American Empire, Filipino American Postcoloniality, and the US

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States of America Assassination

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ASSASSINATION RECORDS REVIEW BOARD *** PUBLIC HEARING Federal Building 1100 Commerce Room 7A23 Dallas, Texas Friday, November 18, 1994 The above-entitled proceedings commenced, pursuant to notice, at 10:00 a.m., John R. Tunheim, chairman, presiding. PRESENT FOR ASSASSINATION RECORDS REVIEW BOARD: JOHN R. TUNHEIM, Chairman HENRY F. GRAFF, Member KERMIT L. HALL, Member WILLIAM L. JOYCE, Member ANNA K. NELSON, Member DAVID G. MARWELL, Executive Director WITNESSES: JIM MARRS DAVID J. MURRAH ADELE E.U. EDISEN GARY MACK ROBERT VERNON THOMAS WILSON WALLACE MILAM BEVERLY OLIVER MASSEGEE STEVE OSBORN PHILIP TenBRINK JOHN McLAUGHLIN GARY L. AGUILAR HAL VERB THOMAS MEROS LAWRENCE SUTHERLAND JOSEPH BACKES MARTIN SHACKELFORD ROY SCHAEFFER 2 KENNETH SMITH 3 P R O C E E D I N G S [10:05 a.m.] CHAIRMAN TUNHEIM: Good morning everyone, and welcome everyone to this public hearing held today in Dallas by the Assassination Records Review Board. The Review Board is an independent Federal agency that was established by Congress for a very important purpose, to identify and secure all the materials and documentation regarding the assassination of President John Kennedy and its aftermath. The purpose is to provide to the American public a complete record of this national tragedy, a record that is fully accessible to anyone who wishes to go see it. The members of the Review Board, which is a part-time citizen panel, were nominated by President Clinton and confirmed by the United States Senate. I am John Tunheim, Chair of the Board, I am also the Chief Deputy Attorney General from Minnesota. -

Marcela M. Agoncillo

National Historical Commission of the Philippines MARCELA M. AGONCILLO MARCELA M. AGONCILLO (1860-1946)Maker of the Filipino National Flag Enshrined in Philippine history as the maker of the Filipino flag, Marcela Mariño Agoncillo was born in Taal, Batangas on 24 June 1859 to Francisco Mariño and Eugenia Coronel. Marcela was reputed to be the prettiest in Batangas so she was fondly called “Roselang Bubog” and like any daughter of a rich couple, a maid or an elderly relative always accompanied her. She was sent to study at the Sta. Catalina College run by the Dominican nuns in Intramuros, Manila. It was in this school that she was trained well. She learned Spanish, music, crafts, and social graces expected from a Filipina of social stature. A noted singer and one who occasionally appeared in zarzuelas in Batangas, Marcela attracted many suitors but it was the rich young lawyer, Don Felipe Agoncillo, who won her heart. The two got married and had six daughters: Lorenza, Gregoria, Eugenia, Marcela, Adela (who died at the age of 3), and Maria. Their daughters were trained to be respectable women, always reminding them to live honestly and well and to work hard without depending on the family wealth. One with a heart for her nation, she stood by her husband in defending their poor town mates against the corrupt Spanish authorities. Felipe was branded filibustero but this did not deter her loyalty to him. Instead, she calmly accepted her husband’s decision to go into self-exile in Hong Kong. She and her children later followed in Hongkong. -

Nationalism, Citizenship and the Politics of Filipino Migrant Labor ROBYN M

Citizenship Studies, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2002 Migrant Heroes: Nationalism, Citizenship and the Politics of Filipino Migrant Labor ROBYN M. RODRIGUEZ The Philippine state has popularized the idea of Filipino migrants as the country’s ‘new national heroes’, critically transforming notions of Filipino citizenship and citizenship struggles. As ‘new national heroes’, migrant workers are extended particular kinds of economic and welfare rights while they are abroad even as they are obligated to perform particular kinds of duties to their home state. The author suggests that this transnationalize d citizenship, and the obligations attached to it, becomes a mode by which the Philippine state ultimately disciplines Filipino migrant labor as exible labor. However, as citizenship is extended to Filipinos beyond the borders of the Philippines, the globalizatio n of citizenship rights has enabled migrants to make various kinds of claims on the Philippine state. Indeed, these new transnationa l political strug- gles have given rise not only to migrants’ demands for rights, but to alternative nationalisms and novel notions of citizenship that challenge the Philippine state’s role in the export and commodi cation of migrant workers. Introduction In 1995, Flor Contemplacion, a Singapore-based Filipina domestic worker, was hanged by the Singaporean government for allegedly killing another Filipina domestic worker and the child in her charge. When news about her imminent death reached the Philippines, Filipinos, throughout the nation and around the globe, went to the streets demanding that the Philippine government intervene to prevent Contemplacion’s execution. Fearing Philippine– Singapore diplomatic relations would be threatened, then-Philippine President Fidel Ramos was reluctant to intercede despite evidence that may have proved her innocence. -

