Chapter 6 the Adaptive Musician: the Case of Peter Hook and Graham Massey Ewa Mazierska and Tony Rigg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the High Court of Justice Claim No Hc13 Fo4688 Chancery Division Intellectual Property Between

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE CLAIM NO HC13 FO4688 CHANCERY DIVISION INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY BETWEEN; WARNER RECORDS 90 LIMITED STEPHEN MORRIS GILLIAN GILBERT BERNARD SUMNER DEBORAH WOODRUFF PETER HOOK - and - JULIA ADAMSON D E F E N C E OF JULIA ADAMSON DEFENDANT Clauses 9 (a) and (b), 21, 22, 23, 24 I was an employee at Strawberry Studios from 1984 to 1989. When Strawberry Studios closed down the staff were busy clearing out the building. There were at least 20,000 copy masters from various bands and the artistes or their agents. They were contacted as to whether they wished to buy the tapes from the Strawberry library because they were clearing out. Mostly the artistes already had their own copies and said Strawberry should dispose of them. Some asked for the copy masters and these were handed over. The remaining copy masters were consigned to the skips. A colleague David Drennan was assigned the task of contacting as many of the clients as possible about their tapes. In the case of Factory Records, David Drennan remembers that they only asked for The Happy Mondays tapes and did not want any others. (see copy email ‘Dave Drennan’) Later I discovered that Factory Records had parted company with Joy Division/New Order. I felt that the tapes of Martin Hannett's work i.e. the ones he produced should not be destroyed. That is why I removed them from the skip and rescued them from landfill. When Warners were threatening court action I contacted Nick Turnbull (see copy email ‘Nick Turnbull’) who had been the owner of Strawberry Studios and who closed it down. -

Press 1 April 2021 the Famous Artists Behind History's Greatest Album

CNN Style The famous artists behind history's greatest album covers Leah Dolan 1 April 2021 The famous artists behind history's greatest album covers Throughout the 20th-century record sleeves regularly served as canvases for some of the world's most famous artists. From Andy Warhol's electric yellow banana on the cover of The Velvet Underground & Nico's 1967's debut album, to the custom-sprayed Banksy street art that fronted Blur's 2003 "Think Tank," art has long been used to round out the listening experience. A new book, "Art Sleeves," explores some of the most influential, groundbreaking and controversial covers from the past forty years. "This is not a 'history of album art' type book," said the book's author, DJ and arts writer DB Burkeman over email. Instead, he says the book is a "love letter" to visual art and music culture. For the 45th anniversary of "The Velvet Underground & Nico" in 2012, British artist David Shrigley illustrated a special edition reissue cover for Castle Face Records. Image: David Shrigley/Rizzoli Featured records span genres and decades. Among them are Warhol's cover for The Rolling Stones' 1971 album "Sticky Fingers," featuring the now-famous close-up of a man's crotch (often assumed, incorrectly, to be frontman Mick Jagger in tight jeans) as well as an array of seminal covers designed by graphic designer Peter Saville, co-founder of influential Manchester-based indie label Factory Records. Despite having relatively little art direction experience under his belt, Saville was behind iconic covers such as Joy Division's "Unknown Pleasures" (1979), depicting the radio waves emitted by a rotating star, and the brimming basket of wilting roses -- a muted reproduction of a 1890 painting by French artist Henri Fantin-Latour -- that fronted New Order's "Power, Corruption & Lies" (1983). -

Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur Gmbh the World's Oldest Accordion

MADE IN GERMANY Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH The world’s oldest accordion manufacturer | Since 1852 Our “Weltmeister” brand is famous among accordion enthusiasts the world over. At Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH, we supply the music world with Weltmeister solo, button, piano and folklore accordions, as well as diatonic button accordions. Every day, our expert craftsmen and accordion makers create accordions designed to meet musicians’ needs. And the benchmark in all areas of our shop is, of course, quality. 160 years of instrument making at Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH in Klingenthal, Germany, are rooted in sound craftsmanship, experience and knowledge, passed down carefully from master to apprentice. Each new generation that learns the trade of accordion making at Weltmeister helps ensure the longevity of the company’s incomparable expertise. History Klingenthal, a centre of music, is a small town in the Saxon Vogtland region, directly bordering on Bohemia. As early as the middle of the 17th century, instrument makers settled down here, starting with violin makers from Bohemia. Later, woodwinds and brasswinds were also made here. In the 19th century, mouth organ ma- king came to town and soon dominated the townscape with a multitude of workshops. By the year 1840 or thereabouts, this boom had turned Klingenthal into Germany’s largest centre for the manufacture of mouth organs. Production consolidation also had its benefits. More than 30 engineers and technicians worked to stre- Accordion production started in 1852, when Adolph amline the instrument making process and improve Herold brought the accordion along from Magdeburg. quality and customer service. A number of inventions At that time the accordion was a much simpler instru- also came about at that time, including the plastic key- ment, very similar to the mouth organ, and so it was board supported on two axes and the plastic and metal easily reproduced. -

