Notes on the History of Federal Regulation of Airline Mergers Lucie Sheppard Keyes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2013 Air Line Pilot 1 @Wearealpa PRINTED in the U.S.A

Protecting Our Future Page 20 Follow us on Twitter September 2013 Air Line Pilot 1 @wearealpa PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. PRINTED IN SEPTEMBER 2013 • VoluME 82, NuMBER 9 17 24 20 About the Cover A Delta B-757 landing at COMMENTARY Minneapolis–St. Paul International 4 Take Note Airport. Photo by Complete the Pass 28 The Capt. Eric Cowan (Compass). 5 Aviation Matters Military Download a QR Lifelong Lessons Channel: reader to your smartphone, scan the code, and 6 Weighing In limited read the magazine. Prepared for the Future but 30 Air Line Pilot (ISSN 0002-242X) is pub lished Reemerging monthly by the Air Line Pilots Association, Inter national, affiliated with AFL-CIO, SPECIAL SECTION Resource CLC. Editorial Offices: 535 Herndon 34 AlPA Represents Parkway, PO Box 1169, Herndon, VA 20 Building the for Airline Pilot 20172-1169. Telephone: 703-481-4460. Communications Fax: 703-464-2114. Copyright © 2013—Air Airline Piloting Recruitment Line Pilots Association, Inter national, all rights reserved. Publica tion in any form Profession for the 29 Community 36 our Stories without permission is prohibited. Air Line Braniff Pilot Refuses to Take Pilot and the ALPA logo Reg. U.S. Pat. Future outreach to Primary and T.M. Office. Federal I.D. 36-0710830. Retirement Sitting Down Periodicals postage paid at Herndon, VA 22 Mentoring a New and Secondary 20172, and additional offices. Schools 37 The landing Postmaster: Send address changes to Generation of Airline Air Line Pilot, PO Box 1169, Herndon, VA Pilots How Does Your University 20172-1169. Rank? Canadian Publications Mail Agreement DEPARTMENTS #40620579: Return undeliverable maga- 24 Auburn’s Flight zines sent to Canadian addresses to 2835 Kew Drive, Windsor, ON, Canada N8T 3B7. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Airline Service Abandonment and Consolidation - a Chapter in the Battle Ga Ainst Subsidization Ronald D

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Southern Methodist University Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 32 | Issue 4 Article 2 1966 Airline Service Abandonment and Consolidation - A Chapter in the Battle ga ainst Subsidization Ronald D. Dockser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Ronald D. Dockser, Airline Service Abandonment and Consolidation - A Chapter in the Battle against Subsidization, 32 J. Air L. & Com. 496 (1966) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol32/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. AIRLINE SERVICE ABANDONMENT AND CONSOLIDATION - A CHAPTER IN THE BATTLE AGAINST SUBSIDIZATIONt By RONALD D. DOCKSERtt CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION II. THE CASE FOR ELIMINATING SUBSIDY A. Subsidy Cost B. Misallocation Results Of Subsidy C. CAB Present And Future Subsidy Goals III. PROPOSALS FOR FURTHER SUBSIDY REDUCTION A. Federal TransportationBill B. The Locals' Proposal C. The Competitive Solution 1. Third Level Carriers D. Summary Of Proposals IV. TRUNKLINE ROUTE ABANDONMENT A. Passenger Convenience And Community Welfare B. Elimination Of Losses C. Equipment Modernization Program D. Effect On Competing Carriers E. Transfer Of Certificate Approach F. Evaluation Of Trunkline Abandonment V. LOCAL AIRLINE ROUTE ABANDONMENT A. Use-It-Or-Lose-It 1. Unusual and Compelling Circumstances a. Isolation and Poor Surface Transportation b. -

This Is Our Largest Issue Ever at 24 Pages As We Celebrate the 5 Th an N Iversary of Our N Ewsletter

1 SUMMER 2005 ISSUE # 20 This is our largest issue ever at 24 pages as we celebrate the 5 th an n iversary of our n ewsletter. It started with the F all 20 0 0 issue of 8 pages af ter the id ea was born at the 20 0 0 F Y V - F S M R eun ion . A collection was tak en up that d ay to laun ch F R O N TIE R N E W S . It has been on e of the m ost reward in g ex peri- en ces of m y lif e. M y heartf elt than k s to all of y ou who have helped m ak e it possible. S pecial than k s to K en L ean d er (station agen t at H U T S L N S E A IC T) who sen t 1 0 6 F L m agaz in es. They are a gold m in e of F L his- tory . K en S chultz an d C al R eese sen t pack ets of photos an d (Continued on page 2) 2 The FRONTIER NEWS is published quarterly and dedicated to ex-employees, friends, family and fans of the “old” Frontier Airlines TIMETABLE which “died” on August 24, 1986 and was “buried” on May 31, 1990. This is the information we currently have. Coordinators of It is a non-profit operation. All income goes into keeping the NEWS FL events, please let us know the details so we can post it. -

