Fasting Compared with Nonfasting Triglycerides and Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blood Fats Explained

Blood Fats Explained HEART UK – The Cholesterol Charity providing expert support, education and influence 2 | Fats in the blood At risk of cardiovascular disease? | 3 Fats in the blood At risk of cardiovascular disease? Fats that circulate in the blood are called lipids. Very low density lipoproteins (VLDL) transport Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the medical Blood pressure is a measure of the resistance Cholesterol and triglycerides are both lipids. mainly triglycerides made by the liver to where name for circulatory diseases such as coronary to the flow of blood around your body. It is They have essential roles in the body. In excess they are either used to fuel our muscles or stored heart disease (CHD), stroke, mini stroke (transient measured in millimetres of mercury (mmHg). Your they are harmful. for later use. ischaemic attack or TIA), angina and peripheral doctor or nurse will measure both your systolic vascular disease (PVD). You are more likely to (upper figure) and diastolic (lower figure) blood Cholesterol is needed to build cell walls and Low density lipoproteins (LDL) carry most of the develop CVD the more risk factors you have. pressure. About a third of adults have high blood to make hormones and vitamin D. Some of our cholesterol in our body from the liver to the cells pressure. If untreated it increases the risk of cholesterol comes from the food we eat; but most that need it. The cholesterol that is carried on LDLs There are two types of risk factors: heart attack and stroke. High blood pressure is is made in the liver. -

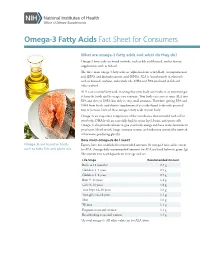

Omega-3 Fatty Acids Fact Sheet for Consumers

Omega-3 Fatty Acids Fact Sheet for Consumers What are omega-3 fatty acids and what do they do? Omega-3 fatty acids are found in foods, such as fish and flaxseed, and in dietary supplements, such as fish oil. The three main omega-3 fatty acids are alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). ALA is found mainly in plant oils such as flaxseed, soybean, and canola oils. DHA and EPA are found in fish and other seafood. ALA is an essential fatty acid, meaning that your body can’t make it, so you must get it from the foods and beverages you consume. Your body can convert some ALA into EPA and then to DHA, but only in very small amounts. Therefore, getting EPA and DHA from foods (and dietary supplements if you take them) is the only practical way to increase levels of these omega-3 fatty acids in your body. Omega-3s are important components of the membranes that surround each cell in your body. DHA levels are especially high in retina (eye), brain, and sperm cells. Omega-3s also provide calories to give your body energy and have many functions in your heart, blood vessels, lungs, immune system, and endocrine system (the network of hormone-producing glands). How much omega-3s do I need? Omega-3s are found in foods Experts have not established recommended amounts for omega-3 fatty acids, except such as fatty fish and plant oils. for ALA. Average daily recommended amounts for ALA are listed below in grams (g). -

Omega-6:Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio and Total Fat Content of the Maternal Diet Alter Offspring Growth and Fat Deposition in the Rat

nutrients Article Omega-6:Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio and Total Fat Content of the Maternal Diet Alter Offspring Growth and Fat Deposition in the Rat Sally A. V. Draycott 1,2,*, Matthew J. Elmes 1, Beverly S. Muhlhausler 2,3 and Simon Langley-Evans 1 1 Sutton Bonington Campus, School of Biosciences, University of Nottingham, Loughborough LE12 5RD, UK; [email protected] (M.J.E.); [email protected] (S.L.-E.) 2 Food and Nutrition Research Group, Department of Food and Wine Science, School of Agriculture, Food and Wine, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5064, Australia; [email protected] 3 Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 July 2020; Accepted: 13 August 2020; Published: 19 August 2020 Abstract: Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA) have been shown to inhibit lipogenesis and adipogenesis in adult rats. Their possible early life effects on offspring fat deposition, however, remain to be established. To investigate this, female Wistar rats (n = 6–9 per group) were fed either a 9:1 ratio of linoleic acid (LA) to alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) or a lower 1:1.5 ratio during pregnancy and lactation. Each ratio was fed at two total fat levels (18% vs. 36% fat w/w) and offspring were weaned onto standard laboratory chow. Offspring exposed to a 36% fat diet, irrespective of maternal dietary LA:ALA ratio, were lighter (male, 27 g lighter; female 19 g lighter; p < 0.0001) than those exposed to an 18% fat diet between 3 and 8 weeks of age. -

