Pitcher, Ronald Syme and Ovid's Road Not Taken

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Alexander Robinson, Jr. Memorial Lecture

DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS 48 College Street, Box 1856 Macfarlane House Providence, RI 02912 Phone: 401.863.1267 Fax: 401.863.7484 CHARLES ALEXANDER ROBINSON, JR. MEMORIAL LECTURE 1. October 14, 1965 “Vitruvius and the Greek House” • Richard Stillwell, Princeton University 2. November 15, 1966 “Second Thoughts in Greek Tragedy” • Bernard M. W. Knox 3. March 23, 1967 “Fiction and Fraud in the Late Roman Empire” • Sir Ronald Syme 4. November 29, 1967 “The Espionage-Commando Operation in Homer” • Sterling Dow, Harvard University 5. November 21, 1968 “Uses of the Past” • Gerald F. Else, University of Michigan 6. November 5, 1969 “Marcus Aurelius and Athens” • James H. Oliver, Johns Hopkins University 7. March 1, 1971 “Between Literacy and Illiteracy: An Aspect of Greek Culture in Egypt” • Herbert C. Youtie, University of Michigan 8. October 27, 1971 “Psychoanalysis and the Classics” • J. P. Sullivan, SUNY Buffalo 9. November 14, 1972 “The Principles of Aeschylean Drama” • C. J. Herington, Yale University 10. October 30, 1973 “Alexander and the Historians” • Peter Green, University of Texas, Austin 11. November 6, 1974 “The Emotional Power of Greek Tragedy” • W. Bedell Stanford, Trinity College, Dublin 12. March 10, 1976 “Personality in Classical Greek Sculpture” • George M.A. Hanfmann, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University 13. March 28, 1977 “The Odyssey” • John M. Finley, Harvard University 14. November 21, 1978 “Community of Men and Gods in Ancient Athens” • Homer A. Thompson, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton 15. April 23, 1979 “Oedipus’ Mother” • Anne Pippin Burnett, University of Chicago 16. March 17, 1980 “Rustic Urbanity: Roman Satirists in and outside Rome” • William S. -

The Last Generation of the Roman Republic Free Download

THE LAST GENERATION OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC FREE DOWNLOAD Erich S. Gruen | 615 pages | 01 Mar 1995 | University of California Press | 9780520201538 | English | Berkerley, United States Erich S. Gruen Gruen's argument is that the Republic was not in decay, and so not necessarily in need of "rescue" by Caesar Augustus and the institutions of the Empire. Audible 0 editions. I hate that. This massive, articulate work has stood the test of time, and, if not indispensable it is still highly regarded and a standard guide to the period. The method is hazardous and delusive. Appius Claudius Pulcher consul 54 BC. This article needs additional citations for verification. We know what it's like to be in the weeds with a chunk of the written word. You can help The Last Generation of the Roman Republic by expanding it. Namespaces Article Talk. Open Preview See a Problem? Namespaces Article Talk. Published February 28th by University of California Press first published Philistine comment aside, he had a point - this book was work. I often found the real chestnuts of information were often contained in The Last Generation of the Roman Republic footnotes. He systematically challenges every theory in order to reveal their weaknesses and to validate his own thesis. Get it now! Wiseman Erich S. It's an important work, up there with Syme, the review spurred me to want to buy it--again, I had a copy once and it's disappeared after several moves. In this case The Last Generation of the Roman Republic others, recent historical research has supported some of the theories that Gruen challenged. -

