Appendix 1 Tees Valley Bus Service Delivery Options Technical Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUS SERVICES (WALES) BILL Explanatory Memorandum

BUS SERVICES (WALES) BILL Explanatory Memorandum incorporating the Regulatory Impact Assessment and Explanatory Notes March 2020 Bus Services (Wales) Bill Explanatory Memorandum to Bus Services (Wales) Bill This Explanatory Memorandum has been prepared by Department of Economy, Skills and Natural Resources of the Welsh Government and is laid before the National Assembly for Wales. Member’s Declaration In my view the provisions of the Bus Services (Wales) Bill, introduced by me on the 16 March 2020, would be within the legislative competence of the National Assembly for Wales. Ken Skates AM Minister for Economy and Transport Assembly Member in charge of the Bill 16 March 2020 1 Contents page Part 1 – EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM 1. Description 2. Legislative Competence 3. Purpose and intended effect of the legislation 4. Consultation 5. Power to make subordinate legislation PART 2 – REGULATORY IMPACT ASSESSMENT 6. Regulatory Impact Assessment summary 7. Options 8. Costs and benefits 9. Impact Assessments 10. Post implementation review ANNEX 1 – Explanatory Notes ANNEX 2 – Index of Standing Orders ANNEX 3 – Schedule of Amendments 2 PART 1 – EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM 1. Chapter 1 – Description 1.1 The Bus Service (Wales) Bill will make changes to the legislative framework relating to the planning and delivery of local bus services in Wales. It will amend the existing legislative provision and provide local authorities with an improved range of tools to consider using when planning and delivering local bus services. The Bill will put in place new information sharing arrangements. 3 2. Chapter 2 – Legislative Competence 2.1 The National Assembly for Wales (‘the Assembly") has the legislative competence to make the provisions in the Bus Services (Wales) Bill (“the Bill”) pursuant to Part 4 of the Government of Wales Act 2006 ("GoWA 2006") as amended by the Wales Act 2017. -

Advanced Urban Transit Technologies Market Testing Final Report

Advanced Urban Transit Technologies – Worldwide Market Testing Report summarising the feedback received through the Market Testing March 2020 £69.6 Billion GVA A region packed with ambition and untapped potential In partnership with: Institute for Transport Studies Table of Contents 1. PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT ................................................................................................................................. 4 Who is undertaking the Market Testing? .................................................................................................................. 5 What Happens Next? ................................................................................................................................................ 5 2. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT ........................................................................................................................... 6 This report ................................................................................................................................................................. 7 3. SUMMARY OF KEY MESSAGES ........................................................................................................................... 8 4. FEEDBACK ON DISCUSSION AREA 1A ................................................................................................................12 Illustrative Quotes from Respondents ..................................................................................................................... 12 Points raised -

The Road to Zero Next Steps Towards Cleaner Road Transport and Delivering Our Industrial Strategy

The Road to Zero Next steps towards cleaner road transport and delivering our Industrial Strategy July 2018 The Road to Zero Next steps towards cleaner road transport and delivering our Industrial Strategy The Government has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the Government’s website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact the Department. Department for Transport Great Minster House 33 Horseferry Road London SW1P 4DR Telephone 0300 330 3000 General enquiries https://forms.dft.gov.uk Website www.gov.uk/dft © Crown copyright, 2018, except where otherwise stated. Printed in July 2018. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos or third-party material) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v2.0. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Contents Foreword 1 Policies at a glance 2 Executive Summary 7 Part 1: Drivers of change 21 Part 2: Vehicle Supply and Demand 33 Part 2a: Reducing emissions from vehicles already on our roads 34 Part 2b: Driving uptake of the cleanest new cars and vans 42 Part 2c: -

