The English Reformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

126613853.23.Pdf

Sc&- PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIV STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH OCTOBEK 190' V STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH 1225-1559 Being a Translation of CONCILIA SCOTIAE: ECCLESIAE SCOTI- CANAE STATUTA TAM PROVINCIALIA QUAM SYNODALIA QUAE SUPERSUNT With Introduction and Notes by DAVID PATRICK, LL.D. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1907 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION— i. The Celtic Church in Scotland superseded by the Church of the Roman Obedience, . ix ir. The Independence of the Scottish Church and the Institution of the Provincial Council, . xxx in. Enormia, . xlvii iv. Sources of the Statutes, . li v. The Statutes and the Courts, .... Ivii vi. The Significance of the Statutes, ... lx vii. Irreverence and Shortcomings, .... Ixiv vni. Warying, . Ixx ix. Defective Learning, . Ixxv x. De Concubinariis, Ixxxvii xi. A Catholic Rebellion, ..... xciv xn. Pre-Reformation Puritanism, . xcvii xiii. Unpublished Documents of Archbishop Schevez, cvii xiv. Envoy, cxi List of Bishops and Archbishops, . cxiii Table of Money Values, cxiv Bull of Pope Honorius hi., ...... 1 Letter of the Conservator, ...... 1 Procedure, ......... 2 Forms of Excommunication, 3 General or Provincial Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 8 Aberdeen Synodal Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 30 Ecclesiastical Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, . 46 Constitutions of Bishop David of St. Andrews, . 57 St. Andrews Synodal Statutes of the Fourteenth Century, vii 68 viii STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH Provincial and Synodal Statute of the Fifteenth Century, . .78 Provincial Synod and General Council of 1420, . 80 General Council of 1459, 82 Provincial Council of 1549, ...... 84 General Provincial Council of 1551-2 ... -

Richard Hooker, “That Saint-Like Man”, En Zijn Strijd Op Twee Fronten

Richard Hooker, “that saint-like man”, en zijn strijd op twee fronten Dr. Chris de Jong Renaissance, Humanisme en de Reformatie hebben in Europa een intellectuele, politieke en godsdienstige aardverschuiving veroorzaakt, die geen enkel aspect van de samenleving onberoerd liet. Toen na ongeveer anderhalve eeuw het stof was neergeslagen (1648 Vrede van Westfalen, 1660 Restauratie in Engeland), was Europa onherkenbaar veranderd. Het Protestantse noorden had zich ontworsteld aan de heerschappij van het Rooms-Katholieke zuiden. Dit raakte de meest uiteenlopende zaken: landsgrenzen waren opnieuw getrokken, dynastieke verhoudingen waren gewijzigd, politieke invloedssferen gefragmenteerd als nooit tevoren en het zwaartepunt van de Europese economie was definitief verschoven van de noordelijke oevers van de Middellandse Zee naar Duitsland en de Noordzeekusten. De door Maarten Luther in 1517 in gang gezette Reformatie heeft de eenheid van godsdienst, cultuur, taal en filosofie grotendeels doen verdwijnen. Dat niet alleen, de verbrokkeling en uitholling van het eens zo machtige Rooms-Katholieke geestelijke imperium, die al in de Middeleeuwen begonnen waren, hebben mede de omstandigheden geschapen waardoor vanaf het midden van de zeventiende eeuw een nieuwe intellectuele beweging Europa kon overspoelen: de Verlichting. In Engeland werd de omwenteling in 1534 (Act of Supremacy) in gang gezet door Koning Hendrik VIII (*1491; r. 1509-1547), een conservatief in godsdienstige zaken die niets van Luther moest hebben. Bijgestaan door de onvermoeibare “patron of preaching” Thomas Cromwell (1485-1540) zegde hij in deze 16de eeuwse Brexit de gehoorzaamheid aan Rome op en maakte zo de weg vrij voor een wereldwijde economische en politieke expansie van Engeland. Ook met de vorming van een zelfstandige Engelse nationale kerk koos Hendrik zijn eigen koers, welk beleid na zijn dood na een korte onderbreking werd voortgezet door zijn dochter, Koningin Elizabeth I (*1533; r. -

