The Problem of Competition Among Domestic Trunk Airlines - Part II, 21 J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2013 Air Line Pilot 1 @Wearealpa PRINTED in the U.S.A

Protecting Our Future Page 20 Follow us on Twitter September 2013 Air Line Pilot 1 @wearealpa PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. PRINTED IN SEPTEMBER 2013 • VoluME 82, NuMBER 9 17 24 20 About the Cover A Delta B-757 landing at COMMENTARY Minneapolis–St. Paul International 4 Take Note Airport. Photo by Complete the Pass 28 The Capt. Eric Cowan (Compass). 5 Aviation Matters Military Download a QR Lifelong Lessons Channel: reader to your smartphone, scan the code, and 6 Weighing In limited read the magazine. Prepared for the Future but 30 Air Line Pilot (ISSN 0002-242X) is pub lished Reemerging monthly by the Air Line Pilots Association, Inter national, affiliated with AFL-CIO, SPECIAL SECTION Resource CLC. Editorial Offices: 535 Herndon 34 AlPA Represents Parkway, PO Box 1169, Herndon, VA 20 Building the for Airline Pilot 20172-1169. Telephone: 703-481-4460. Communications Fax: 703-464-2114. Copyright © 2013—Air Airline Piloting Recruitment Line Pilots Association, Inter national, all rights reserved. Publica tion in any form Profession for the 29 Community 36 our Stories without permission is prohibited. Air Line Braniff Pilot Refuses to Take Pilot and the ALPA logo Reg. U.S. Pat. Future outreach to Primary and T.M. Office. Federal I.D. 36-0710830. Retirement Sitting Down Periodicals postage paid at Herndon, VA 22 Mentoring a New and Secondary 20172, and additional offices. Schools 37 The landing Postmaster: Send address changes to Generation of Airline Air Line Pilot, PO Box 1169, Herndon, VA Pilots How Does Your University 20172-1169. Rank? Canadian Publications Mail Agreement DEPARTMENTS #40620579: Return undeliverable maga- 24 Auburn’s Flight zines sent to Canadian addresses to 2835 Kew Drive, Windsor, ON, Canada N8T 3B7. -

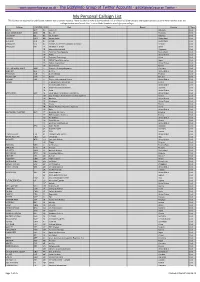

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Airline Service Abandonment and Consolidation - a Chapter in the Battle Ga Ainst Subsidization Ronald D

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Southern Methodist University Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 32 | Issue 4 Article 2 1966 Airline Service Abandonment and Consolidation - A Chapter in the Battle ga ainst Subsidization Ronald D. Dockser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Ronald D. Dockser, Airline Service Abandonment and Consolidation - A Chapter in the Battle against Subsidization, 32 J. Air L. & Com. 496 (1966) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol32/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. AIRLINE SERVICE ABANDONMENT AND CONSOLIDATION - A CHAPTER IN THE BATTLE AGAINST SUBSIDIZATIONt By RONALD D. DOCKSERtt CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION II. THE CASE FOR ELIMINATING SUBSIDY A. Subsidy Cost B. Misallocation Results Of Subsidy C. CAB Present And Future Subsidy Goals III. PROPOSALS FOR FURTHER SUBSIDY REDUCTION A. Federal TransportationBill B. The Locals' Proposal C. The Competitive Solution 1. Third Level Carriers D. Summary Of Proposals IV. TRUNKLINE ROUTE ABANDONMENT A. Passenger Convenience And Community Welfare B. Elimination Of Losses C. Equipment Modernization Program D. Effect On Competing Carriers E. Transfer Of Certificate Approach F. Evaluation Of Trunkline Abandonment V. LOCAL AIRLINE ROUTE ABANDONMENT A. Use-It-Or-Lose-It 1. Unusual and Compelling Circumstances a. Isolation and Poor Surface Transportation b. -

