Economic Forecasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

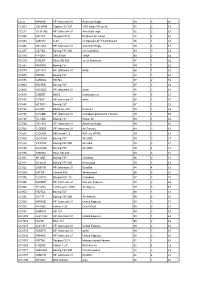

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Aviation in the Pacific International Aviation Services Are Crucial to Trade, Growth, and Development in the Pacific Region

Pacific Studies Series About Oceanic Voyages: Aviation in the Pacific International aviation services are crucial to trade, growth, and development in the Pacific region. Improved access provided by international aviation from every other region in the world to an increasing number of islands is opening new opportunities. Tourism contributes substantially to income and employment in many Pacific countries, usually in areas outside of the main urban centers, and enables air freight services for valuable but perishable commodities that would otherwise not be marketable. Although some features of the Pacific region make provision of international aviation services a challenge, there have also been some notable successes that offer key lessons for future development. Case studies of national aviation sector experience show the value of operating on commercial principles, attracting international and OCEANIC V private-sector capital investment, assigning risk where it can best be managed, and liberalizing market access. Integration of the regional market for transport services, combined with harmonized but less restrictive regulations, would facilitate a greater range of services at more competitive prices. Pacific island country governments have the ability to create effective operating environments. When they do so, experience O shows that operators will respond with efficient service provision. YAGES: About the Asian Development Bank Av ADB aims to improve the welfare of the people in the Asia and Pacific region, IATI particularly the nearly 1.9 billion who live on less than $2 a day. Despite many success stories, the region remains home to two thirds of the world’s poor. ADB is O N IN THE PACIFIC a multilateral development finance institution owned by 67 members, 48 from the region and 19 from other parts of the globe. -

July/August 2000 Volume 26, No

Irfc/I0 vfa£ /1 \ 4* Limited Edition Collectables/Role Model Calendars at home or in the office - these photo montages make a statement about who we are and what we can be... 2000 1999 Cmdr. Patricia L. Beckman Willa Brown Marcia Buckingham Jerrie Cobb Lt. Col. Eileen M. Collins Amelia Earhart Wally Funk julie Mikula Maj. lacquelyn S. Parker Harriet Quimby Bobbi Trout Captain Emily Howell Warner Lt. Col. Betty Jane Williams, Ret. 2000 Barbara McConnell Barrett Colonel Eileen M. Collins Jacqueline "lackie" Cochran Vicky Doering Anne Morrow Lindbergh Elizabeth Matarese Col. Sally D. Woolfolk Murphy Terry London Rinehart Jacqueline L. “lacque" Smith Patty Wagstaff Florene Miller Watson Fay Cillis Wells While They Last! Ship to: QUANTITY Name _ Women in Aviation 1999 ($12.50 each) ___________ Address Women in Aviation 2000 $12.50 each) ___________ Tax (CA Residents add 8.25%) ___________ Shipping/Handling ($4 each) ___________ City ________________________________________________ T O TA L ___________ S ta te ___________________________________________ Zip Make Checks Payable to: Aviation Archives Phone _______________________________Email_______ 2464 El Camino Real, #99, Santa Clara, CA 95051 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS (ISSN 0273-608X) 99 NEWS INTERNATIONAL Published by THE NINETV-NINES* INC. International Organization of Women Pilots A Delaware Nonprofit Corporation Organized November 2, 1929 WOMEN PILOTS INTERNATIONAL HEADQUARTERS Box 965, 7100 Terminal Drive OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OFTHE NINETY-NINES® INC. Oklahoma City, -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Americaan Samoa Air Service Marketing Study-Phase Two Report

American Samoa Air Transport Marketing Study Phase Two Report August 5, 2014 i American Samoa Air Transport Marketing Study Phase Two Report, August 5, 2014 Contents Recommendations ............................................................................................. i Executive Summary ......................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... 8 Background for Recommendations .................................................................. 8 Task 5 and Task 6: Approaches to Expanding Air Services and Recommended Strategies to Provide Air Transport Services Capacity Needs ................... 19 1. Honolulu and the Mainland ...................................................................................... 20 2. Hawaiian Airlines and Competitors in the US Airline Industry ............................... 22 3. Apia, Manu'a and Savai’i.......................................................................................... 40 4. Neighboring Pacific Islands beyond Samoa ............................................................. 45 5. New Zealand and Australia ...................................................................................... 49 6. Changes in Federal Laws or Regulations ................................................................. 51 7. American Samoa Airports ........................................................................................ 56 8. Immigration -

Fields Listed in Part I. Group (8)

