Anarchism: a History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

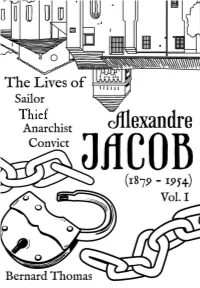

Bernard Thomas Volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M

Thief Jacob Alexandre Marius alias Escande Attila George Bonnot Féran Hard to Kill the Robber Bernard Thomas volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno First Published by Tchou Éditions 1970 This edition translated by Paul Sharkey footnotes translated by Laetitia Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno translated by Jean Weir Published in September 2010 by Elephant Editions and Bandit Press Elephant Editions Ardent Press 2013 introduction i the bandits 1 the agitator 37 introduction The impossibility of a perspective that is fully organized in all its details having been widely recognised, rigor and precision have disappeared from the field of human expectations and the need for order and security have moved into the sphere of desire. There, a last fortress built in fret and fury, it has established a foothold for the final battle. Desire is sacred and inviolable. It is what we hold in our hearts, child of our instincts and father of our dreams. We can count on it, it will never betray us. The newest graves, those that we fill in the edges of the cemeteries in the suburbs, are full of this irrational phenomenology. We listen to first principles that once would have made us laugh, assigning stability and pulsion to what we know, after all, is no more than a vague memory of a passing wellbeing, the fleeting wing of a gesture in the fog, the flapping morning wings that rapidly ceded to the needs of repetitiveness, the obsessive and disrespectful repetitiveness of the bureaucrat lurking within us in some dark corner where we select and codify dreams like any other hack in the dissecting rooms of repression. -

The Spanish Anarchists: the Heroic Years, 1868-1936

The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 the text of this book is printed on 100% recycled paper The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 s Murray Bookchin HARPER COLOPHON BOOKS Harper & Row, Publishers New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, London memoria de Russell Blackwell -^i amigo y mi compahero Hafold F. Johnson Library Ceirtef' "ampsliire College Anrteret, Massachusetts 01002 A hardcover edition of this book is published by Rree Life Editions, Inc. It is here reprinted by arrangement. THE SPANISH ANARCHISTS. Copyright © 1977 by Murray Bookchin. AH rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except in the case ofbrief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address ftee Life Editions, Inc., 41 Union Square West, New York, N.Y. 10003. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published 1978 ISBN: 0-06-090607-3 78 7980 818210 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 21 Contents OTHER BOOKS BY MURRAY BOOKCHIN Introduction ^ Lebensgefahrliche, Lebensmittel (1955) Prologue: Fanelli's Journey ^2 Our Synthetic Environment (1%2) I. The "Idea" and Spain ^7 Crisis in Our Qties (1965) Post-Scarcity Anarchism (1971) BACKGROUND MIKHAIL BAKUNIN 22 The Limits of the Qty (1973) Pour Une Sodete Ecologique (1976) II. The Topography of Revolution 32 III. The Beginning THE INTERNATIONAL IN SPAIN 42 IN PREPARATION THE CONGRESS OF 1870 51 THE LIBERAL FAILURE 60 T'he Ecology of Freedom Urbanization Without Cities IV. The Early Years 67 PROLETARIAN ANARCHISM 67 REBELLION AND REPRESSION 79 V. -

Télécharger L'inventaire En

Fonds Sembat-Agutte (XVIIe-1979) Guide (637AP/1-637AP/253, 637AP/AV/254-255, 637AP/256, CP/637AP/257- 258) Par C. Nau-Blin, C. Nougaret et O. Poncet Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 2004 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_003563 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé en 2012 par l'entreprise Numen dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) Préface Collaboration et remerciements Claire Blin-Nau, archiviste paléographe Pierre Jugie, conservateur en chef Christine Nougaret, conservateur général Hélène Cavalié, Fanny Lambert, Stéphane Reecht et Aurélie Thomas, élèves stagiaires de l'École nationale des chartes, Guillaume Cornille, stagiaire de l'université Paris I Pascal David, adjoint technique à la Section des archives privées avec la collaboration scientifique de Christian Phéline, éditeur des Cahiers noirs de Marcel Sembat avec la participation de Stéphane Le Flohic, adjoint technique, et Armande Perlot, secrétaire, Section des archives privées/Section ancienne revu, corrigé et complété par Pierre Jugie Nous exprimons notre sincère gratitude à toutes celles et tous ceux qui nous ont apporté leur aide et leurs conseils pour la rédaction de cet instrument de recherche, notamment : Françoise Aujogue, Sandrine Lacombe, Magali Lacousse, -

