PCR: Bangladesh: Northwest Crop Diversification Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nawab Siraj-Ud-Dowla Govt. College Higher Secondary Shift : Day , Medium : Bangla Class : Xi-Science, Department : Science Session :2020-2021

Nawab Siraj-Ud-Dowla Govt. College Higher Secondary Shift : Day , Medium : Bangla Class : Xi-science, Department : Science Session :2020-2021 SL. Std. Code Std. Name Std. Father Name Mother Name D.O.B Religion Roll Session Gd. Mobile Present Address Permanent Address Blood Father NID Mother NID Father Father Occ. Image Name(BN) No. Group Income 1 200010001 Md. Al-amin Md. Alauddin Mst. Lipiara 2003- Islam 2014011001 2020- 01729468039 Vill: Banshbaria, Post: Banshbaria, P/s: Bagatipara, Vill: Banshbaria, Post: Banshbaria, P/s: Bagatipara, B+ 2836233557 6910976631903 70000 Private 200010001.jpg Begum 10-02 2021 Dist: Natore. Dist: Natore. Service 2 200010002 Jahid Hasan জািহদ হাসান Md. Nizam Mst. Morzina 2003- Islam 2014011002 2020- 01311967961 Vill- Gopalpur, Post- Gormati, Ps- Boraigram, Dist- Vill- Gopalpur, Post- Gormati, Ps- Boraigram, Dist- Ab+ N/a 6911535201097 60000 Farmer 200010002.jpg Pramanik ামািনক Pramanik Khatun 06-15 2021 Natore. Natore. 3 200010003 Md. Tanvir মাঃ তানভীর Md. Subahan Mst. Rehena 2003- Islam 2014011003 2020- 01710438685 Vill. North Muradpur. Post. Luxmanhati Ps. Vill. North Muradpur. Post. Luxmanhati Ps. B+ 329 035 8997 689 032 5027 60000 Farmer 200010003.jpg Ahmed আহেমদ Ali Begum 03-10 2021 Bagatipara. Zeela. Natore Bagatipara. Zeela. Natore 4 200010004 Md. Akhibul মাঃ আিখবুল Md. Rofikul Mst. Ambia 2004- Islam 2014011004 2020- 01761652477 Vill: Kanaipara, Post: Jewpara, P/s: Puthia, Dist: Vill: Kanaipara, Post: Jewpara, P/s: Puthia, Dist: O+ 8118254698307 8118254698300 60000 Business 200010004.jpg Islam Lam ইসলাম লাম Islam Begum 07-01 2021 Rajshahi. Rajshahi. 5 200010005 Mynul Islam মাইনুল Nurul Islam Kohinoor 2003- Islam 2014011005 2020- 01726324812 Vill: Uttar Potuapara, Post: Natore, Upazila: Natore Vill: Uttar Potuapara, Post: Natore, Upazila: Natore A+ 3295269272 3295503431 100000 Business 200010005.jpg Mohin ইসলাম মিহন Begum 07-05 2021 Sadar, Dist: Natore. -

CPD-CMI Working Paper Series Finance for Local Government in Bangladesh an Elusive Agenda 6

CPD-CMI Working Paper Series 6 Finance for Local Government in Bangladesh An Elusive Agenda Debapriya Bhattacharya Mobasser Monem Umme Shefa Rezbana CENTRE FOR POLICY DIALOGUE (CPD) B A N G L A D E S H a c i v i l s o c i e t y t h i n k t a n k Absorbing Innovative Financial Flows: Looking at Asia FINANCE FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN BANGLADESH An Elusive Agenda CPD-CMI Working Paper 6 Debapriya Bhattacharya Mobasser Monem Umme Shefa Rezbana Dr Debapriya Bhattacharya is a Distinguished Fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD); Dr Mobasser Monem is Professor, Department of Public Administration, University of Dhaka and Ms Umme Shefa Rezbana is Research Associate, CPD. i CPD Working Paper 000 Publishers Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) House 40C, Road 32, Dhanmondi R/A Dhaka 1209, Bangladesh Telephone: (+88 02) 8124770, 9126402, 9141703, 9141734 Fax: (+88 02) 8130951; E-mail: [email protected] Website: cpd.org.bd Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) Jekteviksbakken 31, 5006 Bergen, Norway P.O. Box 6033 Bedriftssenteret, N-5892 Bergen, Norway Telephone: (+47 47) 93 80 00; Fax: (+47 47) 93 80 01 E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.cmi.no First Published November 2013 © Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of CPD or CMI. Tk. 90 USD 6 ISSN 2225-8175 (Online) ISSN 2225-8035 (Print) Cover Design Avra Bhattacharjee CCM42013_3WP6_DGP ii Absorbing Innovative Financial Flows: Looking at Asia The present Working Paper Series emerged from a joint collaborative programme being implemented by the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), Dhaka, Bangladesh and the Chr. -