Chile Group (1) All fields listed in part I. Group (2) 28. Recognized Medical Specializations (including, but not limited to: Anesthesiology, AUdiology, Cardiography, Cardiology, Dermatology, Embryology, Epidemiology, Forensic Medicine, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Immunology, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oncology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Pediatrics, Pharmacology and Pharmaceutics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiology, Plastic Surgery, Preventive Medicine, Proctology, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, Speech Pathology, Sports Medicine, Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Toxicology, Urology and Virology) 2C. Veterinary Medicine 2D. Emergency Medicine 2E. Nuclear Medicine 2F. Geriatrics 2G. Nursing (including, but not limited to registered nurses, practical nurses, physician's receptionists and medical records clerks) 21. Dentistry 2M. Medical Cybernetics 2N. All Therapies, Prosthetics and Healing (except Medicine, Osteopathy or Osteopathic Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Chiropractic and Optometry) 20. Medical Statistics and Documentation 2P. Cancer Research 20. Medical Photography 2R. Environmental Health Group (3) All fields listed in part I. Group (4) All fields listed in part I. Group (5) All fields listed in part I. Group (6) 6A. Sociology (except Economics and including Criminology) 68. Psychology (including, but not limited to Child Psychology, Psychometrics and Psychobiology) 6C. History (including Art History) 60. Philosophy (including Humanities) -

Airlines Prefix Codes 1

AMERICAN AIRLINES,INC (AMERICAN EAGLE) UNITED STATES 001 0028 AA AAL CONTINENTAL AIRLINES (CONTINENTAL EXPRESS) UNITED STATES 005 0115 CO COA DELTA AIRLINES (DELTA CONNECTION) UNITED STATES 006 0128 DL DAL NORTHWEST AIRLINES, INC. (NORTHWEST AIRLINK) UNITED STATES 012 0266 NW NWA AIR CANADA CANADA 014 5100 AC ACA TRANS WORLD AIRLINES INC. (TRANS WORLD EXPRESS) UNITED STATES 015 0400 TW TWA UNITED AIR LINES,INC (UNITED EXPRESS) UNITED STATES 016 0428 UA UAL CANADIAN AIRLINES INTERNATIONAL LTD. CANADA 018 2405 CP CDN LUFTHANSA CARGO AG GERMANY 020 7063 LH GEC FEDERAL EXPRESS (FEDEX) UNITED STATES 023 0151 FX FDX ALASKA AIRLINES, INC. UNITED STATES 027 0058 AS ASA MILLON AIR UNITED STATES 034 0555 OX OXO US AIRWAYS INC. UNITED STATES 037 5532 US USA VARIG S.A. BRAZIL 042 4758 RG VRG HONG KONG DRAGON AIRLINES LIMITED HONG KONG 043 7073 KA HDA AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS ARGENTINA 044 1058 AR ARG LAN-LINEA AEREA NACIONAL-CHILE S.A. CHILE 045 3708 LA LAN TAP AIR PORTUGAL PORTUGAL 047 5324 TP TAP CYPRUS AIRWAYS, LTD. CYPRUS 048 5381 CY CYP OLYMPIC AIRWAYS GREECE 050 4274 OA OAL LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO S.A. BOLIVIA 051 4054 LB LLB AER LINGUS LIMITED P.L.C. IRELAND 053 1254 EI EIN ALITALIA LINEE AEREE ITALIANE ITALY 055 1854 AZ AZA CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES LTD. CO. CYPRUS 056 5999 YVK AIR FRANCE FRANCE 057 2607 AF AFR INDIAN AIRLINES INDIA 058 7009 IC IAC AIR SEYCHELLES UNITED KINGDOM 061 7059 HM SEY AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL NEW CALEDONIA 063 4465 SB ACI CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES CZECHOSLAVAKIA 064 2432 OK CSA SAUDI ARABIAN AIRLINES SAUDI ARABIA 065 4650 SV SVA AIR MOOREA FRENCH POLYNESIA 067 4832 QE TAH LAM-LINHAS AEREAS DE MOCAMBIQUE MOZAMBIQUE 068 7119 TM LAM SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES SYRIA 070 7127 RB SYR ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES ENTERPRISE ETHIOPIA 071 3224 ET ETH GULF AIR COMPANY G.S.C. -

The Regional Airline Industry

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1985 The regional airline industry Stephen L. Smestad The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smestad, Stephen L., "The regional airline industry" (1985). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 7986. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/7986 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s is t s , Any further r e p r in t in g of it s contents must be approved BY THE author , Ma n sfield Library Un iv e r s it y of Hout Date ; _______ 1 ^ Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE REGIONAL AIRLINE INDUSTRY BY STEPHEN L. SMESTAD B.S., PACIFIC LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY, 1975 PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1985 APPROVE fi,iBqarjybf Examiners Deân, Graduate Scïïôol , 1 Date; Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UM! Number: EP38787 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