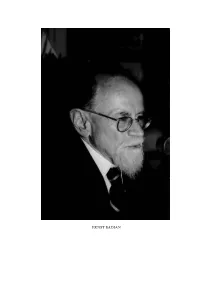

In This, One of the Last Photographs Taken of Sir Ronald Syme OM, He Is

In this, one of the last photographs taken of Sir Ronald Syme OM, he is shown with Sir Isaiah Berlin OM and Lord Franks OM on 16 June 1989 before the Foundation Dinner at Wolfson College, Oxford, of which he was an Extraordinary Fellow from his retirement from the Camden Chair in 1970 until his death on 4 September 1989. Copyright, Times Newspapers SIR RONALD SYME i903-i989 ... non Mud culpa senectae sed labor intendens animique in membra vigentis imperium vigilesque suo pro Caesare curae dulce o/>«s*(Statius, Silvae 1.4, cf. RP v, 514) The death of Sir Ronald Syme on 4 September 1989 has deprived the Roman Society of its most distinguished member and the world of classical scholarship of its foremost historian. Elected to life membership of the Society in 1929 when he became a Fellow of Trinity College, Oxford, Syme joined the Editorial Committee in 1931, became a Vice- President in 1938, and served an extended term as President from 1948 to 1952. This was a crucial period during which the arrangements were made for housing the Hellenic and Roman Societies and their Joint Library in the new Institute of Classical Studies in Gordon Square. Thereafter Syme remained an active member of the Society, whose secretaries, as Patricia Gilbert attests, valued him as a wise and accessible counsellor. He also lectured for the Society and advised Editors of this Journal, in which many articles of his continued to appear. Ronald Syme died three days before the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of the Roman Revolution, at the age of eighty-six. -

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011 THE ANCIENT HISTORIAN ERNST BADIAN was born in Vienna on 8 August 1925 to Josef Badian, a bank employee, and Salka née Horinger, and he died after a fall at his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, on 1 February 2011. He was an only child. The family was Jewish but not Zionist, and not strongly religious. Ernst became more observant in his later years, and received a Jewish funeral. He witnessed his father being maltreated by Nazis on the occasion of the Reichskristallnacht in November 1938; Josef was imprisoned for a time at Dachau. Later, so it appears, two of Ernst’s grandparents perished in the Holocaust, a fact that almost no professional colleague, I believe, ever heard of from Badian himself. Thanks in part, however, to the help of the young Karl Popper, who had moved to New Zealand from Vienna in 1937, Josef Badian and his family had by then migrated to New Zealand too, leaving through Genoa in April 1939.1 This was the first of Ernst’s two great strokes of good fortune. His Viennese schooling evidently served Badian very well. In spite of knowing little English at first, he so much excelled at Christchurch Boys’ High School that he earned a scholarship to Canterbury University College at the age of fifteen. There he took a BA in Classics (1944) and MAs in French and Latin (1945, 1946). After a year’s teaching at Victoria University in Wellington he moved to Oxford (University College), where 1 K. R. Popper, Unended Quest: an Intellectual Autobiography (La Salle, IL, 1976), p. -

“That Sickly and Sinister Youth”: the First Considerations of Syme on Octavian As a Historical Figure Autor(Es): García

“That sickly and sinister youth”: the first considerations of Syme on Octavian as a historical figure Autor(es): García Vivas, Gustavo Alberto Publicado por: Centro de História da Universidade de Lisboa URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/38929 DOI: DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/0871-9527_24_5 Accessed : 25-Sep-2021 20:33:32 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt “THAT SICKLY AND SINISTER YOUTH”: THE FIRST CONSIDERATIONS OF SYME ON OCTAVIAN AS A HISTORICAL FIGURE* GUSTAVO ALBERTO GARCÍA VIVAS University of La Laguna [email protected] To my mother In memoriam Abstract: Throughout 1934, Ronald Syme published several articles in which he set out his initial ideas about Octavian, the future emperor Augustus. -

Winter Quarter, but Registration Checks (Payable to 5:30, in the Lassen Room at the San Francisco Hilton Hotel