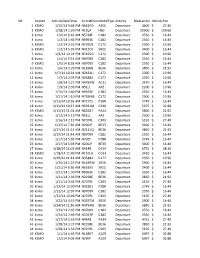

Rslt Airport Activitydatetime Aircraftnummodeltypeactivity

rslt Airport ActivityDateTime AircraftNumModelTypeActivity MaxLandin ActivityFee 1 KSMO 1/10/14 9:43 PM N661PD AS50 Departure 4600 $ 27.40 2 KSMO 1/18/14 1:20 PM N15LA H60 Departure 20000 $ 109.60 3 ksmo 1/2/14 9:16 AM N5738F C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 4 ksmo 1/2/14 1:43 PM N9955E C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 5 KSMO 1/2/14 3:52 PM N739DZ C172 Departure 2300 $ 10.96 6 KSMO 1/2/14 5:03 PM N412DJ SR22 Departure 3400 $ 16.44 7 ksmo 1/3/14 12:24 PM N7425G C172 Departure 2300 $ 10.96 8 ksmo 1/4/14 9:51 AM N97099 C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 9 KSMO 1/5/14 8:28 AM N97099 C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 10 ksmo 1/6/14 2:29 PM N18308 BE36 Departure 3850 $ 21.92 11 ksmo 1/7/14 10:24 AM N2434U C172 Departure 2300 $ 10.96 12 ksmo 1/7/14 2:33 PM N35884 C177 Departure 2350 $ 10.96 13 ksmo 1/8/14 1:21 PM N4792W AC11 Departure 3140 $ 16.44 14 ksmo 1/9/14 2:33 PM N51LL AA5 Departure 2200 $ 10.96 15 ksmo 1/10/14 2:40 PM N9955E C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 16 ksmo 1/11/14 1:10 PM N739MB C172 Departure 2300 $ 10.96 17 ksmo 1/13/14 10:26 AM N727CS P28R Departure 2749 $ 16.44 18 ksmo 1/13/14 10:27 AM N5931M C340 Departure 5975 $ 32.88 19 KSMO 1/13/14 11:01 AM N8328T PA44 Departure 3800 $ 21.92 20 ksmo 1/13/14 5:13 PM N51LL AA5 Departure 2200 $ 10.96 21 ksmo 1/16/14 2:12 PM N707RL C303 Departure 5150 $ 27.40 22 ksmo 1/17/14 7:36 AM N200JF BE33 Departure 3400 $ 16.44 23 ksmo 1/17/14 11:13 AM N2111Q BE36 Departure 3850 $ 21.92 24 ksmo 1/17/14 11:44 AM N97099 C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 25 ksmo 1/17/14 5:02 PM N70EF P28R Departure 2749 $ 16.44 26 ksmo 1/17/14 5:03 PM -

UFTAA Congress Kuala Lumpur 2013

UFTAA Congress Kuala Lumpur 2013 Duncan Bureau Senior Vice President Global Sales & Distribution The Airline industry is tough "If I was at Kitty Hawk in 1903 when Orville Wright took off, and would have been farsighted enough, and public-spirited enough -- I owed it to future capitalists -- to shoot them down…” Warren Buffet US Airline Graveyard – A Only AAXICO Airlines (1946 - 1965, to Saturn Airways) Air General Access Air (1998 - 2001) Air Great Lakes ADI Domestic Airlines Air Hawaii (1960s) Aeroamerica (1974 – 1982) Air Hawaii (ceased Operations in 1986) Aero Coach (1983 – 1991) Air Hyannix Aero International Airlines Air Idaho Aeromech Airlines (1951 - 1983, to Wright Airlines) Air Illinois AeroSun International Air Iowa AFS Airlines Airlift International (1946 - 81) Air America (operated by the CIA in SouthEast Asia) Air Kentucky Air America (1980s) Air LA Air Astro Air-Lift Commuter Air Atlanta (1981 - 88) Air Lincoln Air Atlantic Airlines Air Link Airlines Air Bama Air Link Airways Air Berlin, Inc. (1978 – 1990) Air Metro Airborne Express (1946 - 2003, to DHL) Air Miami Air California, later AirCal (1967 - 87, to American) Air Michigan Air Carolina Air Mid-America Air Central (Michigan) Air Midwest Air Central (Oklahoma) Air Missouri Air Chaparral (1980 - 82) Air Molakai (1980) Air Chico Air Molakai (1990) Air Colorado Air Molakai-Tropic Airlines Air Cortez Air Nebraska Air Florida (1972 - 84) Air Nevada Air Gemini Air New England (1975 - 81) US Airline Graveyard – Still A Air New Orleans (1981 – 1988) AirVantage Airways Air -