Anarchism in Greece

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Anarchism in Greece Antonios Vradis & Dimitrios K. Dalakoglou Antonios Vradis & Dimitrios K. Dalakoglou Anarchism in Greece 2009 Vradis, Antonios, and Dimitrios K. Dalakoglou. “Anarchism, Greece.” In The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present, edited by Immanuel Ness, 126–127. Vol. 1. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. usa.anarchistlibraries.net 2009 Contents 1876–1944 .......................... 5 1967–Present ......................... 6 References And Suggested Readings ............ 8 3 demonstrators, for example at the higher education students’ Greek anarchy stands among the largest and most active con- demonstration of March 1, 2007. temporary movements of its kind in the world. The first organized State violence and repression acted – to some extent – as a anarchist group in the country appeared as early as 1876. Near- greenhouse for anarchism, increasing its influence. Since the complete lack of anarchist activity between World War II and the 1980s Athens boasts two anarchist publishing houses (Free Press military dictatorship (1967–74) effectively divides the history of and International Library) and numerous regularly published mag- Greek anarchism into two distinct phases, 1876–1944 and 1967– azines at any given time, along with hundreds of brochures and present. poster campaigns every year. Squats have emerged and anarchist collectives have appeared all across the country. In parallel to a 1876–1944 mass anarchist movement, Greece witnesses the emergence of clandestine anarchist activity, primarily arson and casualty free Individual anarchists were politically active from the early 1860s explosions of symbolic targets. In January 2008 alone the country (Emanouil Dadaoglou, Amilcare Cipriani, Mikelis Avlihos), while saw more than ten actions of this kind. -

'The Italians and the IWMA'

Levy, Carl. 2018. ’The Italians and the IWMA’. In: , ed. ”Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth”. The First International in Global Perspective. 29 The Hague: Brill, pp. 207-220. ISBN 978-900-4335-455 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/23423/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ........................................... -

Anarcho-Syndicalism in the 20Th Century

Anarcho-syndicalism in the 20th Century Vadim Damier Monday, September 28th 2009 Contents Translator’s introduction 4 Preface 7 Part 1: Revolutionary Syndicalism 10 Chapter 1: From the First International to Revolutionary Syndicalism 11 Chapter 2: the Rise of the Revolutionary Syndicalist Movement 17 Chapter 3: Revolutionary Syndicalism and Anarchism 24 Chapter 4: Revolutionary Syndicalism during the First World War 37 Part 2: Anarcho-syndicalism 40 Chapter 5: The Revolutionary Years 41 Chapter 6: From Revolutionary Syndicalism to Anarcho-syndicalism 51 Chapter 7: The World Anarcho-Syndicalist Movement in the 1920’s and 1930’s 64 Chapter 8: Ideological-Theoretical Discussions in Anarcho-syndicalism in the 1920’s-1930’s 68 Part 3: The Spanish Revolution 83 Chapter 9: The Uprising of July 19th 1936 84 2 Chapter 10: Libertarian Communism or Anti-Fascist Unity? 87 Chapter 11: Under the Pressure of Circumstances 94 Chapter 12: The CNT Enters the Government 99 Chapter 13: The CNT in Government - Results and Lessons 108 Chapter 14: Notwithstanding “Circumstances” 111 Chapter 15: The Spanish Revolution and World Anarcho-syndicalism 122 Part 4: Decline and Possible Regeneration 125 Chapter 16: Anarcho-Syndicalism during the Second World War 126 Chapter 17: Anarcho-syndicalism After World War II 130 Chapter 18: Anarcho-syndicalism in contemporary Russia 138 Bibliographic Essay 140 Acronyms 150 3 Translator’s introduction 4 In the first decade of the 21st century many labour unions and labour feder- ations worldwide celebrated their 100th anniversaries. This was an occasion for reflecting on the past century of working class history. Mainstream labour orga- nizations typically understand their own histories as never-ending struggles for better working conditions and a higher standard of living for their members –as the wresting of piecemeal concessions from capitalists and the State. -

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions. In: Matthew S. Adams and Ruth Kinna, eds. Anarchism, 1914-1918: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 69-92. ISBN 9781784993412 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/20790/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] 85 3 Malatesta and the war interventionist debate 1914–17: from the ‘Red Week’ to the Russian revolutions Carl Levy This chapter will examine Errico Malatesta’s (1853–1932) position on intervention in the First World War. The background to the debate is the anti-militarist and anti-dynastic uprising which occurred in Italy in June 1914 (La Settimana Rossa) in which Malatesta was a key actor. But with the events of July and August 1914, the alliance of socialists, republicans, syndicalists and anarchists was rent asunder in Italy as elements of this coalition supported intervention on the side of the Entente and the disavowal of Italy’s treaty obligations under the Triple Alliance. Malatesta’s dispute with Kropotkin provides a focus for the anti-interventionist campaigns he fought internationally, in London and in Italy.1 This chapter will conclude by examining Malatesta’s discussions of the unintended outcomes of world war and the challenges and opportunities that the fracturing of the antebellum world posed for the international anarchist movement. -

Charlotte Wilson, the ''Woman Question'', and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism

