Vocality and Deaf Theatre When a Heari

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward Albee's at Home at The

CAST OF CHARACTERS TROY KOTSUR*............................................................................................................................PETER Paul Crewes Rachel Fine Artistic Director Managing Director RUSSELL HARVARD*, TYRONE GIORDANO..........................................................................................JERRY AND AMBER ZION*.................................................................................................................................ANN JAKE EBERLE*...............................................................................................................VOICE OF PETER JEFF ALAN-LEE*..............................................................................................................VOICE OF JERRY PAIGE LINDSEY WHITE*........................................................................................................VOICE OF ANN *Indicates a member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of David J. Kurs Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Artistic Director Production of ACT ONE: HOMELIFE ACT TWO: THE ZOO STORY Peter and Ann’s living room; Central Park, New York City. EDWARD ALBEE’S New York City, East Side, Seventies. Sunday. Later that same day. AT HOME AT THE ZOO ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION STAFF STARRING COSTUME AND PROPERTIES REHEARSAL STAGE Jeff Alan-Lee, Jack Eberle, Tyrone Giordano, Russell Harvard, Troy Kotsur, WARDROBE SUPERVISOR SUPERVISOR INTERPRETER COMBAT Paige Lindsey White, Amber Zion Deborah Hartwell Courtney Dusenberry Alek Lev -

Literary Guide

AMBITIOUS & MOVING NEW PLAY WRITTEN AND & DIRECTED BY CRAIG I WAS MOST LUCAS ALIVE WITH YOU CURRICULUM GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Standards 3 Guidelines for Attending the Theatre 4 Important Notes 5 Artists 6 Themes for Writing & Discussion 9 Mastery Assessment 13 For Further Exploration 15 Suggested Activities 24 © Huntington Theatre Company Boston, MA 02115 June 2016 No portion of this curriculum guide may be reproduced without written permission from the Huntington Theatre Company’s Department of Education & Community Programs Inquiries should be directed to: Donna Glick | Director of Education [email protected] This curriculum guide was prepared for the Huntington Theatre Company by: Alexandra Truppi / Manager of Curriculum & Instruction Pascale Florestal / Education & Community Associate Marisa Jones / Education Associate with contributions by: Donna Glick | Director of Education COMMON CORE STANDARDS IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS STANDARDS: Student Matinee performances and pre-show workshops provide unique opportunities for experiential learning and support various combinations of the Common Core Standards for English Language Arts. They may also support standards in other subject areas such as Social Studies and History, depending on the individual play’s subject matter. Activities are also included in this Curriculum Guide and in our pre-show workshops that support several of the Massachusetts state standards in Theatre. Other arts areas may also be addressed depending on the individual play’s subject matter. Reading Literature: Key Ideas and Details 1 • Grades 11-12: Analyze how an author’s choices concerning how • Grades 9-10: Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to sup- to structure specific parts of a text (e.g., the choice of where to port analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences begin or end a story, the choice to provide a comedic or tragic drawn from the text. -

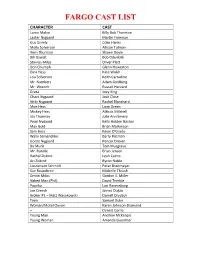

Fargo Cast List

FARGO CAST LIST CHARACTER CAST Lorne Malvo Billy Bob Thornton Lester Nygaard Martin Freeman Gus Grimly Colin Hanks Molly Solverson Allison Tolman Vern Thurman Shawn Doyle Bill Oswalt Bob Odenkirk Stavros Milos Oliver Platt Don Chumph Glenn Howerton Gina Hess Kate Walsh Lou Solverson Keith Carradine Mr. Numbers Adam Goldberg Mr. Wrench Russell Harvard Greta Joey King Chazz Nygaard Josh Close Nitty Nygaard Rachel Blanchard Moe Hess Liam Green Mickey Hess Atticus Mitchell Ida Thurman Julie Ann Emery Pearl Nygaard Kelly Holden Bashar Max Gold Brian Markinson Sam Hess Kevin O’Grady Wally Semenchko Barry Flatman Gordo Nygaard Pencer Drever Bo Munk Tom Musgrave Mr. Rundle Brian Jensen Rachel Ziskind Leah Cairns Ari Ziskind Byron Noble Lieutenant Schmidt Peter Breitmayer Sue Roundtree Michelle Thrush Dmitri Milos Gordon S. Miller Naked Man (Phil) David Trimble Paprika Lori Ravensborg Joe Creech James Dugan Broker #1 – Matt Wasakowski Darrell Orydzuk Teen Samuel Duke Woman/Motel Owner Karen Johnson-Diamond -- Dennis Corrie Young Man Andrew McKenzie Young Woman Amanda Guenther FARGO CASTING SCENE SELECTION FOR BLUE RIBBON PANEL/ RACHEL TENNER CD 1 EPISODE 101 3) Insurance Scene with the Couple 5:27- 6:10 Starts with: “So, that’s uh,…like I said” Ends with “I work at the library MARTIN FREEMAN/ ANDREW NEIL MCKENZIE (Young Man) / AMANDA GUETHNER (Young woman) 4) Sam Threatening Martin 9:14- 10:15 Starts With: “18 years, huh?” ends with Lester hitting the window and a little laugh from Sam MARTIN FREEMAN/ KEVIN O’GRADY (Sam HEss) / ATTICUS MITCHELL -

