Moriarty Research and Reflection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16192-4 — Saigon at War Heather Stur Excerpt More Information Introduction It was a tense week in Saigon in October 1974, when a South Vietnamese university student slipped into the office of the city’s archbishop to deliver a letter addressed to North Vietnamese youth. Archbishop Nguyen Van Binh was headed to the Vatican for an international meeting of Catholic leaders, and he promised the student he would hand the letter off to his Hanoi counterpart when he saw him at the conference. The letter implored North Vietnamese students to join southern youth in demanding an end to the fighting that the 1973 Paris Peace Agreement was supposed to have halted. Both the archbishop and the student risked arrest for circulating the letter. Authorities had raided the offices and shut down the operations of four newspapers that had published it. That the leader of South Vietnam’s Catholics would be involved in clandestine communication between North and South Vietnamese students would have been surprising in the early 1960s, but by the mid-seventies, many Vietnamese Catholics had grown weary enough of the war that they saw peace and reconciliation, even if under Hanoi’s control, as the better alternative to endless violence.1 Within days of the Saigon newspapers publishing the letter, splashed across the front page of the Washington Post was an Associated Press photograph of Madame Ngo Ba Thanh, a prominent anti-government activist, leading Buddhist monks and nuns in a protest against the war 1 Telegram from Secretary of State to All East Asian and Pacific Diplomatic Posts, Oct. -

DRAFT: DO NOT CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION 1 Breaker of Armies: Air Power in the Easter Offensive and the Myth of Linebacker I

DRAFT: DO NOT CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION Breaker of Armies: Air Power in the Easter Offensive and the Myth of Linebacker I and II Phil Haun and Colin Jackson Abstract: Most traditional accounts identify the Linebacker I and Linebacker II campaigns as the most effective and consequential uses of U.S. air power in the Vietnam War. They argue that deep interdiction in North Vietnam played a central role in the defeat of the Easter Offensive and that subsequent strategic attacks on Hanoi forced the North Vietnamese to accept the Paris Accords. We find that these conclusions are false. The Linebacker campaigns were rather ineffective in either stopping the Communist offensive or compelling concessions. The most effective and consequential use of U.S. air power came in the form of close air support and battlefield air interdiction directly attacking the North Vietnamese Army in South Vietnam. The success of these air strikes hinged on the presence of a U.S.-operated, tactical air control system that incorporated small numbers of ground advisors, air liaison officers, and forward air controllers. This system, combined with abundant U.S. aircraft and a reasonably effective allied army, was the key to breaking the Easter Offensive and compelling Hanoi to agree to the Paris Accords. The effectiveness of CAS and BAI and the failure of interdiction and strategic attack in the Vietnam War have important implications for the use of air power and advisors in contemporary conflicts in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan. Most accounts of U.S. air power in the latter phases of the Vietnam War revolve around the Linebacker I and II campaigns of 1972.1 While scholars offer a range of explanations for the success of these campaigns, the U.S. -

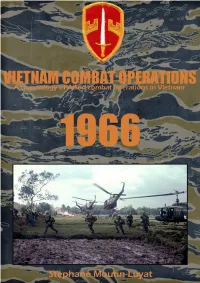

1966 Vietnam Combat Operations

VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1966 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam 1 VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1966 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam Stéphane Moutin-Luyat – 2009 distribution unlimited Front cover: Slicks of the 118th AHC inserting Skysoldiers of the 173d Abn Bde near Tan Uyen, Bien Hoa Province. Operation DEXTER, 4 May 1966. (118th AHC Thunderbirds website) 2 VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1966 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam This volume is the second in a series of chronologies of Allied headquarters: 1st Cav Div. Task organization: 1st Bde: 2-5 combat operations conducted during the Vietnam War from Cav, 1-8 Cav, 2-8 Cav, 1-9 Cav (-), 1-12 Cav, 2-19 Art, B/2-17 1965 to 1973, interspersed with significant military events and Art, A/2-20 Art, B/6-14 Art. 2d Bde: 1-5 Cav, 2-12 Cav, 1-77 augmented with a listing of US and FWF units arrival and depar- Art. Execution: The 1st Bde launched this operation north of ture for each months. It is based on a chronology prepared for Route 19 along the Cambodian border to secure the arrival of the Vietnam Combat Operations series of scenarios for The the 3d Bde, 25th Inf Div. On 4 Jan, the 2d Bde was committed to Operational Art of War III I've been working on for more than conduct spoiling attacks 50 km west of Kontum. Results: 4 three years, completed with additional information obtained in enemy killed, 4 detained, 6 US KIA, 41 US WIA. -