Esdo Profile 2021

ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) ESDO PROFILE 2021 Head Office Address: Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) Collegepara (Gobindanagar), Thakurgaon-5100, Thakurgaon, Bangladesh Phone:+88-0561-52149, +88-0561-61614 Fax: +88-0561-61599 Mobile: +88-01714-063360, +88-01713-149350 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Dhaka Office: ESDO House House # 748, Road No: 08, Baitul Aman Housing Society, Adabar,Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-58154857, Mobile: +88-01713149259, Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd 1 ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) 1. BACKGROUND Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) has started its journey in 1988 with a noble vision to stand in solidarity with the poor and marginalized people. Being a peoples' centered organization, we envisioned for a society which will be free from inequality and injustice, a society where no child will cry from hunger and no life will be ruined by poverty. Over the last thirty years of relentless efforts to make this happen, we have embraced new grounds and opened up new horizons to facilitate the disadvantaged and vulnerable people to bring meaningful and lasting changes in their lives. During this long span, we have adapted with the changing situation and provided the most time-bound effective services especially to the poor and disadvantaged people. Taking into account the government development policies, we are currently implementing a considerable number of projects and programs including micro-finance program through a community focused and people centered approach to accomplish government’s development agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN as a whole. -

State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance Among the Santal in Bangladesh

The Issue of Identity: State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance among the Santal in Bangladesh PhD Dissertation to attain the title of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Submitted to the Faculty of Philosophische Fakultät I: Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften Institut für Ethnologie und Philosophie Seminar für Ethnologie Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg This thesis presented and defended in public on 21 January 2020 at 13.00 hours By Farhat Jahan February 2020 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Reviewers: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Assessment Committee: Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Prof. Dr. Kirsten Endres Prof. Dr. Rahul Peter Das To my parents Noor Afshan Khatoon and Ghulam Hossain Siddiqui Who transitioned from this earth but taught me to find treasure in the trivial matters of life. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to trace transformations among the Santal of Bangladesh. To scrutinize these transformations, the hegemonic power exercised over the Santal and their struggle to construct a Santal identity are comprehensively examined in this thesis. The research locations were multi-sited and employed qualitative methodology based on fifteen months of ethnographic research in 2014 and 2015 among the Santal, one of the indigenous groups living in the plains of north-west Bangladesh. To speculate over the transitions among the Santal, this thesis investigates the impact of external forces upon them, which includes the epochal events of colonization and decolonization, and profound correlated effects from evangelization or proselytization. The later emergence of the nationalist state of Bangladesh contained a legacy of hegemony allowing the Santal to continue to be dominated. -

Underground Stone Collection and Its Impact on Environment: a Study on Panchagarh District

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol.10 Issue 08, August 2020, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gate as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Underground Stone Collection and Its Impact on Environment: A Study on Panchagarh District Md. Forhad Ahmmed, PhD1 Abstract: In most countries of the world, underground mining resources are considered as important contributors to economic development. But quite often these works cause a lot of damage to the environment and put many lives under threat. In the northern part of Bangladesh, there are huge quantities of stones stored beneath the surface in some districts. Local people collect these stone and supply them to different places for construction and development work. The researcher chose this important area of study to explore the environmental impact of underground stone collection. The study was an exploratory one based on sample survey, where the researcher tried to show the environmental impact of underground stone collection. The study conducted in the farthest district of Bangladesh- Panchagarh. The researcher collected data from four categories of respondent. A total of 317 respondents were considered as the sample of the study. It is observed from the findings of the study that though due to stone collection the socio-economic condition of the local people had developed, it has left some negative impacts on environment of the study area. -

