Unlocking Australia's Language Potential: Profiles of 9 Key Languages in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Tree Change Without Leaving the City

Your tree change without leaving the city THIS IS THE PERFECT TIME TO PURCHASE INSPIRED BY THE BEAUTY OF ITS LUSH AN APARTMENT IN THE AREA, AND POTTS GREEN RURAL LIKE SETTING, TALLOWOOD IS HILL IS BANKSTOWN’S PREMIER LOCATION THE FINEST EXPRESSION OF LANDCOM’S AWARD-WINNING POTTS HILL COMMUNITY BANKSTOWN – A CITY OF PROGRESS Named after the majestic tree that forms its a superb selection of shopping centres, schools, centrepiece, Tallowood borders Canal Park and sports facilities and golf courses. the picturesque heritage-protected Sydney Water bushland. Only minutes from Lidcombe and Away from the stresses of city living yet only 20km Bankstown yet seemingly a world away from west of Sydney CBD, Potts Hill balances a country the hustle and bustle of city life. like ambience with excellent transport and road links. Birrong station is 900m away and one stop from Uniting five buildings around a central landscaped Bankstown Station and the proposed Sydney Metro garden and a series of pocket parks, Tallowood CBD express train. promotes a relaxed lifestyle that embraces the outdoors. Feel connected with nature and the Identified in 2015 by the NSW Government as a ‘Major surrounding community with an abundance of Centre’, with a significant focus on infrastructure light-filled open space in between. investment and intensive growth over the next 20 years combined with the expansion of the North West Tallowood offers a rare opportunity to invest in Rail Link (Sydney Rapid Transit – Sydney Metro) a lifestyle of comfort. Experience the beauty of nature from Chatswood to Bankstown, and the planned 15 with the convenience of city living virtually at your trains per hour from Bankstown to the CBD, the area doorstep. -

Inquiry Into Agricultural Education and Training in Victoria

Education and Training Committee Inquiry into agricultural education and training in Victoria ORDERED TO BE PRINTED November 2012 by Authority Victorian Government Printer Parliamentary paper No.196 Session 2010–2012 Parliament of Victoria Education and Training Committee Inquiry into agricultural education and training in Victoria This report is also available at www.parliament.vic.gov.au/etc Printed on 100% recycled paper ISBN 978-0-9871154-2-3 ISBN 978-0-9871154-3-0 Electronic ii Contents Contents .............................................................................................................................. iii List of figures ...................................................................................................................... xi List of case studies ........................................................................................................... xiii Committee membership .................................................................................................... xv Functions of the Committee ............................................................................................. xvi Terms of reference ............................................................................................................ xvi Chair’s foreword .............................................................................................................. xvii Executive summary ......................................................................................................... xix List of -

Bankstown District Amateur Football Association

Bankstown District Amateur Football Association Minutes of the 10th Management Committee Meeting 2012 Venue: Bankstown Sports Club Date: 12/03/12 Attendance: Cassie, Harry, Tony, Kevin, Andrew B, Sandy, Luke, Leanne M Apologies: Peter, Ray, Rick and Leanne P Chair: Harry Meeting Opened: 7:27pm Agenda Item 10.1 Matters Arising From Previous Minutes: 8th MC: Move to adopt 1st Andrew 2nd Cassie All in favour Carried 2nd Del: LP – policy – regarding alcohol and leasing grounds. Leanne has email MC, Luke to find out if this is the most current version. Move to adopt 1st Andrew 2nd Cassie All in favour Carried Premier League: Harry forgot to minute that AA ladies 1’s falls under this as well. Move to adopt 1st Cassie 2nd Andrew All in favour Carried MC 12/03/12 Page 1 9th MC: Any reply from Padstow united. – no Goals ordered – yes Move to adopt 1st Cassie 2nd Tony All in favour Carried 10.2 Presidents Report: Thank you to the people, who did grading day, was more than expected. Cassie, Kevin, Leanne P, Andrew B and Sandy Thank you to people who attended Expo. Seems to have gone very well. Peter fro organising, Luke, Rick and Leanne M FNSW AGM – they have moved insurance into returned revenue about 7mil, 400k spent on consulatsy fee – Riverstone project review. - Andrew B and Ray mentioned for being part of disciplinary committee - We did not have to vote on the financials as they are a corporation. Grounds regarding metro- we do not have until 31/03 10.3 Secretary’s Report: Expo Report – moved to General Business Harmony Day – move to General Business 10.4 Senior Vice Report: The SSF position paper I drafted – move to General Business Web – 4500 hit this month, over 7000 in Jan over 8000 in Feb good figures. -

