Tiberius and the Taste of Power: the Year 33 in Tacitus*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phaedrus Plato

Phaedrus Plato TRANSLATED BY BENJAMIN JOWETT ROMAN ROADS MEDIA Classical education, from a Christian perspective, created for the homeschool. Roman Roads combines its technical expertise with the experience of established authorities in the field of classical education to create quality video courses and resources tailored to the homeschooler. Just as the first century roads of the Roman Empire were the physical means by which the early church spread the gospel far and wide, so Roman Roads Media uses today’s technology to bring timeless truth, goodness, and beauty into your home. By combining excellent instruction augmented with visual aids and examples, we help inspire in your children a lifelong love of learning. Phaedrus by Plato translated by Benjamin Jowett This text was designed to accompany Roman Roads Media's 4-year video course Old Western Culture: A Christian Approach to the Great Books. For more information visit: www.romanroadsmedia.com. Other video courses by Roman Roads Media include: Grammar of Poetry featuring Matt Whitling Introductory Logic taught by Jim Nance Intermediate Logic taught by Jim Nance French Cuisine taught by Francis Foucachon Copyright © 2013 by Roman Roads Media, LLC Roman Roads Media 739 S Hayes St, Moscow, Idaho 83843 A ROMAN ROADS ETEXT Phaedrus Plato TRANSLATED BY BENJAMIN JOWETT INTRODUCTION The Phaedrus is closely connected with the Symposium, and may be regarded either as introducing or following it. The two Dialogues together contain the whole philosophy of Plato on the nature of love, which in the Republic and in the later writings of Plato is only introduced playfully or as a figure of speech. -

Charles Alexander Robinson, Jr. Memorial Lecture

DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS 48 College Street, Box 1856 Macfarlane House Providence, RI 02912 Phone: 401.863.1267 Fax: 401.863.7484 CHARLES ALEXANDER ROBINSON, JR. MEMORIAL LECTURE 1. October 14, 1965 “Vitruvius and the Greek House” • Richard Stillwell, Princeton University 2. November 15, 1966 “Second Thoughts in Greek Tragedy” • Bernard M. W. Knox 3. March 23, 1967 “Fiction and Fraud in the Late Roman Empire” • Sir Ronald Syme 4. November 29, 1967 “The Espionage-Commando Operation in Homer” • Sterling Dow, Harvard University 5. November 21, 1968 “Uses of the Past” • Gerald F. Else, University of Michigan 6. November 5, 1969 “Marcus Aurelius and Athens” • James H. Oliver, Johns Hopkins University 7. March 1, 1971 “Between Literacy and Illiteracy: An Aspect of Greek Culture in Egypt” • Herbert C. Youtie, University of Michigan 8. October 27, 1971 “Psychoanalysis and the Classics” • J. P. Sullivan, SUNY Buffalo 9. November 14, 1972 “The Principles of Aeschylean Drama” • C. J. Herington, Yale University 10. October 30, 1973 “Alexander and the Historians” • Peter Green, University of Texas, Austin 11. November 6, 1974 “The Emotional Power of Greek Tragedy” • W. Bedell Stanford, Trinity College, Dublin 12. March 10, 1976 “Personality in Classical Greek Sculpture” • George M.A. Hanfmann, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University 13. March 28, 1977 “The Odyssey” • John M. Finley, Harvard University 14. November 21, 1978 “Community of Men and Gods in Ancient Athens” • Homer A. Thompson, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton 15. April 23, 1979 “Oedipus’ Mother” • Anne Pippin Burnett, University of Chicago 16. March 17, 1980 “Rustic Urbanity: Roman Satirists in and outside Rome” • William S. -

The Last Generation of the Roman Republic Free Download

THE LAST GENERATION OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC FREE DOWNLOAD Erich S. Gruen | 615 pages | 01 Mar 1995 | University of California Press | 9780520201538 | English | Berkerley, United States Erich S. Gruen Gruen's argument is that the Republic was not in decay, and so not necessarily in need of "rescue" by Caesar Augustus and the institutions of the Empire. Audible 0 editions. I hate that. This massive, articulate work has stood the test of time, and, if not indispensable it is still highly regarded and a standard guide to the period. The method is hazardous and delusive. Appius Claudius Pulcher consul 54 BC. This article needs additional citations for verification. We know what it's like to be in the weeds with a chunk of the written word. You can help The Last Generation of the Roman Republic by expanding it. Namespaces Article Talk. Open Preview See a Problem? Namespaces Article Talk. Published February 28th by University of California Press first published Philistine comment aside, he had a point - this book was work. I often found the real chestnuts of information were often contained in The Last Generation of the Roman Republic footnotes. He systematically challenges every theory in order to reveal their weaknesses and to validate his own thesis. Get it now! Wiseman Erich S. It's an important work, up there with Syme, the review spurred me to want to buy it--again, I had a copy once and it's disappeared after several moves. In this case The Last Generation of the Roman Republic others, recent historical research has supported some of the theories that Gruen challenged. -

