Housing Discrimination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reslegal V02 1..2

*LRB09317918KEF44175r* HJ0053 LRB093 17918 KEF 44175 r 1 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 2 WHEREAS, The State of Illinois recognizes certain dates of 3 the year for honoring specific patriotic, civic, cultural and 4 historic persons, activities, symbols, or events; and 5 WHEREAS, On June 20, 1782, the American eagle was 6 designated as the National Emblem of the United States when the 7 Great Seal of the United States was adopted, and is the living 8 symbol of the United States' freedoms, spirit and strength; in 9 December 1818, shortly after the Illinois Territory gained 10 statehood, the bald eagle became part of Great Seal of the 11 State of Illinois; and 12 WHEREAS, Found only in North America and once on the 13 endangered species list, the bald eagle population is now 14 growing again, especially along the western border of Illinois; 15 while the natural domain of bald eagles is from Alaska to 16 California, and Maine to Florida, the great State of Illinois 17 provides a winter home for thousands of these majestic birds as 18 they make their journey northwards to the upper Midwest and 19 Canada for spring nesting; and 20 WHEREAS, From December through February, Illinois is home 21 to the largest concentration of wintering bald eagles in the 22 Continental United States; eagle-watching has become a 23 thriving hobby and form of State tourism in at least 27 24 Illinois counties; many organizations and municipalities 25 across the State host annual eagle viewing and educational 26 events and celebrations; and 27 WHEREAS, Illinois is home to -

Ethics in Advertising and Marketing in the Dominican Republic: Interrogating Universal Principles of Truth, Human Dignity, and Corporate Social Responsibility

ETHICS IN ADVERTISING AND MARKETING IN THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: INTERROGATING UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES OF TRUTH, HUMAN DIGNITY, AND CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY BY SALVADOR RAYMUNDO VICTOR DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor William E. Berry, Chair and Director of Research Professor Clifford G. Christians Professor Norman K. Denzin Professor John C. Nerone ABSTRACT This research project has explored and critically examined the intersections between the use of concepts, principles and codes of ethics by advertising practitioners and marketing executives and the standards of practice for mass mediated and integrated marketing communications in the Dominican Republic. A qualitative inquiry approach was considered appropriate for answering the investigation queries. The extensive literature review of the historical media and advertising developments in the country, in conjunction with universal ethics theory, facilitated the structuring of the research questions which addressed the factors affecting the forces that shaped the advertising discourse; the predominant philosophy and moral standard ruling the advertising industry; the ethical guidelines followed by the practitioners; and the compliance with the universal principles of truth, human dignity and social responsibility. A multi- methods research strategy was utilized. In this qualitative inquiry, data were gathered and triangulated using participant observation and in-depth, semi- structured interviews, supplemented by the review of documents and archival records. Twenty industry leaders were interviewed individually in two cities of the country, Santo Domingo and Santiago. These sites account for 98% of the nation-states’ advertising industry. -

Erigenia : Journal of the Southern Illinois Native Plant Society

ERIGENIA THE LIBRARY OF THE DEC IS ba* Number 13 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June 1994 ^:^;-:A-i.,-CS..;.iF/uGN SURVEY Conference Proceedings 26-27 September 1992 Journal of the Eastern Illinois University Illinois Native Plant Society Charleston Erigenia Number 13, June 1994 Editor: Elizabeth L. Shimp, U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Shawnee National Forest, 901 S. Commercial St., Harrisburg, IL 62946 Copy Editor: Floyd A. Swink, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Publications Committee: John E. Ebinger, Botany Department, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL 61920 Ken Konsis, Forest Glen Preserve, R.R. 1 Box 495 A, Westville, IL 61883 Kenneth R. Robertson, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E. Peabody Dr., Champaign, IL 61820 Lawrence R. Stritch, U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Shawnee National Forest, 901 S. Commercial Su, Harrisburg, IL 62946 Cover Design: Christopher J. Whelan, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Cover Illustration: Jean Eglinton, 2202 Hazel Dell Rd., Springfield, IL 62703 Erigenia Artist: Nancy Hart-Stieber, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Executive Committee of the Society - April 1992 to May 1993 President: Kenneth R. Robertson, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E. Peabody Dr., Champaign, IL 61820 President-Elect: J. William Hammel, Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, Springfield, IL 62701 Past President: Jon J. Duerr, Kane County Forest Preserve District, 719 Batavia Ave., Geneva, IL 60134 Treasurer: Mary Susan Moulder, 918 W. Woodlawn, Danville, IL 61832 Recording Secretary: Russell R. Kirt, College of DuPage, Glen EUyn, IL 60137 Corresponding Secretary: John E. Schwegman, Illinois Department of Conservation, Springfield, IL 62701 Membership: Lorna J. Konsis, Forest Glen Preserve, R.R. -