2012 Silent Auction Items All Values Are Estimated

2012 Silent Auction Items All values are estimated Aircraft Models...............................page 1 Flight and Travel............................ page 6-7 Artwork ..........................................page 1-2 Gifts and More............................... page 7-8 Books.............................................page 2-3 Jewelry & Bling………………..……page 9 Clothing .........................................page 4-5 Training ......................................... page 9-10 Electronics and Equipment............page 5-6 This years raffle items……….……..page 10 Aircraft Models: 73 United Airlines B777 1:100 scale Donated by: United Airlines It’s so nice! Value: $200.00 146 100th anniversary Wright Flyer, silver with gold propellers, 8 11/16” wingspan Donated by: Cindy and Kevin McNeight In the beginning… Value: $60.00 103 Texaco Grumman G21-A amphibian metal bank Donated by: A friend of WAI Saving in style. Value: $70.00 37 UPS B747-400F 1:100 scale Donated by: UPS You really need this. Value: $225.00 124 Airbus A380 1:100 scale Donated by: Airbus Americas, Inc. Keep adding to your collection! Value: $300.00 54 Skywest airlines aircraft model Donated by: Airbus Americas, Inc. Another addition! Value: $25.00 Artwork: 109 #1) Silver framed, antique aviation French postcard Donated by: Cindy Todd Gorgeous Value: $120.00 110 #2) Silver framed, antique aviation Russian postcard Donated by: Cindy Todd Postcards are from Gary Edwards Photography Gallery Value: $120.00 Page 1 of 10 7-10 8- 1954 Charles Hubbell calendar prints 33-34 Donated by: A friend of WAI 56-57 These 8 will be sold separately Value: $10.00 each 24-27 11- 1964 Charles Hubbell calendar prints 45-48 Donated by: A friend of WAI 76-78 These 11 will be sold separately Value: $10.00 each 83 WASP 2008 reunion poster autographed Donated by: A friend of WAI Paving the way for the rest of us. -

CRUCIAL TEST of CAB MERGER POLICY the Railman's Cry Bf "Merge Or Die" May Soon Become the Watchword of the Air Transport Industry

1962] NOTES THE AMERICAN-EASTERN APPLICATION: CRUCIAL TEST OF CAB MERGER POLICY The railman's cry bf "merge or die" may soon become the watchword of the air transport industry. Even though airlines are subject to detailed regulation-to implement safety as well as economic objectives-, including limitations on entry,' price regulation, and in certain cases, federal sub- sidy,2 competition is permitted "to the extent necessary" to ensure a healthy air transport system "adapted to the needs" of commerce, the postal serv- ice, and national defense.3 The United States maintains the world's only competitive airline system, and individual airlines are complaining not about regulation but about regulated competition. 4 In most major markets, there are at least two trunk airlines competing for supremacy and survival, and although the public has benefited from this competition in long-haul markets, service has deteriorated in shoit-haul and intermediate markets as long-haul equipment has become increasingly unsuited for short trips.5 Indeed, the advent of the jet age has set off an equipment race "unparalleled in any transportation system and unlikely to be duplicated." 6 Gains in net income have not kept pace with increases in gross traffic and revenue, and competition from other forms of transportation, particularly the auto- mobile, has become increasingly effective. 7 Because of the effects of the present degree of competition, the problems of equipment financing and low earnings, and the prospect that supersonic transport may magnify these difficulties, both the airlines ard the Civil Aetonautics Board have been considering merger as a possible solution.3 The most recent merger application-that of American and E~tei-n Aiifiesi the second and fourth largest air carriers in the United States- is in many ways unprecedented. -

Controlled Competition: Three Years of the Civil Aeronautics Act Neil G

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 12 | Issue 4 Article 2 1941 Controlled Competition: Three Years of the Civil Aeronautics Act Neil G. Melone Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Neil G. Melone, Controlled Competition: Three Years of the Civil Aeronautics Act, 12 J. Air L. & Com. 318 (1941) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol12/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. CONTROLLED COMPETITION: THREE YEARS OF THE CIVIL AERONAUTICS ACTt NEIL G. MELONE* INTRODUCTION The Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938 was an attempt to remedy a situation in the air transport industry which was characterized as "chaotic" by the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce.' From 1930 to 1934, the entire aviation industry had been dom- inated by three holding companies. 2 As a result of the so-called "spoils conferences" called by Postmaster General Brown in 1930, certain of these groups had secured the bulk of the government's airmail payments. Investigations by the Black Committee had re- vealed the alleged details of the "spoils conferences" and the extent of the interlocking relationships." On the basis of the testimony, Postmaster General Farley had cancelled the contracts in 1934 with- out notice or hearing.4 The experiment of mail flying by army pilots had proved disastrous, and remedy was sought in the Air Mail Act of 1934.5 Mail contracts were to be awarded after competitive bidding, and routes designated by the Postmaster General.6 The Act required the air transport companies to divorce themselves from manufactur- tAdapted from Thesis submitted to Professor Hart in Seminar on Federal Administration at Harvard Law School. -

