Inspiring Insights from an English Teaching Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

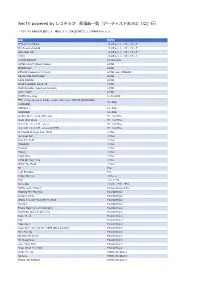

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

{Download PDF} Japanese Human Resource Management Labour-Management Relations and Supply Chain Challenges in Asia 1St Edition Pd

JAPANESE HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT LABOUR- MANAGEMENT RELATIONS AND SUPPLY CHAIN CHALLENGES IN ASIA 1ST EDITION Author: Naoki Kuriyama Number of Pages: --- Published Date: --- Publisher: --- Publication Country: --- Language: --- ISBN: 9783319430522 DOWNLOAD: JAPANESE HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT LABOUR- MANAGEMENT RELATIONS AND SUPPLY CHAIN CHALLENGES IN ASIA 1ST EDITION Japanese Human Resource Management Labour-Management Relations and Supply Chain Challenges in Asia 1st edition PDF Book "A Tail of Hope's Faith" is a love story between a dog and her family as they experience physical and emotional healing beyond their wildest imagination, which brings them full circle with life itself. Univ. A non-Thai, especially a Westerner, will appreciate the opportunity to learn some really strong and direct language that his Thai colleagues would rather he not know. Please note: this notebook is also available in small and medium sizes. Invasive Species Management in Glacier Bay National Park Preserve: 2012 Summary ReportThis book covers all aspect of legume production management technologies, plant ecological response, nutrients management, biological nitrogen fixation, molecular approaches, potential cultivars, biodiversity management under climate change. Find more at www. Next, you'll drill down to detailed techniques for applying and extending these features with C 4. Lyneis-3. CHABERT, Centre Technique des Industries M~caniques, Sen1is, France F. Its purpose was to give a brief position statement or comment, from an integrational perspective, on a variety of controversial issues, in order to provoke further discussion and to show that integrationism is not restricted to topics of interest solely to linguists. They illustrate the limitations of reform initiatives which focus on school leaders tot he exclusion of the many other organisations which affect school, such as national and local governments, professional associations and school communities. -

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org $4.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Background 03 Trails and Settlements 03 Shelters and Dwellings 04 Clothing and Dress 07 Arts and Crafts 08 Religions 09 Medicine 10 Agriculture, Hunting, and Fishing 11 The Fur Trade 12 Five Major Tribes of Ohio 13 Adapting Each Other’s Ways 16 Removal of the American Indian 18 Ohio Historical Society Indian Sites 20 Ohio Historical Marker Sites 20 Timeline 32 Glossary 36 The Ohio Historical Society 1982 Velma Avenue Columbus, OH 43211 2 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio HISTORICAL BACKGROUND In Ohio, the last of the prehistoric Indians, the Erie and the Fort Ancient people, were destroyed or driven away by the Iroquois about 1655. Some ethnologists believe the Shawnee descended from the Fort Ancient people. The Shawnees were wanderers, who lived in many places in the south. They became associated closely with the Delaware in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Able fighters, the Shawnees stubbornly resisted white pressures until the Treaty of Greene Ville in 1795. At the time of the arrival of the European explorers on the shores of the North American continent, the American Indians were living in a network of highly developed cultures. Each group lived in similar housing, wore similar clothing, ate similar food, and enjoyed similar tribal life. In the geographical northeastern part of North America, the principal American Indian tribes were: Abittibi, Abenaki, Algonquin, Beothuk, Cayuga, Chippewa, Delaware, Eastern Cree, Erie, Forest Potawatomi, Huron, Iroquois, Illinois, Kickapoo, Mohicans, Maliseet, Massachusetts, Menominee, Miami, Micmac, Mississauga, Mohawk, Montagnais, Munsee, Muskekowug, Nanticoke, Narragansett, Naskapi, Neutral, Nipissing, Ojibwa, Oneida, Onondaga, Ottawa, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Peoria, Pequot, Piankashaw, Prairie Potawatomi, Sauk-Fox, Seneca, Susquehanna, Swamp-Cree, Tuscarora, Winnebago, and Wyandot. -