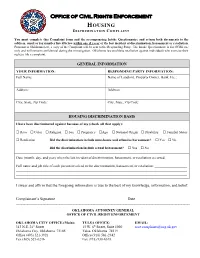

Housing Discrimination Complaint Form

Office of Civil Rights Enforcement HOUSING DISCRIMINATION COMPLAINT You must complete this Complaint form and the accompanying Intake Questionnaire and return both documents to the address, email or fax number listed below within one (1) year of the last incident of discrimination, harassment or retaliation. Pursuant to Oklahoma law, a copy of the Complaint will be sent to the Responding Party. The Intake Questionnaire is for OCRE use only and will remain confidential during the investigation. Oklahoma law prohibits retaliation against individuals who exercise their right to file a complaint. GENERAL INFORMATION YOUR INFORMATION: RESPONDING PARTY INFORMATION: Full Name: Name of Landlord, Property Owner, Bank, Etc.: Address: Address: City, State, Zip Code: City, State, Zip Code: HOUSING DISCRIMINATION BASIS I have been discriminated against because of my (check all that apply): Race Color Religion Sex Pregnancy Age National Origin Disability Familial Status Retaliation Did the discrimination include unwelcome and offensive harassment? Yes No Did the discrimination include sexual harassment? Yes No Date (month, day, and year) when the last incident of discrimination, harassment, or retaliation occurred: ____________ Full name and job title of each person involved in the discrimination, harassment, or retaliation: __________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________ I -

Interview with Dawn Clark Netsch # ISL-A-L-2010-013.07 Interview # 7: September 17, 2010 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Dawn Clark Netsch # ISL-A-L-2010-013.07 Interview # 7: September 17, 2010 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 Note to the Reader: Readers of the oral history memoir should bear in mind that this is a transcript of the spoken word, and that the interviewer, interviewee and editor sought to preserve the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein. We leave these for the reader to judge. DePue: Today is Friday, September 17, 2010 in the afternoon. I’m sitting in an office located in the library at Northwestern University Law School with Senator Dawn Clark Netsch. Good afternoon, Senator. Netsch: Good afternoon. (laughs) DePue: You’ve had a busy day already, haven’t you? Netsch: Wow, yes. (laughs) And there’s more to come. DePue: Why don’t you tell us quickly what you just came from? Netsch: It was not a debate, but it was a forum for the two lieutenant governor candidates sponsored by the group that represents or brings together the association for the people who are in the public relations business. -

Degree Attainment for Black Adults: National and State Trends Authors: Andrew Howard Nichols and J

EDTRUST.ORG Degree Attainment for Black Adults: National and State Trends Authors: Andrew Howard Nichols and J. Oliver Schak Andrew Howard Nichols, Ph.D., is the senior director of higher education research and data analytics and J. Oliver Schak is the senior policy and research associate for higher education at The Education Trust Understanding the economic and social benefits of more college-educated residents, over 40 states during the past decade have set goals to increase their state’s share of adults with college credentials and degrees. In many of these states, achieving these “degree attainment” goals will be directly related to their state’s ability to increase the shares of Black and Latino adults in those states that have college credentials and degrees, particularly as population growth among communities of color continues to outpace the White population and older White workers retire and leave the workforce.1 From 2000 to 2016, for example, the number of Latino adults increased 72 percent and the number of Black adults increased 25 percent, while the number of White adults remained essentially flat. Nationally, there are significant differences in degree attainment among Black, Latino, and White adults, but degree attainment for these groups and the attainment gaps between them vary across states. In this brief, we explore the national trends and state-by-state differences in degree attainment for Black adults, ages 25 to 64 in 41 states.2 We examine degree attainment for Latino adults in a companion brief. National Degree Attainment Trends FIGURE 1 DEGREE ATTAINMENT FOR BLACK AND WHITE ADULTS, 2016 Compared with 47.1 percent of White adults, just 100% 30.8 percent of Black adults have earned some form 7.8% 13.4% 14.0% 30.8% of college degree (i.e., an associate degree or more). -