Pre-Pedidos: 11 - Octubre - 2019

CLICK AQUÍ PARA VISITAR EL INDICE CON TODOS LOS LISTADOS DISPONIBLES descuento del 9% para pedidos de este listado recibidos hasta el 18 - octubre - 2019 inclusive PRE-PEDIDOS: 11 - OCTUBRE - 2019 WORMHOLE GRUMPTRONIX - NIGHTMOVES # 3: 14.30 € WISDOM DIRTY SHEETS / LOVEFIX / NIGHTMOVES / COSMIC GLIDE 13.01 € WORMO2.3 12" TECHNO / HOUSE / ACID / REPRESS: 02 - Diciembre - 2019 NLD ELECTRO As with the previous 2 releases in the 3-part Grumptronix series, the A-side features the duo's most sought A1 after tracks from their back catalogue. This concluding chapter features the futuristic-funk and vocoder- laden 'Dirty Sheets', an enigmatic electro classic that has been become almost impossible to find for collectors. This is followed by the travelling and morphing sounds of 'Lovefix' - a track that is long regarded A2 as one of the greatest electro tracks of the era. As with the rest of the series, the two reissue tracks are featured alongside 2 previously unheard, unreleased productions that were created during the same time period, at the same studio in Tampa, Florida. The first previously unreleased track is 'Nightmoves', a B1 potential future classic. An immediate call to the dancefloor that provides the discerning DJ with something to break through even the most monotonous of sets. The final track of the series is 'Cosmic Glide', a bouncy rhythm with purple, funk-fuelled keys that are equal parts future and past. Nightmoves #3 B2 is last in the series, but by absolutely no means least. WORMO2's transmission is complete, over and out 12.80 € MODEIGHT VENDA - OVIO EP 11.65 € MODEIGHT008 12" HOUSE / MINIMAL-HOUSE Vinyl Only / 180 grams UKR Following his recent Australian tour, Modeight label mastermind Silat Beksi now connects the dots between A1 Europe's thriving minimal underground and the emerging scene down under by showcasing Aussie modular specialist Venda for Modeight's 8th vinyl release. -

Native Instruments Releases the Second Installment in the EVERYBODY DJ Video Series

Native Instruments releases the second installment in the EVERYBODY DJ video series Dance music pioneer A Guy Called Gerald discusses the cultural link between new technology and the evolution of electronic music Berlin, September 18, 2014 – Native Instruments today continues the EVERYBODY DJ video series with the second installment featuring electronic music legend A Guy Called Gerald. The video features Gerald describing how innovative technology plays an important role in defining DJ culture and how mobile apps like TRAKTOR DJ for iPad and iPhone are creating new performance possibilities and diversifying relationships to digital music. An icon in his own league, A Guy Called Gerald has been an instrumental figure in the development of techno, acid house, jungle, and drum and bass in the UK since the late 1980s. The video captures Gerald’s view on the close relationship between technology and electronic music – reflecting on previous audio limitations with vinyl, and how digital technology has changed how he listens to, DJs, and creates music. Filmed in London at the premier of RELEASE, a documentary on House Shuffling in Britain, the video shows Gerald as he explains why the physical manipulation of waveforms on apps like TRAKTOR DJ for iPad and iPhone has given rise to completely new ways of DJing. Gerald can be seen mixing, beat jumping, and loop slicing live with TRAKTOR DJ for iPad – a tool that has had a particular impact on his DJing. Still underway, the first video in the EVERYBODY DJ series introduced the MIX. WIN. BERLIN! competition where Native Instruments asks “What would you play?” Anyone can enter to win a VIP weekend in Berlin by recording and uploading a mix to Mixcloud using TRAKTOR DJ, and tagging it with the #whatwouldyouplay hashtag. -

