From Idealistic to Iconic Adelaide – an Enduring Nexus Between Urban Plan and Social Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bound for South Australia Teacher Resource

South Australian Maritime Museum Bound for South Australia Teacher Resource This resource is designed to assist teachers in preparing students for and assessing student learning through the Bound for South Australia digital app. This education resource for schools has been developed through a partnership between DECD Outreach Education, History SA and the South Australian Maritime Museum. Outreach Education is a team of seconded teachers based in public organisations. This app explores the concept of migration and examines the conditions people experienced voyaging to Australia between 1836 and the 1950s. Students complete tasks and record their responses while engaging with objects in the exhibition. This app comprises of 9 learning stations: Advertising Distance and Time Travelling Conditions Medicine at Sea Provisions Sleep Onboard The First 9 Ships Official Return of Passengers Teacher notes in this resource provide additional historical information for the teacher. Additional resources to support student learning about the conditions onboard early migrant ships can be found on the Bound for South Australia website, a resource developed in collaboration with DECD teachers and History SA: www.boundforsouthaustralia.net.au Australian Curriculum Outcomes: Suitability: Students in Years 4 – 6 History Key concepts: Sources, continuity and change, cause and effect, perspectives, empathy and significance. Historical skills: Chronology, terms and Sequence historical people and events concepts Use historical terms and concepts Analysis -

November 2019

Care Resilience Create Optimism Innovate Courage UHSnews Knowledge ISSUE: 7| TERM FOUR 2019 Inside this issue From our Principal, Mr David Harriss End of year Information Hello everyone, and welcome to our second-last newsletter for the year. Year 12 Exams are 2 Year 12 Graduation finished, all work has been submitted and our 2019 cohort can now relax and await their 4 final results just before Christmas. A final year 12 report will be coming home soon based School Sport 10 on school-based results. These grades will go through a standards moderation process and Mathematical Mindsets may be altered by the SACE Board, and their Externally Marked work (Exams, Investigations 11 etc.) needs to be added as well. I would like to take this opportunity to thank all of these Student Voice 16 students and their families for their contribution to Underdale High School and wish them Dental Program all the best in whatever endeavours they wish to pursue in the future. 19 Calendar Dates Plans for our $20million development are nearing completion, and some of these plans and images will be on our Website soon. I will let you know when this happens. It is envisaged Term 4 that building will start in the second half of next year and be completed by the end of 2021, Week 6 in readiness for the Year 7’s coming to Underdale High School. We are excited by both of these events, and they promise to build on our great school community. Wednesday 20th November - Year 12 Formal The last weeks of school are vital for our remaining students. -

Michael” to “Myrick”

GPO Box 464 Adelaide SA 5001 Tel (+61 8) 8204 8791 Fax (+61 8) 8260 6133 DX:336 [email protected] www.archives.sa.gov.au Special List GRG24/4 Correspondence files ('CSO' files) - Colonial, later Chief Secretary's Office – correspondence sent GRG 24/6 Correspondence files ('CSO' files) - Colonial, later Chief Secretary's Office – correspondence received 1837-1984 Series These are the major correspondence series of the Colonial, Description subsequently (from 1857) the Chief Secretary's Office (CSO). The work of the Colonial Secretary's Office touched upon nearly every aspect of colonial South Australian life, being the primary channel of communication between the general public and the Government. Series date range 1837 – 1984 Agency Department of the Premier and Cabinet responsible Access Records dated prior to 1970 are unrestricted. Permission to Determination access records dated post 1970 must be sought from the Chief Executive, Department of the Premier and Cabinet Contents Correspondence – “Michael” to “Myrick” Subjects include inquests, land ownership and development, public works, Aborigines, exploration, legal matters, social welfare, mining, transport, flora and fauna, agriculture, education, religious matters, immigration, health, licensed premises, leases, insolvencies, defence, police, gaols and lunatics. Note: State Records has public access copies of this correspondence on microfilm in our Research Centre. For further details of the correspondence numbering system, and the microfilm locations, see following page. 2 December 2015 GRG 24/4 (1837-1856) AND GRG 24/6 (1842-1856) Index to Correspondence of the Colonial Secretary's Office, including some newsp~per references HOW TO USE THIS SOURCE References Beginning with an 'A' For example: A (1849) 1159, 1458 These are letters to the Colonial Secretary (GRG 24/6) The part of the reference in brackets is the year ie. -