American Samoa Air Transport Marketing Study Phase One Report, January 28, 2013

American Samoa Air Transport Marketing Study Phase One Report, January 28, 2013 American Samoa Air Transport Marketing Study Phase One Report January 28, 2013 I American Samoa Air Transport Marketing Study Phase One Report, January 28, 2013 Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................... 1 Task 1: Assess Pertinent Historical Conditions in American Samoa .............. 4 1. GDP and Population Growth ...................................................................................... 4 2. Population Growth and Net Migration ....................................................................... 4 3. Air Passenger Traffic Trends ...................................................................................... 6 4. Passenger Traffic History ........................................................................................... 6 5. Air Cargo Traffic Trends .......................................................................................... 10 Task 2: Assess the Changing Role of Transportation in the Global Economy and its Effects on American Samoa's Economy ......................................... 12 1. The Fall of Tariffs and Other Obstacles to International Trade ............................... 12 2. Aviation Deregulation and Open Skies .................................................................... 13 3. The Rise of International Trade – 1967 to Today .................................................... 17 4. The Shift of Manufacturing to Populous, -

TRAMS Master Vendor ID List 2/27/2007 Air Interface ID Travel

2/27/2007 TRAMS Master Vendor ID List Air Name Airline No. Travel Category Vendor Id Profile No. Interface ID Abx Air 832 Air 2001 5 GB Action Airlines 410 Air 2002 6 XQ Ada Air 121 Air 2003 7 ZY Adria Airways 165 Air 2004 8 JP Aer Arann Teo 684 Air 2005 9 RE Aer Lingus P.l.c. 53 Air 2006 10 EI Aero Asia International (private) Ltd. 532 Air 2007 11 E4 Aero California 78 Air 2008 12 JR Aero Costa Rica Acori S.a. 802 Air 2009 13 ML Aero Lloyd Flugreisen Gmbh And Co. Luftv 633 Air 2010 14 YP Aerocaribe 723 Air 2011 15 QA Aerochago Airlines S.a. 198 Air 2012 16 G3 Aeroejecutivo S.a. De C.v. 456 Air 2013 17 SX Aeroflot-russian International Airlines 555 Air 2014 18 SU Aerolineas Argentinas 44 Air 2015 19 AR Aerolineas Centrales De Colombia (aces) 137 Air 2016 20 VX Aerolineas Dominicanas S.a. (dominair) 725 Air 2017 21 YU Aerolineas Internacionales S.a. De C.v. 440 Air 2018 22 N2 Aeromar C. Por. A. 926 Air 2019 23 BQ Aeromexico-aerovias De Mexico S.a. De C. 139 Air 2020 24 AM Aeromonterrey S.a. De C.v. 722 Air 2021 25 7M Aeroperlas 828 Air 2022 26 WL Aeroperu - Empresa De Transportes Aereos 210 Air 2023 27 PL Aeroservicios Ecuatorianos C.a. 746 Air 2024 28 2A Aerotransportes Mas De Carga S.a. De C. 865 Air 2025 29 MY Aerovias Colombianas Ltd. (arca) 158 Air 2026 30 ZU Aerovias Venezolanas S.a. -

Aviation History in Brownwood, Texas

Aviation History in Brownwood, Texas By Frank T. Hilton December 17, 1903 The first controlled, power and sustained heavier-than-air human flight by Orville and Wilbur Wright at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. October 4, 1913 Post office Department at Washington, D. C. established areoplane mail service between Brownwood and Comanche, Texas. Lester Miller flew one trip each day, October 10, 11, 12, 1913, during the Free Fall Fair. October 7, 1914 Miss Katherine Stinson, the youngest aviator in the world made daily flights at Brownwood Free Fair. She took passengers up for $25.00 per person. March 3, 1920 Lieutenants R. W. Lutz and F. E. Monor of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, flew a new Curtis plane over Brownwood, using the landing field west of the end of Austin Avenue as their base. “Airplanes flew over Brownwood and there was a local airport near Willis Creek near 12th and 13th streets,” John A. Thomason said. He described it as a north-south runway that looked like two straight dirt paths that accommodated the wheels for take-offs and landings.” November 10, 1929 The Brown County Fair Association decided to permit airplanes coming to Brownwood to use the fifty acres inside the mile race track. This has been used successfully in the past by airplanes. 1935 Airport in Brownwood was launched as a 200 acre tract leased by the city from the county. Dr. Edgar Fuller, Dallas scientist and inventor, constructed the beacon field for the airport. WPA funds applying six-inch calicle base on runways, clearing and leveling. September 11, 1940 The Army Air Corps officially approve the 200 acre Brownwood municipal airport as headquarters for the air squadron of the Thirty-Sixth Division.