ASSOCIATION OF NEWSLETTER ANCIENT HISTORIANS No. 62 December 1993 NOTICES sia, (2) problems in ancient social history (especially sexuality, Calendar-year 1994 dues are due on January 1. family, demography), and (3) the Christianization of the Roman Paid-up members of AAH are entitled to a $12.80 (20% dis• Empire. We hope that each session will include a paper provid• count) annual subscription rate to the American Journal of ing a broad introduction to recent research and controversies. Ancient History. Write to: AJAH, Dept. of History, Robinson Two-page abstracts for papers of about twenty or thirty minutes Hall, Harvard Univ., Cambridge, MA 02138. (Please do not length should be sent to Robert Drews or Thomas J. McGinn no direct questions concerning AJAH to the Secretary-Treasurer; the later than October 1, 1994 (we hope to have a program com• journal is an entirely separate operation.) posed by December 1). Address: Dept. of Classical Studies, Van• Members with new books out, honors, or positions should derbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235. FAX 615-343-7261. E• notify me at the return address on the Newsletter (through April Mail [email protected]. 1994, that is; subsequently notify my successor). What is report• ed is largely determined by what you submit. Jack Cargill PUBLICATIONS OF THE AAH Copies of PAAH 4 = Carol G. Thomas, Myth Becomes Histo• SECRETARY·TREASURER ELECTION ry: Pre-Classical Greece must be purchased from Regina Books, A new Secretary-Treasurer is to be elected at the AAH meet• P.O. Box 280, Claremont, CA 91711. Similarly, anyone interest• ing in Dayton in May 1994, at which time my own service reach• ed must deal directly with University Press of America, 720 es its constitutional two-term limit. -

Download PDF Bibliography

Select Bibliography of Works Relating to Prosopography Presented here is a selection of around 500 titles that chart the development of prosopography since the late nineteenth century as a method used by historians of all periods. There is no optimal way of presenting such a list – subject matter and periods frequently overlap – but with a little repetition, crossreferencing and self explanatory headings, it is hoped that the user will find what he wants relatively easily. All the titles considered fundmental are listed here. The first section is chronological, and the second methodological. As befits the history of this development, the section on the Ancient World is the longest. Other sections are: Byzantium, Medieval World (including Islam), Modern, Method, Biographical Method, Onomastics, Data Modelling, Social Network Analysis. I. Prosopography by Period 1.The Ancient World Aleshire, S. B., Asklepios at Athens: Epigraphic and Prosopographic Essays on the Athenian Healing Cults (Amsterdam, 1991) Alföldy, G., Fasti Hispanienses. Senatorische Reichsbeamte und Offiziere in den spanischen Provinzen des römischen Reiches von Augustus bis Diokletian (Wiesbaden, 1969) ——, Konsulat und Senatorenstand unter den Antoninen. Prosopographische Untersuchungen zur senatorischen Führungsschicht (Bonn, 1977) ——, ‘Consuls and consulars under the Antonines: prosopography and history’, Ancient Society, 7 (1976), 263–99 Andermahr, A. M., Totus in praediis. Senatorischer Grundbesitz in Italien in der Frühen und Hohen Kaiserzeit (Bonn, 1998) Babelon, E., Description historique et chronologique des monnaies de la République Romaine, vulgairement appellées monnaies consulaires (Paris, 1885–6) Badian, E., ‘The scribae of the Roman Republic’, Klio, 71 (1989), 582–603. Bagnall, R. S., Consuls of the Later Roman Empire (Atlanta GA., 1987) Barnes, T. -

