The Promises and Pitfalls of Postcolonial Theory and Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samir Gandesha1 the Aesthetic Politics of Hegemony

Studi di estetica, anno XLVI, IV serie, 3/2018 ISSN 0585-4733, ISSN digitale 1825-8646, DOI 10.7413/18258646066 Samir Gandesha1 The aesthetic politics of hegemony Abstract In this article, it is argued that Gramsci’s conception of hegemony ought to be located not simply in the theory and praxis of Leninism but also in Gramsci’s read- ing of Machiavelli. By situating such a reading in relation to Nietzsche’s notion of will to power, it is possible to defend Gramsci’s political theory against some of the criticisms leveled by those who decry the “hegemony of hegemony”. Such a reading of the concept of hegemony enables us to understand the idea of “com- mon sense” as oriented towards the distribution and redistribution of the sensible. Keywords Aesthetics, Gramsci, Hegemony 1. Introduction In the introduction to our book Aesthetic Marx (2017), Johan Hartle and I point out that there is one main problem with the Marxological approach to the aesthetic dimensions of Marx’s writings: the classical understanding of the discipline of aesthetics that is presupposed by such exegetical approaches must also be interrogated. “Aesthetics” is normally understood as a philosophical discipline that concerns the conditions for the possibility of judgments of taste, as a specific ra- tionality that maintains its own autonomy, its own purposeless pur- posiveness, against contending and competing the spheres of value (the epistemic, the moral), and that deals with normative criteria in order to evaluate forms of experience and artistic developments on 1 [email protected]. I would like to thank professor Stefano Marino for his extremely helpful suggestions and assistance with this article. -

History, Postcolonialism and Postmodernism in Toni Morrison's

History, Postcolonialism and Postmodernism in Toni Morrison’s Beloved Mariangela Palladino This paper examines Toni Morrison’s fifth novel, Beloved, which, together with Jazz and Paradise, constitute Morrison’s contribution to the process of re-writing black American history. Postcolonial thought has offered one of the most potent challenges to the notion of the ‘end of history’ posited by postmodernists of both left and right. Focusing principally on Beloved (1987), my paper explores how Toni Morrison insists upon the necessity of a conscious and inevitably painful engagement with the past. Uncovering a dense series of correspondences, drawing upon Christological symbols, nu- merology, and flower imagery, I argue that the principal character is closely identified with Christ throughout the novel, which in its final part refigures the Passion narrative. As a sacrificed black, female Christ, Beloved becomes a focus for Morrison’s concern with redemption through memory. I wish to briefly explore the debate on history between postmodernism and postcolonialism as it constitutes the framework to Toni Morrison’s de- ployment of Christological imagery in order to engage with history. If the dawn of postmodernism marked the beginning of a ‘posthistoric’ era which ‘stipulated that the segment of human life had ended for which history had claimed to offer explanation and understanding’ (Breisach 2003 10), this has been uncompromisingly contested by postcolonialism. The postcolonial claim for the unacknowledged role of the non-Western world in the constitu- tion of modernity is emphasized by Edward Said in Culture and Imperialism (1993) as follows: In the West, post-modernism has seized upon the ahistorical weightlessness, consumerism, and spectacle of the new order. -

Edward Said: the Postcolonial Theory and the Literature of Decolonization

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal June 2014 /SPECIAL/ edition vol.2 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 EDWARD SAID: THE POSTCOLONIAL THEORY AND THE LITERATURE OF DECOLONIZATION Lutfi Hamadi, PhD Lebanese International University, Lebanon Abstract This paper attempts an exploration of the literary theory of postcolonialism, which traces European colonialism of many regions all over the world, its effects on various aspects of the lives of the colonized people and its manifestations in the Western literary and philosophical heritage. Shedding light on the impact of this theory in the field of literary criticism, the paper focuses on Edward Said's views for the simple reason that he is considered the one who laid the cornerstone of this theory, despite the undeniable role of other leading figures. This theory is mainly based on what Said considers the false image of the Orient fabricated by Western thinkers as the primitive "other" in contrast with the civilized West. He believes that the consequences of colonialism are still persisting in the form of chaos, coups, corruption, civil wars, and bloodshed, which permeates many ex-colonies. The powerful colonizer has imposed a language and a culture, whereas those of the Oriental peoples have been ignored or distorted. Referring to some works of colonial and postcolonial novelists, the paper shows how being free from the repression of imperialism, the natives could, eventually, produce their own culture of opposition, build their own image, and write their history outside the frame they have for long been put into. -

History 594: Methods and Theory in the Historical Study of Religion (Women, War, and Religion in Early Medieval Europe) Dr

