Central Provinces and Berar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha District Gazetteers Nabarangpur

ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR DR. TARADATT, IAS CHIEF EDITOR, GAZETTEERS & DIRECTOR GENERAL, TRAINING COORDINATION GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ii iii PREFACE The Gazetteer is an authoritative document that describes a District in all its hues–the economy, society, political and administrative setup, its history, geography, climate and natural phenomena, biodiversity and natural resource endowments. It highlights key developments over time in all such facets, whilst serving as a placeholder for the timelessness of its unique culture and ethos. It permits viewing a District beyond the prismatic image of a geographical or administrative unit, since the Gazetteer holistically captures its socio-cultural diversity, traditions, and practices, the creative contributions and industriousness of its people and luminaries, and builds on the economic, commercial and social interplay with the rest of the State and the country at large. The document which is a centrepiece of the District, is developed and brought out by the State administration with the cooperation and contributions of all concerned. Its purpose is to generate awareness, public consciousness, spirit of cooperation, pride in contribution to the development of a District, and to serve multifarious interests and address concerns of the people of a District and others in any way concerned. Historically, the ―Imperial Gazetteers‖ were prepared by Colonial administrators for the six Districts of the then Orissa, namely, Angul, Balasore, Cuttack, Koraput, Puri, and Sambalpur. After Independence, the Scheme for compilation of District Gazetteers devolved from the Central Sector to the State Sector in 1957. -

Pre-Feasibility Report of Granite

PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT OF GRANITE (MINOR MINERAL) MINE Village – Kanhanpuri, Tehsil – Narharpur Dist. – Kanker, Chhattisgarh Area - 1.87 Hectare INTRODUCTION The commercial use of the term Black Granite is considerably broader than the geological use. In industry the term refer to true granite, granite gneiss and the intermediate member of the granite – gabbro series, gabbro, diabase, anorthosite , pyroxinite and dolerite called black granite, when used for polished dimension stone. Kanker is one of the large districts of Chhattisgarh and known to be densely forested and thinly populated by the tribes. The district is endowed with large number of economic rocks and minerals. There is a growing demand for Black Granite ( dolerite dyke ) and other basic rocks known as Black Granite in Kanker district. The applicant Vimal Lunia granted quarry lease for Black Granite in village – Kanhanpuri of District – Uttar Bastar ( Kanker.) The proposed area for which 1st Scheme of Mining is being prepared is located in the Jurisdiction of village – Kanhanpuri, Tahsil – Narharpur of District – Uttar Bastar ( Kanker ) , State – Chhattisgarh. There is a small but good deposit of “Black Granite” available in this village . The leased area was granted to the applicant Mr. Vimal Lunia 1st time on 2nd November 1998 for 10 years under the Madhya Pradesh Minor Mineral Rules 1996. As per the rule 18 (2) GDCR 1999 1st scheme of mining due for the period of 2014-15 to 2018-19, for this reason lessee Shri. Vimal Lunia of Jagdalpur, District – Bastar, State – Chhattisgarh submitting the 1st scheme of mining for their existing Kanhanpuri Black Granite Mine by utilizing the services of an Indian Bureau of Mines Nagpur , approved Recognized Qualified Person Mr. -

