Scott Pilgrim Vs the Future of Comics Publishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

Microsoft Visual Basic

$ LIST: FAX/MODEM/E-MAIL: aug 23 2021 PREVIEWS DISK: aug 25 2021 [email protected] for News, Specials and Reorders Visit WWW.PEPCOMICS.NL PEP COMICS DUE DATE: DCD WETH. DEN OUDESTRAAT 10 FAX: 23 augustus 5706 ST HELMOND ONLINE: 23 augustus TEL +31 (0)492-472760 SHIPPING: ($) FAX +31 (0)492-472761 oktober/november #557 ********************************** __ 0079 Walking Dead Compendium TPB Vol.04 59.99 A *** DIAMOND COMIC DISTR. ******* __ 0080 [M] Walking Dead Heres Negan H/C 19.99 A ********************************** __ 0081 [M] Walking Dead Alien H/C 19.99 A __ 0082 Ess.Guide To Comic Bk Letterin S/C 16.99 A DCD SALES TOOLS page 026 __ 0083 Howtoons Tools/Mass Constructi TPB 17.99 A __ 0019 Previews October 2021 #397 5.00 D __ 0084 Howtoons Reignition TPB Vol.01 9.99 A __ 0020 Previews October 2021 Custome #397 0.25 D __ 0085 [M] Fine Print TPB Vol.01 16.99 A __ 0021 Previews Oct 2021 Custo EXTRA #397 0.50 D __ 0086 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.01 14.99 A __ 0023 Previews Oct 2021 Retai EXTRA #397 2.08 D __ 0087 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.02 14.99 A __ 0024 Game Trade Magazine #260 0.00 N __ 0088 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.03 14.99 A __ 0025 Game Trade Magazine EXTRA #260 0.58 N __ 0089 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.04 14.99 A __ 0026 Marvel Previews O EXTRA Vol.05 #16 0.00 D __ 0090 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.05 14.99 A IMAGE COMICS page 040 __ 0091 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.06 16.99 A __ 0028 [M] Friday Bk 01 First Day/Chr TPB 14.99 A __ 0092 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.07 16.99 A __ 0029 [M] Private Eye H/C DLX 49.99 A __ 0093 [M] Sunstone Book 01 H/C 39.99 A __ 0030 [M] Reckless -

SEP 2010 Order Form PREVIEWS#264 MARVEL COMICS

Sep10 COF C1:COF C1.qxd 8/11/2010 12:22 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 11 SEP 2010 SEP E COMIC H T SHOP’S CATALOG COF C2:Layout 1 8/6/2010 1:36 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page Sept:gem page v18n1.qxd 8/12/2010 8:55 AM Page 1 KULL: THE HATE WITCH #1 (OF 4) BATMAN: DARK HORSE COMICS THE DARK KNIGHT #1 DC COMICS HELLBOY: DOUBLE FEATURE OF EVIL DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN, INC. #1 THE WALKING DEAD DC COMICS VOL. 13: TOO FAR GONE TP IMAGE COMICS MAGAZINE GEM OF THE MONTH DUNGEONS & DRAGONS #1 IDW PUBLISHING ..UTOPIAN #1 IMAGE COMICS WIZARD #232 WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT GENERATION HOPE #1 MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 8/12/2010 2:47 PM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS ELMER GN G AMAZE INK/SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS NIGHTMARES & FAIRY TALES: ANNABELLE‘S STORY #1 G AMAZE INK/SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS S.E. HINTON‘S PUPPY SISTER GN G BLUEWATER PRODUCTIONS STAN LEE‘S TRAVELER #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 1 DARKWING DUCK VOLUME 1: THE DUCK KNIGHT RETURNS TP G BOOM! STUDIOS LADY DEATH ORIGINS VOLUME 1 TP/HC G BOUNDLESS COMICS VAMPIRELLA #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT KEVIN SMITH‘S GREEN HORNET VOLUME 1: SINS OF THE FATHER TP G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT ACME NOVELTY LIBRARY VOLUME 20 HC G DRAWN & QUARTERLY NORTH GUARD #1 G MOONSTONE LAST DAYS OF AMERICAN CRIME TP G RADICAL PUBLISHING ATOMIC ROBO AND THE DEADLY ART OF SCIENCE #1 G RED 5 COMICS BOOKS & MAGAZINES COMICS SHOP SC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES KRAZY KAT AND THE ART OF GEORGE HERRIMAN HC G COMICS SPYDA CREATIONS: STUDY OF THE SCULPTURAL METHOD SC G HOW-TO 2 STAR TREK: USS ENTERPRISE HAYNES OWNER‘S MANUAL HC G STAR -

Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2017 To Start, Continue, and Conclude: Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing Gabriel E. Romaguera University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Romaguera, Gabriel E., "To Start, Continue, and Conclude: Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing" (2017). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 619. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/619 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO START, CONTINUE, AND CONCLUDE: FOREGROUNDING NARRATIVE PRODUCTION IN SERIAL FICTION PUBLISHING BY GABRIEL E. ROMAGUERA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF Gabriel E. Romaguera APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Valerie Karno Carolyn Betensky Ian Reyes Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 Abstract This dissertation explores the author-text-reader relationship throughout the publication of works of serial fiction in different media. Following Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of authorial autonomy within the fields of cultural production, I trace the outside influence that nonauthorial agents infuse into the narrative production of the serialized. To further delve into the economic factors and media standards that encompass serial publishing, I incorporate David Hesmondhalgh’s study of market forces, originally used to supplement Bourdieu’s analysis of fields. -

MAD SCIENCE! Ab Science Inc

MAD SCIENCE! aB Science Inc. PROGRAM GUIDEBOOK “Leaders in Industry” WARNING! MAY CONTAIN: Vv Highly Evil Violations of Volatile Sentient :D Space-Time Materials Robots Laws FOOT table of contents 3 Letters from the Co-Chairs 4 Guests of Honor 10 Events 15 Video Programming 18 Panels & Workshops 28 Artists’ Alley 32 Dealers Room 34 Room Directory 35 Maps 41 Where to Eat 48 Tipping Guide 49 Getting Around 50 Rules 55 Volunteering 58 Staff 61 Sponsors 62 Fun & Games 64 Autographs APRIL 2-4, 2O1O 1 IN MEMORY OF TODD MACDONALD “We will miss and love you always, Todd. Thank you so much for being a friend, a staffer, and for the support you’ve always offered, selflessly and without hesitation.” —Andrea Finnin LETTERS FROM THE CO-CHAIRS Anime Boston has given me unique growth Hello everyone, welcome to Anime Boston! opportunities, and I have become closer to people I already knew outside of the convention. I hope you all had a good year, though I know most of us had a pretty bad year, what with the economy, increasing healthcare This strengthening of bonds brought me back each year, but 2010 costs and natural disasters (donate to Haiti!). At Anime Boston, is different. In the summer of 2009, Anime Boston lost a dear I hope we can provide you with at least a little enjoyment. friend and veteran staffer when Todd MacDonald passed away. We’ve been working long and hard to get composer Nobuo When Todd joined staff in 2002, it was only because I begged. Uematsu, most famous for scoring most of the music for the Few on staff imagined that our three-day convention was going Final Fantasy games as well as other Square Enix games such to be such an amazing success. -

Game Developer

THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE vo L 1 8 N o 9 o c T o b er 2011 INSIDE: R ea c ti v E game ar c hite c tures w ith R x d e pa r T m e NTS 2 GAME PLAN By Brandon Sheffield [EDITORIAL] Interactive History CoNTeNTS.1011 volUme 18 NUmBer 09 4 HEADS UP DISPLAY [ ne w S ] New games for vintage consoles, Michael Jackson visits Sega, and ASCII Animator released. 27 TOOL BOX By David Hellman [REVIE w ] Corel Painter 12 p o ST m o r T e m 34 THE INNER PRODUCT By Peter Drescher [PROGRAMMING] 20 bulletstorm Programming FMOD for Android BulleTsTorm is a colorful skillshot-fest that took 3.5 years to make. It 40 DESIGN OF THE TIMES By Soren Johnson [DESIGN] didn't perform quite to expectations at retail, but the experiment was Taking Feedback by all other metrics a success. This straight-shooting design-focused postmortem discusses everything from emergent feature discoveries 42 PIXEL PUSHER By Steve Theodore [ART] to downloadable demo woes. By Adrian Chmielarz Get The Memo 44 the business By Kim Pallister [ business ] F e aTU r e S Efficiency...For Whom? 6 game changers 46 GDC jobs By Mathew Kumar [ career ] The game industry is a dynamic and fluidly-changing one. But who Recruitment at GDC Online (and what) are the companies and concepts that are shaping the 47 AURAL FIXATION By Jesse Harlin [SOUND] game industry today? Our answer to this question is 20 companies, Separation Anxiety processes, and concepts that are changing the game. -