40 Great Short Walks

SHORT WALKS 40 GREAT Notes SOUTH AUSTRALIAN SHORT WALKS www.southaustraliantrails.com 51 www.southaustraliantrails.com www.southaustraliantrails.com NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Sturt River Stony Desert arburton W Tirari Desert Creek Lake Eyre Cooper Strzelecki Desert Lake Blanche WESTERN AUSTRALIA WESTERN Outback Great Victoria Desert Lake Lake Flinders Frome ALES Torrens Ranges Nullarbor Plain NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Lake Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Gairdner Sturt 40 GREAT SOUTH AUSTRALIAN River Stony SHORT WALKS Head Desert NEW SOUTH W arburton of Bight W Trails Diary date completed Trails Diary date completed Tirari Desert Creek Lake Gawler Eyre Cooper Strzelecki ADELAIDE Desert FLINDERS RANGES AND OUTBACK 22 Wirrabara Forest Old Nursery Walk 1 First Falls Valley Walk Ranges QUEENSLAND A 2 First Falls Plateau Hike Lake 23 Alligator Gorge Hike Blanche 3 Botanic Garden Ramble 24 Yuluna Hike Great Victoria Desert 4 Hallett Cove Glacier Hike 25 Mount Ohlssen Bagge Hike Great Eyre Outback 5 Torrens Linear Park Walk 26 Mount Remarkable Hike 27 The Dutchmans Stern Hike WESTERN AUSTRALI WESTERN Australian Peninsula ADELAIDE HILLS 28 Blinman Pools 6 Waterfall Gully to Mt Lofty Hike Lake Bight Lake Frome ALES 7 Waterfall Hike Torrens KANGAROO ISLAND 0 50 100 Nullarbor Plain 29 8 Mount Lofty Botanic Garden 29 Snake Lagoon Hike Lake 25 30 Weirs Cove Gairdner 26 Head km BAROSSA NEW SOUTH W of Bight 9 Devils Nose Hike LIMESTONE COAST 28 Flinders -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals. -

Place Names of South Australia: W

W Some of our names have apparently been given to the places by drunken bushmen andfrom our scrupulosity in interfering with the liberty of the subject, an inflection of no light character has to be borne by those who come after them. SheaoakLog ispassable... as it has an interesting historical association connectedwith it. But what shall we say for Skillogolee Creek? Are we ever to be reminded of thin gruel days at Dotheboy’s Hall or the parish poor house. (Register, 7 October 1861, page 3c) Wabricoola - A property North -East of Black Rock; see pastoral lease no. 1634. Waddikee - A town, 32 km South-West of Kimba, proclaimed on 14 July 1927, took its name from the adjacent well and rock called wadiki where J.C. Darke was killed by Aborigines on 24 October 1844. Waddikee School opened in 1942 and closed in 1945. Aboriginal for ‘wattle’. ( See Darke Peak, Pugatharri & Koongawa, Hundred of) Waddington Bluff - On section 98, Hundred of Waroonee, probably recalls James Waddington, described as an ‘overseer of Waukaringa’. Wadella - A school near Tumby Bay in the Hundred of Hutchison opened on 1 July 1914 by Jessie Ormiston; it closed in 1926. Wadjalawi - A tea tree swamp in the Hundred of Coonarie, west of Point Davenport; an Aboriginal word meaning ‘bull ant water’. Wadmore - G.W. Goyder named Wadmore Hill, near Lyndhurst, after George Wadmore, a survey employee who was born in Plymouth, England, arrived in the John Woodall in 1849 and died at Woodside on 7 August 1918. W.R. Wadmore, Mayor of Campbelltown, was honoured in 1972 when his name was given to Wadmore Park in Maryvale Road, Campbelltown. -

Cit!J If Mefaije..Ftertt-'Y'e ~T-Er

Jtems recomluJ!,u<J~"f"r inc[usicn on a Cit!J ifMefaiJe..ftertt-'Y'e ~t-er ';Dp_artmeat ff CiYJ Pfannitf!p Sp_temPer l'SJ • • • • THE CITY OF ADELAIDE HERITAGE STUDY ITFMS RECOMMENDED FOR INCLUSION ON A CITY OF ADELAIDE HERITAGE REGISTER BY THE LORD MAYOR'S HERITAGE ADVISORY COMMITTEE VOLlME 1 GAWLER WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 2 HINDMARSH WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 3 GREY WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 4 YOUNG WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 5 ROBE WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 6 MACDONNELL WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 7 PARK IANDS (ALL ITEMS oursIDE THE TERRACES - NOT WITHIN TOON ACRES) VOLU1E 8 SUMMARY ANALYSIS OF THE PROPOSED CITY OF ADELAIDE HERITAGE REGISTER. Department of City Planning September 1983. MC: 2 :DCP lOD/C (26/9/83) VOLlME 7 PARK LANDS (ALL ITavtS ourSIDE THE TERRACES - NOT WITHIN TOWN ACRES) 2:DCP10D/D7 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLlME 7 - PARK LANDS (ALL ITEMS OUTSIDE THE TERRACES - NOT WI THIN TOWN ACRES) PAGE MAP OF THE CITY OF ADELAIDE Showing Location of Items Within the Park Lands (Outside the Terraces - Not Within Town Acres) 1 S lMMARY DOCUMENTATION OF ITEMS 2 Item Number as------ appearing in Volume 8 Table Item and Address 312 2 Parliament House North Terrace 313 4 Constitutional Museum North Terrace 314 6 S.A. Museum, East Wing North Terrace 315 8 S.A. Museum, North Wing North Terrace 316 10 Fmr. Mounted Police Barracks, Armoury and Arch Off North Terrace 317 13 Fmr. Destitute Asylum (Chapel, Store, Lying-in Hospital & Female Section) Kintore Avenue 318 18 State Library - Fmr. -