Arizona Transportation History

Arizona Transportation History Final Report 660 December 2011 Arizona Department of Transportation Research Center DISCLAIMER The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Arizona Department of Transportation or the Federal Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Trade or manufacturers' names which may appear herein are cited only because they are considered essential to the objectives of the report. The U.S. Government and the State of Arizona do not endorse products or manufacturers. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA-AZ-11-660 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date December 2011 ARIZONA TRANSPORTATION HISTORY 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author 8. Performing Organization Report No. Mark E. Pry, Ph.D. and Fred Andersen 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. History Plus 315 E. Balboa Dr. 11. Contract or Grant No. Tempe, AZ 85282 SPR-PL-1(173)-655 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13.Type of Report & Period Covered ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 206 S. 17TH AVENUE PHOENIX, ARIZONA 85007 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Project Manager: Steven Rost, Ph.D. 15. Supplementary Notes Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration 16. Abstract The Arizona transportation history project was conceived in anticipation of Arizona’s centennial, which will be celebrated in 2012. Following approval of the Arizona Centennial Plan in 2007, the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT) recognized that the centennial celebration would present an opportunity to inform Arizonans of the crucial role that transportation has played in the growth and development of the state. -

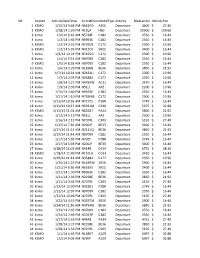

Rslt Airport Activitydatetime Aircraftnummodeltypeactivity

rslt Airport ActivityDateTime AircraftNumModelTypeActivity MaxLandin ActivityFee 1 KSMO 1/10/14 9:43 PM N661PD AS50 Departure 4600 $ 27.40 2 KSMO 1/18/14 1:20 PM N15LA H60 Departure 20000 $ 109.60 3 ksmo 1/2/14 9:16 AM N5738F C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 4 ksmo 1/2/14 1:43 PM N9955E C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 5 KSMO 1/2/14 3:52 PM N739DZ C172 Departure 2300 $ 10.96 6 KSMO 1/2/14 5:03 PM N412DJ SR22 Departure 3400 $ 16.44 7 ksmo 1/3/14 12:24 PM N7425G C172 Departure 2300 $ 10.96 8 ksmo 1/4/14 9:51 AM N97099 C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 9 KSMO 1/5/14 8:28 AM N97099 C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 10 ksmo 1/6/14 2:29 PM N18308 BE36 Departure 3850 $ 21.92 11 ksmo 1/7/14 10:24 AM N2434U C172 Departure 2300 $ 10.96 12 ksmo 1/7/14 2:33 PM N35884 C177 Departure 2350 $ 10.96 13 ksmo 1/8/14 1:21 PM N4792W AC11 Departure 3140 $ 16.44 14 ksmo 1/9/14 2:33 PM N51LL AA5 Departure 2200 $ 10.96 15 ksmo 1/10/14 2:40 PM N9955E C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 16 ksmo 1/11/14 1:10 PM N739MB C172 Departure 2300 $ 10.96 17 ksmo 1/13/14 10:26 AM N727CS P28R Departure 2749 $ 16.44 18 ksmo 1/13/14 10:27 AM N5931M C340 Departure 5975 $ 32.88 19 KSMO 1/13/14 11:01 AM N8328T PA44 Departure 3800 $ 21.92 20 ksmo 1/13/14 5:13 PM N51LL AA5 Departure 2200 $ 10.96 21 ksmo 1/16/14 2:12 PM N707RL C303 Departure 5150 $ 27.40 22 ksmo 1/17/14 7:36 AM N200JF BE33 Departure 3400 $ 16.44 23 ksmo 1/17/14 11:13 AM N2111Q BE36 Departure 3850 $ 21.92 24 ksmo 1/17/14 11:44 AM N97099 C182 Departure 2550 $ 16.44 25 ksmo 1/17/14 5:02 PM N70EF P28R Departure 2749 $ 16.44 26 ksmo 1/17/14 5:03 PM -