List of 100 Bed Hospital

List of 100 Bed Hospital No. of Sl.No. Organization Name Division District Upazila Bed 1 Barguna District Hospital Barisal Barguna Barguna Sadar 100 2 Barisal General Hospital Barisal Barishal Barisal Sadar (kotwali) 100 3 Bhola District Hospital Barisal Bhola Bhola Sadar 100 4 Jhalokathi District Hospital Barisal Jhalokati Jhalokati Sadar 100 5 Pirojpur District Hospital Barisal Pirojpur Pirojpur Sadar 100 6 Bandarban District Hospital Chittagong Bandarban Bandarban Sadar 100 7 Comilla General Hospital Chittagong Cumilla Comilla Adarsha Sadar 100 8 Khagrachari District Hospital Chittagong Khagrachhari Khagrachhari Sadar 100 9 Lakshmipur District Hospital Chittagong Lakshmipur Lakshmipur Sadar 100 10 Rangamati General Hospital Chittagong Rangamati Rangamati Sadar Up 100 11 Faridpur General Hospital Dhaka Faridpur Faridpur Sadar 100 12 Madaripur District Hospital Dhaka Madaripur Madaripur Sadar 100 13 Narayanganj General (Victoria) Hospital Dhaka Narayanganj Narayanganj Sadar 100 14 Narsingdi District Hospital Dhaka Narsingdi Narsingdi Sadar 100 15 Rajbari District Hospital Dhaka Rajbari Rajbari Sadar 100 16 Shariatpur District Hospital Dhaka Shariatpur Shariatpur Sadar 100 17 Bagerhat District Hospital Khulna Bagerhat Bagerhat Sadar 100 18 Chuadanga District Hospital Khulna Chuadanga Chuadanga Sadar 100 19 Jhenaidah District Hospital Khulna Jhenaidah Jhenaidah Sadar 100 20 Narail District Hospital Khulna Narail Narail Sadar 100 21 Satkhira District Hospital Khulna Satkhira Satkhira Sadar 100 22 Netrokona District Hospital Mymensingh Netrakona -

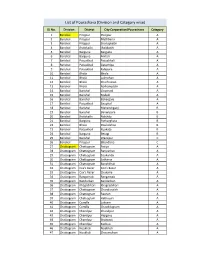

List of Pourashava (Division and Category Wise)

List of Pourashava (Division and Category wise) SL No. Division District City Corporation/Pourashava Category 1 Barishal Pirojpur Pirojpur A 2 Barishal Pirojpur Mathbaria A 3 Barishal Pirojpur Shorupkathi A 4 Barishal Jhalokathi Jhalakathi A 5 Barishal Barguna Barguna A 6 Barishal Barguna Amtali A 7 Barishal Patuakhali Patuakhali A 8 Barishal Patuakhali Galachipa A 9 Barishal Patuakhali Kalapara A 10 Barishal Bhola Bhola A 11 Barishal Bhola Lalmohan A 12 Barishal Bhola Charfession A 13 Barishal Bhola Borhanuddin A 14 Barishal Barishal Gournadi A 15 Barishal Barishal Muladi A 16 Barishal Barishal Bakerganj A 17 Barishal Patuakhali Bauphal A 18 Barishal Barishal Mehendiganj B 19 Barishal Barishal Banaripara B 20 Barishal Jhalokathi Nalchity B 21 Barishal Barguna Patharghata B 22 Barishal Bhola Doulatkhan B 23 Barishal Patuakhali Kuakata B 24 Barishal Barguna Betagi B 25 Barishal Barishal Wazirpur C 26 Barishal Pirojpur Bhandaria C 27 Chattogram Chattogram Patiya A 28 Chattogram Chattogram Bariyarhat A 29 Chattogram Chattogram Sitakunda A 30 Chattogram Chattogram Satkania A 31 Chattogram Chattogram Banshkhali A 32 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Cox’s Bazar A 33 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Chakaria A 34 Chattogram Rangamati Rangamati A 35 Chattogram Bandarban Bandarban A 36 Chattogram Khagrchhari Khagrachhari A 37 Chattogram Chattogram Chandanaish A 38 Chattogram Chattogram Raozan A 39 Chattogram Chattogram Hathazari A 40 Chattogram Cumilla Laksam A 41 Chattogram Cumilla Chauddagram A 42 Chattogram Chandpur Chandpur A 43 Chattogram Chandpur Hajiganj A -