Rethinking Modern Architecture – Caroline Cosgrove

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Flinders Academic Commons Rethinking Modern Architecture – Caroline Cosgrove Rethinking Modern Architecture: HASSELL’s Contribution to the Transformation of Adelaide’s Twentieth Century Urban Landscape Caroline Cosgrove Abstract There has been considerable academic, professional and community interest in South Australia’s nineteenth century built heritage, but less in that of the state’s twentieth century. Now that the twenty-first century is in its second decade, it is timely to attempt to gain a clearer historical perspective on the twentieth century and its buildings. The architectural practice HASSELL, which originated in South Australia in 1917, has established itself nationally and internationally and has received national peer recognition, as well as recognition in the published literature for its industrial architecture, its education, airport, court, sporting, commercial and performing arts buildings, and the well-known Adelaide Festival Centre. However, architectural historians have generally overlooked the practice’s broader role in the development of modern architecture until recently, with the acknowledgement of its post-war industrial work.1 This paper explores HASSELL’s contribution to the development of modern architecture in South Australia within the context of growth and development in the twentieth century. It examines the need for such studies in light of heritage considerations and presents an overview of the firm’s involvement in transforming the urban landscape in the city and suburbs of Adelaide. Examples are given of HASSELL’s mid-twentieth century industrial, educational and commercial buildings. This paper has been peer reviewed 56 FJHP – Volume 27 ‐2011 Figure 1: Adelaide’s urban landscape with the Festival Centre in the middle distance. -

2006 007.Pdf

No. 7 383 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE www.governmentgazette.sa.gov.au PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ALL PUBLIC ACTS appearing in this GAZETTE are to be considered official, and obeyed as such ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 2 FEBRUARY 2006 CONTENTS Page Page Appointments, Resignations, Etc...............................................384 Proclamations ............................................................................ 419 Architects Act 1939—Register..................................................385 Public Trustee Office—Administration of Estates .................... 438 Corporations and District Councils—Notices............................434 Rail Safety Act 1996—Notice................................................... 417 Development Act 1993—Notices..............................................395 Electoral Act 1985—Notice ......................................................410 REGULATIONS Environment Protection Act 1993—Notice...............................405 Summary Offences Act 1953 (No. 16 of 2006) ..................... 420 Fisheries Act 1982—Notice ......................................................410 Senior Secondary Assessment Board of South Harbors and Navigation Regulations 1994—Notice..................410 Australia Act 1983 (No. 17 of 2006).................................. 422 Land and Business (Sale and Conveyancing) Act 1994— Natural Resources Management Act 2004 Notice ....................................................................................410 (No. 18 of 2006)................................................................ -

For GRG 24/90 Miscellaneous Records of Historical Interest

GPO Box 464 Adelaide SA 5001 Tel (+61 8) 8204 8791 Fax (+61 8) 8260 6133 DX:336 [email protected] www.archives.sa.gov.au Special List GRG 24/90 Miscellaneous records of historical interest, artificial series - Colonial Secretary's Office, Governor's Office and others Series This series consists of miscellaneous records from Description various government agencies, namely the Colonial Secretary's Office and the Governor's Office, from 1837 - 1963. Records include correspondence between the Governor and the Colonial Secretary, correspondence between the Governor and Cabinet, and correspondence of the Executive Council. Also includes records about: hospitals, gaols, cemeteries, courts, the Surveyor-General's Office, harbours, Botanic Gardens, Lunatic Asylum, Destitute Board, exploration, police and military matters, Chinese immigration, Aboriginal people, marriage licences, prostitution, the postal service, the Adelaide Railway Company, agriculture, churches, and the Admella sinking. The items in this artificial series were allocated a number by State Records. Series date range 1837 - 1963 Agencies Office of the Governor of South Australia and responsible Department of the Premier and Cabinet Access Open. Determination Contents Arranged alphabetically by topic. A - Y State Records has public access copies of this correspondence on microfilm in our Research Centre. 27 May 2016 INDEX TO GRG 24/90, MISCELLANEOUS RECORDS SUBJECT DESCRIPTION REFERENCE NO. ABERNETHY, J. File relating to application GRG 24/90/86 by J. Abernethy, of Wallaroo Bay, for a licence for an oyster bed. Contains letter from J.B. Shepherdson J.P., together with a chart of the bed. 24 April, 1862. ABORIGINES Report by M. Moorhouse on GRG 24/90/393 O'Halloran's expedition to the Rufus. -