Innovation and Inclusion : the Americans with Disabilities Act at 20

S. HRG. 111–986 INNOVATION AND INCLUSION: THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT AT 20 HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON COMMUNICATIONS, TECHNOLOGY, AND THE INTERNET OF THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MAY 26, 2010 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 66–489 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:09 May 27, 2011 Jkt 664898 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\66489.TXT SCOM1 PsN: JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas, Ranking JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada BARBARA BOXER, California JIM DEMINT, South Carolina BILL NELSON, Florida JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARIA CANTWELL, Washington ROGER F. WICKER, Mississippi FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey GEOGE S. LEMIEUX, Florida MARK PRYOR, Arkansas JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri DAVID VITTER, Louisiana AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas TOM UDALL, New Mexico MIKE JOHANNS, Nebraska MARK WARNER, Virginia MARK BEGICH, Alaska ELLEN L. DONESKI, Staff Director JAMES REID, Deputy Staff Director BRUCE H. ANDREWS, General Counsel ANN BEGEMAN, Republican Staff Director BRIAN M. HENDRICKS, Republican General Counsel NICK ROSSI, Republican Chief Counsel SUBCOMMITTEE ON COMMUNICATIONS, TECHNOLOGY, AND THE INTERNET JOHN F. -

1909-1910 Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University

OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVERSITY Deceased during the Academical Year ending in JUNE, t9tO, INCLUDING THE RECORD OF A FEW WHO DIED PREVIOUSLY HITHERTO UNREPORTED [Presented at the meeting of the Alumni, June 21st, 1910] [No io of the Fifth Printed Series, and No 69 of the whole Record] OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVERSITY Deceased during the Academical Year ending in JUNE, 1910, Including the Record of a few who died previously, hitherto unreported [PRESENTED AT THE MEETING OF THE ALUMNI, JUNE 21st, 1910] [No 10 of the Fifth Printed Series, and No 69 of the whole Record] YALE COLLEGE (ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT) 1838 CHESTER DUTTON, eldest of the eleven children of Daniel Punderson and Nancy (Matthews) Dutton, was born March 24, 1814, in Watertown, Conn Since the death of Dr Gurdon Wads worth Russell of the Class of 1837 in the Medical School m February, 1909, he had been the oldest living graduate of the University One classmate, Hon. Henry Parsons Hedges, survives him He was fitted for college under the instruction of his uncle, Hon Henry Dutton (BA Yale 1818), teaching school in the intervals of study, and working until he was 18 years old on the farm of his father which has been the home of the family for six generations. He joined the class at the beginning of Sophomore year His ambition on entering college was to become a lawyer, but a serious throat affection changed his plans, and on graduation he taught school for about three years in 11 56 YALE UNIVERSITY Alexandria, Ya , and Bristol, Conn, but since 1842 had been a farmer He was at Wolcott, N. -

Broadway, Film, and TV Star Russell Harvard Starring As Tommy in Open Circle Theatre’S the Who's Tommy

Open Circle Theatre produces 500 King Farm Blvd., #102 high-quality, inventive theatre Rockville, MD 20850 productions that provide 240/683-8934 opportunities for professional [email protected] theatre artists with and without www.opencircletheatre.org disabilities. NEWS RELEASE Broadway, Film, and TV Star Russell Harvard Starring as Tommy in Open Circle Theatre’s The Who's Tommy For Immediate Release: Contact: Doretha “Doe” Dixon September 6, 2016 240/683-8934 [email protected] SILVER SPRING, MD -- Open Circle Theatre (OCT) announces the casting of Russell Harvard, Broadway, film, and TV star, to play the lead in its upcoming production of The Who’s Tommy (Music and Lyrics by Pete Townshend, Book by Pete Townshend and Des McAnuff) running October 27 through November 20, 2016 at the Silver Spring Black Box Theatre. Russell Harvard has been recognized in the Broadway revival of Spring Awakening (Deaf West Theatre), the Boston premiere of I Was Most Alive With You (Huntington Theatre) for the role of Knox, and the New York premiere of Tribes (Barrow Street Theatre) for the role of Billy, for which he received a 2012 Theatre World Award for Outstanding Debut Performance and nominations for Drama League, Outer Critics Circle, and Lucille Lortel Awards for Outstanding Lead Actor. He is well known for appearing in the award-winning film There Will Be Blood as Adult HW. Russell played the villain Mr. Wrench in the critically acclaimed Fargo series on FX Network. He also portrayed Matt Hamill, a UFC fighter, in The Hammer, based on a true story. “This is OCT's first production that directly comments on disability, so we wanted to push the conversation and confront common stereotypes. -

