<I>Thyanta Pallidovirens</I> (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pentatomidae, Or Stink Bugs, of Kansas with a Key to Species (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) Richard J

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository Biology Faculty Papers Biology 2012 The eP ntatomidae, or Stink Bugs, of Kansas with a key to species (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) Richard J. Packauskas Fort Hays State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.fhsu.edu/biology_facpubs Part of the Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Packauskas, Richard J., "The eP ntatomidae, or Stink Bugs, of Kansas with a key to species (Hemiptera: Heteroptera)" (2012). Biology Faculty Papers. 2. http://scholars.fhsu.edu/biology_facpubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biology at FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of FHSU Scholars Repository. 210 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST Vol. 45, Nos. 3 - 4 The Pentatomidae, or Stink Bugs, of Kansas with a key to species (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) Richard J. Packauskas1 Abstract Forty eight species of Pentatomidae are listed as occurring in the state of Kansas, nine of these are new state records. A key to all species known from the state of Kansas is given, along with some notes on new state records. ____________________ The family Pentatomidae, comprised of mainly phytophagous and a few predaceous species, is one of the largest families of Heteroptera. Some of the phytophagous species have a wide host range and this ability may make them the most economically important family among the Heteroptera (Panizzi et al. 2000). As a group, they have been found feeding on cotton, nuts, fruits, veg- etables, legumes, and grain crops (McPherson 1982, McPherson and McPherson 2000, Panizzi et al 2000). -

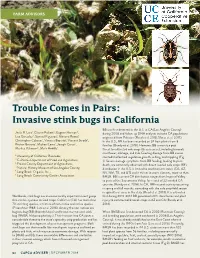

Invasive Stink Bugs in California

FARM ADVISORS Trouble Comes in Pairs: Invasive stink bugs in California BB was first detected in the U.S. in CA (Los Angeles County) 1 2 3 Jesús R. Lara , Charlie Pickett , Eugene Hannon , during 2008 and follow-up DNA analyses indicate CA populations 4 1 1 Lisa Gonzalez , Samuel Figueroa , Mariana Romo , originated from Pakistan (Reed et al. 2013; Sforza et al. 2017). 1 1 1 Christopher Cabanas , Vanessa Bazurto , Vincent Strode , In the U.S., BB has been recorded on 32 host plants from 8 1 1 5 Kristen Briseno , Michael Lewis , Joseph Corso , families (Bundy et al. 2018). However, BB is mainly a pest 6 1 Merilee Atkinson , Mark Hoddle threat to cultivated cole crops (Brassicaceae), including broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, and kale. Feeding damage from BB causes 1 University of California, Riverside; stunted/malformed vegetative growth, wilting, and stippling (Fig 2 California Department of Food and Agriculture; 1). Severe damage symptoms from BB feeding, leading to plant 3 Fresno County Department of Agriculture; death, are commonly observed with direct-seeded cole crops. BB’s 4 Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County; distribution in the U.S. is limited to southwestern states (CA, AZ, 5 Long Beach Organic, Inc.; NV, NM, TX, and UT) and it thrives in warm climates, more so than 6 Long Beach Community Garden Association BMSB. BB’s current CA distribution ranges from Imperial Valley to parts of the Sacramento Valley, for a total of 22 invaded CA counties (Bundy et al. 2018). In CA, BB has peak activity occurring in spring and fall months, coinciding with the cole crop field season in agricultural areas in the state (Reed et al. -

Tachinid Fly Parasitism and Phenology of The

Neotrop Entomol (2020) 49:98–107 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13744-019-00706-4 BIOLOGICAL CONTROL Tachinid Fly Parasitism and Phenology of the Neotropical Red-Shouldered Stink Bug, Thyanta perditor (F.) (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae), on the Wild Host Plant, Bidens pilosa L. (Asteraceae) 1 1 2 TLUCINI ,ARPANIZZI ,RVPDIOS 1Lab of Entomology, EMBRAPA Trigo, Passo Fundo, RS, Brasil 2Depto de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Univ de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil Keywords Abstract Parasites, Tachinidae flies, stink bug, Field and laboratory studies were conducted with the Neotropical red- associated plants shouldered stink bug Thyanta perditor (F.) (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) Correspondence aiming to evaluate parasitism incidence on adults by tachinid flies (Diptera: T Lucini, Lab of Entomology, EMBRAPA Tachinidae), which were raised in the laboratory for identification. Egg Trigo, Caixa Postal 3081, Passo Fundo, RS99050-970, Brasil; tiago_lucini@ deposition by flies on adult body surface was mapped. In addition, nymph hotmail.com and adult incidence on the wild host plant black jack, Bidens pilosa L. (Asteraceae), during the vegetative and the reproductive periods of plant Edited by Christian S Torres – UFRPE development was studied. Seven species of tachinid flies were obtained: Received 28 January 2019 and accepted 5 Euthera barbiellini Bezzi (73% of the total) and Trichopoda cf. pictipennis July 2019 Bigot (16.7%) were the most abundant; the remaining five species, Published online: 25 July 2019 Gymnoclytia sp.; Phasia sp.; Strongygaster sp.; Cylindromyia cf. dorsalis * Sociedade Entomológica do Brasil 2019 (Wiedemann); and Ectophasiopsis ypiranga Dios & Nihei added 10.3% of the total. Tachinid flies parasitism on T. perditor adults was significantly greater on the dorsal compared to the ventral body surface. -