1967 Vietnam Combat Operations

VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1967 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam 1 VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1967 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam Stéphane Moutin-Luyat – 2011 distribution unlimited Front cover: Members of Company C, 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry, 1st Brigade, 4th Infantry Division, descend the side of Hill 742 located five miles northwest of Dak To, Operation MACARTHUR, November 1967. (Center of Military History) 2 VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1967 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam This volume is the third in a series of chronologies of Allied Cav: 1-10 Cav (-), Co 1-69 Arm, Plat 1-8 Inf, 3-6 Art (-); Div combat operations conducted during the Vietnam War from Arty: 6-14 Art, 5-16 Art (-); Div Troops: 4th Eng Bn (-). Task 1965 to 1973, interspersed with significant military events and organization (effective 8 March): 1 st Bde, 4 th Inf Div : 1-8 Inf, augmented with a listing of US and FWF units arrival and depar- 3-8 Inf, 2-35 Inf, 6-29 Art (-), C/2-9 Art, A/4th Eng. 2d Bde, 4 th ture for each months. It is based on a chronology prepared for Inf Div: 1-12 Inf, 1-22 Inf, 4-42 Art (-), B/4th Eng; TF 2-8 Inf the Vietnam Combat Operations series of scenarios for The Inf: 2-8 Inf (-), B/6-29 Art, A/4-42 Art; TF 1-69 Arm: 1-69 Arm Operational Art of War III I've been working on for more than (-), Plat 2-8 Inf, B/3-6 Art, A/5-16 Art; TF 1-10 Cav: 1-10 Cav four years, completed with additional information obtained in (-), Co 1-69 Arm, C/3-4 Cav (-), Plat 2-8 Inf, 3-6 Art (-), B/7-13 primary source documents. -

Records of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RECORDS OF THE MILITARY ASSISTANCE COMMAND VIETNAM Part 1. The War in Vietnam, 1954-1973 MACV Historical Office Documentary Collection UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RECORDS OF THE MILITARY ASSISTANCE COMMAND VIETNAM Part 1. The War in Vietnam, 1954-1973 MACV Historical Office Documentary Collection Microfilmed from the holdings of the Library of the U.S. Army Military History Institute Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania Project Editor and Guide Compiler Robert E. Lester A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam [microform] : microfilmed from the holdings of the Library of the U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania / project editor, Robert Lester. microfilm reels. Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Robert E. Lester. Contents: pt. 1. The war in Vietnam, 1954-1973, MACV Historical Office Documentary Collection -- pt. 2. Classified studies from the Combined Intelligence Center, Vietnam, 1965-1973. ISBN 1-55655-105-3 (microfilm : pt. 1) ISBN 1-55655-106-1 (microfilm : pt. 2) 1. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961-1975-Sources. 2. United States. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam-Archives. I. Lester, Robert. II. United States. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. III. U.S. Army Military History Institute. Library. [DS557.4] 959.704'3-dc20 90-12374 CIP -

Who Was Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn?”: Theorizing the Relationship Between History and Cultural Memory Evyn Lê Espiritu Pomona College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2013 “Who was Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn?”: Theorizing the Relationship between History and Cultural Memory Evyn Lê Espiritu Pomona College Recommended Citation Lê Espiritu, Evyn, "“Who was Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn?”: Theorizing the Relationship between History and Cultural Memory" (2013). Pomona Senior Theses. 92. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/92 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Who was Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn?” Theorizing the Relationship between History and Cultural Memory by Evyn Lê Espiritu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of a Bachelor’s Degree in History Pomona College April 12, 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 A Note on Terms 3 In the Beginning: Absence and Excess 4 Constructing a Narrative: Situating Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn 17 Making Space in the Present: South Vietnamese American Cultural Memory Acts 47 Remembering in Private: The Subversive Practices of Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn’s Relatives 89 The End? Writing History and Transferring Memory 113 Primary Sources 116 Secondary Sources 122 1 Acknowledgements The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the advice and support of several special individuals. In addition to all my interviewees, I would like to especially thank: my thesis readers, Prof. Tomás Summers Sandoval (History) and Prof. Jonathan M. Hall (Media Studies), for facilitating my intellectual development and encouraging interdisciplinary connections my mother, Dr. -