Auburn to Bankstown Servicing Chester Hill, Bass Hill, Georges

911 Auburn to Bankstown servicing Chester Hill, Bass Hill, Georges Hall & Yagoona How to use this timetable Fares This timetable provides a snap shot of service information in 24-hour To travel on public transport in Sydney and surrounding regions, an time (e.g. 5am = 05:00, 5pm = 17:00). Information contained in Opal card is the cheapest and easiest ticket option. this timetable is subject to change without notice. Please note that An Opal card is a smartcard you keep and reuse. You put credit onto timetables do not include minor stops, additional trips for special the card then tap on and tap off to pay your fares throughout Sydney, events, short term changes, holiday timetable changes, real-time the Blue Mountains, Central Coast, Hunter and Illawarra, along with information or any disruption alerts. Intercity Trains in the Southern Highlands and South Coast. For the most up-to-date times, use the Trip Planner or Departures on Fares are based on: transportnsw.info • the type of Opal card you use Real-time trip planning • the distance you travel from tap on to tap off You can plan your trip with real-time information using the Trip • the mode of transport you choose Planner or Departures on transportnsw.info or by downloading travel • any Opal benefits such as discounts and capped fares that apply. apps on your smartphone or tablet. Find out about Opal fares and benefits at transportnsw.info/opal The Trip Planner, Departures and travel apps offer various features: • favourite your regular trips Which Opal card is right for you? • see where your service is on the route Adult – For customers 16 years and over who are not entitled to any concessions. -

National Architecture Award Winners 1981 – 2019

NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS WINNERS 1981 - 2019 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARD WINNERS 1 of 81 2019 NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Yagan Square (WA) The COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Lyons in collaboration with Iredale Pedersen Hook and landscape architects ASPECT Studios COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURE Dangrove (NSW) The Harry Seidler Award for Commercial Architecture Tzannes Paramount House Hotel (NSW) National Award for Commercial Architecture Breathe Architecture Private Women’s Club (VIC) National Award for Commercial Architecture Kerstin Thompson Architects EDUCATIONAL ARCHITECTURE Our Lady of the Assumption Catholic Primary School (NSW) The Daryl Jackson Award for Educational Architecture BVN Braemar College Stage 1, Middle School National Award for Educational Architecture Hayball Adelaide Botanic High School (SA) National Commendation for Educational Architecture Cox Architecture and DesignInc QUT Creative Industries Precinct 2 (QLD) National Commendation for Educational Architecture KIRK and HASSELL (Architects in Association) ENDURING ARCHITECTURE Sails in the Desert (NT) National Award for Enduring Architecture Cox Architecture HERITAGE Premier Mill Hotel (WA) The Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage Spaceagency architects Paramount House Hotel (NSW) National Award for Heritage Breathe Architecture Flinders Street Station Façade Strengthening & Conservation National Commendation for Heritage (VIC) Lovell Chen Sacred Heart Building Abbotsford Convent Foundation -

Dates Worth Noting

CCAREER MAILBOX Thursday 5th May 2016 DATES WORTH NOTING News from the University of Melbourne Engineering & I T Programs for School Students The University of Melbourne offers a range of exciting opportunities for secondary school students to visit Parkville campus and experience Engineering & IT. Some of these programs include – Hands on Computing Find out what computing and information systems study involves and the careers that can follow, through this interactive day long program. No particular computer skills are required except for an inquisitive and creative mind! Students will also have the opportunity to meet with academics and current students. Date: Tuesday 28 June 2016 Time: 9.00am – 3.30pm Hands on Engineering Hands on Engineering is a day-long program, for Year 10 students who are interested in mathematics and science, providing hands on experience in a variety of fun activities and workshops to learn about the different fields of engineering. Students will also have the opportunity to tour the campus and meet with academics and current students. Date: Thursday 30 June 2016 Time: 9.00am – 3.30pm To find out more about either of the above mentioned, and/or to register, visit Engineering & I T Holiday Programs VCA Schools Program – Walks of Art 2016 Aimed at Visual Art students and their teachers, this walking tour will take you around alleyways and into some of the smaller artist-run gallery spaces around Melbourne. Learn more about the contemporary visual art scene in Melbourne, and be inspired! This series of walking tours will be hosted by a VCA final year visual art student. -

Structures Readings Book

Structures in tertiary education and training: a kaleidoscope or merely fragments? Research readings NATIONAL CENTRE FOR VOCATIONAL EDUCATION RESEARCH Edited by Francesca Beddie Laura O’Connor Penelope Curtin Structures in tertiary education and training: a kaleidoscope or merely fragments? Research readings Edited by Francesca Beddie Laura O’Connor Penelope Curtin NATIONAL VOCATIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING RESEARCH PROGRAM RESEARCH READINGS The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author/ project team and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government or state and territory governments. Any interpretation of data is the responsibility of the author/project team. © Commonwealth of Australia, 2013 With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, the Department’s logo, any material protected by a trade mark and where otherwise noted all material presented in this document is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia <creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au> licence. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website (accessible using the links provided) as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence <creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/legalcode>. The Creative Commons licence conditions do not apply to all logos, graphic design, artwork and photographs. Requests and enquiries concerning other reproduction and rights should be directed to the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER). This document should be attributed as Beddie, F, O’Connor, L & Curtin, P (eds) 2013, Structures in tertiary education and training: a kaleidoscope or merely fragments? Research readings, NCVER, Adelaide. -