History 594: Methods and Theory in the Historical Study of Religion (Women, War, and Religion in Early Medieval Europe) Dr. Katherine E. Milco FALL 2020 ONLINE COURSE on Canvas Email: [email protected] Course Description: This course focuses on the topics of women, war, and religion in late antiquity and early medieval Europe. The emphasis is placed on the critical analysis of ancient texts, which is the essence of historical methodology that professional historians use today. The final third of the course will examine and evaluate different contemporary methodologies – postmodernism, Marxism, feminism, psychohistory, postcolonialism – that some professional historians use in the study of history. Course Objectives: 1. To learn how to use and analyze primary sources. 2. To learn the role of secondary sources in historical research: positive and negative. 3. To understand and utilize contemporary methodologies utilized in the discipline of history. Required Textbook: There is no required textbook for you to purchase. All readings will be provided to you free of charge via Canvas. Grading Scale: 95-100 A 80-82 B- 67-69 D+ 90-94 A- 77-79 C+ 63-66 D 87-89 B+ 73-76 C 60-62 D- 83-86 B 70-72 C- Lower than 60 F Evaluation: Reading Responses 80% Final Paper 20% Course Components: 1. Reading Responses: There are a total of 18 reading responses assigned over the course of the semester. These are responses that you give to questions that I pose about the text. For the first 7 weeks of the course, all the reading responses will answer questions that I pose about ancient source material. -

Fall 2005 Newsletter of the ASA Comparative and Historical Sociology Section Volume 17, No

________________________________________________________________________ __ Comparative & Historical Sociology Fall 2005 Newsletter of the ASA Comparative and Historical Sociology section Volume 17, No. 1 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ From the Chair: State of the CHS Union SECTION OFFICERS 2005-2006 Richard Lachmann SUNY-Albany Chair Richard Lachmann Columns of this sort are the academic equivalents of State SUNY-Albany of the Union speeches, opportunities to say that all is well and to take credit for the good times. Chair-Elect William Roy I can’t (and won’t) take credit for the healthy state of com- University of California-Los Angeles parative historical sociology but I do want to encourage all of us to recognize the richness of our theoretical discus- sions and the breadth and depth of our empirical work. The Past Chair Jeff Goodwin mid-twentieth century revolution in historiography—the New York University discovery and creative interpretation of previously ignored sources, many created by historical actors whose agency had been slighted and misunderstood—has been succeeded Secretary-Treasurer by the recent flowering of comparative historical work by Genevieve Zubrzycki sociologists. University of Michigan We can see the ambition and reach of our colleagues’ work Council Members in the research presented at our section’s panels in Phila- Miguel A. Centeno, Princeton (2007) delphia and in the plans for sessions next year (see the call Rebecca Jean Emigh, UCLA (2006) for papers elsewhere in this newsletter). The Author Meets Marion Fourade-Gourinchas, Berkeley (2008) Critics panel on Julia Adams, Lis Clemens, and Ann Or- Fatma Muge Gocek, U Michigan (2006) Mara Loveman, UW-Madison (2008) loff’s Remaking Modernity: Politics, History, and Sociol- James Mahoney, Northwestern (2007) ogy was emblematic of how our field’s progress got ex- pressed at the Annual Meeting. -

Colonialism Postcolonialism

SECOND EDITION Colonialism/Postcolonialism is both a crystal-clear and authoritative introduction to the field and a cogently-argued defence of the field’s radical potential. It’s exactly the sort of book teachers want their stu- dents to read. Peter Hulme, Department of Literature, Film and Theatre Studies, University of Essex Loomba is a keen and canny critic of ever-shifting geopolitical reali- ties, and Colonialism/Postcolonialism remains a primer for the aca- demic and common reader alike. Antoinette Burton, Department of History, University of Illinois It is rare to come across a book that can engage both student and specialist. Loomba simultaneously maps a field and contributes provocatively to key debates within it. Situated comparatively across disciplines and cultural contexts, this book is essential reading for anyone with an interest in postcolonial studies. Priyamvada Gopal, Faculty of English, Cambridge University Colonialism/Postcolonialism moves adroitly between the general and the particular, the conceptual and the contextual, the local and the global, and between texts and material processes. Distrustful of established and self-perpetuating assumptions, foci and canonical texts which threaten to fossilize postcolonial studies as a discipline, Loomba’s magisterial study raises many crucial issues pertaining to social structure and identity; engaging with different modes of theory and social explanation in the process. There is no doubt that this book remains the best general introduction to the field. Kelwyn Sole, English Department, University of Cape Town Lucid and incisive this is a wonderful introduction to the contentious yet vibrant field of post-colonial studies. With consummate ease Loomba maps the field, unravels the many strands of the debate and provides a considered critique. -