The Public Service Vehicles (Open Data) (England) Regulations 2020 No

Draft Legislation: This is a draft item of legislation. This draft has since been made as a UK Statutory Instrument: The Public Service Vehicles (Open Data) (England) Regulations 2020 No. 749 Draft Regulations laid before Parliament under section 160(2A) of the Transport Act 2000, for approval by resolution of each House of Parliament. DRAFT STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2020 No.0000 PUBLIC PASSENGER TRANSPORT, ENGLAND The Public Service Vehicles (Open Data) (England) Regulations 2020 Made - - - - 2020 Coming into force in accordance with regulation 1 The Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred by section 141A of the Transport Act 2000(1), makes the following Regulations. The Secretary of State has, in accordance with section 141A(10) of the Transport Act 2000, consulted such persons and organisations appearing to him to represent the interests of operators and users of relevant local services, such persons and organisations appearing to him to represent the interests of local transport authorities whose areas are in England, and such other persons and organisations as he considered appropriate. A draft of this instrument has been laid before, and approved by a resolution of, each House of Parliament pursuant to section 160(2A) of the Transport Act 2000(2). Citation and commencement 1.—(1) These Regulations may be cited as the Public Service Vehicles (Open Data) (England) Regulations 2020. (2) These Regulations come into force twenty-one days after the day on which they are made. Interpretation 2.—(1) In these Regulations— “the 1986 Regulations” means the Public Service Vehicles (Registration of Local Services) Regulations 1986(3); (1) 2000 c.38. -

Delivering Change Improving Urban Bus Services

Delivering change Improving urban bus services Simon Jeffrey November 2019 About Centre for Cities Centre for Cities is a research and policy institute, dedicated to improving the economic success of UK cities. We are a charity that works with cities, business and Whitehall to develop and implement policy that supports the performance of urban economies. We do this through impartial research and knowledge exchange. For more information, please visit www.centreforcities.org/about Partnerships Centre for Cities is always keen to work in partnership with like-minded organisations who share our commitment to helping cities to thrive, and supporting policy makers to achieve that aim. As a registered charity (no. 1119841) we rely on external support to deliver our programme of quality research and events. To find out more please visit: www.centreforcities.org/about/partnerships About the author Simon Jeffrey is a policy officer at Centre for Cities: [email protected] | 020 7803 4321 About the sponsor This report was supported by Abellio, Metroline and Tower Transit. Delivering change • Improving urban bus services • November 2019 00 Executive summary Buses are critical urban infrastructure. They not only provide access to jobs for workers without a car, but they offer the mass-transit capacity that make jobs-dense, high-wage city centre economies possible. In so doing they take cars off of the road, and reduce greenhouse gases, nitrogen dioxides and fine particulate matter from tyres and brakes. Bus services link people to friends and family, young people to education, shoppers to high streets and communities to the public services — from GPs’ surgeries to libraries — that they need. -

Stagecoach Group Annual Report and Financial Statements 2021 Strategic and Operational Highlights

and 2021 Financial Statements Stagecoach Group Annual Report Group Stagecoach Stagecoach Group Annual Report and Financial Statements 2021 Strategic and operational highlights • Continuing delivery of our immediate priorities • Protecting and promoting the health and wellbeing of our colleagues and customers • Partnership working with government and local authorities to deliver critical public transport • Continuing work with government to drive, and financially support, a recovery in bus patronage • Protecting the long-term sustainability of our business • Actions underway to leverage potential from new transformational government bus strategy for England • Significant opportunities for modal shift from car through new partnership structures, local bus service improvement plans and more bus priority measures • New sustainability strategy and continued strong environmental performance • New long-term sustainability strategy finalised, with zero emissions UK bus fleet targeted by 2035 • Key partner in UK’s first All Electric Bus City in Coventry • London Stock Exchange Green Economy Mark and MSCI ESG “A” rating reaffirmed • FTSE4Good 97th (2020: 98th) percentile ranking and “low risk” rating from Sustainalytics maintained • Further progress on delivery of business strategy • Protecting the business through robust cost control and planning for recovery • Progressing partnership opportunities and new commercial initiatives in the UK, as well as bids for overseas contracts • Positive trends in regional bus • Vehicle mileage now restored to -