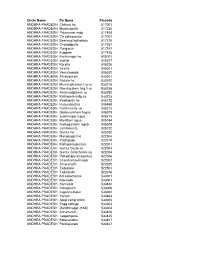

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No Mhosba Gate , Karjat Tal Karjat Dist AHMEDNAGAR KARJAT Vijay Computer Education Satish Sapkal 9421557122 9421557122 Ahmednagar 7285, URBAN BANK ROAD, AHMEDNAGAR NAGAR Anukul Computers Sunita Londhe 0241-2341070 9970415929 AHMEDNAGAR 414 001. Satyam Computer Behind Idea Offcie Miri AHMEDNAGAR SHEVGAON Satyam Computers Sandeep Jadhav 9881081075 9270967055 Road (College Road) Shevgaon Behind Khedkar Hospital, Pathardi AHMEDNAGAR PATHARDI Dot com computers Kishor Karad 02428-221101 9850351356 Pincode 414102 Gayatri computer OPP.SBI ,PARNER-SUPA ROAD,AT/POST- 02488-221177 AHMEDNAGAR PARNER Indrajit Deshmukh 9404042045 institute PARNER,TAL-PARNER, DIST-AHMEDNAGR /221277/9922007702 Shop no.8, Orange corner, college road AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Dhananjay computer Swapnil Waghchaure Sangamner, Dist- 02425-220704 9850528920 Ahmednagar. Pin- 422605 Near S.T. Stand,4,First Floor Nagarpalika Shopping Center,New Nagar Road, 02425-226981/82 AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Shubham Computers Yogesh Bhagwat 9822069547 Sangamner, Tal. Sangamner, Dist /7588025925 Ahmednagar Opposite OLD Nagarpalika AHMEDNAGAR KOPARGAON Cybernet Systems Shrikant Joshi 02423-222366 / 223566 9763715766 Building,Kopargaon – 423601 Near Bus Stand, Behind Hotel Prashant, AHMEDNAGAR AKOLE Media Infotech Sudhir Fargade 02424-222200 7387112323 Akole, Tal Akole Dist Ahmadnagar K V Road ,Near Anupam photo studio W 02422-226933 / AHMEDNAGAR SHRIRAMPUR Manik Computers Sachin SONI 9763715750 NO 6 ,Shrirampur 9850031828 HI-TECH Computer -

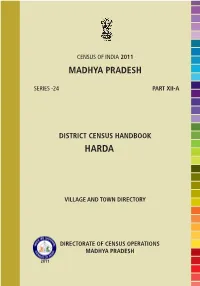

24 Part Xii-A Village and Town Directory

CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 MADHYA PRADESH SERIES -24 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK HARDA VILLAGE AND TOWN directory DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS MADHYA PRADESH 2011 SID RT TCI INDIA ES H S O ER MADHYA PRADESH A DISTRICT HARDA D e r o W d I KILOMETRES n I ! S 4 2 0 4 8 12 16 E ! o ! T D . ! R ! I C T ada T R N arm ! ! T ! ! ! ! ! R ! ! S ! ! R ! BOUNDARY : DISTRICT I ! I ! D HANDIYA ! C C.D.BLOCK ! ! ! " ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! T d TAHSIL ! ! a " ! b ! ga N ! ! n D H ha P R ( ! ! s HEADQUARTERS : DISTRICT , TAHSIL , C.D.BLOCK ! o 5 ! E H 9 ! o ! T H A ! ! ! ! VILLAGES HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION ! ! ! Sodalpur ! ! O WITH NAME ! ! S ! ! R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! L ! ! ! ! ! ! ! URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE- II, III ! ! ! A ! ! ! ! S J ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N ! ! ! ! ! (R ! ! ! ! HS 51 ! A ! ! ! C . D . B L O C K H A R D! A ! ! ! ! STATE HIGHWAY ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! TIMARNI ! H ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! C . D . B L O C K ! IMPORTANT ROADS ! ! HARDA ! ! ! A ! ! ! RS ! ! ! T I M A R N I ! ! ! ! ! Sodalpur N RAILWAY LINE WITH STATION : BROAD GAUGE ! ! ! P G ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! RIVER AND STREAM ! ! G ! 15 ! ! H ! S ! ! C J ! DEGREE COLLEGE ! ! A ! ! ! F G ! ! HOSPITAL ! ! ! B ! ! ! ! ! T ! o ! D ! B ! e A ! ! tu ! l ! ! ! ! ! REHATGAON ! ! D I ! ! ! ! ! ! R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! S ! ! ! Rehatgaon A ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! T ! ! ! ! ! S ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! i ! ! t ! ! tul ! ! ! Be ! o h ! T ! ! ! ! ! M a ! KHIRKIYA ! ! ! A R ! ! ! n C ! ! ! ! ! H i ! A ! S ! ! K R R ! ! ! ! R ! R ! ! . ! ! ! ! ! I ! SIRALI ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ( ! wa R! ! ! d ! an J Sirali ! ! om Kh ! r ! ! F ! C ! ! a ! ! ! ! ! TAHSIL w ! d C . -