Identification, Biology, Impacts, and Management of Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) of Soybean and Corn in the Midwestern United States

Journal of Integrated Pest Management (2017) 8(1):11; 1–14 doi: 10.1093/jipm/pmx004 Profile Identification, Biology, Impacts, and Management of Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) of Soybean and Corn in the Midwestern United States Robert L. Koch,1,2 Daniela T. Pezzini,1 Andrew P. Michel,3 and Thomas E. Hunt4 1 Department of Entomology, University of Minnesota, 1980 Folwell Ave., Saint Paul, MN 55108 ([email protected]; Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article-abstract/8/1/11/3745633 by guest on 08 January 2019 [email protected]), 2Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected], 3Department of Entomology, Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, The Ohio State University, 210 Thorne, 1680 Madison Ave. Wooster, OH 44691 ([email protected]), and 4Department of Entomology, University of Nebraska, Haskell Agricultural Laboratory, 57905 866 Rd., Concord, NE 68728 ([email protected]) Subject Editor: Jeffrey Davis Received 12 December 2016; Editorial decision 22 March 2017 Abstract Stink bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) are an emerging threat to soybean and corn production in the midwestern United States. An invasive species, the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Sta˚ l), is spreading through the region. However, little is known about the complex of stink bug species associ- ated with corn and soybean in the midwestern United States. In this region, particularly in the more northern states, stink bugs have historically caused only infrequent impacts to these crops. To prepare growers and agri- cultural professionals to contend with this new threat, we provide a review of stink bugs associated with soybean and corn in the midwestern United States. -

Chemical Ecology Studies in Soybean Crop in Brazil and Their Application to Pest Management

4 Chemical Ecology Studies in Soybean Crop in Brazil and Their Application to Pest Management Miguel Borges, Maria Carolina Blassioli Moraes, Raul Alberto Laumann, Martin Pareja, Cleonor Cavalcante Silva, Mirian Fernandes Furtado Michereff and Débora Pires Paula Embrapa Genetic Resources and Biotechnology. 70770-917, Brasília, DF; Brazil 1. Introduction Considering the current state of soybean production and markets around the world, it is readily apparent that it is possible to divide the countries in the world in two halves: producer and consumers’. Consumers’ countries are mainly those belonging to the European Union that have their need for proteins used for animal feeding supplied in their majority by soybean seed or meal imports (Dros, 2004). The majority of soybean production is shared (80%) between four countries: the United States, Brazil, Argentina and China (Dros, 2004). Therefore, if we consider only those countries that may supply their internal needs and exporting either seeds, meals or oils, only the USA, Brazil and Argentina remain as exporting countries (Daydé et al., 2009). In this context, Brazil is currently the world second largest soybean producer (18%) and exporter (19%), with a cultivated area for soybean around 23 million ha and production around 3 ton/ha, reaching yearly a total production of approximately 68 million ton (CONAB, 2010). Worldwide, scientists in different countries are trying to increase both the productivity and profitability of the agricultural sector of their economies, to feed growing populations and to increase the quality of life for millions of people. In recent years there has been a growing concern about environmental changes, and about how we are using the resources available in natural habitats. -

Great Lakes Entomologist the Grea T Lakes E N Omo L O G Is T Published by the Michigan Entomological Society Vol

The Great Lakes Entomologist THE GREA Published by the Michigan Entomological Society Vol. 45, Nos. 3 & 4 Fall/Winter 2012 Volume 45 Nos. 3 & 4 ISSN 0090-0222 T LAKES Table of Contents THE Scholar, Teacher, and Mentor: A Tribute to Dr. J. E. McPherson ..............................................i E N GREAT LAKES Dr. J. E. McPherson, Educator and Researcher Extraordinaire: Biographical Sketch and T List of Publications OMO Thomas J. Henry ..................................................................................................111 J.E. McPherson – A Career of Exemplary Service and Contributions to the Entomological ENTOMOLOGIST Society of America L O George G. Kennedy .............................................................................................124 G Mcphersonarcys, a New Genus for Pentatoma aequalis Say (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) IS Donald B. Thomas ................................................................................................127 T The Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) of Missouri Robert W. Sites, Kristin B. Simpson, and Diane L. Wood ............................................134 Tymbal Morphology and Co-occurrence of Spartina Sap-feeding Insects (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha) Stephen W. Wilson ...............................................................................................164 Pentatomoidea (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae, Scutelleridae) Associated with the Dioecious Shrub Florida Rosemary, Ceratiola ericoides (Ericaceae) A. G. Wheeler, Jr. .................................................................................................183 -

Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring Within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘I: Synthesis Report

Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘i: Synthesis Report Prepared by Francis G. Howarth, David J. Preston, and Richard Pyle Honolulu, Hawaii January 2012 Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘i: Synthesis Report Francis G. Howarth, David J. Preston, and Richard Pyle Hawaii Biological Survey Bishop Museum Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817 USA Prepared for EKNA Services Inc. 615 Pi‘ikoi Street, Suite 300 Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96814 and State of Hawaii, Department of Transportation, Airports Division Bishop Museum Technical Report 58 Honolulu, Hawaii January 2012 Bishop Museum Press 1525 Bernice Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i Copyright 2012 Bishop Museum All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America ISSN 1085-455X Contribution No. 2012 001 to the Hawaii Biological Survey COVER Adult male Hawaiian long-horned wood-borer, Plagithmysus kahului, on its host plant Chenopodium oahuense. This species is endemic to lowland Maui and was discovered during the arthropod surveys. Photograph by Forest and Kim Starr, Makawao, Maui. Used with permission. Hawaii Biological Report on Monitoring Arthropods within Kahului Airport Environs, Synthesis TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents …………….......................................................……………...........……………..…..….i. Executive Summary …….....................................................…………………...........……………..…..….1 Introduction ..................................................................………………………...........……………..…..….4 -

Citation: Badenes-Pérez, F. R. 2019. Trap Crops and Insectary Plants in the Order 2 Brassicales

1 Citation: Badenes-Pérez, F. R. 2019. Trap Crops and Insectary Plants in the Order 2 Brassicales. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 112: 318-329. 3 https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/say043 4 5 6 Trap Crops and Insectary Plants in the Order Brassicales 7 Francisco Rubén Badenes-Perez 8 Instituto de Ciencias Agrarias, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 28006 9 Madrid, Spain 10 E-mail: [email protected] 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 ABSTRACT This paper reviews the most important cases of trap crops and insectary 26 plants in the order Brassicales. Most trap crops in the order Brassicales target insects that 27 are specialist in plants belonging to this order, such as the diamondback moth, Plutella 28 xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae), the pollen beetle, Meligethes aeneus Fabricius 29 (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae), and flea beetles inthe genera Phyllotreta Psylliodes 30 (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). In most cases, the mode of action of these trap crops is the 31 preferential attraction of the insect pest for the trap crop located next to the main crop. 32 With one exception, these trap crops in the order Brassicales have been used with 33 brassicaceous crops. Insectary plants in the order Brassicales attract a wide variety of 34 natural enemies, but most studies focus on their effect on aphidofagous hoverflies and 35 parasitoids. The parasitoids benefiting from insectary plants in the order Brassicales 36 target insects pests ranging from specialists, such as P. xylostella, to highly polyfagous, 37 such as the stink bugs Euschistus conspersus Uhler and Thyanta pallidovirens Stål 38 (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). -

Vibratory Communication and Its Relevance to Reproductive Isolation in Two Sympatric Stink Bug Species (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae: Pentatominae)

J Insect Behav (2016) 29:643–665 DOI 10.1007/s10905-016-9585-x Vibratory Communication and its Relevance to Reproductive Isolation in two Sympatric Stink Bug Species (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae: Pentatominae) Raul A. Laumann1 & Andrej Čokl2 & Maria Carolina Blassioli-Moraes1 & Miguel Borges1 Revised: 5 October 2016 /Accepted: 18 October 2016 / Published online: 29 October 2016 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016 Abstract Communication is in phytophagous stink bugs of the subfamily Pentatominae related to mating behavior that among others includes location and recognition of the partner during calling and courting. Differences in temporal and frequency parameters of vibratory signals contributes to species reproductive isolation. Chinavia impicticornis and C. ubica are two green Neotropical stink bugs that live and mate on the same host plants. We tested the hypothesis that differences in temporal and spectral characteristics of both species vibratory signals enable their recognition to that extent that it interrupts further interspecific communication and copulation. To confirm or reject this hypothesis we monitored both species mating behaviour and recorded their vibratory songs on the non-resonant loudspeaker membranes and on the plant. The level of interspecific vibratory communication was tested also by playback experi- ments. Reproductive behavior and vibratory communication show similar patterns in both Chinavia species. Differences observed in temporal and spectral characteristics of female and male signals enable species discrimination by PCA analyses. Insects that respond to heterospecific vibratory signals do not step forward to behaviors leading to copulation. Results suggest that species isolation takes place in both investigated Chinavia species at an early stage of mating behavior reducing reproductive interfer- ence and the probability of heterospecific mating. -