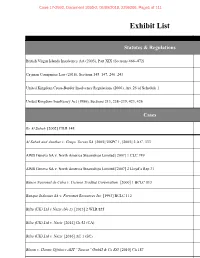

Exhibit List

Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page1 of 111 Exhibit List Statutes & Regulations British Virgin Islands Insolvency Act (2003), Part XIX (Sections 466–472) B Cayman Companies Law (2016), Sections 145–147, 240–243 United Kingdom Cross-Border Insolvency Regulations (2006), Art. 25 of Schedule 1 United Kingdom Insolvency Act (1986), Sections 213, 238–239, 423, 426 Cases Re Al Sabah [2002] CILR 148 Al Sabah and Another v. Grupo Torras SA [2005] UKPC 1, [2005] 2 A.C. 333 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 1 CLC 749 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 31 Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Cosmos Trading Corporation [2000] 1 BCLC 813 Banque Indosuez SA v. Ferromet Resources Inc [1993] BCLC 112 Bilta (UK) Ltd v Nazir (No 2) [2013] 2 WLR 825 Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2014] Ch 52 (CA) Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2016] AC 1 (SC) Bloom v. Harms Offshore AHT “Taurus” GmbH & Co KG [2010] Ch 187 Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page2 of 111 Exhibit List Cases, continued Re Paramount Airways Ltd [1993] Ch 223 Picard v. Bernard L Madoff Investment Securities LLC BVIHCV140/2010 B Rubin v. Eurofinance SA [2013] 1 AC 236; [2012] UKSC 46 Singularis Holdings Ltd v. PricewaterhouseCoopers [2014] UKPC 36, [2015] A.C. 1675 Stichting Shell Pensioenfonds v. Krys [2015] AC 616; [2014] UKPC 41 Other Authorities McPherson’s Law of Company Liquidation (4th ed. 2017) Anthony Smellie, A Cayman Islands Perspective on Trans-Border Insolvencies and Bankruptcies: The Case for Judicial Co-Operation , 2 Beijing L. -

Bus Services Act 2017 Noel Dempsey

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 7545, 16 August 2018 By Louise Butcher Bus Services Act 2017 Noel Dempsey Inside: 1. The English bus market 2. How did we get here? 3. Deregulation: the debate 4. The Act 5. Regulations and guidance 6. Local implementation www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number CBP 7545, 16 August 2018 2 Contents Summary 3 1. The English bus market 4 1.1 Patronage 5 1.2 Fares 6 1.3 Funding 7 1.4 Satisfaction 8 1.5 Operators 8 1.6 Local transport authorities 9 1.7 Traffic Commissioners 10 1.8 London 11 2. How did we get here? 12 2.1 Brief history of the post-war bus market 12 2.2 Deregulation in the 1980s 13 London 14 2.3 Labour Government: Quality Partnerships and Contracts 16 Quality Contract Schemes 17 Partnership schemes 18 2.4 Conservative-led governments: fiscal consolidation and devolution 19 Cuts to subsidised services 20 The drive to devolution 21 3. Deregulation: the debate 23 3.1 Successes 23 3.2 Failures 24 3.3 Would regulation improve services and cut costs? 26 4. The Act 29 4.1 Background and workshops, 2015 29 4.2 Reaction 30 4.3 Advanced Quality Partnerships (AQPs) 31 4.4 Franchising 31 4.5 Ticketing 34 4.6 Enhanced Partnerships 35 4.7 Information for bus passengers 36 4.8 Information about English bus services 36 4.9 Ban on new municipal bus companies 37 4.10 Other sections 38 5. Regulations and guidance 40 5.1 AQP regulations 40 5.2 Franchising regulations 40 5.3 EP regulations 41 5.4 Pensions and TUPE regulations for franchising and EPs 42 5.5 Information regulations 43 5.6 Statutory guidance 45 6. -