A Statistical Account of Bengal

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com \l \ \ » C_^ \ , A STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF BENGAL. VOL. XVII. MURRAY AND G1BB, EDINBURGH, PRINTERS TO HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. A STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF BENGAL. BY W. W. HUNTER, B.A., LL.D., DIRECTOR-GENERAL OF STATISTICS TO THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ; ONE OF THE COUNCIL OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY ; HONORARY OR FOREIGN MEMBER OF THE ROYAL INSTITUTE OF NETHERLANDS INDIA AT THE HAGUE, OF THE INSTITUTO VASCO DA GAMA OF PORTUGUESE INDIA, OF THE DUTCH SOCIETY IN JAVA, AND OF THE ETHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY. LONDON ; HONORARY FELLOW OF . THE CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY ; ORDINARY FELLOW OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, ETC. VOL UM-E 'X'VIL ' SINGBHUM DISTRICT, TRIBUTARY STATES OF CHUTIA NAGPUR, AND MANBHUM. This Volume has been compiled by H. H. RlSLEY, Esq., C.S., Assistant to the Director-General of Statistics. TRUBNER & CO., LONDON 1877. i -•:: : -.- : vr ..: ... - - ..-/ ... PREFACE TO VOLUME XVII. OF THE STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF BENGAL. THIS Volume treats of the British Districts of Singbhum and Manbhiim, and the collection of Native States subor dinate to the Chutia Nagpu-- Commission. Minbhum, with the adjoining estate of Dhalbl1um in Singbhu1n District, forms a continuation of the plarn of Bengal Proper, and gradually rises towards the plateau -of .Chutia. Nagpur. The population, which is now coroparatrv^y. dense, is largely composed of Hindu immigrants, and the ordinary codes of judicial procedure are in force. In the tract of Singbhum known as the Kolhan, a brave and simple aboriginal race, which had never fallen under Muhammadan or Hindu rule, or accepted Brahmanism, affords an example of the beneficent influence of British administration, skilfully adjusted to local needs. -

Pre-Feasibility Report

PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT OF GRANITE (MINOR MINERAL) MINE Village – Kanhanpuri, Tehsil – Narharpur Dist. – Kanker, Chhattisgarh Area - 1.87 Hectare INTRODUCTION The commercial use of the term Black Granite is considerably broader than the geological use. In industry the term refer to true granite, granite gneiss and the intermediate member of the granite – gabbro series, gabbro, diabase, anorthosite , pyroxinite and dolerite called black granite, when used for polished dimension stone. Kanker is one of the large districts of Chhattisgarh and known to be densely forested and thinly populated by the tribes. The district is endowed with large number of economic rocks and minerals. There is a growing demand for Black Granite ( dolerite dyke ) and other basic rocks known as Black Granite in Kanker district. The applicant Vimal Lunia granted quarry lease for Black Granite in village – Kanhanpuri of District – Uttar Bastar ( Kanker.) The proposed area for which 1st Scheme of Mining is being prepared is located in the Jurisdiction of village – Kanhanpuri, Tahsil – Narharpur of District – Uttar Bastar ( Kanker ) , State – Chhattisgarh. There is a small but good deposit of “Black Granite” available in this village . The leased area was granted to the applicant Mr. Vimal Lunia 1st time on 2nd November 1998 for 10 years under the Madhya Pradesh Minor Mineral Rules 1996. As per the rule 18 (2) GDCR 1999 1st scheme of mining due for the period of 2014-15 to 2018-19, for this reason lessee Shri. Vimal Lunia of Jagdalpur, District – Bastar, State – Chhattisgarh submitting the 1st scheme of mining for their existing Kanhanpuri Black Granite Mine by utilizing the services of an Indian Bureau of Mines Nagpur , approved Recognized Qualified Person Mr. -