FL Chronology20-11-23.Wps

A CHRONOLOGY OF OLD FRONTIER AIRLINES AND ITS PREDECESSORS 1938 1/24 Ray Wilson Inc. incorporated in Colorado 1939 Unk Ray Wilson filed for an airline operating certificate 1941 Dec. Charles Hirsig becomes president of Summit Airways 1942 Sep. Rocky Nelson becomes Arizona Airways’ only president 1945 1/15 Charles Hirsig, founder of Summit Airways-beginning of Challenger Airlines, dies at age 34 1945 9/17 Arizona Corp. comm. authorized 1946 3/17 Arizona Airways inaugurates intrastate service, crew Moore, Lowe, Conger - steward 1946 3/28 C.A.B. certificate issued to Ray Wilson, Inc 1946 3/28 C.A.B. certificate issued to Summit Airways 1946 7/2 Ray Wilson Inc. renamed Monarch Airlines Inc. 1946 8/21 C.A.B. certificate for Wilson reissued and renamed as Monarch Airlines 1946 9/30 Monarch’s first DC-3 arrives in DEN - SN64422 1946 11/14 C.A.B. certificate issued to Central Airlines 1946 11/26 Operating certificate issued to Monarch Airlines 1946 11/27 Monarch's first scheduled flight DEN COS PUB CNE MVS DRO but unable to land at CNE and DRO due to muddy field conditions, crew was Capt. Art Ashworth, FO Ray Harvey & Steward Vern Carlson and carried one passenger 1946 11/30 Monarch first flight DEN-DRO 1947 Jan. George Snyder becomes president of Challenger Airlines 1947 1/17 Service to GJT started, Monarch starts FMN-ABQ service 1947 2/10 Hal Darr takes over Monarch as president, other sources say it was Mar 1947 1947 3/21 C.A.B. certficate for Summit reissued and renamed as Challenger Airlines 1947 May. -

Summer 2001 Vol. 1 Issue 4 Another

1 SUMMER 2001 VOL. 1 ISSUE 4 HISTORY ANOTHER LOOK AT WHAT SIGNIFICANT Frontier Airlines was offi- CHANGES cially born on June 1, 1950 KILLED FRONTIER In 1978, the Airline Deregula- resulting from the merger of by Dena Andrews, et al tion Act brought about a dramatic Monarch Air Lines, Challenger change in the industry such that Airlines and Arizona Airways. airlines could expand their routes simply by giving a ninety-day The new company’s home base was in Denver, Colorado servic- notice. This environment encouraged fierce competition among ing the Pacific Southwest Region. During the 1950’s new routes some carriers fighting to dominate the Denver hub. Between were added to their distribution network, as well as new 44- this period and 1982, Frontier dropped 39 routes from their passenger Convair 340 aircraft to serve most of Frontier’s network and added 29 new cities with further emphasis placed system. on their Denver hub. In the 60’s the company introduced a special fare plan called Given the changing environment, Frontier placed additional “21” to cut the cost of travel, resulting in a 26% percent increase attention on restructuring and gaining a competitive edge needed in passengers enplaned. All time records were experienced in in a deregulated market. Mr. Lowell Shirley, who had worked 1963 with passenger boarding up 44% and growth exceeding all with Frontier’s data processing system in the past, was recruited other 23 regional airlines in the United States. Frontier later in 1981 to help Frontier achieve its objectives. In 1983, Lowell became the technical leader by acquiring jet power aircraft Shirley restructured management’s goals and drew up four com- including the Boeing 727 and 737, along with being the first to mitments: introduce a computerized reservation system. -