Select Correspondence of Ronald Syme, 1927–1939 Edited by Anthony R

Select Correspondence of Ronald Syme, ����–���� Edited by Anthony R. Birley HCS History of Classical Scholarship Supplementary Volume 1 History of Classical Scholarship Editors Lorenzo CALVELLI (Venezia) Federico SANTANGELO (Newcastle) Editorial Board Luciano CANFORA Marc MAYER (Bari) (Barcelona) Jo-Marie CLAASSEN Laura MECELLA (Stellenbosch) (Milano) Massimiliano DI FAZIO Leandro POLVERINI (Pavia) (Roma) Patricia FORTINI BROWN Stefan REBENICH (Princeton) (Bern) Helena GIMENO PASCUAL Ronald RIDLEY (Alcalá de Henares) (Melbourne) Anthony GRAFTON Michael SQUIRE (Princeton) (London) Judith P. HALLETT William STENHOUSE (College Park, Maryland) (New York) Katherine HARLOE Christopher STRAY (Reading) (Swansea) Jill KRAYE Daniela SUMMA (London) (Berlin) Arnaldo MARCONE Ginette VAGENHEIM (Roma) (Rouen) Copy-editing & Design Thilo RISING (Newcastle) Select Correspondence of Ronald Syme, 1927–1939 Edited by Anthony R. Birley Published by History of Classical Scholarship Newcastle upon Tyne and Venice Posted online at hcsjournal.org in April 2020 The publication of this volume has been co-funded by the Department of Humanities of the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice and the School of History, Classics and Archaeology of Newcastle University Submissions undergo a double-blind peer-review process This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence Any part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission provided that the source is fully credited ISBN 978-1-8380018-0-3 © 2020 Anthony R. Birley History of Classical Scholarship Edited by Lorenzo Calvelli and Federico Santangelo SUPPLEMENTARY VOLUMES 1. Select Correspondence of Ronald Syme, 1927–1939 Edited by Anthony R. Birley (2020) Informal queries and new proposals may be sent to [email protected] or [email protected]. -

Ernst Badian Was Spread Upon the Permanent Records of the Faculty

At a meeting of the FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES on December 2, 2014, the following tribute to the life and service of the late Ernst Badian was spread upon the permanent records of the Faculty. ERNST BADIAN BORN: August 8, 1925 DIED: February 1, 2011 Ernst Badian, John Moors Cabot Professor of History, Emeritus, was one of the world’s most eminent ancient historians. Appointed to the Department of History in 1971, and by courtesy a voting member of the Department of the Classics in 1973, he became emeritus in 1998. Born in Vienna, he and his parents fled the mounting persecution of the Jews in 1938 and settled in New Zealand. Badian received a B.A. with first-class honors and an M.A. from then Canterbury University College, Christchurch (University of New Zealand); he took a B.A. from Oxford University with first-class honors, and wrote his dissertation under the great Roman historian Sir Ronald Syme, two volumes of whose papers he would later edit. From the dissertation emerged his Foreign Clientelae, 274–70 B.C. (1958), still recognized as a classic study of how the social institution of patrons and clients shaped early Roman imperialism in and beyond Italy and molded the politics of the later Republic. This theme resulted in major studies: Roman Imperialism in the Late Republic (1967) and Publicans and Sinners (1972). Mastery of the primary sources, particularly inscriptions, and technically intricate and rigorous analysis of fragmentary prosopographical evidence characterized Badian’s approach. From scrappy biographical information about many individuals, he deduced political and institutional patterns that greatly deepened our understanding of the ancient world. -

Latin Historiography | University of Glasgow

09/30/21 Latin Historiography | University of Glasgow Latin Historiography View Online 63 items Prescribed Texts (3 items) Titi Livi ab urbe condita: Tomus 1 - R. M. Ogilvie, Livy, 1974 Book Livy, book 1 - H. E. Gould, J. L. Whiteley, Livy, 1987 Book | Suggested for Student Purchase Tacitus Annals book IV - Cornelius Tacitus, Ronald H. Martin, A. J. Woodman, 1989 Book | Suggested for Student Purchase Preliminary Texts (7 items) Latin historians - Christina Shuttleworth Kraus, A. J. Woodman, 1997 Book | Suggested for Student Purchase Livy, book 1 - H. E. Gould, J. L. Whiteley, Livy, 1987 Book | Suggested for Student Purchase Tacitus Annals book IV - Cornelius Tacitus, Ronald H. Martin, A. J. Woodman, 1989 Book | Suggested for Student Purchase The early history of Rome: books I-V of the History of Rome from its foundation - Aubrey De Sélincourt, Livy, 1960 Book | One possible translation of Livy book 1 to read before the start of course. Alternatively, read the translation online at www.perseus.tufts.edu Livy: Vols.1-5: Books 1-22 - B. O. Foster, Livy, 1919-1929 Book | One possible translation of Livy book 1 to read before the start of course. Alternatively, read the translation online at www.perseus.tufts.edu The annals of imperial Rome - Cornelius Tacitus, Michael Grant, 1996 Book | One possible translation of Tacitus Annals 4 to read before the start of course. Alternatively, read the translation online at www.perseus.tufts.edu Tacitus in five volumes: 1: Agricola ; Germania ; Dialogus - Cornelius Tacitus, Cornelius Tacitus, Cornelius Tacitus, Maurice Hutton, R. M. Ogilvie, William Peterson, E. H. Warmington, Michael Winterbottom, 1970 Book | One possible translation of Tacitus Annals 4 to read before the start of course. -