1 Small Area Estimation of Poverty in Rural

1 Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Economics, XL 1&2 (2019): 1-16 SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF POVERTY IN RURAL BANGLADESH Md. Farouq Imam1 Mohammad Amirul Islam1 Md. Akhtarul Alam1* Md. Jamal Hossain1 Sumonkanti Das2 ABSTRACT Poverty is a complex phenomenon and most of the developing countries are struggling to overcome the problem. Small area estimation offers help to allocate resources efficiently to address poverty at lower administrative level. This study used data from Census 2011 and Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES)-2010. Using ELL and M-Quantile methods, this study identified Rangpur division as the poorest one where Kurigram is the poorest district. Finally, considering both upper and lower poverty lines this study identified the poverty estimates at upazila level of Rangpur division using ELL and M-Quantile methods. The analyses found that 32% of the households were absolute poor and 19% were extremely poor in rural Bangladesh. Among the upazilas under Rangpur division Rajarhat, Ulipur, Char Rajibpur, Phulbari, Chilmari, Kurigram Sadar, Nageshwari, and Fulchhari Upazilas have been identified as the poorest upazilas. Keywords: Small area, poverty, ELL, M-Quantile methods I. INTRODUCTION Bangladesh is a developing country in the south Asia. According to the recent statistics by Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS, 2017, HIES, 2010) the per capita annual income of Bangladesh is US$1610, estimated Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is 7.28, and the percentage below the poverty line (upper) is 24.30 percent. The population is predominantly rural, with about 70 percent people living in rural areas (HIES, 2016). In Bangladesh, poverty scenario was first surveyed in 1973-1974. -

Impacts of Northwest Fisheries Extension Project (NFEP) on Pond Fish Farming in Improving Livelihood Approach

J. Bangladesh Agril. Univ. 8(2): 305–311, 2010 ISSN 1810-3030 Impacts of Northwest Fisheries Extension Project (NFEP) on pond fish farming in improving livelihood approach M. R. Islam1 and M. R. Haque2 1Department of Fisheries Biology and Genetics, 2Department of Fisheries Management, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh Abstract Investigation was carried out from June to August 2009. A total of 40 fish farmers were selected from northwest two upazila namely Debigonj (n=20) and Boda (n=20) where both men and women were targeted. Focus group discussion (FGD) and cross-check interview were conducted to get an overview on carp farming. From 1991-1995, 1996-2000 and after 2000; 17.5%, 45% and 37.5% of fish farmers started carp farming respectively. Average 77.5% of farmers acquired training from NFEP project while 10% of them from government officials. There were 55% seasonal and 45% perennial ponds with average pond size 0.09 ha. After phase out of NFEP project, 92.5% of fish farmers followed polyculture systems, while only 7.5% of them followed monoculture ones. Farmers did not use any lime, organic and inorganic fertilizers in their ponds before association with NFEP project. They used lime, cow dung, urea and T.S.P during pond preparation at the rate of 247, 2562.68, 46.36 and 27.29 kg.ha-1.y-1 respectively where stocking density at the rate of 10,775 fry.ha-1 after phase out of the project. Feeding was at the rate of 3-5% body weight.fish-1.day-1. -

Social Safeguards Due Diligence Report

Rural Connectivity Improvement Project (RRP BAN 47243) Social Safeguards Due Diligence Report Project number: 47243-004 June 2018 People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Rural Connectivity Improvement Project Prepared by Local Government Engineering Department (LGED), Local Government Division (LGD), Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives (MLGRD&C), Government of The People’s Republic of Bangladeshfor the Asian Development Bank. This social safeguard due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. 1 Table of Contents Page ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF ANNEXURE ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1 - Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1. Project Description ........................................................................................................................ -