Further Development of the Tail-Equivalent Linearization Method for Nonlinear Stochastic Dynamics

Further Development of the Tail-Equivalent Linearization Method for Nonlinear Stochastic Dynamics by Marco Broccardo A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering – Civil and Environmental Engineering and the Designated Emphasis in Computational Science and Engineering in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Armen Der Kiureghian, Chair Professor Sanjay Govindjee Professor David Ross Brillinger Fall 2014 Further Development of the Tail-Equivalent Linearization Method for Nonlinear Stochastic Dynamics Copyright 2014 by Marco Broccardo 1 Abstract Further Development of the Tail-Equivalent Linearization Method for Nonlinear Stochastic Dynamics by Marco Broccardo Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering – Civil and Environmental Engineering and the Designated Emphasis in Computational Science and Engineering University of California, Berkeley Professor Armen Der Kiureghian, Chair This dissertation provides the foundation for an in-depth understanding and significant de- velopment of the tail-equivalent linearization method (TELM) to solve different classes of nonlinear random vibration problems. The TELM is a linearization method that uses the first-order reliability method (FORM) to define a tail-equivalent linear system (TELS) and to estimate the tail of the response distribution for nonlinear systems under stochastic in- puts. The method was originally developed in the time domain for inelastic systems. It was later extended in the frequency domain for a specific class of nonlinear excitations, while the frequency domain version for inelastic systems is covered in the present work. This dissertation mathematically formalizes and extends TELM analysis with different types of discretization of the input process. -

Summer Edition

MESSENGER POST MEDIA PetTales SUMMER EDITION Advertising supplement for June 25, 2015 2 PET TALES • SUMMER EDITION 2015 How a pet friendly practice can make it easier How a “Cat Friendly” practice can make it easier BY EMBER COUTURE, DVM & JOANNE HACH, DVM While cats are the most popular companion Your veterinary team is at a disadvantage animal at this point, they lag far behind in assessing a cat’s health without this their canine counterparts in visits to their input. Observant families may provide key veterinarian. The goal of this article is information for this creature that is secretive to increase awareness of the benefits of by nature. seeking routine health care for kitties and The value of the second tool, the physical to explain how an American Association of exam, is drastically underestimated. Feline Practitioners (AAFP) certified “Feline Families are surprised at the amount of Friendly Practice” has worked to make this information our hands and eyes gather as sometimes stressful process easier. they roam from the nose to the tip of the Your veterinary healthcare team is dedicated tail. Every body system is assessed and the to preserving the health of your cat. information recorded in the patient’s record Examinations once or twice a year give us for future reference. the opportunity to gain familiarity with each Eyes: Is there conjunctivitis, pigment cat and to counsel their families on changing changes in any part of the eyes or retinal preventative recommendations. changes? Do both eyes look the same? Do Examinations also give us the chance to find they respond appropriately to stimuli like problems early when intervention may be light? less invasive. -

Edible Insects

1.04cm spine for 208pg on 90g eco paper ISSN 0258-6150 FAO 171 FORESTRY 171 PAPER FAO FORESTRY PAPER 171 Edible insects Edible insects Future prospects for food and feed security Future prospects for food and feed security Edible insects have always been a part of human diets, but in some societies there remains a degree of disdain Edible insects: future prospects for food and feed security and disgust for their consumption. Although the majority of consumed insects are gathered in forest habitats, mass-rearing systems are being developed in many countries. Insects offer a significant opportunity to merge traditional knowledge and modern science to improve human food security worldwide. This publication describes the contribution of insects to food security and examines future prospects for raising insects at a commercial scale to improve food and feed production, diversify diets, and support livelihoods in both developing and developed countries. It shows the many traditional and potential new uses of insects for direct human consumption and the opportunities for and constraints to farming them for food and feed. It examines the body of research on issues such as insect nutrition and food safety, the use of insects as animal feed, and the processing and preservation of insects and their products. It highlights the need to develop a regulatory framework to govern the use of insects for food security. And it presents case studies and examples from around the world. Edible insects are a promising alternative to the conventional production of meat, either for direct human consumption or for indirect use as feedstock. -