9780521633482 INDEX.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 0521633486 - A History of the English Parish: The Culture of Religion from Augustine to Victoria N. J. G. Pounds Index More information INDEX abandonment, of settlement 90–1 rail 442 Abbots Ripton, briefs 270, 271 (map) tomb 497 abortion 316–17; herbs for 316 altarage 54 Abraham and Isaac 343 Altarnon church 347, 416 absenteeism 564 Alvingham priory 63 abuse, verbal 258 Ancaster stone 402 accounts, clerical 230 Andover parish 22, 23 (map) parochial 230 Anglican liturgy 481 wardens’ 230 Anglo-Saxon churches 113 acolyte 162 Annates 229 Act of Unification 264 anticlericalism 220, 276 Adderbury, building of chancel 398–9 in London 147 adultery 315 apparition 293 Advent 331 appropriation 50–4, 62–6, 202 (map) Advowson 42, 50, 202 apse 376, 378 Ælfric’s letter 183 Aquae bajulus 188 Æthelberht, King 14 Aquinas, Thomas 161, 459 Æthelflaeda of Mercia 135 archdeaconries 42 Æthelstan, law code of 29 archdeacons 162, 181, 249 affray, in church courts 291–2; over seats 477 courts of 174–6, 186, 294–6, 299, 303 aged, support of 196 and wills 307 agonistic principle 340 archery 261–2 aisles 385–7, 386 (diag.) Arles, Council of 7, 9 ales 273, see church-ales, Scot-ales Ascension 331 Alexander III, Pope 55, 188, 292 Ashburton 146 Alkerton chapel 94 accounts of 231 All Hallows, Barking 114 church-ale at 241 All Saints, Bristol, library at 286–8 pews in 292 patrons of 410 Ashwell, graffiti at 350–1 All Saints’ Day 331, 333 audit, of wardens’ accounts 182–3 altar 309 auditory church 480 candles on 434 augmentations, court of 64 consecration of 442–3 Augustinian order 33, 56 covering of 437 Austen, Jane 501 desecration of 454 Avicenna 317 frontals 430, 437 Aymer de Valence 57 material of 442 number of 442 Bag Enderby 416 placement of 442 Bakhtin, Mikhail 336 position of 486 balance sheet of parish 236–9 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521633486 - A History of the English Parish: The Culture of Religion from Augustine to Victoria N. -

Legal Changes to the Procedure for Publishing the Banns of Marriage

LEGAL CHANGES TO THE PROCEDURE FOR PUBLISHING BANNS OF MARRIAGE The Church of England Marriage (Amendment) Measure is due to receive the Royal Assent on 19th December 2012. Section 2 of the Measure, which comes into force immediately when Royal Assent is given, makes some important changes to the statutory procedure for publishing banns of marriage. The clergy and others responsible for publishing banns need to be aware of these changes given the importance of banns being properly published. The two changes that will take effect on 19th December are– there will be statutory authority for the use of the form of words for the publication of banns contained in Common Worship: Pastoral Services (as an optional alternative to the form of words contained in the Book of Common Prayer) banns must be published on three Sundays at the ‘principal service’ (rather than as at present at ‘morning service’) and, as an option, they may additionally be published at any other service on those three Sundays. Alternative form of words for banns From 19th December there will be statutory authority for the alternative form of words for the publication of banns of marriage contained in Common Worship. o The clergy and others responsible for publishing banns may then use either the form of words set out in the rubric at the beginning of the Form of the Solemnization of Matrimony contained in the Book of Common Prayer or they may use the form of words set out at paragraph 2 in “Notes to the Marriage Service” in Common Worship: Pastoral Services. -

Book of Common Prayer, Formatted As the Original

The Book of Common Prayer, Formatted as the original This document was created from a text file through a number of interations into InDesign and then to Adobe Acrobat (PDF) format. This document is intended to exactly duplicate the Book of Common Prayer you might find in your parish church; the only major difference is that font sizes and all dimensions have been increased slightly (by about 12%) to adjust for the size difference between the BCP in the pew and a half- sheet of 8-1/2 X 11” paper. You may redistribute this document electronically provided no fee is charged and this header remains part of the document. While every attempt was made to ensure accuracy, certain errors may exist in the text. Please contact us if any errors are found. This document was created as a service to the community by Satucket Software: Web Design & computer consulting for small business, churches, & non-profits Contact: Charles Wohlers P. O. Box 227 East Bridgewater, Mass. 02333 USA [email protected] http://satucket.com Concerning the Service Christian marriage is a solemn and public covenant between a man and a woman in the presence of God. In the Episcopal Church it is required that one, at least, of the parties must be a baptized Christian; that the ceremony be attested by at least two witnesses; and that the marriage conform to the laws of the State and the canons of this Church. A priest or a bishop normally presides at the Celebration and Blessing of a Marriage, because such ministers alone have the function of pronouncing the nuptial blessing, and of celebrating the Holy Eucharist. -