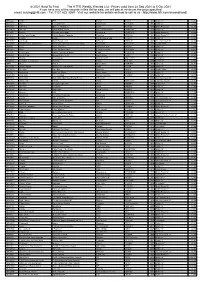

2021 Hard to Find the HTFR Weekly Wanted List

© 2021 Hard To Find The HTFR Weekly Wanted List - Prices valid from 28 Sep 2021 to 5 Oct 2021 If you have any of the records in this list for sale, we will pay at minimum the price specified email: [email protected] - Tel: 0121 622 3269 - Visit our website for details on how to sell to us - http://www.htfr.com/secondhand/ MR26666 100Hz EP3 Pacific FIC020 1999 British 12" £4.00 MR75274 16B Trail Of Dreams Stonehouse STR12008 1995 British 12" £2.00 MR18837 2 Funky 2 Brothers And Sisters Logic FUNKY2 1994 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR759025 3rd Core Mindless And Broken WEA International Inc. SAM00291 2000 British 12" £2.00 MR12656 4 Hero Cooking Up Ya Brain Reinforced RIVET1216 1992 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR14089 A Guy Called Gerald 28 Gun Badboy / Paranoia Columbia XPR1684 1992 British Promo 12" £8.00 MR169958 A Sides Punks Strictly Underground STUR74 1996 British 12" £4.00 MR353153 Aaron Carl Down (Resurrected) Wallshaker WMAC30 2009 American Import 12" £2.00 MR759966 Academy Of St. Martin-in-the-F Amadeus (Original Soundtrack Recording) Metronome 8251261ME 1984 Double Album £2.00 MR4926 Acen Close Your Eyes Production House PNT034 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR12863 Acen Trip Ii The Moon Part 3 Production House PNT042RX 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR16291 Age Of Love Age Of Love (Jam & Spoon) React 12REACT9 1992 British 12" £7.00 MR44954 Agent Orange Sounds Flakey To Me Agent Orange AO001 1992 British 12" £8.00 MR764680 Akasha Cinematique Wall Of Sound WALLLP016 1998 Vinyl Album £1.00 MR42023 Alan Braxe & Fred Falke Running Vulture VULT001 2000 French -

Lancashire Arts

Degree Show edition Lancashire Arts A guide to events and exhibitions May - August 2019 INTRODUCTION WHAT’S ON The Faculty of Culture and the Creative Industries is excited to present the May pg 4-16 • Graham Massey and Toolshed Degree Show edition of the Lancashire Arts booklet, showcasing the amazing • Social Fusion Funnel • Worldwise Samba Drummers talent and dedication of our creative students, staff and collaborators. • Preston People’s Choir You will find an extensive programme of degree shows, performances, • Preston Scratch Band • Jay’s Jazz Jam exhibitions, workshops and events, appealing to a range of audiences – many • Preston People’s Choir • Border Morris Dancing of which are free to attend. We are also delighted to be hosting the second • Borders and Boundaries • Making Presence Felt Preston Jazz and Improvisation Festival during the first week in June, in • I’m Here • Tea Time Jazz partnership with Preston City Council and supported by Arts Council England. • FutureSound • Jazz Guitar Double Header The festival is set to bring Preston alive with jazz with performances and • Border Morris Dancing (until August) • Conga Drumming Course workshops led by internationally renowned artists as well as local musicians. • Preston Samba Dancers • A Day of Django • Rhythm Jam See our Degree Shows at their most vibrant, • Gondwana 10 • Embodying Health • Creative Prayer: Don’t Worry! save Thursday 13 June in your calendar! • Creative Prayer: Psalm 23 • Degree Shows • The Finale • Preston Samba Dancers This is the date of our Private View where you are welcome to join our students as • Sweet Charity they celebrate with friends, family and industry. -

Scanned Image

Compulsion are on our to promote their new Iohri and Sandra welcome you to album The Future ls Medium, out June 17th. Catch them in Leicester (The Charlotte, 20th) or W firstofall: Stoke (The Stage July 3rd). Done Lying Down return from a six week tour of . Nottingham Music. Industry. Week is a four day Europe with Killdozer and Chumbawamba with a event for budding musicians, promoters, sound re-recorded and remixed version on 7" and cd of THE mixers and DJs. Organised by Carlos Thrale of Can’t Be Too Certain from their Kontrapunkt _ u r I S Arnold & Carlton College, one of the few album on Immaterial Records. The cd format OLDEN FLEECE To colleges in the UK to award a BTEC in popular also features three exclusive John Peel session music, in conjunction with Confetti School Of tracks. A UK tour brings them to Leicester (The 105 Mansfield Road Nottingham ’ Recording Technology, Carlsboro Soundaalso Charlotte, July 3rd) and Derby (The Garrick, Traditional Cask Ales involved are the Warehouse Studios and East 4th). ’** Guest Beers "“* msterdam Midlands Arts. The four day event begins on Ambient Prog Rockers The Enid return with a Monday 22nd July comprising seminars and "‘.‘:-5-@5953‘:-5: ' string of summer dates prior to the release of Frankfurt £69 tin workshops led by professionals from all areas of their singles compilation Anarchy On 45. I I n I I - a u u ¢ u I I a n | n - o - | q | I q n I - Q - - - - I I I | ¢ | | n - - - , . , . the music industry, and evening gigs. -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent. -

