Herbert Spencer, the Brooklyn Ethical Association, and the Integration of Moral Philosophy and Evolution in the Victorian Trans-Atlantic Community Christopher R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

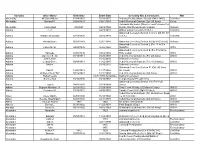

Surname Given Name Birth Date Death Date Cemetery Site & Comments

Surname Given Name Birth Date Death Date Cemetery Site & Comments. War Abernathy William Wilkins 11/24/1825 02/15/1875 Bethany Presby (Home Guard) (1861-1865) Civil War Abernathy Garland P. 03/08/1931 03/01/1984 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Cpl US Army) Korea Rehoboth Methodist (Sherrils Ford/Catawba Co) Abernathy Jimmy Edd 03/20/47 02/02/1969 Bronze Star/Purple Heart) Vietnam Vietnam Adams J. P. 04/25/1881 Willow Valley Cemetery (C.S.A.) Civil War Oakwood Cemetery Section C (Co C 4th NC Inf Adams William McLelland 07/13/1838 02/02/1918 C.S.A.) Civil War Adams Ronald Elam 06/28/1943 12/01/1988 Oakwood Cemetery Section Q (Sp 4 US Army) Vietnam Oakwood Cemetery Section L (Pvt 13 Inf Co Adams Calvin M. Sr. 04/24/1889 05/06/1968 MGOTS) WW I Oakwood Cemetery Section E (Pvt STU Army Adams Talmage 03/05/1899 09/02/1969 TNG Corps) WW I Adams Clarence E., Sr. 08/19/1911 08/20/1993 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Pvt US Army) WW II Adams John Lester 01/15/2010 Belmont Cemetery Adams Leland Orville 09/04/1914 11/02/1987 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Tec 4 US Army) WW II Adams Melvin 04/19/2012 Belmont Cemetery Oakwood Cemetery Section R (Cpl US Army Adams Paul K. 12/20/1919 11/17/1992 Air Corps) WW II Adams William Alfred "Bill" 07/26/1923 12/11/1998 Iredell Memorial Gardens (US Army) WW II Adams Robert Lewis 08/31/1991 burial date Belmont Cemetery Adams Stamey Neil 10/14/1936 10/14/1992 Temple Baptist Pfc US Army Oakwood Cemetery Section Vet (Tec4 US Adcox Floyd A. -

Trademarklist Week 41 / 2020

TRADEMARKLIST WEEK 41 / 2020 TM EXACT TM SIMILAR OWNER SERIAL TYPE STATUS FILED ON REGISTERED ON INSTITUTION KK magsun - Shenzhen Anjun Business Consulting Co., Ltd. 18319404 Word Filed 2020-10-10T12:00:00.000Z - EM l' unperfect - Pinheiro Americo 18319427 Word Filed 2020-10-10T12:00:00.000Z - EM LIUPMWE - Changsha Yongmai Electronic Commerce Co., Ltd. 18319399 Word Filed 2020-10-10T12:00:00.000Z - EM JOYSPELS - Wang Qinyi 18319400 Word Filed 2020-10-10T12:00:00.000Z - EM Tancefair - Shenzhen Tianchenyuan Technology Co., Ltd. 18319280 Word Filed 2020-10-10T12:00:00.000Z - EM KARETT - Zuo Xiaoshan 18319951 Word Filed 2020-10-10T12:00:00.000Z - EM LENILOVE - Mackauer Kristina 18319269 Word Filed 2020-10-10T12:00:00.000Z - EM Bifscebn - Wang Youbao 18319948 Word Filed 2020-10-10T12:00:00.000Z - EM Index - Rovo GmbH 18319555 Word Filed 2020-10-09T12:00:00.000Z - EM C|R|OWN - Leather Crown srl 18319215 Word Filed 2020-10-09T12:00:00.000Z - EM CHINATOWN MARKET - Cherm LLC 18319372 Word Filed 2020-10-09T12:00:00.000Z - EM WEARIO - Weario B.V. 18319578 Word Filed 2020-10-09T12:00:00.000Z - EM Orlando Owen - Authentic Power Systems, Inc. 18319635 Word Filed 2020-10-09T12:00:00.000Z - EM THE RISE OF THE PHOENIX - Parvar Navid 18319914 Word Filed 2020-10-09T12:00:00.000Z - EM passt eh. - Brandstetter Viktoria 18319889 Word Filed 2020-10-09T12:00:00.000Z - EM GRIFEMA - IBERGRIF GRIFERÍAS S.L. 18319299 Word Filed 2020-10-09T12:00:00.000Z - EM COSMOS BABY - Iliakhova Oksana 18319318 Word Filed 2020-10-09T12:00:00.000Z - EM Lilhowcy - Shenzhen Shangpinhui Information Technology Co., Ltd. -