PDF UTC Schedule

Flights of Foundry 2021 A Art/Illustration D Audio/Podcasting C Comics F Guest of Honor I Industry Biz L Limited Access P Poetry O Prose T Translation W Writing APRIL 16 • FRIDAY 14:00 – 14:25 W Diane Turnshek - Reading Courtyard Speakers: Diane Turnshek I'll read shorter and shorter fiction as I walk around to different spots in my very small house until I tell my story with a negative word count. Small is beautiful! Happy to welcome you folks to my tiny house tour and tiny reading. 15:00 – 15:25 W Gregory Wilson - Reading Courtyard Speakers: Gregory Wilson From my most recent bio--please let me know if you need more information! Gregory A. Wilson is Professor of English at St. John's University in New York City, where he teaches creative writing, speculative fiction, and various other courses in literature. In addition to academic work, he is the author of the epic fantasy The Third Sign, the graphic novel Icarus, the dark fantasy Grayshade, and the D&D adventure/sourcebook Tales and Tomes from the Forbidden Library. He also has short stories in a number of anthologies, and has several projects forthcoming in 2021. He co- hosts the critically acclaimed actual play Speculate! The Podcast for Writers, Readers, and Fans (speculatesf.com) podcast, is a member of the Gen Con Writers' Symposium and co-coordinator of the Origins Library, and is a regular panelist at conferences nationally and internationally. He is the lead vocalist and trumpet player for The Road, a long running progressive rock band with three albums to its credit, and is the lead writer for Chosen Heart, a video game currently in production. -

2010 1:22 PM Page 1

April 10 COF C1:COF C1.qxd 3/18/2010 1:22 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 10APR 2010 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG Project7:Layout 1 3/15/2010 1:35 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page Apr:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/18/2010 2:07 PM Page 1 PREDATORS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUZZARD #1 DARK HORSE COMICS GREEN ARROW #1 DC COMICS SUPERMAN #700 DC COMICS JURASSIC PARK: REDEMPTION #1 IDW PUBLISHING HACK/SLASH: MY FIRST MANIAC #1 MAGAZINE GEM OF THE MONTH IMAGE COMICS THE BULLETPROOF COFFIN #1 IMAGE COMICS WIZARD MAGAZINE #226 THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #634 MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/18/2010 2:14 PM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS 1 THE ROYAL HISTORIAN OF OZ #1 G AMAZE INK/ SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS CRITICAL MILLENNIUM #1 G ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT LLC DARKWING DUCK: THE DUCK KNIGHT RETURNS #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS DISNEY‘S ALICE IN WONDERLAND GN/HC G BOOM! STUDIOS RED SONJA #50 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT STARGATE: DANIEL JACKSON #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 GHOSTOPOLIS SC/HC G GRAPHIX THE WHISPERS IN THE WALLS #1 G HUMANOIDS INC STARDROP VOLUME 1 GN G I BOX PUBLISHING KRAZY KAT: A CELEBRATION OF SUNDAYS HC G SUNDAY PRESS BOOKS SIMON & KIRBY SUPERHEROES HC G TITAN PUBLISHING THE PLAYWRIGHT HC G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS CHARMED #1 G ZENESCOPE ENTERTAINMENT INC BOOKS & MAGAZINES WILLIAM STOUT: HALLUCINATIONS SC/HC G ART BOOKS 2 SUCK IT, WONDER WOMAN! MISADVENTURES OF A HOLLYWOOD GEEK G HUMOR ASLAN: THE PIN-UP SC G INTERNATIONAL STAR WARS: THE OFFICIAL FIGURINE COLLECTION MAGAZINE G STAR WARS TOYFARE #156 G WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT CALENDARS 2 BONE 2011 WALL CALENDAR G COMICS VINTAGE -

The Art of the Game: Issues in Adapting Video Games

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 4-2020 The Art of the Game: Issues in Adapting Video Games Sydney Baty University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Screenwriting Commons Baty, Sydney, "The Art of the Game: Issues in Adapting Video Games" (2020). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 167. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/167 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE ART OF THE GAME: ISSUES IN ADAPTING VIDEO GAMES By Sydney K. Baty A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of the Arts Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Tom Gannon Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2020 THE ART OF THE GAME: ISSUES IN ADAPTING VIDEO GAMES Sydney K. Baty, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2020 Advisor: Tom Gannon On the face of things, movies and video games are similar mediums. Both engage extensively in visuals and audio, both can indulge in speculative fiction, and there is a healthy amount of sharing of inspiration and content. However, this does not guarantee successful adaptations from one form to another. -