Department of Education & Training 2016-2020 Strategic

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION & TRAINING 2016 -2020 STRATEGIC PLAN CONTENTS SECRETARY’S MESSAGE .......................................................................................................................................... 3 STRATEGIC INTENT .................................................................................................................................................... 4 OUR VISION .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 OUR OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................................................... 4 OUR VALUES ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 OUR OUTCOMES...................................................................................................................................................... 5 DET OUTCOMES FRAMEWORK .............................................................................................................................. 5 EDUCATION STATE TARGETS ................................................................................................................................ 5 DET OUTCOME INDICATORS .................................................................................................................................. 8 CONTEXT: CHALLENGES AND RISKS -

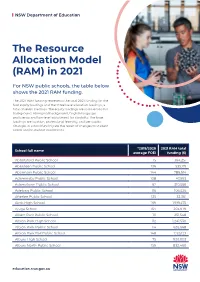

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 347,551 Alma Public -

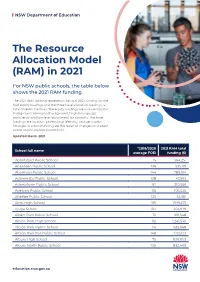

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Religion, Cultural Diversity and Safeguarding Australia

Cultural DiversityReligion, and Safeguarding Australia A Partnership under the Australian Government’s Living In Harmony initiative by Desmond Cahill, Gary Bouma, Hass Dellal and Michael Leahy DEPARTMENT OF IMMIGRATION AND MULTICULTURAL AND INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS and AUSTRALIAN MULTICULTURAL FOUNDATION in association with the WORLD CONFERENCE OF RELIGIONS FOR PEACE, RMIT UNIVERSITY and MONASH UNIVERSITY (c) Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2004 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth available from the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Intellectual Property Branch, Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts, GPO Box 2154, Canberra ACT 2601 or at http:www.dcita.gov.au The statement and views expressed in the personal profiles in this book are those of the profiled person and are not necessarily those of the Commonwealth, its employees officers and agents. Design and layout Done...ByFriday Printed by National Capital Printing ISBN: 0-9756064-0-9 Religion,Cultural Diversity andSafeguarding Australia 3 contents Chapter One Introduction . .6 Religion in a Globalising World . .6 Religion and Social Capital . .9 Aim and Objectives of the Project . 11 Project Strategy . 13 Chapter Two Historical Perspectives: Till World War II . 21 The Beginnings of Aboriginal Spirituality . 21 Initial Muslim Contact . 22 The Australian Foundations of Christianity . 23 The Catholic Church and Australian Fermentation . 26 The Nonconformist Presence in Australia . 28 The Lutherans in Australia . 30 The Orthodox Churches in Australia . -

The Married Woman, the Teaching Profession and the State in Victoria, 1872-1956

THE MARRIED WOMAN, THE TEACHING PROFESSION AND THE STATE IN VICTORIA, 1872-1956 Donna Dwyer B.A., Dip. Ed. (Monash), Dip. Crim., M.Ed. (Melb.) Submitted in fulfilmentof the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Educafion at The University of Melbourne 2002 , . Abstract This thesis is a study of married women's teaching labour in the Victorian Education Department. It looks at the rise to power of married women teachers, the teaching matriarchs. in the 1850s and 1860s in early colonial Victoria when married women teachers were valued for the moral propriety their presence brought to the teaching of female pupils. In 1872 the newly created Victorian Education Department would herald a new regime and the findings of the Rogers Templeton Commission spell doom for married women teachers. The thesis traces their expulsion from the service under the 1889 Public Service Act implementing the marriage bar. The labyrinthine legislation that followed the passing of the Public Service Act 1889 defies adequate explanation but the outcome was clear. For the next sixty-seven years the bar would remain in place, condemning the 'needy' married woman teacher to life as an itinerant temporary teacher at the mercy of the Department. The irony was that this sometimes took place under 'liberal' administrators renowned for their reformist policies. When married women teachers returned in considerable numbers during the Second World War, they were supported in their claim for reinstatement by women unionists in the Victorian Teachers' Union (VTU). In the 1950s married women temporary teachers, members of the VTU, took up the fight, forming the Temporary Teachers' Club (TIC) to press home their claims.