The Routledge History of Literature in English

The Routledge History of Literature in English ‘Wide-ranging, very accessible . highly attentive to cultural and social change and, above all, to the changing history of the language. An expansive, generous and varied textbook of British literary history . addressed equally to the British and the foreign reader.’ MALCOLM BRADBURY, novelist and critic ‘The writing is lucid and eminently accessible while still allowing for a substantial degree of sophistication. The book wears its learning lightly, conveying a wealth of information without visible effort.’ HANS BERTENS, University of Utrecht This new guide to the main developments in the history of British and Irish literature uniquely charts some of the principal features of literary language development and highlights key language topics. Clearly structured and highly readable, it spans over a thousand years of literary history from AD 600 to the present day. It emphasises the growth of literary writing, its traditions, conventions and changing characteristics, and also includes literature from the margins, both geographical and cultural. Key features of the book are: • An up-to-date guide to the major periods of literature in English in Britain and Ireland • Extensive coverage of post-1945 literature • Language notes spanning AD 600 to the present • Extensive quotations from poetry, prose and drama • A timeline of important historical, political and cultural events • A foreword by novelist and critic Malcolm Bradbury RONALD CARTER is Professor of Modern English Language in the Department of English Studies at the University of Nottingham. He is editor of the Routledge Interface series in language and literary studies. JOHN MCRAE is Special Professor of Language in Literature Studies at the University of Nottingham and has been Visiting Professor and Lecturer in more than twenty countries. -

![Evolution and Personality [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6369/evolution-and-personality-1-96369.webp)

Evolution and Personality [1]

Evolution and Personality [1] James Gibson Hume (1922) Classics in the History of Psychology An internet resource developed by Christopher D. Green , ISSN 1492-3173 (Return to C lassics i ndex ) Evolution and Personality [1] James Gibson Hume (1922) First published in Philosophical Essays Presented to John Watson (pp. 298-330). : Queen's University.[*] Posted October 2001 Spencer in his Data of Ethics treated his subject from several successive standpoints entitled, The Physical, The Biological, The Psychological, the Sociological. He also attempted to co-ordinate all these various stages into what he termed a Synthetic Philosophy. This would give a fifth standpoint, the Philosophical. These five terms might be used to describe several different types of evolutionary theory. Let us note how these arose, that is, let us trace the evolution of evolutionary theory. Physical Evolution. Early Greek speculation was dominated by this standpoint which found its culmination in the Atomists. Among these Empedocles is noteworthy. He is quoted in the article 'Evolution' in the Encyclopaedia Britannica by J. Sully and T. H. Huxley. After a general Cosmology dealing with the formation of the Cosmos from the four original elements, fire, air, earth, water, by love and discord (attraction and repulsion) he proceeds to treat of the first origin of plants and of animals including man. As the original elements entered into various combinations there arose curious aggregates, heads without [p. 299] necks, arms without shoulders. These got strangely combined. Men's heads on oxen's shoulders, heads of .oxen on men's bodies, etc. Most of these combinations could not survive and so disappeared. -

The Ideological Origins of the Population Association of America

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield Sociology & Anthropology Faculty Publications Sociology & Anthropology Department 3-1991 The ideological origins of the Population Association of America Dennis Hodgson Fairfield University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/sociologyandanthropology- facultypubs Archived with permission from the copyright holder. Copyright 1991 Wiley and Population Council. Link to the journal homepage: (http://wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/padr) Peer Reviewed Repository Citation Hodgson, Dennis, "The ideological origins of the Population Association of America" (1991). Sociology & Anthropology Faculty Publications. 32. https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/sociologyandanthropology-facultypubs/32 Published Citation Hodgson, Dennis. "The ideological origins of the Population Association of America." Population and Development Review 17, no. 1 (March 1991): 1-34. This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ideological Origins of the Population Association of America DENNIS HODGSON THE FIELD OF POPULATION in the United States early in this century was quite diffuse. There were no academic programs producing certified demographers, no body of theory and methods that all agreed constituted the field, no consensus on which population problems posed the most serious threat to the nation or human welfare more generally. -