Geek Cultures: Media and Identity in the Digital Age Jason Tocci University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2009 Geek Cultures: Media and Identity in the Digital Age Jason Tocci University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Other Communication Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Tocci, Jason, "Geek Cultures: Media and Identity in the Digital Age" (2009). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 953. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/953 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/953 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Geek Cultures: Media and Identity in the Digital Age Abstract This study explores the cultural and technological developments behind the transition of labels like 'geek' and 'nerd' from schoolyard insults to sincere terms identity. Though such terms maintain negative connotations to some extent, recent years have seen a growing understanding that "geek is chic" as computers become essential to daily life and business, retailers hawk nerd apparel, and Hollywood makes billions on sci-fi, hobbits, and superheroes. Geek Cultures identifies the experiences, concepts, and symbols around which people construct this personal and collective identity. This ethnographic study considers geek culture through multiple sites and through multiple methods, including participant observation at conventions and local events promoted as "geeky" or "nerdy"; interviews with fans, gamers, techies, and self-proclaimed outcasts; textual analysis of products produced by and for geeks; and analysis and interaction online through blogs, forums, and email. -

Zines and Minicomics Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c85t3pmt No online items Guide to the Zines and Minicomics Collection Finding Aid Authors: Anna Culbertson and Adam Burkhart. © Copyright 2014 Special Collections & University Archives. All rights reserved. 2014-05-01 5500 Campanile Dr. MC 8050 San Diego, CA, 92182-8050 URL: http://library.sdsu.edu/scua Email: [email protected] Phone: 619-594-6791 Guide to the Zines and MS-0278 1 Minicomics Collection Guide to the Zines and Minicomics Collection 1985 Special Collections & University Archives Overview of the Collection Collection Title: Zines and Minicomics Collection Dates: 1985- Bulk Dates: 1995- Identification: MS-0278 Physical Description: 42.25 linear ft Language of Materials: EnglishSpanish;Castilian Repository: Special Collections & University Archives 5500 Campanile Dr. MC 8050 San Diego, CA, 92182-8050 URL: http://library.sdsu.edu/scua Email: [email protected] Phone: 619-594-6791 Access Terms This Collection is indexed under the following controlled access subject terms. Topical Term: American poetry--20th century Anarchism Comic books, strips, etc. Feminism Gender Music Politics Popular culture Riot grrrl movement Riot grrrl movement--Periodicals Self-care, Health Transgender people Women Young women Accruals: 2002-present Conditions Governing Use: The copyright interests in these materials have not been transferred to San Diego State University. Copyright resides with the creators of materials contained in the collection or their heirs. The nature of historical archival and manuscript collections is such that copyright status may be difficult or even impossible to determine. Requests for permission to publish must be submitted to the Head of Special Collections, San Diego State University, Library and Information Access. -

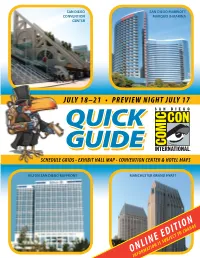

Quick Guide Is Online

SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO MARRIOTT CONVENTION MARQUIS & MARINA CENTER JULY 18–21 • PREVIEW NIGHT JULY 17 QUICKQUICK GUIDEGUIDE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • CONVENTION CENTER & HOTEL MAPS HILTON SAN DIEGO BAYFRONT MANCHESTER GRAND HYATT ONLINE EDITION INFORMATION IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE MAPu HOTELS AND SHUTTLE STOPS MAP 1 28 10 24 47 48 33 2 4 42 34 16 20 21 9 59 3 50 56 31 14 38 58 52 6 54 53 11 LYCEUM 57 THEATER 1 19 40 41 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE 36 30 SPONSOR FOR COMIC-CON 2013: 32 38 43 44 45 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE SPONSOR OF COMIC‐CON 2013 26 23 60 37 51 61 25 46 18 49 55 27 35 8 13 22 5 17 15 7 12 Shuttle Information ©2013 S�E�A�T Planners Incorporated® Subject to change ℡619‐921‐0173 www.seatplanners.com and traffic conditions MAP KEY • MAP #, LOCATION, ROUTE COLOR 1. Andaz San Diego GREEN 18. DoubleTree San Diego Mission Valley PURPLE 35. La Quinta Inn Mission Valley PURPLE 50. Sheraton Suites San Diego Symphony Hall GREEN 2. Bay Club Hotel and Marina TEALl 19. Embassy Suites San Diego Bay PINK 36. Manchester Grand Hyatt PINK 51. uTailgate–MTS Parking Lot ORANGE 3. Best Western Bayside Inn GREEN 20. Four Points by Sheraton SD Downtown GREEN 37. uOmni San Diego Hotel ORANGE 52. The Sofia Hotel BLUE 4. Best Western Island Palms Hotel and Marina TEAL 21. Hampton Inn San Diego Downtown PINK 38. One America Plaza | Amtrak BLUE 53. The US Grant San Diego BLUE 5.