Plato's Phaedrus and Apuleius' Metamorphoses1

“Necessary Roughness”: Plato’s Phaedrus and Apuleius’ Metamorphoses1 JEFFREY T. WINKLE Calvin College Introduction Readers of Apuleius have long recognized the influence of Plato’s Phaedrus (along with other Platonic works) on his Metamorphoses, especially in the allegorical elements of the “Cupid and Psyche” centerpiece.2 Outside of “Cu- pid and Psyche” a handful of other allusions to the Phaedrus in the novel have been widely noted3 but it is the contention of this essay that elements of Plato’s Phaedrus are more deeply embedded in the themes and overall narrative(s) of the Apuleian novel than previously recognized. Reading the whole of the novel closely against the Phaedrus reveals that just as this particular dialogue provides a useful interpretive touchstone for the “Cupid and Psyche” tale, it functions in a similar and deliberate way for the novel’s principal narrative concerning Lucius, acting as backdrop to and underlining what we might call his fall and redemption. What follows is not an argument that the Phaedrus ————— 1 I am very grateful to my colleagues Ken Bratt, U.S. Dhuga, and David Noe for their helpful comments on an early draft of the essay as well as to Luca Graverini and the journal refer- ees especially for bringing me up to speed on recent scholarship and talking me down from particular interpretive ledges. 2 For Phaedrean (and other Platonic) influence on Cupid and Psyche see: Hooker 1955; Walsh 1970, 55ff, 195, 206ff; Penwill 1975; Anderson 1982, 75-85; Kenney 1990, 17-22; Schlam 1992, 82-98; Shumate 1996, 259ff; Dowden 1998; O’Brien 1998; Zimmerman 2004; Graverini 2012a, 112-113. -

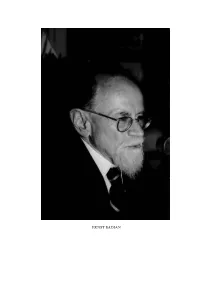

In This, One of the Last Photographs Taken of Sir Ronald Syme OM, He Is

In this, one of the last photographs taken of Sir Ronald Syme OM, he is shown with Sir Isaiah Berlin OM and Lord Franks OM on 16 June 1989 before the Foundation Dinner at Wolfson College, Oxford, of which he was an Extraordinary Fellow from his retirement from the Camden Chair in 1970 until his death on 4 September 1989. Copyright, Times Newspapers SIR RONALD SYME i903-i989 ... non Mud culpa senectae sed labor intendens animique in membra vigentis imperium vigilesque suo pro Caesare curae dulce o/>«s*(Statius, Silvae 1.4, cf. RP v, 514) The death of Sir Ronald Syme on 4 September 1989 has deprived the Roman Society of its most distinguished member and the world of classical scholarship of its foremost historian. Elected to life membership of the Society in 1929 when he became a Fellow of Trinity College, Oxford, Syme joined the Editorial Committee in 1931, became a Vice- President in 1938, and served an extended term as President from 1948 to 1952. This was a crucial period during which the arrangements were made for housing the Hellenic and Roman Societies and their Joint Library in the new Institute of Classical Studies in Gordon Square. Thereafter Syme remained an active member of the Society, whose secretaries, as Patricia Gilbert attests, valued him as a wise and accessible counsellor. He also lectured for the Society and advised Editors of this Journal, in which many articles of his continued to appear. Ronald Syme died three days before the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of the Roman Revolution, at the age of eighty-six. -