Southern Medical and Surgical Journal

SOUTHERN MEDICAL AND SURGICAL JOURNAL. EDITED BY HENRY F. CAMPBELL, A.M., M. D., GEORGIA PROKES-OR OK BPECIAL AND COMPARATIVE ANATOMY IN TBI MEDICAL COLLEGK OF ROBERT CAMPBELL, A.M..M.D., DBMOSrtTRATOB OF ANATOMY IN THE MEDICAL COLLEGE MEPICAL COLLEGE OF GEORGIA. YOL. XIV.—1858.—NEW SERIES. AUGUSTA, G A: J. MORRIS, PRINTER AND PUBLISHER. 1858. SOUTHERN MEDICAL KM) SURGICAL JOURNAL. (NEW SERIES.) Vol. XIV.] AUGUSTA, GEORGIA, OCTOBER, 1838. [No. 10. ORIGINAL AXD ECLECTIC. ARTICLE XXII. Observations on Malarial Fever. By Joseph Joxes, A.M., M.D., Professor of Physics and Natural Theology in the University of Georgia, Athens; Professor of Chemistry and Pharmacy in the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta; formerly Professor of Medical Chemistry in the Medical College of Savannah. [Continued from page 601 of September Xo. 1858.] Case XXVIII.—Scotch seaman ; age 14 ; light hair, blue eyes, florid complexion; height 5 feet 2 inches; weight 95 lbs. From light ship, lying at the mouth of Savannah river. Was taken sick three days ago. September 16th, 7 o'clock P. M. Face as red as scarlet; skin in a profuse perspiration, which has saturated his thick flannel shirt and wet the bed-clothes. Pulse 100. Eespiration 24 : does not correspond with the flushed appearance of his face. Tem- perature of atmosphere, 88° F. ; temp, of hand, 102 ; temp, un- der tongue, 103.25. Tip and middle of tongue clean and of a bright red color; posterior portion (root) of tongue, coated with yellow fur; tongue rough and perfectly dry. When the finger is passed over the tongue, it feels as dry and harsh as a rough board. -

2016 General Election Results

Cumulative Report — Official Douglas County, Colorado — 2016 General Election — November 08, 2016 Page 1 of 9 11/22/2016 09:59 AM Total Number of Voters : 192,617 of 241,547 = 79.74% Precincts Reporting 0 of 157 = 0.00% Party Candidate Early Election Total Presidential Electors, Vote For 1 DEM Hillary Clinton / Tim Kaine 68,657 36.62% 0 0.00% 68,657 36.62% REP Donald J. Trump / Michael R. Pence 102,573 54.71% 0 0.00% 102,573 54.71% AMC Darrell L. Castle / Scott N. Bradley 695 0.37% 0 0.00% 695 0.37% LIB Gary Johnson / Bill Weld 10,212 5.45% 0 0.00% 10,212 5.45% GRE Jill Stein / Ajamu Baraka 1,477 0.79% 0 0.00% 1,477 0.79% APV Frank Atwood / Blake Huber 15 0.01% 0 0.00% 15 0.01% AMD "Rocky" Roque De La Fuente / Michael 45 0.02% 0 0.00% 45 0.02% Steinberg PRO James Hedges / Bill Bayes 7 0.00% 0 0.00% 7 0.00% AMR Tom Hoefling / Steve Schulin 37 0.02% 0 0.00% 37 0.02% VOA Chris Keniston / Deacon Taylor 253 0.13% 0 0.00% 253 0.13% SW Alyson Kennedy / Osborne Hart 13 0.01% 0 0.00% 13 0.01% IA Kyle Kenley Kopitke / Nathan R. Sorenson 64 0.03% 0 0.00% 64 0.03% KFP Laurence Kotlikoff / Edward Leamer 29 0.02% 0 0.00% 29 0.02% SAL Gloria Estela La Riva / Dennis J. Banks 10 0.01% 0 0.00% 10 0.01% Bradford Lyttle / Hannah Walsh 13 0.01% 0 0.00% 13 0.01% Joseph Allen Maldonado / Douglas K. -

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

Improving on Nature: Eugenics in Utopian Fiction

1 Improving on Nature: Eugenics in Utopian Fiction Submitted by Christina Jane Lake to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2017 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright materials and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approve for the award of a degree by this or any other university. (Signature)............................................................................................................. 2 3 Abstract There has long been a connection between the concept of utopia as a perfect society and the desire for perfect humans to live in this society. A form of selective breeding takes place in many fictional utopias from Plato’s Republic onwards, but it is only with the naming and promotion of eugenics by Francis Galton in the late nineteenth century that eugenics becomes a consistent and important component of utopian fiction. In my introduction I argue that behind the desire for eugenic fitness within utopias resides a sense that human nature needs improving. Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859) prompted fears of degeneration, and eugenics was seen as a means of restoring purpose and control. Chapter Two examines the impact of Darwin’s ideas on the late nineteenth-century utopia through contrasting the evolutionary fears of Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (1872) with Edward Bellamy’s more positive view of the potential of evolution in Looking Backward (1888). -