UFTAA Congress Kuala Lumpur 2013

UFTAA Congress Kuala Lumpur 2013 Duncan Bureau Senior Vice President Global Sales & Distribution The Airline industry is tough "If I was at Kitty Hawk in 1903 when Orville Wright took off, and would have been farsighted enough, and public-spirited enough -- I owed it to future capitalists -- to shoot them down…” Warren Buffet US Airline Graveyard – A Only AAXICO Airlines (1946 - 1965, to Saturn Airways) Air General Access Air (1998 - 2001) Air Great Lakes ADI Domestic Airlines Air Hawaii (1960s) Aeroamerica (1974 – 1982) Air Hawaii (ceased Operations in 1986) Aero Coach (1983 – 1991) Air Hyannix Aero International Airlines Air Idaho Aeromech Airlines (1951 - 1983, to Wright Airlines) Air Illinois AeroSun International Air Iowa AFS Airlines Airlift International (1946 - 81) Air America (operated by the CIA in SouthEast Asia) Air Kentucky Air America (1980s) Air LA Air Astro Air-Lift Commuter Air Atlanta (1981 - 88) Air Lincoln Air Atlantic Airlines Air Link Airlines Air Bama Air Link Airways Air Berlin, Inc. (1978 – 1990) Air Metro Airborne Express (1946 - 2003, to DHL) Air Miami Air California, later AirCal (1967 - 87, to American) Air Michigan Air Carolina Air Mid-America Air Central (Michigan) Air Midwest Air Central (Oklahoma) Air Missouri Air Chaparral (1980 - 82) Air Molakai (1980) Air Chico Air Molakai (1990) Air Colorado Air Molakai-Tropic Airlines Air Cortez Air Nebraska Air Florida (1972 - 84) Air Nevada Air Gemini Air New England (1975 - 81) US Airline Graveyard – Still A Air New Orleans (1981 – 1988) AirVantage Airways Air -

An Inside Look at the Death of Frontier Airlines La Rry Va Nno Ymu Rd Ered in a Riz O Na

1 WINTER 2001 Welcom e To The 21st Century V olum e 1 Issue 2 employees it would mean a public relations coup of the century AN INSIDE LOOK AT THE for Continental. I further agreed that the strike was over, that he had won, that it was time to put all that behind us and together DEATH OF fight the real enemy. Dick Ferris and United Airlines! Lorenzo stated he felt good about our conversation and that FR ONTIER AIR LINES the Frontier Captains should keep their seats if something was to work out. I stated that the earlier letter sent to Burr threatening by Captain Billy Walker (Part 2) dire consequences if he dared consider a merger with Lorenzo In ALPA's defense, Duffy could have done little with the way be ignored. I wanted to see all of our pilots receive a fair and the Airline Pilots Association is structured with MEC autonomy. equitable integration. Certainly, with Roger Hall’s continued reassurances ALPA na- While Lorenzo made no further commitments he left me with tional could do little more than pressure the UAL MEC. a sense of promise. Amazing, here I was asking the very man, I The following day, one year ago today, August 28th, 1986 the had joined to fight against ever owning Frontier, for a job and to UAL MEC listened to my appeal, turned their brotherly backs, buy him dinner. Steak, no less. and have ignored the plight of the Frontier family to this day. Shortly, we were involved with the Prince of Darkness, John Certainly, there were concerned UAL individuals expressing Adams, Vice President Human Resources, Continental Airlines their dismay. -

2012 Silent Auction Items All Values Are Estimated

2012 Silent Auction Items All values are estimated Aircraft Models...............................page 1 Flight and Travel............................ page 6-7 Artwork ..........................................page 1-2 Gifts and More............................... page 7-8 Books.............................................page 2-3 Jewelry & Bling………………..……page 9 Clothing .........................................page 4-5 Training ......................................... page 9-10 Electronics and Equipment............page 5-6 This years raffle items……….……..page 10 Aircraft Models: 73 United Airlines B777 1:100 scale Donated by: United Airlines It’s so nice! Value: $200.00 146 100th anniversary Wright Flyer, silver with gold propellers, 8 11/16” wingspan Donated by: Cindy and Kevin McNeight In the beginning… Value: $60.00 103 Texaco Grumman G21-A amphibian metal bank Donated by: A friend of WAI Saving in style. Value: $70.00 37 UPS B747-400F 1:100 scale Donated by: UPS You really need this. Value: $225.00 124 Airbus A380 1:100 scale Donated by: Airbus Americas, Inc. Keep adding to your collection! Value: $300.00 54 Skywest airlines aircraft model Donated by: Airbus Americas, Inc. Another addition! Value: $25.00 Artwork: 109 #1) Silver framed, antique aviation French postcard Donated by: Cindy Todd Gorgeous Value: $120.00 110 #2) Silver framed, antique aviation Russian postcard Donated by: Cindy Todd Postcards are from Gary Edwards Photography Gallery Value: $120.00 Page 1 of 10 7-10 8- 1954 Charles Hubbell calendar prints 33-34 Donated by: A friend of WAI 56-57 These 8 will be sold separately Value: $10.00 each 24-27 11- 1964 Charles Hubbell calendar prints 45-48 Donated by: A friend of WAI 76-78 These 11 will be sold separately Value: $10.00 each 83 WASP 2008 reunion poster autographed Donated by: A friend of WAI Paving the way for the rest of us.