List of Madrsha

List of Madrasha Division BARISAL District BARGUNA Thana AMTALI Sl Eiin Name Village/Road Mobile 1 100065 WEST CHILA AMINIA FAZIL MADRASAH WEST CHILA 01716835134 2 100067 MOHAMMADPUR MAHMUDIA DAKHIL MADRASAH MOHAMMADPUR 01710322701 3 100069 AMTALI BONDER HOSAINIA FAZIL MADRASHA AMTALI 01714599363 4 100070 GAZIPUR SENIOR FAZIL (B.A) MADRASHA GAZIPUR 01724940868 5 100071 KUTUBPUR FAZIL MADRASHA KRISHNA NAGAR 01715940924 6 100072 UTTAR KALAMPUR HATEMMIA DAKHIL MADRASA KAMALPUR 01719661315 7 100073 ISLAMPUR HASHANIA DAKHIL MADRASHA ISLAMPUR 01745566345 8 100074 MOHISHKATA NESARIA DAKHIL MADRASA MOHISHKATA 01721375780 9 100075 MADHYA TARIKATA DAKHIL MADRASA MADHYA TARIKATA 01726195017 10 100076 DAKKHIN TAKTA BUNIA RAHMIA DAKHIL MADRASA DAKKHIN TAKTA BUNIA 01718792932 11 100077 GULISHAKHALI DAKHIL MDRASHA GULISHAKHALI 01706231342 12 100078 BALIATALI CHARAKGACHHIA DAKHIL MADRASHA BALIATALI 01711079989 13 100080 UTTAR KATHALIA DAKHIL MADRASAH KATHALIA 01745425702 14 100082 PURBA KEWABUNIA AKBARIA DAKHIL MADRASAH PURBA KEWABUNIA 01736912435 15 100084 TEPURA AHMADIA DAKHIL MADRASA TEPURA 01721431769 16 100085 AMRAGACHIA SHALEHIA DAKHIL AMDRASAH AMRAGACHIA 01724060685 17 100086 RAHMATPUR DAKHIL MADRASAH RAHAMTPUR 01791635674 18 100088 PURBA PATAKATA MEHER ALI SENIOR MADRASHA PATAKATA 01718830888 19 100090 GHOP KHALI AL-AMIN DAKHIL MADRASAH GHOPKHALI 01734040555 20 100091 UTTAR TEPURA ALAHAI DAKHIL MADRASA UTTAR TEPURA 01710020035 21 100094 GHATKHALI AMINUDDIN GIRLS ALIM MADRASHA GHATKHALI 01712982459 22 100095 HARIDRABARIA D.S. DAKHIL MADRASHA HARIDRABARIA -

Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh E-Tender Notice

Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Office of the Project Director Construction of District Relief Godown Cum Disaster Management Information Centers Department of Disaster Management 92-93, Mohakhali C/A, Dhaka-1212 www.ddm.gov.bd e-Tender Notice Invitation No: 51.01.0000.025.14.094.19-110 Date: 10.04.2019 e-Tender is invited in the national e-GP system Portal (http://www.eprocure.gov.bd) for the Procurement of below mentioned Package which is available in tender notice under e-GP system portal. This is an online tender where only e-Tender will be accepted in the National e-GP Portal and no offline/hard copies will be accepted. To submit e-Tender Registration in the National portal (http://www.eprocure.gov.bd) is required. The fees for downloading the e-Tender Document from the National e-GP system Portal have to be deposited online through any registered Banks branches of serial number 01-61 up to 08.05.2019 till 16:00. Detailed Description of works Package No, Tender ID & Dropping Schedule are as follows: Sl. Tender Closing& Opening Package No Name of Work No ID Date Time Construction of Dhaka District Relief Godown Cum Disaster 01 DDM/DRG/001/Dhaka-01 300146 09-May-2019 13:00 Management Information Center-1 Construction of Dhaka District Relief Godown Cum Disaster 02 DDM/DRG/002/Dhaka-02 300234 09-May-2019 13:00 Management Information Center-2 Construction of Kisorganj District Relief Godown Cum Disaster 03 DDM/DRG/004/Kishorganj 304489 09-May-2019 13:00 Management Information Center Construction of Tangail District