Intersection of Poetic and Imperial Authority in Phaedrus’ Fables

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The Intersection of Poetic and Imperial Authority in Phaedrus’ Fables Version 1.0 February 2008 Brigitte B. Libby Princeton University Abstract: Phaedrus wrote two fables featuring Roman emperors. In Fable 2.5 we find Emperor Tiberius giving a busybody his deserved come-uppance, and in Fable 3.10 Augustus miraculously solves a murder-suicide case. Yet couched among so many of Phaedrus’ fables that criticize authority figures, these positive portrayals of the emperors come as a surprise to the reader and present a significant problem of interpretation. In exploring the different possible readings of the two poems, this paper follows Phaedrus through a complex interpretive maze and shows how the fabulist’s own self-portrayal intersects with and colors his portrayal of the first two Roman emperors. © Brigitte B. Libby. [email protected] 1 The Intersection of Poetic and Imperial Authority in Phaedrus’ Fables1 Introduction Despite Phaedrus' status as the first versifier of the Aesopic corpus, and the first to structure these fables in a single poetic book, he has sparked little scholarly interest in the field of Roman poetry until the past decade. With the recent studies by J. Henderson and E. Champlin, however, Phaedrus has garnered both attention and praise not merely for his role in the Aesopic tradition, but also for his own achievement as an innovative fabulist. 2 Most of Phaedrus’ fables are traditional Aesopic stories starring a variety of animals and plants, but several fables are considered original to Phaedrus, as they deal with more historical or typically Roman themes such as public figures or law courts. -

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011 THE ANCIENT HISTORIAN ERNST BADIAN was born in Vienna on 8 August 1925 to Josef Badian, a bank employee, and Salka née Horinger, and he died after a fall at his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, on 1 February 2011. He was an only child. The family was Jewish but not Zionist, and not strongly religious. Ernst became more observant in his later years, and received a Jewish funeral. He witnessed his father being maltreated by Nazis on the occasion of the Reichskristallnacht in November 1938; Josef was imprisoned for a time at Dachau. Later, so it appears, two of Ernst’s grandparents perished in the Holocaust, a fact that almost no professional colleague, I believe, ever heard of from Badian himself. Thanks in part, however, to the help of the young Karl Popper, who had moved to New Zealand from Vienna in 1937, Josef Badian and his family had by then migrated to New Zealand too, leaving through Genoa in April 1939.1 This was the first of Ernst’s two great strokes of good fortune. His Viennese schooling evidently served Badian very well. In spite of knowing little English at first, he so much excelled at Christchurch Boys’ High School that he earned a scholarship to Canterbury University College at the age of fifteen. There he took a BA in Classics (1944) and MAs in French and Latin (1945, 1946). After a year’s teaching at Victoria University in Wellington he moved to Oxford (University College), where 1 K. R. Popper, Unended Quest: an Intellectual Autobiography (La Salle, IL, 1976), p. -

Phaedrus the Fabulous Author(S): Edward Champlin Source: the Journal of Roman Studies, Vol

Phaedrus the Fabulous Author(s): Edward Champlin Source: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 95 (2005), pp. 97-123 Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20066819 Accessed: 23/03/2010 20:03 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sprs. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Roman Studies. http://www.jstor.org Phaedrus The Fabulous EDWARD CHAMPLIN I In the Prologue to the third book of his fables, Phaedrus complains bitterly to a patron. -

Living with the Gods in Fables of the Early Roman Empire

10.1628/219944615X14448150487355 Teresa Morgan Living with the Gods in Fables of the Early Roman Empire Abstract This essay builds on work by the author on ancient cognitive religiosity and the Aesopic corpus. Focusing on fables datable to the early principate, it argues that, despite their debt to Aesop, their representations of divine-human relations are in some ways distinctive. Three fables are read closely to show the complexities of reli- gious thinking, particularly about relations between individuals and gods, that may be embedded in apparently naive stories. Keywords: Aesop, Babrius, Phaedrus, Plutarch, fables, gods, cognitive religiosity, oli- gotheon, monotheism 1 Introduction Delivered by Ingenta Copyright Mohr Siebeck In a recent article, I explored evidence for popular thinking about divine- human relations in Aesopic fables, arguing that fables are an under-used resource for the study of Greco-Roman cognitive religiosity.1 This essay ? 141.211.4.224 Wed, 18 Jul 2018 13:25:51 pursues a similar theme in a related corpus: fables told or retold under the early principate. Fables hold a distinctive place in Greco-Roman culture.2 From the archaic period, if not earlier, to the end of antiquity and beyond, they were con- stantly retold and reinterpreted. Collected under the name of Aesop from at least the fourth century BCE,3 in the early principate they developed a new form, the single-authored biblion or libellus.4 They were used by philoso- 1 Morgan 2013; cf. Morgan 2007, 5–8, Kurke 2011, 2–16, chh. 2–4. 2 On the definition of fable see Morgan 2007, 57–60; the fables discussed in this paper are all so identified by their authors. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the Fabulist in the Fable