Omega-3, Omega-6 and Omega-9 Fatty Acids

Johnson and Bradford, J Glycomics Lipidomics 2014, 4:4 DOI: 0.4172/2153-0637.1000123 Journal of Glycomics & Lipidomics Review Article Open Access Omega-3, Omega-6 and Omega-9 Fatty Acids: Implications for Cardiovascular and Other Diseases Melissa Johnson1* and Chastity Bradford2 1College of Agriculture, Environment and Nutrition Sciences, Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, Alabama, USA 2Department of Biology, Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, Alabama, USA Abstract The relationship between diet and disease has long been established, with epidemiological and clinical evidence affirming the role of certain dietary fatty acid classes in disease pathogenesis. Within the same class, different fatty acids may exhibit beneficial or deleterious effects, with implications on disease progression or prevention. In conjunction with other fatty acids and lipids, the omega-3, -6 and -9 fatty acids make up the lipidome, and with the conversion and storage of excess carbohydrates into fats, transcendence of the glycome into the lipidome occurs. The essential omega-3 fatty acids are typically associated with initiating anti-inflammatory responses, while omega-6 fatty acids are associated with pro-inflammatory responses. Non-essential, omega-9 fatty acids serve as necessary components for other metabolic pathways, which may affect disease risk. These fatty acids which act as independent, yet synergistic lipid moieties that interact with other biomolecules within the cellular ecosystem epitomize the critical role of these fatty acids in homeostasis and overall health. This review focuses on the functional roles and potential mechanisms of omega-3, omega-6 and omega-9 fatty acids in regard to inflammation and disease pathogenesis. A particular emphasis is placed on cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. -

2015 National Lipid Association

Journal of Clinical Lipidology (2015) -, -–- Original Contribution National Lipid Association Recommendations for Patient-Centered Management of Dyslipidemia: Part 1—Full Report Terry A. Jacobson, MD*, Matthew K. Ito, PharmD, Kevin C. Maki, PhD, Carl E. Orringer, MD, Harold E. Bays, MD, Peter H. Jones, MD, James M. McKenney, PharmD, Scott M. Grundy, MD, PhD, Edward A. Gill, MD, Robert A. Wild, MD, PhD, Don P. Wilson, MD, W. Virgil Brown, MD Department of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA (Dr Jacobson); Oregon State University/Oregon Health & Science University, College of Pharmacy, Portland, OR, USA (Dr Ito); Midwest Center for Metabolic & Cardiovascular Research and DePaul University, Chicago, IL, USA (Dr Maki); University of Miami Health System, Miami, FL, USA (Dr Orringer); Louisville Metabolic and Atherosclerosis Research Center, Louisville, KY, USA (Dr Bays); Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA (Dr Jones); Virginia Commonwealth University and National Clinical Research, Richmond, VA, USA (Dr McKenney); The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA (Dr Grundy); University of Washington/Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA (Dr Gill); Oklahoma University Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA (Dr Wild); Cook Children’s Medical Center, Fort Worth, TX, USA (Dr Wilson); and Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA (Dr Brown) KEYWORDS: Abstract: The leadership of the National Lipid Association convened an Expert Panel to develop a Clinical consensus set of recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia in clinical med- recommendations; icine. An Executive Summary of those recommendations was previously published. This document Dyslipidemia; provides support for the recommendations outlined in the Executive Summary. -

Insulin Regulates Hepatic Triglyceride Secretion and Lipid Content Via Signaling in the Brain

Diabetes Page 2 of 37 Insulin regulates hepatic triglyceride secretion and lipid content via signaling in the brain Short Title: Brain insulin regulates hepatic VLDL secretion Thomas Scherer1,2,5, Claudia Lindtner1, James O’Hare1, Martina Hackl2, Elizabeth Zielinski1, Angelika Freudenthaler2, Sabina Baumgartner-Parzer2, Klaus Tödter3, Joerg Heeren3, Martin Krššák2,4, Ludger Scheja3, Clemens Fürnsinn2 & Christoph Buettner1,5 1Department of Medicine and Department of Neuroscience, Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, One Gustave L. Levy Place, New York, NY 10029, USA 2Department of Medicine III, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, 1090 Vienna, Austria 3Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Cell Biology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, 20246 Hamburg, Germany 4High Field MR Centre, Department of Biomedical Imaging and Image Guided Therapy, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, 1090 Vienna, Austria 5To whom correspondence should be addressed. E–mail: [email protected] or [email protected] T.S.: Phone: +43 1 40400 47850; Fax: +43 1 40400 77900 C.B.: Phone: +1 212 241 3425; Fax: +1 212 241 4218 Key words: brain; insulin; triglyceride secretion; hepatic lipid content Word count: 3998 Figures: 4 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online February 9, 2016 Page 3 of 37 Diabetes Non-standard abbreviations ARC: arcuate nucleus; CNS: central nervous system; CSF: cerebrospinal -