003B Alhoff 83

Hist. Phil. Life Sci., 25 (2003), 83-111 ---83 Evolutionary Ethics from Darwin to Moore Fritz Allhoff Department of Philosophy, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA ABSTRACT - Evolutionary ethics has a long history, dating all the way back to Charles Darwin.1 Almost immediately after the publication of the Origin, an immense interest arose in the moral implications of Darwinism and whether the truth of Darwinism would undermine traditional ethics. Though the biological thesis was certainly exciting, nobody suspected that the impact of the Origin would be confined to the scientific arena. As one historian wrote, ‘whether or not ancient populations of armadillos were transformed into the species that currently inhabit the new world was certainly a topic about which zoologists could disagree. But it was in discussing the broader implications of the theory…that tempers flared and statements were made which could transform what otherwise would have been a quiet scholarly meeting into a social scandal’ (Farber 1994, 22). Some resistance to the biological thesis of Darwinism sprung from the thought that it was incompatible with traditional morality and, since one of them had to go, many thought that Darwinism should be rejected. However, some people did realize that a secular ethics was possible so, even if Darwinism did undermine traditional religious beliefs, it need not have any effects on moral thought.2 Before I begin my discussion of evolutionary ethics from Darwin to Moore, I would like to make some more general remarks about its development.3 There are three key events during this history of evolutionary ethics. -

Review of 142 Strand: a Radical Address in Victorian London & George Eliot in Germany,1854-55: 'Cherished Memories'

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The George Eliot Review English, Department of 2007 Review of 142 Strand: A Radical Address in Victorian London & George Eliot in Germany,1854-55: 'Cherished Memories' Rosemary Ashton Gerlinde Roder-Bolton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Ashton, Rosemary and Roder-Bolton, Gerlinde, "Review of 142 Strand: A Radical Address in Victorian London & George Eliot in Germany,1854-55: 'Cherished Memories'" (2007). The George Eliot Review. 522. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger/522 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George Eliot Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Rosemary Ashton, 142 Strand: A RadicalAddress in Victorian London (Chatto & Windus, 2006). pp. xiv + 386. ISBN 0 7011 7370 X Gerlinde Roder-Bolton, George Eliot in Germany,1854-55: 'Cherished Memories' (Ashgate, 2006). pp. xiii + 180. ISBN 0 7546 5054 5 The outlines of Marian Evans's life in the years immediately preceding her emergence as George Eliot are well-known-her work for the Westminster Review, her relationships with Chapman, Spencer and Lewes, and then her departure with the latter to Germany in July 1854. What these two studies do in their different ways is fill in the picture with fascinating detail. In focusing on the house that John Chapman rented from 1847 to 1854 and from which he ran the Westminster Review and his publishing business, Rosemary Ashton recreates the circle of radical intellectuals that the future novelist came into contact with through living there and working as the effective editor of Chapman' s journal. -

Vietnam - Organizations and General Public (Correspondence With)

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 50 Date 30/05/2006 Time 9:35:53 AM S-0871-0004-01-00001 Expanded Number S-0871-0004-01-00001 Title items-in-Peace-keeping operations - Vietnam - organizations and general public (correspondence with) Date Created 02/02/1967 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0871-0004: Peace-Keeping Operations Files of the Secretary-General: U Thant - Viet-Nam Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit <£ " HEARST HEADLINE SERVICE UNITED NATIONS, N. Y. 10O17 O "tit * /.:J' Karai&Bwniliisr UM JCswipwSefil «S& | • Eiifl *.,o tee Mst'5iflTft2c:G .WOK tte iTwfe VLctiira^'i'irt.-iI'M-ii ; haa begua. ta prevail it. elo'iisti docs crmsuit on Hu-jvol OH lies. B &»d M, cluM to t"ne sccre cspreaa tlae iitsp tlsai ell '?-sj:t-£3 to tliu •tici ve feeea svijfc GUS to U^l mR;,v fea rsafiy feT 4r United Ets£K> and tte tTnifsiA Snr'Kie saas Mmo, .possM;/ Easi iLittNjpa, . Aln^'i, -anal ':?;ksvis'ci c5:to nsixtes^ covsn- B»isma, • I if 1I st 1 1 J "Xu-il3il* ' ''*'H' t(- .$A!t.C' •1*. )l«j tV'j i tal'iilcrtV"!*-' i '"il'^l'fU.i.i 01£jf'l ?'•?'"? au£seklSV.tiiatl.fe il.£iS ! '3s sM'un.dscieied. But, ?ifc til' ^"iBfcjaa I'jsS-SKs eca- Esrib^^fSittSa! preaa ^id va-i m-iisi ti, list rrefioti^ ^~K. filGvli^E' at Sis «jEitc&Tia4 caia. ,,' • EOt'srs; b(3£3 esyceb Kmt iftei oj 'GlM-tvff -j." Hi'-ft iiitt KwSti im'J: a s Mr, fefot Istfei? «fefess! o fepefc its & a p^*felt»^ of' 'feists s^ S i»' til® Stli esUM^it of tfe« SA8 a 2» is 8* S* eias* It is a© at l-fes this attsati^it sjssS fbs* as© CITY OF BERKELEY CALIFORNIA VALLACE J.