ANTH 317 Final Paper

Castilian Friars, Colonialism and Language Planning: How the Philippines Acquired a Non- Spanish National Language The topic of the process behind the establishment of a national language, who chooses it, when and why, came to me in an unexpected way. The UBC Philippine Studies Series hosted an art exhibit in Fall 2011 that was entitled MAHAL. This exhibit consisted of artworks by Filipino/a students that related to the Filipino migratory experience(s). I was particularly fascinated by the piece entitled Ancients by Chaya Go (Fig 1). This piece consisted of an image, a map of the Philippines, superimposed with Aztec and Mayan imprints and a pre-colonial Filipina priestess. Below it was a poem, written in Spanish. Chaya explained that “by writing about an imagined ‘home’ (the Philippines) in a language that is not ours anymore, I am playing with the idea of who is Filipino and who belongs to the country” (personal communication, November 29 2011). What I learned from Chaya Go and Edsel Ya Chua that evening at MAHAL, that was confirmed in the research I uncovered, was that in spite of being colonized for over three hundred and fifty years the Philippines now has a national language, Filipino, that is based on the Tagalog language which originated in and around Manila, the capital city of the Philippines (Himmelmann 2005:350). What fascinated me was that every Spanish colony that I could think of, particularly in Latin and South America, adopted Spanish as their national language even after they gained independence from Spain. This Spanish certainly differed from the Spanish in neighboring countries and regions, as each form of Spanish was locally influenced by the traditional languages that had existed before colonization, but its root was Spanish and it identified itself as Spanish. -

Necessary Fictions”: Authorship and Transethnic Identity in Contemporary American Narratives

MILNE, LEAH A., PhD. “Necessary Fictions”: Authorship and Transethnic Identity in Contemporary American Narratives. (2015) Directed by Dr. Christian Moraru. 352 pp. As a theory and political movement of the late 20th century, multiculturalism has emphasized recognition, tolerance, and the peaceful coexistence of cultures, while providing the groundwork for social justice and the expansion of the American literary canon. However, its sometimes uncomplicated celebrations of diversity and its focus on static, discrete ethnic identities have been seen by many as restrictive. As my project argues, contemporary ethnic American novelists are pushing against these restrictions by promoting what I call transethnicity, the process by which one formulates a dynamic conception of ethnicity that cuts across different categories of identity. Through the use of self-conscious or metafictional narratives, authors such as Louise Erdrich, Junot Díaz, and Percival Everett mobilize metafiction to expand definitions of ethnicity and to acknowledge those who have been left out of the multicultural picture. I further argue that, while metafiction is often considered the realm of white male novelists, ethnic American authors have galvanized self-conscious fiction—particularly stories depicting characters in the act of writing—to defy multiculturalism’s embrace of coherent, reducible ethnic groups who are best represented by their most exceptional members and by writing that is itself correct and “authentic.” Instead, under the transethnic model, ethnicity is self-conflicted, forged through ongoing revision and contestation and in ever- fluid responses to political, economic, and social changes. “NECESSARY FICTIONS”: AUTHORSHIP AND TRANSETHNIC IDENTITY IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN NARRATIVES by Leah A. Milne A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Greensboro 2015 Approved by _____________________ Committee Chair ©2015 Leah A. -

1 Colophon: the Friends of the SMU Libraries: the First Twenty Years By

1 Colophon: The Friends of the SMU Libraries: The First Twenty Years By Michael V. Hazel In the fall of 1970 Southern Methodist University celebrated its fifty-fifth anniversary. From a small college on a weed- choked prairie several miles north of downtown Dallas, it had developed into one of the major centers of learning in the state of Texas, with an outstanding faculty and a student body numbering close to 10,000. The university's growth had been paralleled--had, in fact, been made possible--by the development of its libraries. The Bridwell Library, serving Perkins School of Theology, had recently added a wing, and under the leadership of Librarian Decherd Turner had begun acquiring the rare volumes and early examples of fine printing which would bring its collections national renown. A new four-story wing had just been added to Fondren Library, greatly expanding shelf space for the central library, as well as creating new reference and reading areas. The Underwood Law Library opened its doors that fall of 1970, providing law students for the first time with a spacious, modern facility. 2 With the libraries' physical plant so greatly improved, attention turned to the collections themselves. Through the fiscal inflation of the late 1960s, the cost of books and periodicals had escalated, and it was clear that the university's budget could not meet all the libraries' needs. The libraries needed friends. And because SMU represented such an important cultural and educational resource to the Dallas community, it seemed only logical to look to that community for support. -

