens; no one injured a gun at him. No one was injured and the males, ages 18 and 19, are both in custody, said Chief Leon Davis. ジェフ 1/10/2013 殺人事件, 2 shot, 1 stabbed in Gardendale Two people were shot and one stabbed in the 5800 block of Country Meadow Drive ァーソ 傷害事件, ン 銃器使用の事 (updated) in Gardendale, according to Gardendale police this afternoon. 件 ジェフ 1/10/2013 薬物事案 Hunt for wanted Blount County man The search for a wanted man not only turned up the suspect today, but also ァーソ ン turns up suspect and meth lab in turned up a methamphetamine lab in Mt. Olive. Jefferson County ジェフ 1/10/2013 殺人事件, Neighbors say Gardendale house Residents of the Country Meadow Drive neighborhood where two women were shot ァーソ 傷害事件, ン 銃器使用の事 where 2 women shot, 1 man stabbed and a man stabbed today say the house is owned by a pastor of Gardendale-Mt. 件 belonged to Gardendale-Mt. Vernon Vernon United Methodist Church. -

Expansion and Exclusion: a Case Study of Gentrification in Church Hill Kathryn S

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2016 Expansion and Exclusion: A Case Study of Gentrification in Church Hill Kathryn S. Parkhurst Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Oral History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons © The Author Downloaded from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Expansion and Exclusion: A Case Study of Gentrification in Church Hill A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. By Kathryn Schumann Parkhurst Bachelor of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Master of Teaching, University of Virginia, 2010 Director: Dr. John T. Kneebone Associate Professor and Chair, Virginia Commonwealth University Department of History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2016 Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................................3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................4 Chapter 1: Renewal -

2019-2020 Annual Report

C ITY OF R ICHMOND D EPARTMENT OF P LANNING AND D EVELOPMENT R EVIEW 2019-2020 Annual Report to Virginia State Historic Preservation Office City of Richmond Section 106 Review of Undertakings for the period July 1, 2019 through June 30, 2020 Please accept the following materials in fulfillment of the Programmatic Agreement requirement that the City of Richmond shall annually compile a report of all undertakings reviewed by the City for the twelve- month period ending June 30. Annual Report Components: • Report Narrative • Undertakings the City completed in consultation with the SHPO • Undertakings the City completed without consultation with the SHPO in accordance with Stipulations IV (C) 1, IV (D) 2, and V (B) of the Agreement • Resume of staff that implements the agreement • Statement of Professional Qualifications Supplemental Materials • Summary Reports (2) by finding and activity • Maps depicting Section 106 Activity for the past year Report Narrative In this report and accompanying materials, the City is seeking to fulfill the annual reporting requirements under the Programmatic Agreement. The two required categorical reports (based on consultation/non-consultation with the SHPO) were generated from the City-maintained Section 106 database and include, for each project, the address of the affected property, the type of undertaking, the finding of effect, the action dates of the Section 106 process, and all comments and conditions pertaining to the conclusion of the review. The City is confident in the accuracy of the content of the reports. The City has included two additional reports that summarize the undertaking types and the finding determinations made over the past year. -

Creighton Phase a 3100 Nine Mile Road Richmond, Virginia 23223

Market Feasibility Analysis Creighton Phase A 3100 Nine Mile Road Richmond, Virginia 23223 Prepared For Ms. Jennifer Schneider The Community Builders, Incorporated 1602 L Street, Suite 401 Washington, D.C., 20036 Authorized User Virginia Housing 601 South Belvidere Street Richmond, Virginia 23220 Effective Date February 4, 2021 Job Reference Number 21-126 JP www.bowennational.com 155 E. Columbus Street, Suite 220 | Pickerington, Ohio 43147 | (614) 833-9300 Market Study Certification NCHMA Certification This certifies that Sidney McCrary, an employee of Bowen National Research, personally made an inspection of the area including competing properties and the proposed site in Richmond, Virginia. Further, the information contained in this report is true and accurate as of February 4, 2021. Bowen National Research is a disinterested third party without any current or future financial interest in the project under consideration. We have received a fee for the preparation of the market study. However, no contingency fees exist between our firm and the client. Virginia Housing Certification I affirm the following: 1. I have made a physical inspection of the site and market area 2. The appropriate information has been used in the comprehensive evaluation of the need and demand for the proposed rental units. 3. To the best of my knowledge the market can support the demand shown in this study. I understand that any misrepresentation in this statement may result in the denial of participation in the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program in Virginia as administered by Virginia Housing. 4. Neither I nor anyone at my firm has any interest in the proposed development or a relationship with the ownership entity. -