Princely State of Gangpur

October - 2015 Odisha Review Princely State of Gangpur Harihar Panda Abstract: The story of Odisha says a history of some thousand years ago. It has experienced a wide narration of valiant warfare, adoption of variant dynasties, insertion of public representation in monarchy and many more. Even during the English period the Feudatory system has gained an important role that has also put pressure in obtaining rights for its indigenous people. The post independent era has also witnessed a fair participation of royal family members i.e., kings, queens, Pattayats, Chhotrays, Deewans and more in democracy. The infrastructures built during state time still act as core houses for implementing development activities in our state. This article will focus on the establishment of Gangpur feudatory state and its role during the statehood and also revisit the infrastructures of that time. But many of them are still in a miserable condition. This attention may put a beam of light on them to spread our culture, conservation of history and promotion of participatory tourism. History & folklore defeated the kings of Utkala and Kosala, It is a story of more than a thousand years Chindaka-Naga chief Someshvara I also declared ago, when the entire Kalinga, Udra and Koshala to have defeated the Udra chief and captured six were under the rule of Somavamshi kings. The lakh and ninety-six villages of Kosala. Sometime ruler at Jajnagar of the entire empire Janmejay-II it is said that after the arrival of Gangas the Bhanu falls into trouble by the Gangas, Chhindaka-Nagas Ganga-III has sheltered himself here at the and Kalachuri kings. -

State Zone Commissionerate Name Division Name Range Name

Commissionerate State Zone Division Name Range Name Range Jurisdiction Name Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range I On the northern side the jurisdiction extends upto and inclusive of Ajaji-ni-Canal, Khodani Muvadi, Ringlu-ni-Muvadi and Badodara Village of Daskroi Taluka. It extends Undrel, Bhavda, Bakrol-Bujrang, Susserny, Ketrod, Vastral, Vadod of Daskroi Taluka and including the area to the south of Ahmedabad-Zalod Highway. On southern side it extends upto Gomtipur Jhulta Minars, Rasta Amraiwadi road from its intersection with Narol-Naroda Highway towards east. On the western side it extend upto Gomtipur road, Sukhramnagar road except Gomtipur area including textile mills viz. Ahmedabad New Cotton Mills, Mihir Textiles, Ashima Denims & Bharat Suryodaya(closed). Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range II On the northern side of this range extends upto the road from Udyognagar Post Office to Viratnagar (excluding Viratnagar) Narol-Naroda Highway (Soni ni Chawl) upto Mehta Petrol Pump at Rakhial Odhav Road. From Malaksaban Stadium and railway crossing Lal Bahadur Shashtri Marg upto Mehta Petrol Pump on Rakhial-Odhav. On the eastern side it extends from Mehta Petrol Pump to opposite of Sukhramnagar at Khandubhai Desai Marg. On Southern side it excludes upto Narol-Naroda Highway from its crossing by Odhav Road to Rajdeep Society. On the southern side it extends upto kulcha road from Rajdeep Society to Nagarvel Hanuman upto Gomtipur Road(excluding Gomtipur Village) from opposite side of Khandubhai Marg. Jurisdiction of this range including seven Mills viz. Anil Synthetics, New Rajpur Mills, Monogram Mills, Vivekananda Mill, Soma Textile Mills, Ajit Mills and Marsdan Spinning Mills. -

Dr. Milind Barhate (Principal) C.P

1 RE-ACCREDITATION REPORT (RAR – 2nd Cycle) (2010-11 to 2014-15) Submitted to: NATIONAL ASSESSMENT & ACCREDITATION COUNCIL BANGALORE - 560072 (NAAC) Western Region Submitted by: Dr. Milind Barhate (Principal) C.P. & Berar Education Society's C.P.& Berar College COLLEGE (Affiliated to Rashtrasant Tukdoji Maharaj Nagpur University) Nagpur (MS) Website: www.cpberar.co.in Email:[email protected] 2 College Building 3 Contents Page No Cover Page 1 College Building Photo 3 Contents 4 Preface 6 Principal‘s Message 7 IQAC 8 Criterion Wise Committees 8 Executive Summary 9 Re-Accreditation Report Profile of the Institution 14-24 Criteria-wise Analytical Report 1 Criterion I : Curricular Aspects 24-38 2 Criterion II : Teaching Learning and Evaluation 38-67 3 Criterion III : Research Consultancy and Extension 67-100 4 Criterion IV : Infrastructure and Learning Resources 101-118 5 Criterion V : Student Support and Progression 118-133 6 Criterion VI : Governance, Leadership and Management 133-151 7 Criterion VII : Innovations and Best Practices 151-166 Evaluative Reports From the Departments 1 Commerce 167-180 4 2 Marathi 180-203 3 English 203-214 4 Sanskrit 214-229 5 Economics 229-238 6 Political Science 238-245 7 Sociology 245-252 8 Psychology 252-262 9 Home Economics 262-269 10 History 269- 274 11 Physical Education 275-280 Post Accreditation Initiatives 280 Declaration by the Head of the Institution 281 Certificate of Compliance 282 Annexure 283 Approval to start college 283 Permanent Affiliation 284 Continuation of Affiliation 285-286 UGC 2 (f) 287 UGC Development Grant Letter XII Plan 288 Audit Report of Last Four Years 289-319 UGC Grant XI Plan – Utilization Certificate 320-326 Teaching Master Plan 327-331 Non Teaching Master Plan 332-336 5 Preface C.P.& Berar E.S. -