River Torrens Linear Park - Eastern Section Draft Management Plan

River Torrens Linear Park - Eastern Section Draft Management Plan Lead Consultant URPS Sub-Consultants EBS Tonkin Swanbury Penglase Consultant Project Manager Geoff Butler, Senior Associate, URPS Suite 12/154 Fullarton Road (cnr Alexandra Avenue) ROSE PARK, SA 5067 Tel: (08) 8333 7999 Fax: (08) 8332 0017 Email: [email protected] Website: www.urps.com.au River Torrens Linear Park Management Plan- Eastern Section Contents Contents Contents 2 Executive Summary 4 1.0 Introduction 10 1.1. Background to the Project 10 1.2. Project Process 11 2.0 Objectives 13 3.0 Vision and Guiding Principles 14 4.0 Management Directions 16 5.0 The Role of the River Torrens Linear Park 17 5.1. Background Discussion 17 5.2. Feedback 19 5.3. Management Directions 20 6.0 The Management Framework 22 6.1. Background Discussion 22 6.2. Feedback 25 6.3. Management Directions 26 7.0 Safety and Risk Management 29 7.1. Background Discussion 29 7.2. Feedback 29 7.3. Management Directions 30 8.0 Meeting Recreation Needs 32 8.1. Background Discussion 32 8.2. Feedback 35 8.3. Management Directions and Strategies 36 9.0 Maximising Environmental Performance 41 9.1. Background Discussion 41 9.2. Feedback 47 9.3. Management Directions and Strategies 48 River Torrens Linear Park Management Plan- Eastern Section Contents 10.0 Acknowledging Cultural Values 53 10.1. Background Discussion 53 10.2. Feedback 54 10.3. Management Directions 54 11.0 Development Within/Adjacent to the Linear Park 55 11.1. Background Discussion 55 11.2. Feedback 57 11.3. -

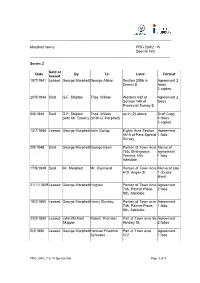

Morphett Family PRG 239/2 -15 Special Lists ______

________________________________________________________________________ Morphett family PRG 239/2 -15 Special lists ______________________________________________________________________ Series 2 S Sold or Date By To Land Format leased 19/7/1841 Leased George Morphett George Alston Section 2086 in Agreement 2 District B folios 2 copies 20/5/1844 Sold G.F. Shipton Thos. Wilson Western half of Agreement 2 Section 145 of folios Provincial Survey B 5/6/1844 Sold G.F. Shipton Thos. Wilson as in (2) above Draft Copy (with Mr. Brown) (With G. Morphett) 4 folios 2 copies 13/7/1844 Leased George Morphett John Gollop Eighty Acre Section Agreement 5515 of Para Special 1 folio Survey 2/9/1848 Sold George Morphett George Bean Portion of Town Acre Memo of 755, Strangways agreement Terrace, Nth. 1 folio Adelaide. 17/5/1849 Sold Mr. Morphett Mr. Raymond Portion of Town Acre Memo of sale 410, Angas St. 1 double sheet 21/11/1849 Leased George Morphett Hughes Portion of Town Acre Agreement 746, Palmer Place, 2 folio Nth. Adelaide 19/2/1850 Leased George Morphett Henry Stuckey Portion of Town acre Agreement 746, Palmer Place, 1 folio Nth. Adelaide. 23/2/1850 Leased John Michael Robert Thornber Part of Town acre 56, Agreement Skipper Hindley St. 2 folios 2/3/1850 Leased George Morphett Herman Friedrick Part of Town acre Agreement Schrader 572 1 folio PRG 239/2, 7 & 15 Special lists Page 1 of 9 ________________________________________________________________________ 30/1/1854 Leased George Morphett Nathaniel Summers Part of Town acre Ag reement 755, Strangways 1 folio Terrace, Nth. Adelaide 14/6/1850 Leased Robert Thornber John Dickins + Part of Town acre 56 Agreement George Griffin 1 double sheet 26/6/1850 Sold George Morphett Henry Jessop Part of Town acre Memo of 998, Melbourne St.