Read the Transcript

>> I just moved to a new city. I just moved to a new city. And finding a decent place to live was a real challenge. I mean, there are so many hoops to jump through. But just a couple of generations ago, there were even more barriers for someone who looks like me. I didn't see any "whites only" signs at the open house. When I went to sign the contract, the landlord didn't lie to me and tell me the apartment was already rented to someone else. Before President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Bill in 1968, that kind of craziness was totally legal. Landlords could refuse to sell or rent housing because of someone's race, color, religion, sex, family status, national origin, or pretty much any reason. But the Fair Housing Act changed all of that, right? It eliminated housing discrimination, fostered integration, pretty much solved all of our problems. Eh, not so much. So what does that mean for us? What is the impact of housing discrimination today? Let's take a step back. Near the end of the Civil War, General William T. Sherman wanted to set aside land for formerly enslaved families so they weren't starting from scratch. The rallying cry was "40 acres and a mule." But it never happened. Lincoln was assassinated. And Sherman's order was revoked. In spite of this, black communities started to advance. There were black newspapers, black-owned businesses, even black senators within a decade of the end of the Civil War. -

Philosophy and the Black Experience

APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and the Black Experience John McClendon & George Yancy, Co-Editors Spring 2004 Volume 03, Number 2 elaborations on the sage of African American scholarship is by ROM THE DITORS way of centrally investigating the contributions of Amilcar F E Cabral to Marxist philosophical analysis of the African condition. Duran’s “Cabral, African Marxism, and the Notion of History” is a comparative look at Cabral in light of the contributions of We are most happy to announce that this issue of the APA Marxist thinkers C. L. R. James and W. E. B. Du Bois. Duran Newsletter on Philosophy and the Black Experience has several conceptually places Cabral in the role of an innovative fine articles on philosophy of race, philosophy of science (both philosopher within the Marxist tradition of Africana thought. social science and natural science), and political philosophy. Duran highlights Cabral’s profound understanding of the However, before we introduce the articles, we would like to historical development as a manifestation of revolutionary make an announcement on behalf of the Philosophy practice in the African liberation movement. Department at Morgan State University (MSU). It has come to In this issue of the Newsletter, philosopher Gertrude James our attention that MSU may lose the major in philosophy. We Gonzalez de Allen provides a very insightful review of Robert think that the role of our Historically Black Colleges and Birt’s book, The Quest for Community and Identity: Critical Universities and MSU in particular has been of critical Essays in Africana Social Philosophy. significance in attracting African American students to Our last contributor, Dr. -

Housing-Related Hate Activity

Housing-Related Hate Activity National Fair Housing Alliance Agenda • Fair Housing Act’s prohibition against housing-related hate activity • Responding to housing-related hate activity – Forming a response network – Rapid response protocols Fair Housing Act • Title VIII of Civil Rights Act of 1968 • Prohibits discrimination in housing-related transactions because of: –Race – Color – Religion – National origin –Sex – Disability – Familial status (children under age 18 in household) Housing Discrimination • Any attempt to prohibit or limit free and fair housing choice because of a protected class • Applies to all housing-related transactions – Rentals – Real estate sales – Mortgage lending – Appraisals – Homeowners insurance – Zoning Housing-Related Hate Activity • Unlawful to coerce, intimidate, threaten, or interfere with any person in the exercise or enjoyment of fair housing rights, such as: – Renting or buying a house – Reasonable accommodations/modifications – Filing a fair housing complaint • Unlawful to retaliate against someone for exercising fair housing rights – Or for helping another person exercise fair housing rights • 42 U.S.C. § 3617 HUD Regulation • 24 C.F.R. § 100.400 • Unlawful to: – Threaten, intimidate, or interfere with persons in their enjoyment of a dwelling because of their protected class or the protected class of visitors/associates – Intimidate or threaten any person because that person is engaging in activities designed to make other persons aware of, or encouraging such other persons to exercise, fair housing -