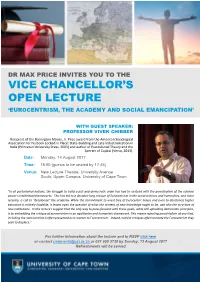

Vice Chancellor's Open Lecture

DR MAX PRICE INVITES YOU TO THE VICE CHANCELLOR’S OPEN LECTURE ‘EUROCENTRISM, THE ACADEMY AND SOCIAL EMANCIPATION’ WITH GUEST SPEAKER: PROFESSOR VIVEK CHIBBER Recipient of the Barrington Moore, Jr. Prize award from the American Sociological Association for his book Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India (Princeton University Press, 2003) and author of Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital (Verso, 2013). Date: Monday, 14 August 2017 Time: 18:00 (guests to be seated by 17:45) Venue: New Lecture Theatre, University Avenue South, Upper Campus, University of Cape Town "In all postcolonial nations, the struggle to build a just and democratic order has had to contend with the parochialism of the colonial power’s intellectual frameworks. This has led to a decades-long critique of Eurocentrism in the social sciences and humanities, and more recently, a call to “decolonize” the academy. While the commitment to wrest free of Eurocentric biases and even to decolonize higher education is entirely laudable, it leaves open the question of what the content of new knowledge ought to be, and also the structure of new institutions. In this lecture I suggest that the only way to press forward with these goals, while still upholding democratic principles, is by embedding the critique of eurocentrism in an egalitarian and humanistic framework. This means rejecting parochialism of any kind, including the nativism that is often presented as a counter to Eurocentrism. Indeed, nativist critiques often recreate the Eurocentrism they seek to displace." For further information about the lecture and to RSVP click here or contact [email protected] or 021 650 3730 by Sunday, 13 August 2017 Refreshments will be served . -

Postcolonialism

10 Postcolonialism The final hour of colonialism has struck, and millions of inhabitants of Africa, Asia, and Latin America rise to meet a new life and demand their unrestricted right to self-determination. Che Guevara, speech to the United Nations, December 11, 1964 he 1960s saw a revolutionary change in literary theory. Until this dec- Tade, New Criticism dominated literary theory and criticism, with its insistence that “the” one correct interpretation of a text could be discovered if critical readers follow the prescribed methodology asserted by the New Critics. Positing an autonomous text, New Critics paid little attention to a text’s historical context or to the feelings, beliefs, and ideas of a text’s read- ers. For New Critics, a text’s meaning is inextricably bound to ambiguity, irony, and paradox found within the structure of the text itself. By analyzing the text alone, New Critics believe that an astute critic can identify a text’s central paradox and explain how the text ultimately resolves that paradox while also supporting the text’s overarching theme. Into this seemingly self-assured system of hermeneutics marches philos- opher and literary critic Jacques Derrida along with similar-thinking scholar- critics in the late 1960s. Unlike the New Critics, Derrida, the chief spokesperson for deconstruction, disputes a text’s objective existence. Denying that a text is an autotelic artifact, he challenges the accepted definitions and assump- tions of both the reading and the writing processes. In addition, he insists on questioning what parts not only the text but also the reader and the author play in the interpretive process. -

Decolonizing Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political Economy: Transmodernity, Decolonial Thinking, and Global Coloniality

Decolonizing Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political Economy: Transmodernity, Decolonial Thinking, and Global Coloniality RAMÓN GROSFOGUEL UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Can we produce a radical anti-systemic politics beyond identity politics? Is it possible to articulate a critical cosmopolitanism beyond nationalism and colonialism? Can we produce knowledges beyond Third World and Eurocentric fundamentalisms? Can we overcome the traditional dichotomy between political-economy and cultural studies? Can we move beyond economic reductionism and culturalism? How can we overcome the Eurocentric modernity without throwing away the best of modernity as many Third World fundamentalists do? In this paper, I propose that an epistemic perspective from the subaltern side of the colonial difference has a lot to contribute to this debate. It can contribute to a critical perspective beyond the outlined dichotomies and to a redefinition of capitalism as a world-system. In October 1998, there was a conference/dialogue at Duke University between the South Asian Subaltern Studies Group and the Latin American Subaltern Studies Group. The dialogue initiated at this conference eventually resulted in the publication of several issues of the journal NEPANTLA. However, this conference was the last time the Latin American Subaltern Studies Group met before their split. Among the many reasons and debates that produced this split, there are two that I would like to stress. The members of the Latin American Subaltern Studies Group were primarily Latinamericanist scholars in the USA. Despite their attempt at producing a radical and alternative knowledge, they reproduced the epistemic schema of Area Studies in the United States. With a few exceptions, they produced studies about the subaltern rather than studies with and from a subaltern perspective. -