Omega-3 Versus Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory Skin Diseases

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Omega-3 Versus Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory Skin Diseases Anamaria Bali´c 1 , Domagoj Vlaši´c 2, Kristina Žužul 3, Branka Marinovi´c 1 and Zrinka Bukvi´cMokos 1,* 1 Department of Dermatology and Venereology, University Hospital Centre Zagreb, School of Medicine University of Zagreb, Šalata 4, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (B.M.) 2 Department of Ophtalmology and Optometry, General Hospital Dubrovnik, Ulica dr. Roka Mišeti´ca2, 20000 Dubrovnik, Croatia; [email protected] 3 School of Medicine, University of Zagreb, Šalata 3, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 31 December 2019; Accepted: 21 January 2020; Published: 23 January 2020 Abstract: Omega-3 (!-3) and omega-6 (!-6) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are nowadays desirable components of oils with special dietary and functional properties. Their therapeutic and health-promoting effects have already been established in various chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases through various mechanisms, including modifications in cell membrane lipid composition, gene expression, cellular metabolism, and signal transduction. The application of !-3 and !-6 PUFAs in most common skin diseases has been examined in numerous studies, but their results and conclusions were mostly opposing and inconclusive. It seems that combined !-6, gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), and -

Parenteral Nutrition and Lipids

nutrients Review Parenteral Nutrition and Lipids Maitreyi Raman 1,*, Abdulelah Almutairdi 1, Leanne Mulesa 2, Cathy Alberda 2, Colleen Beattie 2 and Leah Gramlich 3 1 Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary, G055 3330 Hospital Drive, Calgary, AB T2N 4N1, Canada; [email protected] 2 Alberta Health Services, Seventh Street Plaza, 14th Floor, North Tower, 10030–107 Street NW, Edmonton, AB T5J 3E4, Canada; [email protected] (L.M.); [email protected] (C.A.); [email protected] (C.B.) 3 Division of Gastroenterology, Royal Alexandra Hospital, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T5H 3V9, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-403-592-5020 Received: 4 March 2017; Accepted: 10 April 2017; Published: 14 April 2017 Abstract: Lipids have multiple physiological roles that are biologically vital. Soybean oil lipid emulsions have been the mainstay of parenteral nutrition lipid formulations for decades in North America. Utilizing intravenous lipid emulsions in parenteral nutrition has minimized the dependence on dextrose as a major source of nonprotein calories and prevents the clinical consequences of essential fatty acid deficiency. Emerging literature has indicated that there are benefits to utilizing alternative lipids such as olive/soy-based formulations, and combination lipids such as soy/MCT/olive/fish oil, compared with soybean based lipids, as they have less inflammatory properties, are immune modulating, have higher antioxidant content, decrease risk of cholestasis, and improve clinical outcomes in certain subgroups of patients. The objective of this article is to review the history of IVLE, their composition, the different generations of widely available IVLE, the variables to consider when selecting lipids, and the complications of IVLE and how to minimize them. -

Triglycerides

TRIGLYCERIDES OSR60118 4 x 20 mL R1 4 x 5 mL R2 OSR61118 4 x 50 mL R1 4 x 12.5 mL R2 *OSR66118 4 x 167 mL R1 4 x 43 mL R2 Intended Use System reagent for the quantitative determination of Triglyceride concentrations in human serum and plasma on Beckman Coulter AU analyzers. *Triglycerides reagent OSR66118 for use on the AU2700/5400 system only. Summary Triglycerides are the major form of fat found in nature and their primary function is to provide energy for the cell.1 Measurements of triglyceride are used in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with diabetes mellitus, nephrosis, liver obstruction, other diseases involving lipid metabolism, or various endocrine disorders.2 Clinically, triglyceride assays are used to help classify the various genetic and metabolic lipoprotein disorders and in the assessment of risk factors for atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease.3,4 Methodology This Triglyceride procedure is based on a series of coupled enzymatic reactions.5,6 The triglycerides in the sample are hydrolyzed by a combination of microbial lipases to give glycerol and fatty acids. The glycerol is phosphorylated by adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in the presence of glycerol kinase (GK) to produce glycerol-3-phosphate. The glycerol-3-phosphate is oxidized by molecular oxygen in the presence of GPO (glycerol phosphate oxidase) to produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and dihydroxyacetone phosphate. The formed H2O2 reacts with 4-aminophenazone and N,N-bis(4-sulfobutyl)-3,5-dimethylaniline, disodium salt (MADB) in the presence of peroxidase (POD) to produce a chromophore, which is read at 660/800nm. -