Dr. Frank G. Zalom

Award Category: Lifetime Achievement The Lifetime Achievement in IPM Award goes to an individual who has devoted his or her career to implementing IPM in a specific environment. The awardee must have devoted their career to enhancing integrated pest management in implementation, team building, and integration across pests, commodities, systems, and disciplines. New for the 9th International IPM Symposium The Lifetime Achievement winner will be invited to present his or other invited to present his or her own success story as the closing plenary speaker. At the same time, the winner will also be invited to publish one article on their success of their program in the Journal of IPM, with no fee for submission. Nominator Name: Steve Nadler Nominator Company/Affiliation: Department of Entomology and Nematology, University of California, Davis Nominator Title: Professor and Chair Nominator Phone: 530-752-2121 Nominator Email: [email protected] Nominee Name of Individual: Frank Zalom Nominee Affiliation (if applicable): University of California, Davis Nominee Title (if applicable): Distinguished Professor and IPM specialist, Department of Entomology and Nematology, University of California, Davis Nominee Phone: 530-752-3687 Nominee Email: [email protected] Attachments: Please include the Nominee's Vita (Nominator you can either provide a direct link to nominee's Vita or send email to Janet Hurley at [email protected] with subject line "IPM Lifetime Achievement Award Vita include nominee name".) Summary of nominee’s accomplishments (500 words or less): Describe the goals of the nominee’s program being nominated; why was the program conducted? What condition does this activity address? (250 words or less): Describe the level of integration across pests, commodities, systems and/or disciplines that were involved. -

Descriptions of Nymphal Instars of Thyanta Calceata (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 15 Number 4 - Winter 1982 Number 4 - Winter Article 2 1982 December 1982 Descriptions of Nymphal Instars of Thyanta Calceata (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) S. M. Paskewitz Southern Illinois University J. E. McPherson Southern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Paskewitz, S. M. and McPherson, J. E. 1982. "Descriptions of Nymphal Instars of Thyanta Calceata (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 15 (4) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol15/iss4/2 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Paskewitz and McPherson: Descriptions of Nymphal Instars of <i>Thyanta Calceata</i> (Hemip 1982 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 231 DESCRIPTIONS OF NYMPHAL INSTARS OF THYANTA CALCEATA (HEMIPTERA: PENTATOMJDAE) S. M. Paskewitz and J. E. McPherson I ABSTRACT The external anatomy of each of the five nymphal instars of Thyanta calceata is de scribed. Thyanta calceata (Say) ranges from New England south to Florida, and west to Michigan, Illinois. and }'lissouri (McPherson 1982). Much is known ofthe biology ofthis phytophagous stink bug including its life cycle and food plants (McPherson 1982). Of the immature stages. however. only the eggs (Oetting and Yonke 197/) have been described. Presented here are descriptions of the five nymphal instars. METHODS AND MATERIALS .symphs used for the descriptions were from F2 laboratory stock; the stock had originally been established with individuals collected July-August 1981, in Greene County and Craig head County. -

Sensitivity of Immature Thyanta Calceata (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) to Photoperiod As Reflected Yb Adult Color and Pubescence

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 11 Number 1 - Spring 1978 Number 1 - Spring 1978 Article 10 April 1978 Sensitivity of Immature Thyanta Calceata (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) to Photoperiod as Reflected yb Adult Color and Pubescence J. E. McPherson Southern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation McPherson, J. E. 1978. "Sensitivity of Immature Thyanta Calceata (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) to Photoperiod as Reflected yb Adult Color and Pubescence," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 11 (1) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol11/iss1/10 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. McPherson: Sensitivity of Immature <i>Thyanta Calceata</i> (Hemiptera: Penta THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST SENSITIVITY OF IMMATURE THYANTA CALCEATA (HEMIPTERA: PENTATOMIDAE) TO PHOTOPERIOD AS REFLECTED BY ADULT COLOR AND PUBESCENCE^ ABSTRACT Dimorphism in color and pubescence of adult Thyanta calceata, in response to 8L:16D and 16L:8D photoperiods, resulted from an accumulation of photoperiod effects on two or more immature stages. More immature stages were receptive to 8L:16D than to 16L:8D photoperiod influence. Thyanta calceata (Say) occurs from New England south to Florida and west to Illinois (Blatchley, 1926) and Missouri (Oetting and Yonke, 1971). Ruckes (1957) felt it was seasonally dimorphic, with brown "autumnal-vernal" adults clothed in long seta-like hairs and "summer" adults in short hairs (less than diameter of tibiae).