1.Conference-App DYNAMICS of GRAM PRODUCTION in MAJOR

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Applied, Natural and Social Sciences (IMPACT: IJRANSS) ISSN(P): 2347-4580; ISSN(E): 2321-8851 Special Edition, Sep 2016, 1-4 © Impact Journals DYNAMICS OF GRAM PRODUCTION IN MAJOR GRAM PRODUCING DISTRICTS OF MADHYA PRADESH MANAS GUPTA & J.K.GUPTA Department of Agriculture Economics, MGCGVV, Chitrakoot, Satna, Madhya Pradesh, India ABSTRACT An attempt was made to ascertain the growth pattern of Gram production in major Gram growing districts of Madhya Pradesh the study was conducted during the year 1992-93 to 2012-13. The result lead to conclude that the higher and significant linear growth (3.19 %) in production of Gram in the these districts, was due to significantly higher growth (7.64 %) of area followed by better growth in productivity.. The overall compound growth of Gram production in these districts was 3.28 per cent. During the study period acreage of Gram was found negative growth in Narsinghpur and Gunn districts. All other district have positive compound growth rate and significant in most of the districts. Production of Gram increased in all the districts but it was significantly in Jabalpur, Sager, Damoh, Panna, Dewas, Guna, Sehore, Raisen, Vidisha and Rajgarh districts. The compound growth rates measure in different districts between 0.67 to 6.23 per cent. The productivity of Gram is static around 1 tones/ha. so there is a big scope to increase production without increase of acreage. KEYWORDS: Gram, Production, Growth, Different INTRODUCTION Pulse crops are one of the most important group of crops in our country. That group comprises of twelve crops, Chickpea, Pigenopea, Greengram, Blackgram and Lentil are the important pulses of the group. -

Legal Limits on Religious Conversion in India

LEGAL LIMITS ON RELIGIOUS CONVERSION IN INDIA LAURA DUDLEY JENKINS* I INTRODUCTION In recent years, more and more states in India have enacted laws to restrict religious conversion, particularly targeting conversions via “force” or “allurement.” Current laws stem back to various colonial laws (including anticonversion, apostasy, and public-safety acts) in British India and several princely states. Implementing such laws seems to require judging the state of mind of the converts by assessing their motives and volition or, in other words, determining whether converts were “lured” or legitimate. In contemporary India, government assessments of the legitimacy of conversions tend to rely on two assumptions: first, that people who convert in groups may not have freely chosen conversion, and second, that certain groups are particularly vulnerable to being lured into changing their religion. These assumptions, which pervade the anticonversion laws as well as related court decisions and government committee reports, reinforce social constructions of women and lower castes as inherently naïve and susceptible to manipulation. Like “protective” laws in many other contexts, such laws restrict freedom in highly personal, individual choices and thus must be carefully scrutinized. Comparing contemporary anticonversion laws and related commission reports in the Indian states of Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Chattisgarh, Tamil Nadu, and Gujarat, reveals embedded assumptions about the vulnerability of group converts, especially women, lower castes, and tribals. The newest acts in Rajasthan (2006) and Himachal Pradesh (2007) will be briefly discussed, but an older, unimplemented law (in Arunachal Pradesh since 1978) and potential new laws under discussion (in Jharkhand and Uttarakhand) are outside the scope of this article.