August Derleth Young Writers' Anthology

August Derleth Young Writers’ Anthology 2013 Third & Fourth Grade Who was August Derleth? August Derleth was Wisconsin’s most prolific writer, producing over 150 books in his lifetime. He wrote poetry, short stories, journals, historical and romantic novels, mysteries and books for children. He was also an editor, publisher, and the owner of Arkham House, a publishing house devoted exclusively to the publication of ghost stories, fantasy, science fiction and the macabre. August Derleth was a man of simple needs. He was very generous in sharing his talents and interests with students and aspiring writers. Derleth was a born naturalist and a realistic critic. His complex nature made him the subject of controversy, but those who knew him well defend his nonconformity. They point out his fondness for another nonconformist, Henry Thoreau, and would liken them, forgetting that Thoreau was a much more reclusive man. August Derleth loved his small town, Sauk Prairie, and the people who lived there. He loved his people, not in spite of their human qualities, but because of them. Many of his writings tell about life in Sauk Prairie and he saw and experienced it. This may well be the measure of his writing stature. ANNE HORJUS ILLUSTRATOR The multitalented, Dutch artist Anne Horjus was raised in a small village near the Wadden Sea in the Northern part of the Netherlands known as Friesland. From kindergarten on he (yes, Anne, pronounced Ann-uh, is an old fashioned Friesian boys name) had to bike to school. Everyday he traveled through farm fields and other tiny villages, passing many Friesian farms and countless migrating birds using the coastline as their route. -

Versão Revisada 2017

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS MODERNAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ESTUDOS LINGUÍSTICOS E LITERÁRIOS EM INGLÊS LEINA CLÁUDIA VIANA JUCÁ DAS HISTÓRIAS QUE NOS HABITAM: POR UMA FORMAÇÃO DE PROFESSORES DE INGLÊS PARA O BRASIL Versão Revisada SÃO PAULO 2017 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS MODERNAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ESTUDOS LINGUÍSTICOS E LITERÁRIOS EM INGLÊS DAS HISTÓRIAS QUE NOS HABITAM: POR UMA FORMAÇÃO DE PROFESSORES DE INGLÊS PARA O BRASIL Leina Cláudia Viana Jucá Tese de doutorado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos Linguísticos e Literários em Inglês do Departamento de Letras Modernas da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, para a obtenção do título de Doutora em Letras. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Walkyria Monte Mór Versão Revisada SÃO PAULO 2017 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Catalogação na Publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo JUCÁ, Leina Cláudia Viana J91h Das Histórias Que Nos Habitam: por uma formação de professores de inglês para o Brasil / Leina Cláudia Viana JUCÁ ; orientador Walkyria Maria MONTE MÓR. - São Paulo, 2017. 268 f. Tese (Doutorado)- Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de Letras Modernas. Área de concentração: Estudos Linguísticos e Literários em Inglês. 1. Formação de professores de línguas. -