Expansion and Exclusion: a Case Study of Gentrification in Church Hill

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2016 Expansion and Exclusion: A Case Study of Gentrification in Church Hill Kathryn S. Parkhurst Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Oral History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4098 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Expansion and Exclusion: A Case Study of Gentrification in Church Hill A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. By Kathryn Schumann Parkhurst Bachelor of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Master of Teaching, University of Virginia, 2010 Director: Dr. John T. Kneebone Associate Professor and Chair, Virginia Commonwealth University Department of History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2016 Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................................3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................4 -

City of Richmond, Virginia

City of Richmond, Virginia Program Year 2020 CONSOLIDATED ANNUAL ACTION PLAN Department of Housing and Community Development June 8, 2020 DUNS No. 003133840 Annual Action Plan 1 2020 OMB Control No: 2506-0117 (exp. 06/30/2018) TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ...........................................................................3 Lead & Responsible Agencies ............................................................ 9 AP-10 Consultation ......................................................................... 10 AP-12 Participation ......................................................................... 15 AP-15 Expected Resources .............................................................. 20 AP-20 Annual Goals and Objectives ................................................. 30 AP-35 Project .................................................................................. 37 AP-38 Projects Summary ................................................................. 39 AP-50 Geographic Distribution ........................................................ 74 AP-55 Affordable Housing ............................................................... 76 AP-60 Public Housing ...................................................................... 77 AP-65 Homeless and Other Special Needs Activities ........................ 79 AP-70 HOPWA Goals ....................................................................... 81 AP-75 Barriers to Affordable Housing .............................................. 82 AP-85 Other Actions ....................................................................... -

Your New Grtc March 2017 Public Comments/Questions

YOUR NEW GRTC MARCH 2017 PUBLIC COMMENTS/QUESTIONS DATE QUESTION/COMMENT/FEEDBACK ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS I once again I find myself in the same position of losing bus transportation to and from work each day. Pursuant to our previous conversations, I changed my route from the 66x Spring Rock Green Express to the 64x Stony Point Express. This change did result in additional gasoline and miles traveled as well as a change in my work schedule. Now it is my understanding that the 64x schedule may be changed resulting in a decrease in the number of trips per day. As before I have completed the survey and been made aware of the public meetings. I am not sure that I have any available options to get me to work by 7 am and from work at 3:30 pm once this route is changed or eliminated. 3/3/17 EMAIL I appreciate your comments in this matter. 3/7/17 EMAIL Have the 7-Pines bus on the way to Downtown Richmond service the Airport. 3/8/17 Meeting Every 15 minutes throughout the service hours. 10 Southside Plaza What is the BRT frequency? minutes AM/PM peak 3/8/17 Meeting Southside Plaza Is there going to be a Route 6 reduction? I don't see it on this map. There is no more Route 6. This plan eliminates it. That is correct, the Route 6 was originally planned to be reduced, but stay in place to provide local fixed route service alongside the Pulse. However, with this City 3/8/17 Meeting redesign process, the City took that service to other Southside Plaza But that wasn't in the original plan for the BRT, right? high frequency and coverage routes in the City. -

Public Housing Agency

R I C H M O N D R E D E V E L O P M E N T & H O U S I N G A U T H O R I T Y Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority (RRHA) Annual Agency Plan Fiscal Year 2021 - 2022 Annual PHA Plan 4 PHA Information 4 Annual Plan Elements 5 Statement of Capital Improvements 6 B.1 – Revision of PHA Plan Elements 7 Housing Needs of Families on the Public Housing (Elderly) Waiting Lists as of July 24, 2020 9 Housing Needs of Families on the Housing Choice Voucher (HCVP) Waiting List as of July 24, 2020 11 Strategy for Addressing Housing Needs (Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice) 17 Reasons for Selecting Strategies 19 B1: Revision of PHA Plan Elements: ACOP 20 Financial Resources: 22 Planned Sources and Uses 23 B.2 – New Activities 29 Designated Housing for Elderly and/or Disabled Families 38 Conversion of Public Housing to Tenant-Based Assistance 38 Conversion of Public Housing to Project-Based Assistance under RAD 39 Non- Smoking Policies 73 Project-Based Vouchers 74 Other Capital Grant Programs 74 B.3 Civil Rights Certification 75 B.5 – Progress Report 75 B.6 Resident Advisory Board (RAB) Comments 85 B.7 Certification by State and Local Officials 86 C.1 Capital Improvements 86 2 Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority (RRHA) Annual Agency Plan Fiscal Year 2021 - 2022 3 Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority (RRHA) Annual Agency Plan Fiscal Year 2021 - 2022 Annual PHA Plan U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development OMB No. -