An Examination of the CAB's Merger Policy

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Articles Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship 1967 An Examination of the CAB's Merger Policy Arthur H. Travers, Jr. University of Colorado Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles Part of the Air and Space Law Commons, Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Transportation Law Commons Citation Information Arthur H. Travers, Jr., An Examination of the CAB's Merger Policy, 15 U. KAN. L. REV. 227 (1967), available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/1145. Copyright Statement Copyright protected. Use of materials from this collection beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission to publish or reproduce is required. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship at Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: Arthur H. Jr. Travers, An Examination of the Cab's Merger Policy, 15 U. Kan. L. Rev. 227, 264 (1967) Provided by: William A. Wise Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Tue Nov 7 17:09:00 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type GINTA GNT 0A Amber Air Lithuania Civil BLUE MESSENGER BMS 0B Blue Air Romania Civil CATOVAIR IBL 0C IBL Aviation Mauritius Civil DARWIN DWT 0D Darwin Airline Switzerland Civil JETCLUB JCS 0J Jetclub Switzerland Civil VASCO AIR VFC 0V Vietnam Air Services Company (VASCO) Vietnam Civil AMADEUS AGT 1A Amadeus IT Group Spain Civil 1B Abacus International Singapore Civil 1C Electronic Data Systems Switzerland Civil 1D Radixx United States Civil 1E Travelsky Technology China Civil 1F INFINI Travel Information Japan Civil 1G Galileo International United States Civil 1H Siren-Travel Russia Civil CIVIL AIR AMBULANCE AMB 1I Deutsche Rettungsflugwacht Germany Civil EXECJET EJA 1I NetJets United States Civil FRACTION NJE 1I NetJets Europe Portugal Civil NAVIGATOR NVR 1I Novair Sweden Civil PHAZER PZR 1I Sky Trek International Airlines United States Civil Sunturk 1I Pegasus Hava Tasimaciligi Turkey Civil 1I Sierra Nevada Airlines United States Civil 1K Southern Cross Distribution Australia Civil 1K Sutra United States Civil OPEN SKIES OSY 1L Open Skies Consultative Commission United States Civil -

Air Transport

National Air & Space Museum Technical Reference Files: Air Transport NASM Staff 2017 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 2 Series F0: Air Transport, General............................................................................ 2 Series F1: Air Transport, Airlines........................................................................... 23 Series F2: Air Transport, by Region or Nation..................................................... 182 Series F3: Air Transport, Airports, General.......................................................... 189 Series F4: Air Transport, Airports, USA............................................................... 198 Series F5: Air Transport, Airports, Foreign.......................................................... 236 Series F6: Air Transport, Air Mail......................................................................... 251 National Air & Space Museum Technical Reference Files: Air Transport NASM.XXXX.1183.F Collection Overview Repository: National Air and Space Museum Archives Title: National -

Directory of New England In-House Counsel

DIRECTORY OF 2021 BREAK THROUGH WITH BOWDITCH Whether you’re reinventing your organization or disrupting your entire industry, rely on a team of attorneys who see the world your way. At Bowditch, we’ll help you craft your business and legal strategy and manage the essential details so you can stay focused on your long-term vision. Visit bowditch.com for legal insights and analysis Letter from the Publisher WELCOME TO THE 2020-2021 DIRECTORY OF NEW ENGLAND IN-HOUSE COUNSEL We are proud to provide you with the most comprehensive catalog of its kind, and we hope you find it to be a valuable reference tool. Lawyers Weekly is committed to serving corporate counsel throughout the region, and this year’s edition has been extensively reviewed for accuracy and completeness. Our goal is to enhance your access to in-house attorneys throughout New England. New England In-House, our quarterly publication, provides the news and information corporate counsel need in their practices. Please visit www.newenglandinhouse.com to register for a complimentary subscription. I encourage you to contact me at [email protected] with any suggestions and comments on how to improve the Directory of New England In-House Counsel. Additionally, if any updates are required for your company’s listing, please use the correction form below, or email us at [email protected]. In case you didn’t already know, corporate attorneys can find a wealth of information every day on Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly’s website, masslawyersweekly.com, and on Rhode Island Lawyers Weekly’s website, rilawyersweekly.com.