1965 Vietnam Combat Operations

VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1965 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam 1 VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1965 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam Stéphane Moutin-Luyat – 2009 distribution unlimited Front cover: Lt. Johnny Libs, 2d Platoon, Company C, 2d Battalion, 16th Infantry, 1st Inf Div. Bien Hoa, September 1965. (First Division Museum) 2 VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1965 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam This volume is the first in a series of chronologies of Allied 8th Fld Hosp combat operations conducted during the Vietnam War from 765th Trans Bn 1965 to 1973, interspersed with significant military events and 56th Trans Co augmented with a listing of US and FWF units arrival and depar- 330th Trans Co ture for each months. It is based on a chronology prepared for 339th Trans Co the Vietnam Combat Operations series of scenarios for The 611th Trans Co Operational Art of War III I've been working on for more than 101st ASA Co three years, completed with additional information obtained in Marine Unit Vietnam (CTU 79.3.5) primary source documents. It does not pretend to be a compre- Sub-Unit 2, MABS-16 hensive listing, data are scarcely available when dealing with HMM-365 South Vietnamese or Korean operations, for example. Co L, 3/9 Marines 2d Air Division Each operation is presented in the following format: 507th TCG 315th ACG (TC) Date Operation: name of the operation, when available 33d TG Location: population centers, landmarks, province. Type: type 34th TG of operation, when available. Controlling headquarters: when 23d ABG available. -

Out of Bounds : Transnational Sanctuary in Irregular Warfare / by Thomas A

Out of Bounds OP 17 Transnational Sanctuary in Irregular Warfare Thomas A. Bruscino, Jr. Global War on Terrorism Occasional Paper 17 Combat Studies Institute Press Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Out of Bounds OOPP 1177 Transnational Sanctuary in Irregular Warfare by Thomas A. Bruscino, Jr. Combat Studies Institute Press Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bruscino, Thomas A. Out of bounds : transnational sanctuary in irregular warfare / by Thomas A. Bruscino, Jr. p. cm. -- (Global War on Terrorism occasional paper 17) 1. Transnational sanctuaries (Military science)--Case studies. 2. Transnational sanctuaries (Mili- tary science)--History--20th century. 3. Vietnam War, 1961-1975--Campaigns. 4. Afghanistan--History--Soviet occupation, 1979-1989--Campaigns. I. Title. II. Series. U240.B78 2006 958.104’5--dc22 2006027469 CSI Press publications cover a variety of military history topics. The views expressed in this CSI Press publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense. A full list of CSI Press publications, many of them available for downloading, can be found at http://www.cgsc.army.mil/carl/resources/csi/csi.asp. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 0-16-076846-2 Foreword In this timely Occasional Paper, Dr. Tom Bruscino analyzes a critical issue in the GWOT, and one which has bedeviled counterinsurgents past and present. He examines the role played by sanctuaries as they relate to irregular warfare in two conflicts. -

Breaker of Armies Phil Haun and Colin Jackson Air Power in the Easter Offensive and the Myth of Linebacker I and II in the Vietnam War

Breaker of Armies Breaker of Armies Phil Haun and Colin Jackson Air Power in the Easter Offensive and the Myth of Linebacker I and II in the Vietnam War Theorists and practi- tioners have long debated what constitutes the most effective use of air power. Arguments have pitted advocates of deep strike (strategic attack and air inter- diction) against proponents of a combined arms, direct attack on enemy ar- mies (close air support and battleªeld air interdiction). This article examines this debate in the context of the 1972 Easter Offensive in the Vietnam War. The traditional conclusion that the air interdiction and strategic attack of the Linebacker I and II campaigns were decisive is wrong. Instead, air power was most effective in the direct attack on the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) in the south. Most accounts of U.S. air power in the latter phases of the Vietnam War re- volve around the Linebacker campaigns of 1972.1 Although scholars offer a range of explanations for the success of these campaigns, the United States Air Force (USAF) has long seen them as proof of the politically decisive effects of interdiction and strategic attack. The widely held belief that these independent air operations on North Vietnam coerced Hanoi into signing the 1973 Paris peace accords is wrong.2 It was, rather, the defeat of the NVA during the Easter Offensive in South Vietnam that convinced the North to accept a peace agree- ment in October 1972. U.S. air power was decisive, not with deep interdiction or strategic air strikes, but by stopping North Vietnam’s blitzkrieg in the south and breaking its army in the process. -