The Augustan Aristocracy | Ronald Syme | 1986

The Augustan Aristocracy | Ronald Syme | 1986 Clarendon Press, 1986 | 0198148593, 9780198148593 | Ronald Syme | 1986 | The Augustan Aristocracy | While the monarchy established by Caesar Augustus has attracted much scholarly attention, far less has been said about the reemergence of the old nobility at that time after years of civil war. One clear reason for this has been the lack of reliable evidence from the period. This book goes backward to the early years of the 1st century B.C. and forward to the reign of Nero in search of documentation of the Augustan aristocracy. Syme draws particularly on the Annals of Tacitus to cover 150 years in the history of Roman families, chronicling their splendor and success, as well as their subsequent fall within the embrace of the dynasty. file download ziku.pdf Finder of the Mississippi | Ronald Syme | 96 pages | 1957 | DeSoto | Explorers The 1953 | The Windward Islands, Volume 3 | UCAL:B3615323 | Windward Islands (Jurisdiction) | Ronald Syme The Augustan Aristocracy pdf file Sallust | History | With this classic book, Sir Ronald Syme became the first historian of the twentieth century to place Sallustwhom Tacitus called the most brilliant Roman historianin his | 433 pages | Jun 5, 2002 | ISBN:0520929101 | Ronald Syme The Augustan Aristocracy pdf download 19 pages | UCAL:B4569103 | Ronald Syme | The story of British roads | Reference Ronald Syme, Werner Forman | The travels of Captain Cook | 1971 | Biography & Autobiography | 179 pages | ISBN:0070626502 pdf Tacitus | 1958 | Tacitus | Ronald Syme pdf -

World of Classical Rome Lecturer: Alexander Evers Dphil (Oxon) ([email protected])

LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO ROME CENTER AUTUMN SEMESTER 2018 – CLST 276/ROST 276 THE WORLD OF CLASSICAL ROME LECTURER: ALEXANDER EVERS DPHIL (OXON) ([email protected]) COURSE DESCRIPTION AND ABSTRACT Rome – Umbilicus Mundi, the navel of the world, the centre of civilisation, by far the greatest city in Antiquity. The “most splendid of splendid cities” counted approximately one million inhabitants in its hey- day. Lavish provisions of food and wine, as well as spectacles and various forms of urban decoration, magnificent temples and public buildings were pretty much the norm. Public baths, gardens, libraries, circuses, theatres and amphitheatres gave access to all the citizens of Rome. An elaborate network of roads and aqueducts, well-maintained throughout the centuries, all led to the Eternal City. It must have appeared at the time that Rome would never end! The World of Classical Rome takes us on a journey, a journey through time. If you always thought space to be the final frontier, then you’re wrong: time is! This course investigates the historical development of the Roman people through study of their history, politics, society and culture especially in the 1st centuries BC and AD, the turning points of Republican and Imperial Rome. Actually, speaking of turning points, the last phrase of the previous, first paragraph, might be a bit misleading… At least to a contemporary Roman at the time… Because to some of those old chaps, the Roman Republic seemed to be in grave danger… And with the Republic, Rome… With Rome, the world… Think Star