Deafweekly December 5, 2012 Deafweekly

Deafweekly December 5, 2012 deafweekly December 5, 2012 Vol. 9, No. 7 Editor: Tom Willard Deafweekly is an independent news report for the deaf and hard-of-hearing community that is mailed to subscribers on Wednesdays and available to read at www.deafweekly.com. These are the actual headlines and portions of recent deaf-related news articles, with links to the full story. Minor editing is done when necessary. Deafweekly is copyrighted 2012 and any unauthorized use is prohibited. Please support our advertisers; they make it possible for you to receive Deafweekly. SIGN UP HERE for a free subscription. Be sure to open the confirmation email and click on the link to activate your subscription. It is required by law and prevents others from signing you up without your permission. ADDRESS CHANGES are self serve. Simply unsubscribe using the link at the bottom of every newsletter, then sign up for a subscription with your new address. Last issue's most-read story: SANTORUM'S NEW CAUSE: OPPOSING THE DISABLED / The Washington Post Last week's website page views: 7,277 Deafweekly subscribers as of today: 4,975 ADVERTISE IN DEAFWEEKLY FOR $20 OR LESS PER WEEK +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ NATIONAL +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Houston, TX HOUSING AUTHORITY TO PAY FEE FOR DEAF RESIDENT The Houston Housing Authority has agreed to pay rental assistance and to change its policy in a settlement of a complaint by a deaf resident who said the agency refused to provide a sign language interpreter at her eligibility hearing. The authority paid $4,251 in rental payments for the time when the woman's assistance was denied, according to the U.S. -

Casting, Stigma, and Difference in Broadway Musicals Since "A Chorus Line" (1975)

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 Broadway Bodies: Casting, Stigma, and Difference in Broadway Musicals Since "A Chorus Line" (1975) Ryan Donovan The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3084 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BROADWAY BODIES: CASTING, STIGMA, AND DIFFERENCE IN BROADWAY MUSICALS SINCE A CHORUS LINE (1975) by RYAN DONOVAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre and Performance in partiaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 RYAN DONOVAN ALL Rights Reserved ii Broadway Bodies: Casting, Stigma, and Difference in Broadway MusicaLs Since A Chorus Line (1975) by Ryan Donovan This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre and Performance in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy. ________________ ______________________________________ Date David Savran Chair of Examining Committee ________________ ______________________________________ Date Peter EckersaLL Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Jean Graham-Jones ELizabeth WolLman THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Broadway Bodies: Casting, Stigma, and Difference in Broadway MusicaLs Since A Chorus Line (1975) by Ryan Donovan Advisor: David Savran “You’re not fat enough to be our fat girl.” “Dance like a man.” “Deaf people in a musicaL!?” These three statements expose how the casting process for Broadway musicaLs depends upon making aesthetic disquaLifications. -

Alexandru Ioan Cuza

LINGUACULTURE 1, 2016 “THIS IS A […] STORY;”” THE REFUSAL OF A MASTER TEXT IN NOAH HAWLEY’S FARGO ALLEN H. REDMON Texas A&M University Central Texas, USA Abstract Each episode of Noah Hawley’s first two seasons of Fargo begins with the same claim: “this is a true story.” The claim might invite the formation of what Thomas Leitch (2007) calls a “privileged master text,” except that Hawley undermines the creation of such a text in at least two ways. On the one hand, Hawley uses his truth claim as a way to direct his audience into the film he is adapting – Joel and Ethan Coen’s (1996) film by the same name. Hawley ensures throughout his first season that those who know or who come-to-know the Coens’ work will recognize his story as an extension of the Coens’s world. Hawley references the Coens’ world so much that his audience is never entirely outside the Coens’ universe, and certainly not in any world a story based on a true event might pretend to occupy. At the same time, Hawley allows different speakers to make the opening truth claim by the end of his second season, which further prevents his truth assertion from locating viewers in any actual world. Hawley’s second move reveals that true stories are always subjective stories, which means they are always constructed stories. In this way, a true story is no more definitive than any other story. All stories are, in keeping with Jorge Luis Borges’ attitude toward definitive texts, only a draft or a version of a story. -