Postcolonialism Rahul Rao

Postcolonialism Rahul Rao [Forthcoming in The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies, eds. Michael Freeden, Marc Stears, Lyman Tower Sargent (Oxford University Press, 2012)] Writing in 1992 about the ‘pitfalls of the term “post-colonialism”’, Anne McClintock places it in the cacophonous company of other ‘post’ words in the culture of the time—‘post-colonialism, post-modernism, post-structuralism, post-cold war, post- marxism, post-apartheid, post-Soviet, post-Ford, post-feminism, post-national, post- historic, even post-contemporary’—the enthusiasm for which she reads as a symptom of ‘a global crisis in ideologies of the future, particularly in the ideology of “progress”’ (McClintock 1992: 93). The collapse of both capitalist and communist teleologies of development in the debt-wracked Third World seemed to conspire with postmodernist critiques of metanarrative to discredit not only particular articulations of ‘progress’ but also the very enterprise of charting a ‘progressive’ politics. Setting themselves resolutely against a past that they are determined to transcend, ‘post’ words drift in a present that seems allergic to thinking about the future. Writing in 2004 and looking back on nearly three decades of ‘postcolonial studies’ in the academy, Neil Lazarus traces a significant shift in the meaning of the term ‘postcolonial’. Originally used in a strictly temporal sense to refer to the period immediately after decolonization (‘post’ as ‘after’), Lazarus cites a markedly different usage in the work of Homi Bhabha for whom ‘“postcolonial” is a fighting term’, invoked in polemics against colonialism but also against anti-colonial discourses such as Marxism and nationalism that are disavowed on account of their essentialism and deconstructed in the vocabulary of poststructuralism (Lazarus 2004: 4). -

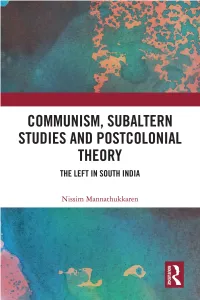

Communism, Subaltern Studies and Postcolonial Theory

COMMUNISM, SUBALTERN STUDIES AND POSTCOLONIAL THEORY This book is a thematic history of the communist movement in Kerala, the first major region (in terms of population) in the world to democratically elect a communist government. It analyzes the nature of the transformation brought about by the communist movement in Kerala, and what its implications could be for other postcolonial societies. The volume engages with the key theoretical concepts in postcolonial theory and Subaltern Studies, and contributes to the debate between Marxism and postcolonial theory, especially its recent articulations. The volume presents a fresh empirical engagement with theoretical critiques of Subaltern Studies and postcolonial theory, in the context of their decades-long scholarship in India. It discusses important thematic moments in Kerala’s communist history which include—the processes by which it established its hegemony, its cultural interventions, the institution of land reforms and workers’ rights, and the democratic decentralization project, and, ultimately, communism’s incomplete national-popular and its massive failures with regard to the caste question. A significant contribution to scholarship on democracy and modernity in the Global South, this volume will be of great interest to scholars and researchers of politics, specifically political theory, democracy and political participation, political sociology, development studies, postcolonial theory, Subaltern Studies, Global South Studies and South Asia Studies. Nissim Mannathukkaren is Associate Professor in the International Development Studies Department at Dalhousie University, Canada. He is the author of the book The Rupture with Memory: Derrida and the Specters That Haunt Marxism (2006). His research has been published in journals such as Citizenship Studies, Journal of Peasant Studies, Third World Quarterly, Economic and Political Weekly, Journal of Critical Realism, International Journal of the History of Sport, Dialectical Anthropology, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies and Sikh Formations. -

SOCIOLOGY 9191A Social Science in the Marxian Tradition Fall 2020

SOCIOLOGY 9191A Social Science in the Marxian Tradition Fall 2020 DRAFT Class times and location Wednesday 10:30am -12:30pm Virtual synchronous Instructor: David Calnitsky Office Hours by appointment Department of Sociology Office: SSC 5402 Email: [email protected] Technical Requirements: Stable internet connection Laptop or computer Working microphone Working webcam “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.” – Karl Marx That is the point, it’s true—but not in this course. This quote, indirectly, hints at a deep tension in Marxism. If we want to change the world we need to understand it. But the desire to change something can infect our understanding of it. This is a pervasive dynamic in the history of Marxism and the first step is to admit there is a problem. This means acknowledging the presence of wishful thinking, without letting it induce paralysis. On the other hand, if there are pitfalls in being upfront in your desire to change the world there are also virtues. The normative 1 goal of social change helps to avoid common trappings of academia, in particular, the laser focus on irrelevant questions. Plus, in having a set of value commitments, stated clearly, you avoid the false pretense that values don’t enter in the backdoor in social science, which they often do if you’re paying attention. With this caveat in place, Marxian social science really does have a lot to offer in understanding the world and that’s what we’ll analyze in this course. The goal is to look at the different hypotheses that broadly emerge out of the Marxian tradition and see the extent to which they can be supported both theoretically and empirically.