The Constitutional Prohibition on Imposing Religious Observances

THE CONSTITUTIONAL PROHIBITION ON IMPOSING RELIGIOUS OBSERVANCES LUKE B ECK* This article provides the first thorough analysis of the religious observances clause of the Australian Constitution, which provides: ‘The Commonwealth shall not make any law … for imposing any religious observance.’ The article explains the origins of the clause and the mischiefs it aimed to prohibit, and presents a doctrinal account of the meaning and operation of the clause informed by the relevant history. The article begins by examining the social and political background to the drafting of the religious observances and its drafting history at the Australasian Federal Convention of 1897–98. The article then presents a doctrinal analysis of the meaning and operation of the religious observances clause by drawing on insights from the legislative histories of compulsory religious observance in the United Kingdom and colonial Australia. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 494 II The Political and Social Background to the Religious Observances Clause .... 495 III Drafting History of the Religious Observances Clause ...................................... 500 A The Argument Advanced at the Convention for Section 116 ............... 501 B The Development of the Language of Section 116 at the Convention 502 IV The Convention’s Discussion of the Meaning of the Religious Observances Clause ................................................................................................ -

Guidebook for the Clergy

General Register Office Guidebook for The Clergy General Register Office Issued: 2011 Last updated: February 2015 Contents Page Introduction 4 Marriage 1 General • Roles and responsibilities 5 • Hours and place of marriage 5 • Restrictions on marriage 6 • Access 6 • Witnesses 6 • Registration stock 6 • Missing or stolen safe or registration stock 7 • Damaged register books 7 • Ink 7 2 Preliminaries • Preliminaries to Marriage 8 • Ecclesiastical Preliminaries 8 • Superintendent Registrar's Certificate in lieu of Ecclesiastical 8 Preliminaries • Nationality requirements 9 • European Economic (EEA) Nationals 9 • Non European Economic (EEA) Nationals 9 • Evidence of British, EEA or Swiss Nationality 9 • Evidence of current use of name 10 • Giving notice of intent to marry 11 • Qualifying connection 11 • Notice Period 12 • One party resident in Scotland 13 • One party resident in Ireland 13 • Publication of banns - service personnel 13 • Publication of banns on board HM ships 13 • Two marriage ceremonies on the same day 13 • Religious ceremony after a civil marriage 14 • Re-marriage 14 3 Ceremony • Pre-marriage checks 15 • Marriage by Superintendent Registrar’s Certificate 15 • Pre-marriage questions 15 • Forced marriages 16 • Sham marriage 16 • Mental capacity 17 4 Registrations • Marriage registers 18 • Commencement of entries 18 • Completing the register entries 19 • Description of authority on which marriage was solemnized 22 1 • Examination of entry by the parties to the marriage 22 • Signing the entry 22 • Bilingual registration in Wales -

Elizabeth Ii

Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 CH. 52 ELIZABETH II 1969 CHAPTER 52 An Act to promote the reform of the statute law by the repeal, in accordance with recommendations of the Law Commission, of certain enactments which (except in so far as their effect is preserved) are no longer of practical utility, and by making other provision in connection with the repeal of those enactments. [22nd October 19691 BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- 1. The enactments mentioned in the Schedule to this Act are Repeal of hereby repealed to the extent specified in column 3 of the Schedule, enactments. 2.-(l) In proceedings by way of quare impedit commenced Advowsons. within six months of induction, judgment shall be given for the removal of an incumbent instituted to fill the vacancy, if he was instituted on a presentation made without title and is made a defendant to the proceedings. (2) Where the Crown presents to a benefice which is full of an incumbent, effect shall not be given to the presentation without judgment having been given for the removal of the incumbent in proceedings by way of quare impedit brought by or on behalf of the Crown. Subsection (1) above shall apply in relation to proceedings so brought whether or not they are commenced within the period of six months therein referred to. (3) The provisions of this section shall have effect in place of chapter 5 of the Statute of Westminster, the Second, chapter 10 of the statute of uncertain date concerning the King's prerogative and chapter 1 of 13 Ric. -

Understanding Calvinism: B

Introduction A. Special Terminology I. The Persons Understanding Calvinism: B. Distinctive Traits A. John Calvin 1. Governance Formative Years in France: 1509-1533 An Overview Study 2. Doctrine Ministry Years in Switzerland: 1533-1564 by 3. Worship and Sacraments Calvin’s Legacy III. Psycology and Sociology of the Movement Lorin L Cranford IV. Biblical Assessment B. Influencial Interpreters of Calvin Publication of C&L Publications. II. The Ideology All rights reserved. © Conclusion INTRODUCTION1 Understanding the movement and the ideology la- belled Calvinism is a rather challenging topic. But none- theless it is an important topic to tackle. As important as any part of such an endeavour is deciding on a “plan of attack” in getting into the topic. The movement covered by this label “Calvinism” has spread out its tentacles all over the place and in many different, sometimes in conflicting directions. The logical starting place is with the person whose name has been attached to the label, although I’m quite sure he would be most uncomfortable with most of the content bearing his name.2 After exploring the history of John Calvin, we will take a look at a few of the more influential interpreters of Calvin over the subsequent centuries into the present day. This will open the door to attempt to explain the ideology of Calvinism with some of the distinctive terms and concepts associated exclusively with it. I. The Persons From the digging into the history of Calvinism, I have discovered one clear fact: Calvinism is a religious thinking in the 1500s of Switzerland when he lived and movement that goes well beyond John Calvin, in some worked. -