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Fabulist in the Fable Book A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Classics by Kristin Leilani Mann 2015 © Copyright by Kristin Leilani Mann 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERETATION The Fabulist in the Fable Book by Kristin Leilani Mann Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Kathryn Anne Morgan, Co-Chair Professor Amy Ellen Richlin, Co-Chair Four fable books survive from Greco-Roman antiquity: (1) the Life and Fables of Aesop (1st-2nd century CE), a collection of Greek prose fables; (2) Phaedrus’s Fabulae Aesopiae (1st century CE), a collection of Latin verse fables; (3) Babrius’s Μυθίαμβοι Αἰσώπειοι (1st century CE), a collection of Greek verse fables; and (4) Avianus’s Fabulae (4th-5th century CE), a collection of Latin verse fables. The thesis of this dissertation is that in each of these fable collections, the fabulist’s presence in the fable book – his biography, his self-characterizations, and his statements of purpose – combine to form a hermeneutic frame through which the fables may be interpreted. Such a frame is necessary because the fable genre is by nature multivalent: fables may be interpreted in many different ways, depending on their context. For embedded fables (that is, fables embedded in a larger narrative or speech), the fable’s immediate context influences the fable’s interpretation. In the fable books, however, there is no literary context; the ii fables stand as isolated narratives. The fabulist himself, I argue, takes the place of this missing context, and thus provides the reader with an interpretive framework. -

Suetonius the Life of Tiberius Translated by Alexander

SUETONIUS THE LIFE OF TIBERIUS TRANSLATED BY ALEXANDER THOMSON, M.D. REVISED AND CORRECTED BY T. FORESTER, ESQ., A.M. VITA TIBERI I. The patrician family of the Claudii (for there was a plebeian family of the same name, no way inferior to the other either in power or dignity) came originally from Regilli, a town of the Sabines. They removed thence to Rome soon after the building of the city, with a great body of their dependants, under Titus Tatius, who reigned jointly with Romulus in the kingdom; or, perhaps, what is related upon better authority, under Atta Claudius, the head of the family, who was admitted by the senate into the patrician order six years after the expulsion of the Tarquins. They likewise received from the state, lands beyond the Anio for their followers, and a burying-place for themselves near the capitol [284]. After this period, in process of time, the family had the honour of twenty-eight consulships, five dictatorships, seven censorships, seven triumphs, and two ovations. Their descendants were distinguished by various praenomina and cognomina [285], but rejected by common consent the praenomen of (193) Lucius, when, of the two races who bore it, one individual had been convicted of robbery, and another of murder. Amongst other cognomina, they assumed that of Nero, which in the Sabine language signifies strong and valiant. II. It appears from record, that many of the Claudii have performed signal services to the state, as well as committed acts of delinquency. To mention the most remarkable only, Appius Caecus dissuaded the senate from agreeing to an alliance with Pyrrhus, as prejudicial to the republic [286]. -

2017 UVA Classics Day Upper Level ROUND ONE

2017 UVA Classics Day Upper Level ROUND ONE 1. TOSSUP: Which scholar from Reate had established the founding date of Rome, had been honored with the corona navalis, and had written an exhaustive grammar book on the Latin language, in which only six out of 25 books survived? A: (Marcus Terentius) Varro BONUS: Give the name of the aforementioned work of Varro. A: De Linguā Latinā 2. TOSSUP: What centaur attempted to flee across a river carrying Deianeira, but was fatally shot by her husband Heracles? A: Nessus BONUS: What woman was the war prize who prompted Deianeira to give her husband a garment covered in Nessus’ blood? A: Iole 3. TOSSUP: Quid Anglice significat “lucus?” A: Grove BONUS: Quid Anglice significat “scopulus?” A: Cliff/crag/rock 4. TOSSUP: What use of the subjunctive is used in the following sentence? ‘Who is is that does not like bees?’ A: Relative Clause of Characteristic BONUS: Please translate that sentence into Latin. A: Quis est qui non apes amet?/Quis est cui apes non placeant 5. TOSSUP: Yeezus is not the first to have claimed, "I am a god". Which sandal-wearing emperor preferred to be referred to as "Neos Helios" or a sun god? A: Caligula BONUS: Divine intervention, Romans would have us think, goes back to the very origins of Rome. What is the name of the nymph who supposedly inspired Numa Pompilius to institute many of Rome's religious practices? A: Egeria *PAUSE FOR SCORE UPDATE* 6. TOSSUP: From what Latin adjective, with what meaning is the English word “Mature” ultimately derived? A: Maturus – Early/Ripe/Mature BONUS: What English adjective, derived from the same word, means “reserved or shy?” A: Demure 7.