Table of Contents

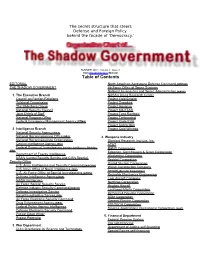

The secret structure that steers Defense and Foreign Policy behind the facade of 'Democracy.' SUMMER 2001 - Volume 1, Issue 3 from TrueDemocracy Website Table of Contents EDITORIAL North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) THE SHADOW GOVERNMENT Air Force Office of Space Systems National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 1. The Executive Branch NASA's Ames Research Center Council on Foreign Relations Project Cold Empire Trilateral Commission Project Snowbird The Bilderberg Group Project Aquarius National Security Council Project MILSTAR Joint Chiefs of Staff Project Tacit Rainbow National Program Office Project Timberwind Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Project Code EVA Project Cobra Mist 2. Intelligence Branch Project Cold Witness National Security Agency (NSA) National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) 4. Weapons Industry National Reconnaissance Organization Stanford Research Institute, Inc. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) AT&T Federal Bureau of Investigation , Counter Intelligence Division RAND Corporation (FBI) Edgerton, Germhausen & Greer Corporation Department of Energy Intelligence Wackenhut Corporation NSA's Central Security Service and CIA's Special Bechtel Corporation Security Office United Nuclear Corporation U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Walsh Construction Company U.S. Navy Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) Aerojet (Genstar Corporation) U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) Reynolds Electronics Engineering Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lear Aircraft Company NASA Intelligence Northrop Corporation Air Force Special Security Service Hughes Aircraft Defense Industry Security Command (DISCO) Lockheed-Maritn Corporation Defense Investigative Service McDonnell-Douglas Corporation Naval Investigative Service (NIS) BDM Corporation Air Force Electronic Security Command General Electric Corporation Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) PSI-TECH Corporation Federal Police Agency Intelligence Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) Defense Electronic Security Command Project Deep Water 5. -

2016 International Congress on Action Research

3Repub!ic of tbe ~bilippines 11Bepartment of Ql;bucation Region XI SCHOOLS DIVISION OF DIGOS CITY Digos City DIVISTON MEMORANDUM December 10, 2015 No.9bg. , s. 2015 CALL FOR PARTICIPANTS TO THE ACTION RESEARCH, ACTION LEARNING (ARAL) 2016 CONGRESS To: Education Program Supervisors Public Schools District Supervisors School Heads of Private and Public Schools Teachers of Private and Public Schools All Others Concerned 1. In compliance with DepED Advisory No . 345, s . 2015, this Office is issuing this memorandum to call for participants to the Action Research, Action Learning (ARAL) 2016 Congress at De La Salle University- Manila from March 3-5, 2016. 2. The aim of this international action research congress is to provide participants with deeper appreciation of the need and importance of action research, equip researchers with different methodologies in conducting action research, and provide a venue for discussing possible collaboration among other action researchers. 3. Participation of both public and private schools shall be subject to the no- disruption-of-classes policy stipulated in DepED Order No. 9 , s. 2005. 4. Participants coming from public schools shall join this event on official time. 5. Participants shall pre-register online at www.aralcongress.weebly.com. 6. Details of this event are available in the enclosures of this memorandum. 7. Immediate and wide dissemination of this memorandum is desired. ~ DEE D. SILVA, DPA, CESO VI r Assistant Schools-Division Superintendent Officer In-Charge Ends: Invitation letter from LIDER DepED Advisory No. 345, s. 2015 ARAL 2016 Flyer ARAL 2016 Tentative Schedule References: DepED Advisory No. 345, s . 2015 DepED Order No. -

Diaspora Philanthropy: the Philippine Experience

Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience ______________________________________________________________________ Victoria P. Garchitorena President The Ayala Foundation, Inc. May 2007 _________________________________________ Prepared for The Philanthropic Initiative, Inc. and The Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University Supported by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation ____________________________________________ Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience I . The Philippine Diaspora Major Waves of Migration The Philippines is a country with a long and vibrant history of emigration. In 2006 the country celebrated the centennial of the first surge of Filipinos to the United States in the very early 20th Century. Since then, there have been three somewhat distinct waves of migration. The first wave began when sugar workers from the Ilocos Region in Northern Philippines went to work for the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association in 1906 and continued through 1929. Even today, an overwhelming majority of the Filipinos in Hawaii are from the Ilocos Region. After a union strike in 1924, many Filipinos were banned in Hawaii and migrant labor shifted to the U.S. mainland (Vera Cruz 1994). Thousands of Filipino farm workers sailed to California and other states. Between 1906 and 1930 there were 120,000 Filipinos working in the United States. The Filipinos were at a great advantage because, as residents of an American colony, they were regarded as U.S. nationals. However, with the passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934, which officially proclaimed Philippine independence from U.S. rule, all Filipinos in the United States were reclassified as aliens. The Great Depression of 1929 slowed Filipino migration to the United States, and Filipinos sought jobs in other parts of the world. -