Strategies for Joint Procurement of Fuel Cell Buses Final Report

Strategies for joint procurement of fuel cell buses Final report Strategies for joint procurement of fuel cell buses A study for the Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Joint Undertaking 1 © FCH JU, 2018 Catalogue number: EG-01-18-508-EN-N ISBN: 978-92-9246-325-0 DOI: 10.2843/459429 Date of publication: 2018 Strategies for joint procurement of fuel cell buses Final report Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Joint Study sponsor Undertaking (FCH JU) Lead author Element Energy Limited Other contributors EE ENERGY ENGINEERS GmbH hySOLUTIONS GmbH RebelGroup Advisory BV Twynstra Gudde Mobiliteit en Infrastructuur BV Association Française pour l’Hydrogène et let Piles à Combustible The Latvian Academy of Sciences Contact Michael Dolman: [email protected] Ben Madden: [email protected] Disclaimer This study has been prepared for general guidance only. The reader should not act on any information provided in this study without receiving appropriate professional advice. The information and views set out in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. Element Energy Limited shall not be liable for any damages resulting from the use of information contained in the study. Confidential – not for publication Strategies for joint procurement of fuel cell buses Final report Contents 1 Executive summary ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Context ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Highlights and conclusions ....................................................................................... 2 1.3 Next steps................................................................................................................ -

Westminsterresearch Prospects in Britain in the Light of the Bus Services Act 2017 White, P

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Prospects in Britain in the light of the Bus Services Act 2017 White, P. This is an accepted manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Research in Transportation Economics, 69, pp. 337-343. The final definitive version is available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2018.03.003 © 2018 Taylor & Francis The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Prospects in Britain in the light of the Bus Services Act 1. Historical background 1.1 The express coach experience Under the Transport Act of 1980, express coach services in Britain were ‘deregulated’, removing controls on pricing, capacity and route licensing, although quality controls on operators were strengthened. The outcomes were generally regarded as successful in terms of stimulating ridership, lower fares and service innovations. Subsequent changes in other European countries such as Norway, Sweden, France and Germany can be seen as implementing similar policies, also with positive outcomes. A review of the British case is provided by White and Robbins (2012). It is noteworthy, however, that despite apparent ease of entry by smaller operators, the main competition is inter-modal (with rail and car), and clearly dominant operators have emerged within the coach sector. -

Transport (Scotland) Bill: Buses

SPICe Briefing Pàipear-ullachaidh SPICe Transport (Scotland) Bill: Buses Alan Rehfisch This briefing provides an overview of bus service regulation in Scotland and sets out how this regulatory regime would be amended by the proposals in the Transport (Scotland) Bill. 3 September 2018 SB 18-54 Transport (Scotland) Bill: Buses, SB 18-54 Contents Executive Summary _____________________________________________________3 Introduction ____________________________________________________________4 The current regulatory regime for local bus services in Scotland ________________5 Who provides Scottish local bus services? ___________________________________5 Who funds Scottish local bus services?______________________________________5 Who regulates Scottish local bus services?___________________________________5 What role do local authorities play in Scottish local bus service provision? __________6 Statutory Quality Partnerships _____________________________________________6 Bus Quality Contracts ___________________________________________________7 Key trends in bus usage and costs _________________________________________8 Changes proposed in the Bill_____________________________________________12 Provision of local bus services by local authorities ____________________________12 Bus Service Improvement Partnerships_____________________________________12 Local service franchises_________________________________________________14 Information relating to services ___________________________________________15 Provision of information for the public -

Whole Day Download the Hansard Record of the Entire Day in PDF

Thursday Volume 648 25 October 2018 No. 195 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 25 October 2018 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2018 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 413 25 OCTOBER 2018 Oral Answers 414 Dominic Raab: The hon. Lady is right to raise this House of Commons issue,not least because Government and the pharmaceutical industry already liaise on stockpiling for far longer Thursday 25 October 2018 periods in other circumstances, including in relation to vaccines. Wewill keep it under review,but this is something The House met at half-past Nine o’clock the industry is used to doing and we are used to co-operating with it. PRAYERS Sandy Martin: In September, the Borders Delivery Group reported that 11 of the 12 major projects to [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] replace or change key IT systems were at risk of not being delivered on time or in a workable condition. Many of my constituents who work at the port of Oral Answers to Questions Felixstowe are at their wits’ end about how this is going to work. Can the Secretary of State tell us what is going to be done with those IT systems? EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION Dominic Raab: We had an extended Cabinet session last month. We looked at a whole range of action points The Secretary of State was asked— right across the piece, including some of the IT issues to No Deal: UK Border Delays which the hon.