Balancing the Theatre-Going Experience for Deaf and Hearing Audiences

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE The Aesthetics of Deaf West Theatre: Balancing the Theatre-Going Experience for Deaf and Hearing Audiences A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of the Arts in Theatre By Brandice Rafus-Brenning May 2018 Copyright by Brandice Rafus-Brenning 2018 ii The thesis of Brandice Rafus-Brenning is approved: ____________________________________ ____________________ Kari Hayter, MFA Date ____________________________________ ____________________ Dr. Lissa Stapleton Date ____________________________________ ____________________ Dr. Hillary Miller, Chair Date California State University, Northridge iii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge and thank Deaf West Theatre for their incredible work. You inspired me to write this thesis and I look forward to enjoying your productions for many years to come. I would also like to acknowledge and express my gratitude for Kanta Kochhar-Lindgren’s theories and insightful research. Eboni, my amazing wife- Thank you for being my biggest supporter and sticking with me through the rollercoaster that is graduate school. Lastly, I would like to thank my committee for their support, insights, and assistance during this process. As well, my fellow graduate students – Thank you for the much- needed moments of levity and for being my sounding boards throughout this challenging process. iv Dedication For Eboni Rafus-Brenning My love, my wife, my best friend, and my favorite proof-reader. Thank you for all that -

Deafweekly January 2, 2008 Deafweekly

Deafweekly January 2, 2008 deafweekly January 2, 2008 Vol. 4, No. 5 Editor: Tom Willard Deafweekly is an independent news report for the deaf and hard-of-hearing community that is mailed to subscribers every Wednesday and available to read at www.deafweekly.com. Please visit our website to read current and back issues, sign up for a subscription and advertise. Deafweekly is copyrighted 2007 and any unauthorized use, including reprinting of news, is prohibited. Please support our advertisers; they make it possible for you to receive Deafweekly at no charge. ++++ADV+++++ADV+++++ADV++++ Receive VRS Calls Your Way! Use VRS? Get a My IP Relay Number and receive relay calls via your PC, wireless device or even VRS! My IP Relay Number Does It All: Relay calls available through a PC, wireless devices, or VRS Make and receive calls anywhere you are connected Your personal phone number is a local number Want more information? 1) Go to www.ip-vrs.com, and then 2) click on VRS Call Me to watch a video clip about this! One Site for All Your Relay Needs IP-RELAY.com > http://www.ip-relay.com/ IP-VRS > http://www.ip-vrs.com/ MY IP RELAY > http://www.ip-relay.com/myiprelay.html MY IP RELAY NUMBER > http://www.ip-relay.com/myiprelaynumber.html WIRELESS IP-RELAY.com > http://www.ip-relay.com/wireless.html ++++ADV+++++ADV+++++ADV++++ +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ NATIONAL http://www.deafweekly.com/backissues/010208.htm[6/16/2011 9:56:08 AM] Deafweekly January 2, 2008 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ WOMAN LEAVES $6 MILLION FOR GALLAUDET Gallaudet University announced last month that it has received one of its largest gifts in history. -

27Th Annual Lucille Lortel Awards Nominations Announced

Press Chris Kanarick Amanda Bullock Contacts: [email protected] [email protected] ID Public Relations 212.334.0333 27th Annual Lucille Lortel Awards Nominations Announced Once leads nominations for a musical with 7; Tribes leads for a play with 6 nominations; Voca People to receive the award for Outstanding Alternative Theatrical Experience New York, NY (March 29, 2012) ʹ Nominations in 14 categories were announced today by the Off- Broadway League for the 2012 Lucille Lortel Awards for Outstanding Achievement Off-Broadway. This LJĞĂƌ͛Ɛ ceremony will once again benefit The Actors Fund. The Lortel Awards will be handed out on Sunday, May 6, 2012 at NYU Skirball Center beginning at 7:00pm EST. This year, members of the general public are again welcome to attend the 7:00pm ceremony. Public tickets are $75.00 and will be available starting March 30, 2012, via phone at 212.352.3101, online at www.nyuskirball.org and in person at the Skirball Center's Shagan Box Office, at 556 LaGuardia (Tuesday ʹ Sunday from 12 ʹ 6pm). Highlights this year include the fourth nomination in five years for director David Cromer, who won three consecutive awards from 2008 ʹ 2010. Sam Gold is a double nominee this year for directing Look Back in Anger and The Big Meal. Oscar-nominated actress Carey Mulligan receives her first Lucille Lortel Award nomination for Outstanding Lead Actress for her Off-Broadway debut in Through a Glass Darkly. dŽĚĂLJ͛ƐŶŽŵŝŶĞĞƐũŽŝŶƉƌĞǀŝŽƵƐůLJĂŶŶŽƵŶĐĞĚƐƉĞĐŝĂůĂǁĂƌĚƌĞĐŝƉŝĞŶƚƐZŝĐŚĂƌĚ&ƌĂŶŬĞů͕ǁŚŽǁŝůůƌeceive the Lifetime Achievement Award; Richard Foreman, who will be inducted onto the famed PlaywrigŚƚƐ͛ Sidewalk; and the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY), for Service to Off-Broadway.