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel B.S. Physics Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Evan Landon Wendel. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _______________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies May 9, 2008 Certified By: _____________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: _____________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 2 3 New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract This thesis explores the evolving nature of independent music practices in the context of offline and online social networks. The pivotal role of social networks in the cultural production of music is first examined by treating an independent record label of the post- punk era as an offline social network. -

Recordings by Artist

Recordings by Artist Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 10,000 Maniacs MTV Unplugged CD 1993 3Ds The Venus Trail CD 1993 Hellzapoppin CD 1992 808 State 808 Utd. State 90 CD 1989 Adamson, Barry Soul Murder CD 1997 Oedipus Schmoedipus CD 1996 Moss Side Story CD 1988 Afghan Whigs 1965 CD 1998 Honky's Ladder CD 1996 Black Love CD 1996 What Jail Is Like CD 1994 Gentlemen CD 1993 Congregation CD 1992 Air Talkie Walkie CD 2004 Amos, Tori From The Choirgirl Hotel CD 1998 Little Earthquakes CD 1991 Apoptygma Berzerk Harmonizer CD 2002 Welcome To Earth CD 2000 7 CD 1998 Armstrong, Louis Greatest Hits CD 1996 Ash Tuesday, January 23, 2007 Page 1 of 40 Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 1977 CD 1996 Assemblage 23 Failure CD 2001 Atari Teenage Riot 60 Second Wipe Out CD 1999 Burn, Berlin, Burn! CD 1997 Delete Yourself CD 1995 Ataris, The So Long, Astoria CD 2003 Atomsplit Atonsplit CD 2004 Autolux Future Perfect CD 2004 Avalanches, The Since I left You CD 2001 Babylon Zoo Spaceman CD 1996 Badu, Erykah Mama's Gun CD 2000 Baduizm CD 1997 Bailterspace Solar 3 CD 1998 Capsul CD 1997 Splat CD 1995 Vortura CD 1994 Robot World CD 1993 Bangles, The Greatest Hits CD 1990 Barenaked Ladies Disc One 1991-2001 CD 2001 Maroon CD 2000 Bauhaus The Sky's Gone Out CD 1988 Tuesday, January 23, 2007 Page 2 of 40 Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 1979-1983: Volume One CD 1986 In The Flat Field CD 1980 Beastie Boys Ill Communication CD 1994 Check Your Head CD 1992 Paul's Boutique CD 1989 Licensed To Ill CD 1986 Beatles, The Sgt -

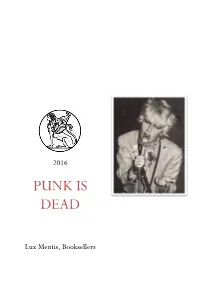

Punk Is Dead” Catalog Includes, the SST Records the Inventory Representing the “Punk Is Collection, C

2016 PUNK IS DEAD Lux Mentis, Booksellers Lux Mentis Booksellers specializes in fine press, artist books, first editions, Punk rock evolved over several and esoterica with a particular emphasis generations and manifestations of youth on challenging and unusual materials. culture beginning in the 1970s. Even after 40 years, punk subculture still We actively collaborate with archives demonstrates the capability to influence and special collections libraries to meet successive contemporary elements of the research and collecting needs of art, music, and fashion regardless of its public learning institutions, private, original intention to lambast conformity. independent libraries and collections with primary sources. Selected inventory in the “Punk is Dead” catalog includes, the SST Records The inventory representing the “Punk is Collection, c. 1979-1996; original Dead” collection is a retrospective artwork from famed punk artist, selection of critical primary source Raymond Pettibon; correspondence materials documenting the punk rock from Gordon Gano, original member of movement of the 1970s-1990s. The the Violent Femmes; and several unique collection illustrates the profound fanzine and alternative publications. subculture of punk from an artistic and politically fueled era from Los Angeles, Lux Mentis regularly features and New York, and London. showcases punk culture related materials at major ABAA book fairs and Please contact us for an appointment or continues to cultivate the acquisition of with questions regarding the inventory. subculture materials for research and collection development purposes. 110 Marginal Way #777 Portland, ME 04101 Member: ILAB/ABAA T. 207.329.1469 Email: [email protected] Front cover image: From the SST [email protected] Records Collection, detail of “Outcry” Web: http://www.luxmentis.com magazine Blog: http://www.asideofbooks.com Cataloged created by Kim Schwenk and edited by Ian Kahn 2 Ginn, Greg, Pettibon, Raymond, et al.