The Ambiguous Legacy of Ngô Đình Diệm in South Vietnam's

RESEARCH ESSAY SEAN FEAR The Ambiguous Legacy of Ngô Đình Diệmin South Vietnam’s Second Republic (–) n November , , Sài Gòn’s Notre Dame Basilica is packed with Ospectators, and the streets outside teem with throngs of onlookers. Vietnam Press, the Republic of Vietnam’s official news service, reports that over five thousand people turn out for the commemorations, which continue later that afternoon at the Mạc Đĩnh Chi Cemetery. In attendance are a number of political notables, including the president’s wife, Vice President TrầnVănHương, several cabinet ministers, and even former Generals Đỗ Mậu and Lê Văn Nghiêm, both noted enemies of the man being honoured. At the cemetery, standing next to the fallen man’s grave, is Trương Công Cừu, Chairman of the Revolutionary Social Humanist Party [ViệtNam Nhân Xã Cách Mạng Đảng], or Nhân Xã, widely known in political circles as a thinly veiled attempt to revive the former governing Cần Lao Party. Trương Công Cừu eulogizes the man they have all gathered to remember: “He was the incarnation of the noblest ideals of our race and mankind. Animated by a glorious ideal from childhood, he consecrated his whole existence to the righteous cause ...he brought South Vietnam from a depen- dent, exhausted, disordered and disorganized position into the ranks of a sovereign, prosperous and well-disciplined nation, respected by the whole world, friends and foes alike.” But the death of the man to whom Trương Journal of Vietnamese Studies, Vol. , Issue , pps. –. ISSN -X, electronic -. © by The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Please direct all requests for permission to photocopy or reproduce article content through the University of California Press’ Rights and Permissions website, at http://www.ucpressjournals.com/reprintinfo.asp. -

Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and 1950S Southern Vietnam

CAULDRON OF RESISTANCE A volume in the series The United States in the World Edited by Mark Philip Bradley, David C. Engerman, and Paul A. Kramer A list of titles in this series is available at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. CAULDRON OF RESISTANCE Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and 1950s Southern Vietnam Jessica M. Chapman Cornell University Press Ithaca and London Copyright © 2013 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2013 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chapman, Jessica M. (Jessica Miranda), 1977– Cauldron of resistance : Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and 1950s southern Vietnam / Jessica M. Chapman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5061-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Vietnam (Republic)—Politics and government. 2. Ngo, DInh Diem, 1901–1963. 3. Vietnam (Republic)—Foreign relations— United States. 4. United States—Foreign relations—Vietnam (Republic) I. Title. DS556.9.C454 2013 327.59707309'045—dc23 2012028850 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fi bers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. -

See It Through with Nguyen Van Thieu

See It Through with Nguyen Van Thieu SEE IT THROUGH WITH NGUYEN VAN THIEU THE NIXON ADMINISTRATION EMBRACES A DICTATOR, 1969-1974 By JOSHUA K. LOVELL, BA, MA A Dissertation Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Joshua K. Lovell, June 2013 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2013), Hamilton, Ontario (History) TITLE: See It Through with Nguyen Van Thieu: The Nixon Administration Embraces a Dictator, 1969-1974 AUTHOR: Joshua K. Lovell, BA (University of Waterloo), MA (University of Waterloo) SUPERVISOR: Professor Stephen M. Streeter NUMBER OF PAGES: ix, 304 ii ABSTRACT Antiwar activists and Congressional doves condemned the Nixon administration for supporting South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu, whom they accused of corruption, cruelty, authoritarianism, and inefficacy. To date, there has been no comprehensive analysis of Nixon’s decision to prop up a client dictator with seemingly so few virtues. Joshua Lovell’s dissertation addresses this gap in the literature, and argues that racism lay at the root of this policy. While American policymakers were generally contemptuous of the Vietnamese, they believed that Thieu partially transcended the alleged limitations of his race. The White House was relieved to find Thieu, who ushered South Vietnam into an era of comparative stability after a long cycle of coups. To US officials, Thieu appeared to be the only leader capable of planning and implementing crucial political, social, and economic policies, while opposition groups in Saigon’s National Assembly squabbled to promote their own narrow self-interests. Thieu also promoted American-inspired initiatives, such as Nixon’s controversial Vietnamization program, even though many of them weakened his government.