Marriage Act CAP

LAWS OF SAINT CHRISTOPHER AND NEVIS Marriage Act CAP. 12.09 1 Revision Date: 31 Dec 2002 ST. CHRISTOPHER AND NEVIS CHAPTER 12.09 MARRIAGE ACT Revised Edition showing the law as at 31 December 2002 This is a revised edition of the law, prepared by the Law Revision Commissioner under the authority of the Law Revision Act, No. 9 of 1986. This edition contains a consolidation of the following laws— Page MARRIAGE ACT 3 Act 4 of 1915 … in force 1st January 1918 Amended by: Act 5 of 1967 Act 6 of 1976 Act 7 of 1987 Act 4 of 2002 Prepared under Authority by The Regional Law Revision Centre Inc. ANGUILLA LAWS OF SAINT CHRISTOPHER AND NEVIS Marriage Act CAP. 12.09 3 Revision Date: 31 Dec 2002 CHAPTER 12.09 MARRIAGE ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY 1. Short title 2. Interpretation PART II REGISTRAR-GENERAL, REGISTRARS AND MARRIAGE DISTRICTS, MARRIAGE OFFICERS, REGISTERED BUILDINGS, ETC. 3. Appointment of Registrar General and Registrars 4. Appointment of marriage officers 5. Power to refuse to act 6. Application for appointment as a marriage officer 7. Notification of ministers of religion ceasing to act 8. Marriage officer may resign 9. Notification in Gazette 10. Temporary absence of marriage officers 11. Power to cancel appointment 12. Register of marriage officers. Form A. First Schedule 13. Applications, notices, etc., to be sent to Registrar-General 14. Appointments to be published in Gazette 15. Marriage notice books 16. Powers of Registrar-General 17. Appointment of offices 18. Registration of buildings in use at commencement of Act 19. -

Marriage Act 1944

Q UO N T FA R U T A F E BERMUDA MARRIAGE ACT 1944 1944 : 25 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Interpretation 2 Marriage Officers [repealed] 3 Meaning of “Marriage Officer” 4 Licensing of ministers to be Marriage Officers; revocation of licences 5 Saving of rights of ministers under former Act [omitted] 6 Registrar of Marriages 7 Registrar to keep list of marriage officers 8 Performance of marriages 9 General prerequisites of marriage 10 Notice of marriage 11 Publication of banns of marriage 12 Certificate of Marriage Officer [repealed] 13 Marriage Notice Book; public notice 14 Issue of Registrar’s certificate 15 Consent to marriage of minors 16 Application for consent of Judge 17 Caveat may be entered 18 Duties of Registrar on entry of caveat 19 Powers of Judge to whom caveat referred 20 Special licence 21 Commonwealth citizens intending marriage; one in Bermuda another in United Kingdom [repealed] 22 Certificate or special licence lapses within 3 months 23 Celebration of marriage by Marriage Officer 24 Contracting of marriage before Registrar 25 Marriage in extremis 26 Marriage of divorced person; right of Marriage Officer to refuse to officiate 27 Other circumstances in which Marriage Officer may refuse to officiate 1 MARRIAGE ACT 1944 28 Void marriages 29 Registration of marriages 30 Any person may search registers and obtain copies of particulars other than racial colour or origin 31 Registrar may require information 32 Alterations and amendments 33 Offences 34 Evidence of marriage by means of Registers 35 Annual report 36 Use of foreign language -

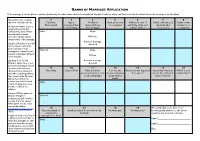

Banns and Marriage Application Form

BANNS OF MARRIAGE APPLICATION If the marriage is to take place in another parish, only the white boxes need to be completed. Complete both the white and blue boxes for the church where the marriage is to take place. One person may complete 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 this form on behalf of both. Full name Age at Condition Rank, profession Address at time of Father’s full name (if Father’s rank, Block capitals proposed date (delete whichever or occupation publishing banns, and deceased, add profession or At least two weeks’ notice is of wedding does not apply) phone number “deceased”) occupation required before the first reading of the banns. Banns (Man) Single must be read on three successive Sundays within Widower three months of the marriage. Previous marriage (Section 3) If either of you will dissolved not be 18 years old by the proposed date of your (Woman) Single marriage the consent of your parents or guardians will need Widow to be obtained. (Sections 4, 11, 12) The Previous marriage Church’s official rules do not dissolved permit the marriage in church of anyone who has been 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 divorced from a husband or Nationality Date of birth Have you been If so, was the Have you been baptised? Since when have you Which is your wife who is still living,without previously married or in previous marriage If so, where? lived at the address in parish church? the consent of the Diocesan a civil partnership? terminated by section 6 above? Bishop.