Social Enterprise Feasibility Analysis

Richmond, Virginia: Social Enterprise Feasibility Analysis Reducing Poverty and Building Community Wealth through Social Enterprise Steve Dubb and Alex Rudzinski with research support from Carol Reese and Emily Sladek Final Report Submitted to the City of Richmond June 2016 (Contract #16000004755) richmond, virginia: social enterprise feasibility analysis Richmond, Virginia: Social Enterprise Feasibility Analysis Reducing Poverty and Building Community Wealth through Social Enterprise Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Overview, Background, and Democracy Collaborative Methodology 8 Project Background 8 Why Social Enterprise? 8 Understanding the Context: Poverty and Assets in the East End 13 Methodology 17 Interview and Research Findings 17 Project Champion 19 Anchor Institution Support 19 Viable Business Opportunities 21 Business Idea 1: Richmond Community Construction 21 Business Idea 2: Richmond Community and Property Maintenance Cooperative 23 Business Idea 3: Richmond Community Health (and related enterprises) 24 Additional Business Opportunities 29 Business Development Resources and Industry Expertise 32 Available Financing 33 Political and Community Support 33 Workforce Development 34 Wrap-Around Services 34 Community Loan Fund Incubator 35 Complementary Strategies and Programs 35 Success Factor Summary 35 Designing a Nonprofit Business Development Organization to Achieve Impact 36 Structure and Governance 36 Roles, Responsibilities, and Key Organizational Features 37 Getting Started 40 Concluding Recommendations 41 Appendix -

Growing up in Civil Rights Richmond: a Community Remembers

Growing Up in Civil Rights Richmond A COMMUNITY REMEMBERS Photographs by I BRIAN PALMER Growing Up in Civil Rights Richmond A COMMUNITY REMEMBERS II 1 Growing Up in Civil Rights Richmond A COMMUNITY REMEMBERS Zenoria Abdus-Salaam Rev. Josine C. Osborne Philip H. Brunson III Valerie R. Perkins Paige Lanier Chargois Mark Person John Dorman Royal Robinson Leonard L. Edloe Elizabeth Salim Glennys E. Fleming Myra Goodman Smith Reginald E. Gordon Deborah Taylor Robert J. Grey, Jr. Yolanda Burrell Taylor Woody Holton Mary White Thompson Virginia P. Jackson Loretta Tillman Mark R. Merhige Daisy E. Weaver Renee Fleming Mills Michael Paul Williams Yvonne A. Mimms-Evans Nell Draper Winston Rev. Robin D. Mines Rebecca S. Wooden Tab Mines Carol Y. Wray PHOTOGRAPHS Brian Palmer ESSAYS Elvatrice Belsches Laura Browder Ashley Kistler Michael Paul Williams UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND MUSEUMS Brian Palmer, Untitled [20 February 2018, Virginia Civil Rights Memorial, Virginia State Capitol, Richmond], archival inkjet print on paper, 33.3 x 50 inches, lent courtesy of the artist 2 Published on the occasion of the exhibition TABLE OF CONTENTS Growing Up in Civil Rights Richmond: A Community Remembers Joel and Lila Harnett Museum of Art University of Richmond Museums January 17 to May 10, 2019 Organized by the University of Richmond Museums, the exhibition was developed by Ashley Kistler, independent curator, and Laura Browder, Tyler and Director’s Foreword Alice Haynes Professor of American Studies, University of Richmond. Richard Waller ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 The exhibition, related programs, and publication are made possible in part with funds from the Louis S. Booth Arts Fund and with support from the University’s Cultural Affairs Committee. -

Overview of Existing Conditions

Overview 3 of Existing Conditions Summary East End Cemetery contains layers of information that generate additional questions after each day of investigation. This chapter provides a survey of the existing conditions and an analysis of opportunities and challenges. 30 EAST END CEMETERY MASTER PLAN 3.1 Oakwood-Chimborazo National Historic District East End Cemetery is located on the far eastern The District has an eclectic collection of 1,606 corner of the City of Richmond, separated from buildings, of which the majority is a diverse the rest of the city by Gillies Creek and Stony Run. collection of Late Victorian, Greek Revival, and Its eastern boundary is marked by the Henrico Italianate structures. The cemetery provides County line. The Oakwood-Chimborazo National visible evidence of the growth and evolution Historic District extends from Oakwood Cemetery of the community as a potential contributing and Historic Evergreen Cemetery as its north resource to the district. Therefore, if the cemetery terminus to Gillies Creek Park and East Broad is incorporated into the District, East End may be Street as its south terminus. East End Cemetery, eligible for federal or state tax credits. while not currently included in the District, fi ts within the District's primary period HENRICO COUNTY of signifi cance, dating from CITY OF RICHMOND 1820 to 1950. CREIGHTON RD Legend East End Cemetery DABBS HENRICO HOUSE COUNTY Privately-owned MUNICIPAL W NINE MILE RD (33) Cemetery COMPLEX FAIRMOUNT City-owned Cemetery City/County-owned COLORED PAUPERS Park