Experiment 12 –Lipids Structures of Common Fatty Acids

Experiment 12 –Lipids Lipids are a class of biological molecules that are insoluble in water and soluble in nonpolar solvents. There are many different categories of lipids and each category has different components present in its structure. Fatty acids are components of many types of lipids. Fatty acids are carboxylic acids with very long hydrocarbon chains, usually 12-18 carbon atoms long. Even though these carboxylic acids can hydrogen bond with water, they are insoluble because of the length of their hydrocarbon chains. Fatty acids can be saturated or unsaturated. A saturated fatty acid contains no carbon-carbon double bonds, so it is “saturated” with hydrogen. Unsaturated fatty acids contain one or more cis double bonds. (Very few naturally occurring fatty acids contain trans double bonds.) The presence of cis double bonds has an important effect on the melting point of the fatty acid. Cis double bonds form rigid kinks in the fatty acid chains (remember that there is no rotation around a double bond), and the result is that unsaturated fatty acids can not line up very well to give a regularly arranged crystal structure. Saturated fatty acids, on the other hand, line up in a very regular manner. The result of this is that saturated fatty acids have high melting points and are usually solids at room temperature. Unsaturated fatty acids, however, have low melting points and are usually liquids at room temperature. The names, structures, and melting points of some common fatty acids are shown in the table below. Structures of Common -

Lauric Acid Versus Palmitic Acid: Effects on Adipose Tissue Inflammation, Insulin Resistance, and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Obesity

biology Article Lauric Acid versus Palmitic Acid: Effects on Adipose Tissue Inflammation, Insulin Resistance, and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Obesity Viswanathan Saraswathi 1,2,*, Narendra Kumar 1,2, Thiyagarajan Gopal 1,2, Saumya Bhatt 1,2, Weilun Ai 1,2 , Carmen Ma 1,2, Geoffrey A. Talmon 3 and Cyrus Desouza 1,2 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolism, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198, USA; [email protected] (N.K.); [email protected] (T.G.); [email protected] (S.B.); [email protected] (W.A.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (C.D.) 2 VA Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, NE 68105, USA 3 Department of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-402-995-3033; Fax: +1-402-449-0604 Received: 27 August 2020; Accepted: 14 October 2020; Published: 22 October 2020 Simple Summary: The aim of this study was to compare the effect of palmitic acid (PA), a long-chain fatty acid, and lauric acid (LA), a medium-chain fatty acid, on obesity-related metabolic disorders. We used a mouse model of diet-induced obesity and fed them a modified high fat diet supplemented with 3% PA or LA for 12 wk. An LA diet led to an increase in visceral fat mass with a reduction in inflammation compared to the PA diet. We also noted that PA significantly increased systemic insulin resistance whereas LA showed only a trend towards an increase compared to lean control mice. -

Lipids Glycerol

Chapter 5 The Lipids: Triglycerides Phospholipids Sterols Lipids A class of nutrients that includes: Triglycerides A combination of one molecule of glycerol and three molecules of fatty acids Phospholipids Sterols Glycerol 1 Acetic Acid Methyl Acid end end Fig. 5-1, p. 140 Characteristics of Fatty Acids Length of the carbon chain: Long-chain fatty acids are found primarily in meat, fish, and vegetable oils Short-chain fatty acids are found primarily in dairy products Fatty Acids Length of carbon chain: Stearic acid – 18-carbon, saturated Simplified structure 2 Characteristics of Fatty Acids (2) Degree of unsaturation: Saturated fatty acids carry the maximum number of hydrogen atoms Unsaturated fatty acids have varying numbers of hydrogen atoms missing, resulting in double bonds An impossible chemical structure Oleic acid – 18-carbon, monounsaturated Linoleic acid – 18-carbon, polyunsaturated Characteristics of Fatty Acids (3) Location of double bonds: Omega number: Omega-3 fatty acid Omega-6 fatty acid 3 Essential Fatty Acids Linolenic acid, an omega-3 fatty acid Omega carbon Acid end Methyl end Linoleic acid, an omega-6 fatty acid Acid end Omega carbon Methyl end Fig. 5-2, p. 142 Condensation of Glycerol & Fatty Acids to Form a Triglyceride Glycerol + 3 fatty acids Triglyceride + 3 water molecules An H atom from glycerol and an OH Three fatty acids attached to a group from a fatty acid combine to glycerol form a triglyceride and create water, leaving the O on the yield water. In this example, all glycerol and the C at the acid end of three fatty acids are stearic acid, each fatty acid to form a bond.