Transcript of Proceedings

In the Matter of: Tribal Consultation Hearing Reporter's Transcript of Proceedings 07/25/2013 Job #: 22396 (818)988-1900 1 TRIBAL CONSULTATION 2 DRAFT REVISIONS TO FEDERAL ACKNOWLEDGMENT REGULATIONS 3 (25 CFR 83) 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 REPORTER'S TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS 11 THURSDAY, JULY 25, 2013 12 9:11 A.M. 13 14 15 HOTEL CORQUE 16 400 ALISAL ROAD 17 SOLVANG, CALIFORNIA 93463 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 FILE NO: 22396 25 REPORTED BY: WENDY DRISCOLL, C.S.R. NO. 12480 Personal Court Reporters, Inc. Page: 1 1 APPEARANCES: 2 3 FOR THE OFFICE OF REGULATORY AFFAIRS & COLLABORATIVE ACTION: 4 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 5 BY: ELIZABETH APPEL 1849 C STREET, NW 6 MS 4141 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20240 7 8 FOR THE OFFICE OF THE SOLICITOR: 9 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 10 BY: KAITLYN CHINN 1849 C STREET, NW 11 MS 4141 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20240 12 13 FOR THE INDIAN AFFAIRS: 14 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIORS 15 BY: LAWRENCE S. ROBERTS, DEPUTY ASSISTANT SECRETARY 16 1849 C. STREET, NW MS4159-MIB 17 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20240 202.208.7163 18 [email protected] 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Personal Court Reporters, Inc. Page: 2 1 I N D E X 2 SPEAKERS: PAGE 3 MIKE RODRIGUEZ 20 4 KEN WOODROW 23, 28, 33, 177 5 MICHAEL LOMBARD 23 6 FLORENCE DICK 25 7 LISA ALBRITRE 27, 50, 159 8 BEN WOLF 32, 84 9 DAVID GALVAN 29, 91 10 TONY CERDA 35, 102 11 ROSE MARY 40 12 ELIZABETH SHOULDERMAN(PHONETIC)41, 108 13 LYDIA PONCE 43, 110, 191 14 HEIDI HARPER PEREZ 46 15 GINA LAMB (PHONETIC) 53, 76 16 SANDRA CHAPMAN 55, 109, 188 17 JOHN AMMON 61 18 MANDY MARINE 67 19 SHANE CHAPPAROSA 77 20 JULIE DICK TEX 78 21 ANDREW LARA 83, 104, 175 22 JESSICA BEVINS (PHONETIC) 88 23 SANDY HESTER 93 24 JEROME FREDERICKS 97 25 // Personal Court Reporters, Inc. -

Appendix B: Text Exemplars and Sample Performance Tasks

common core state STANDARDs FOR english Language arts & Literacy in History/social studies, science, and technical subjects appendix B: text exemplars and sample Performance tasks Common Core State StandardS for engliSh language artS & literaCy in hiStory/SoCial StudieS, SCienCe, and teChniCal SubjeCtS exemplars of reading text complexity, Quality, and range & sample Performance tasks related to core standards Selecting Text Exemplars The following text samples primarily serve to exemplify the level of complexity and quality that the Standards require all students in a given grade band to engage with. Additionally, they are suggestive of the breadth of texts that stu- dents should encounter in the text types required by the Standards. The choices should serve as useful guideposts in helping educators select texts of similar complexity, quality, and range for their own classrooms. They expressly do not represent a partial or complete reading list. The process of text selection was guided by the following criteria: • Complexity. Appendix A describes in detail a three-part model of measuring text complexity based on quali- tative and quantitative indices of inherent text difficulty balanced with educators’ professional judgment in matching readers and texts in light of particular tasks. In selecting texts to serve as exemplars, the work group began by soliciting contributions from teachers, educational leaders, and researchers who have experience working with students in the grades for which the texts have been selected. These contributors were asked to recommend texts that they or their colleagues have used successfully with students in a given grade band. The work group made final selections based in part on whether qualitative and quantitative measures indicated that the recommended texts were of sufficient complexity for the grade band. -

BIKOL DICTIONARY PALI LANGUAGE TEXTS: PHILIPPINES (Pacific and Asian Linguistics Institute) Howard P

BIKOL DICTIONARY PALI LANGUAGE TEXTS: PHILIPPINES (Pacific and Asian Linguistics Institute) Howard P. McKaughan Editor ii BIKOL DICTIONARY by Malcolm W. Mintz Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Inter- national (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. The license also permits readers to create and share de- rivatives of the work, so long as such derivatives are shared under the same terms of this license. Commercial uses require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824878917 (PDF) 9780824878924 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. The work reported herein was performed pursuant to a contract with the Peace Corps, Washington, D. C. 20525. The opinions ex- pressed herein are those of the author and should not be con- strued as representing the opinions or policies of any agency of the United States government. Copyright © 1971 by University of Hawaii Press All rights reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My partner in collecting the information that appears in this dictionary was Jose Britanico and to him goes my sincerest thanks.