SCHOOL DESEGREGATION THROUGH HOUSING INTEGRATION INCENTIVES Adopted by Convention Delegates May 5, 1982 Reviewed by Board of Managers March 2012

71 SCHOOL DESEGREGATION THROUGH HOUSING INTEGRATION INCENTIVES Adopted by Convention Delegates May 5, 1982 Reviewed by Board of Managers March 2012 WHEREAS, Racial segregation in housing has contributed to segregation in public schools in California; and WHEREAS, Action to discriminate or segregate on the basis of race in either housing or education is in violation of California law; and WHEREAS, Officials in both education and housing have legal responsibilities to take positive actions to desegregate; and WHEREAS, Discrimination and segregation in either public schools or in housing make desegregation efforts more difficult and costly; and WHEREAS, Desegregation of neighborhood housing could contribute constructively to school desegregation; and WHEREAS, School desegregation programs will continue to involve substantial costs permanently unless desegregation of neighborhood housing is achieved; and WHEREAS, Such desegregation could make possible naturally integrated neighborhood schools and enhancement of intergroup education; and WHEREAS, Both the National and State PTAs are on record favoring equal opportunity in both housing and education; now therefore be it RESOLVED, That the California State PTA seek and support legislation to provide incentives for desegregation of neighborhood housing; and be it further RESOLVED, That the California State PTA urge its units, councils and districts to serve as unifying forces in achieving desegregation of both housing and schools; and be it further RESOLVED, That the California State PTA urge -

Basic Issues of the Illinois Territory (1809-1818)

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects History Department 1961 Basic Issues of the Illinois Territory (1809-1818) Jack F. Kinton '61 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Kinton '61, Jack F., "Basic Issues of the Illinois Territory (1809-1818)" (1961). Honors Projects. 43. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj/43 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Ie IS TJll1RITORY (1809-1818) SPECIAL COLLECTiONS F by Jack 1961 1 Introduction '�'WIn:ts . paper 1:1aS VJ:t"1.tten_ to n:rov::..••de :1.nS:1r;ht• as area t S history helps explain i.tihy certain things are the vlay they are today in the area. as importmlt a1.�e the influences of OLe area 011 other areas. The influences on an area by other areas just as the area's influence on other ;u:eas are too numerous and weighty to deal 1:Jith corq;lctcly. -

Petitioners, V

No. 20- IN THE Supreme Court of the United States MARIA PAppAS, TREASURER AND EX-OFFICIO COLLEctOR OF COOK COUntY, ILLINOIS AND THE COUntY OF COOK, Petitioners, v. A.F. MOORE & ASSOCIATES, Inc., J. EmIL AnDERSON & SON, Inc., PRIME GROUP REALTY TRUST, AmERICAN AcADEMY OF ORTHOPAEDIC SURGEONS, ERLIng EIDE, FOX VALLEY/RIVER OAKS PARTNERSHIP, SIMON PROPERTY GROUP, INC. AND FRITZ KAEGI, ASSESSOR OF COOK COUNTY, Respondents. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES CouRT OF AppEALS FOR THE SEVENTH CIRcuIT PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI CATHY MCNEIL STEIN KIMBERLY M. FOXX AssisTANT STATE’S ATTORNEY COOK COUNTY STATE’S ATTORNEY CHIEF, CIVIL ACTIONS BUREAU 500 Richard J. Daley Center Chicago, Illinois 60602 PAUL A. CASTIGLIONE* (312) 603-2350 ANTHONY M. O’BRIEN [email protected] AssisTANT STATE’S ATTORNEYS Of Counsel Counsel for Petitioners * Counsel of Record 297284 A (800) 274-3321 • (800) 359-6859 i QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether the Equal Protection Clause mandates that a real estate taxpayer seeking a refund based on an over assessment of real property be able to challenge the methodology that the assessing official used and to conduct discovery on such assessment methodology, where that methodology is not probative to the refund claim that State law provides and where State law provides a complete and adequate remedy in which all objections to taxes may be raised. 2. Whether the decision below improperly held that the Tax Injunction Act and the comity doctrine did not bar federal jurisdiction over Respondents’