Death by Garrote Waiting in Line at the Security Checkpoint Before Entering

Death by Garrote Waiting in line at the security checkpoint before entering Malacañang, I joined Metrobank Foundation director Chito Sobrepeña and Retired Justice Rodolfo Palattao of the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan who were discussing how to inspire the faculty of the Unibersidad de Manila (formerly City College of Manila) to become outstanding teachers. Ascending the grand staircase leading to the ceremonial hall, I told Justice Palattao that Manuel Quezon never signed a death sentence sent him by the courts because of a story associated with these historic steps. Quezon heard that in December 1896 Jose Rizal's mother climbed these steps on her knees to see the governor-general and plead for her son's life. Teodora Alonso's appeal was ignored and Rizal was executed in Bagumbayan. At the top of the stairs, Justice Palattao said "Kinilabutan naman ako sa kinuwento mo (I had goosebumps listening to your story)." Thus overwhelmed, he missed Juan Luna's Pacto de Sangre, so I asked "Ilan po ang binitay ninyo? (How many people did you sentence to death?)" "Tatlo lang (Only three)", he replied. At that point we were reminded of retired Sandiganbayan Justice Manuel Pamaran who had the fearful reputation as The Hanging Judge. All these morbid thoughts on a cheerful morning came from the morbid historical relics I have been contemplating recently: a piece of black cloth cut from the coat of Rizal wore to his execution, a chipped piece of Rizal's backbone displayed in Fort Santiago that shows where the fatal bullet hit him, a photograph of Ninoy Aquino's bloodstained shirt taken in 1983, the noose used to hand General Yamashita recently found in the bodega of the National Museum. -

In 1983, the Late Fred Cordova

Larry Dulay Itliong was born in the Pangasinan province of the Philippines on October 25th, 1913. As a young teen, he immigrated to the US in search of work. Itliong soon joined laborers In 1983, the late Fred Cordova (of the Filipino American National Historical Society) wrote a working everywhere from Washington to California to Alaska, organizing unions and labor strikes book called Filipinos: Forgotten Asian Americans, a pictorial essay documenting the history of as he went. He was one of the manongs, Filipino bachelors in laborer jobs who followed the Filipinos in America from 1763 to 1963. He used the word “forgotten” to highlight that harvest. Filipino Americans were invisible in American history books during that time. Despite lacking a formal secondary education, Itliong spoke multiple languages and taught himself about law by attending trials. In 1965, he led a thousand Filipino farm workers to strike Though Filipino Americans were the first Asian Americans to arrive in the U.S. in 1587 (33 against unfair labor practices in Delano, CA. His leadership in Filipino farm worker movement years before the Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock in 1620), little was written about the history paved the way for others to follow. Alongside Cesar Chavez, Larry Itliong founded the United of the Philippines or of Filipino Americans in the U.S. Although the U.S. has a long history with Farm Workers Union. Together, they built an unprecedented coalition between Filipino and the Philippines (including the Philippine-American War, American colonization from 1899-1946, Mexican laborers and connected their strike to the concurrent Civil Rights Movement. -

The Development of the Philippine Foreign Service

The Development of the Philippine Foreign Service During the Revolutionary Period and the Filipino- American War (1896-1906): A Story of Struggle from the Formation of Diplomatic Contacts to the Philippine Republic Augusto V. de Viana University of Santo Tomas The Philippine foreign service traces its origin to the Katipunan in the early 1890s. Revolutionary leaders knew that the establishment of foreign contacts would be vital to the success of the objectives of the organization as it struggles toward the attainment of independence. This was proven when the Katipunan leaders tried to secure the support of Japanese and German governments for a projected revolution against Spain. Some patriotic Filipinos in Hong Kong composed of exiles also supported the Philippine Revolution.The organization of these exiled Filipinos eventually formed the nucleus of the Philippine Central Committee, which later became known as the Hong Kong Junta after General Emilio Aguinaldo arrived there in December 1897. After Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines in May 1898, he issued a decree reorganizing his government and creating four departments, one of which was the Department of Foreign Relations, Navy, and Commerce. This formed the basis of the foundation of the present Department of Foreign Affairs. Among the roles of this office was to seek recognition from foreign countries, acquire weapons and any other needs of the Philippine government, and continue lobbying for support from other countries. It likewise assigned emissaries equivalent to today’s ambassadors and monitored foreign reactions to the developments in the Philippines. The early diplomats, such as Felipe Agoncillo who was appointed as Minister Plenipotentiary of the revolutionary government, had their share of hardships as they had to make do with meager means.