IRSH, Page 1 of 34. doi:10.1017/S0020859011000757 r 2011 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Charlotte Wilson, the ‘‘Woman Question’’, and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism S USAN H INELY Department of History, State University of New York at Stony Brook E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: Recent literature on radical movements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has re-cast this period as a key stage of contemporary globali- zation, one in which ideological formulations and radical alliances were fluid and did not fall neatly into the categories traditionally assigned by political history. The following analysis of Charlotte Wilson’s anarchist political ideas and activism in late Victorian Britain is an intervention in this new historiography that both supports the thesis of global ideological heterogeneity and supplements it by revealing the challenge to sexual hierarchy that coursed through many of these radical cross- currents. The unexpected alliances Wilson formed in pursuit of her understanding of anarchist socialism underscore the protean nature of radical politics but also show an over-arching consensus that united these disparate groups, a common vision of the socialist future in which the fundamental but oppositional values of self and society would merge. This consensus arguably allowed Wilson’s gendered definition of anarchism to adapt to new terms as she and other socialist women pursued their radical vision as activists in the pre-war women’s movement. INTRODUCTION London in the last decades of the nineteenth century was a global crossroads and political haven for a large number of radical activists and theorists, many of whom were identified with the anarchist school of socialist thought. -

Histoire Des Bourses Du Travail Origine - Institutions - Avenir

Anti.mythes Anti.mythes HISTOIRE DES BOURSES DU TRAVAIL ORIGINE - INSTITUTIONS - AVENIR ----- Ouvrage posthume de Fernand PELLOUTIER Secrétaire général de la Fédération nationale des Bourses du Travail de France et des Colonies Brochure numérique gratuite n°3 d’Anti.mythes: «Histoire des Bourses du Travail». Brochure numérique gratuite n°3 d’Anti.mythes: «Histoire des Bourses du Travail». Page 2 SOMMAIRE: En guise d’avant-propos, par Anti.mythes. 3 «Fernand PELLOUTIER», par Paul DELESALLE, dans Les Temps nouveaux n°48 du 5 23 mars 1901. Notice biographique sur Fernand PELLOUTIER par Victor DAVE. 7 Histoire des Bourses du Travail: Ch. 1: Après la Commune 13 Ch. 2: Les «Partis ouvriers» et les Syndicats 21 Ch. 3: Naissance des Bourses du Travail 24 Ch. 4: Historique des Bourses du Travail 30 Ch. 5: Comment se crée une Bourse du Travail 33 Ch. 6: L’œuvre des Bourses du Travail 36 1- Service de la Mutualité 37 1- Le placement 37 2- Le secours de chômage 38 3- Le viaticum, ou secours aux ouvriers de passage 38 4- L’Offi ce national ouvrier de statistiques et de placement 40 5- Caisses diverses 46 2- Service de l’Enseignement 47 1- Les bibliothèques 47 2- Les Musées du Travail 48 3- Les offi ces de renseignements 49 4- La presse corporative 50 5- L’enseignement 51 3- Le service de la propagande 54 1- Propagande industrielle 55 2- Propagande agraire 55 3- Propagande maritime 58 4- L’action coopérative 61 Ch. 7: Le Comité fédéral des Bourses du Travail 65 Ch. 8: Conjectures sur l’avenir des Bourses du Travail, et conclusion. -

Histoire Des Bourses Du Travail : Origine, Institutions, Avenir / Ouvrage Posthume De Fernand Pelloutier

Histoire des Bourses du travail : origine, institutions, avenir / ouvrage posthume de Fernand Pelloutier,... ; préf. par [...] Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France Pelloutier, Fernand. Histoire des Bourses du travail : origine, institutions, avenir / ouvrage posthume de Fernand Pelloutier,... ; préf. par Georges Sorel ; [Notice biographique sur Fernand Pelloutier] par Victor Dave. 1921. 1/ Les contenus accessibles sur le site Gallica sont pour la plupart des reproductions numériques d'oeuvres tombées dans le domaine public provenant des collections de la BnF. Leur réutilisation s'inscrit dans le cadre de la loi n°78-753 du 17 juillet 1978 : - La réutilisation non commerciale de ces contenus est libre et gratuite dans le respect de la législation en vigueur et notamment du maintien de la mention de source. - La réutilisation commerciale de ces contenus est payante et fait l'objet d'une licence. Est entendue par réutilisation commerciale la revente de contenus sous forme de produits élaborés ou de fourniture de service. CLIQUER ICI POUR ACCÉDER AUX TARIFS ET À LA LICENCE 2/ Les contenus de Gallica sont la propriété de la BnF au sens de l'article L.2112-1 du code général de la propriété des personnes publiques. 3/ Quelques contenus sont soumis à un régime de réutilisation particulier. Il s'agit : - des reproductions de documents protégés par un droit d'auteur appartenant à un tiers. Ces documents ne peuvent être réutilisés, sauf dans le cadre de la copie privée, sans l'autorisation préalable du titulaire des droits. - des reproductions de documents conservés dans les bibliothèques ou autres institutions partenaires. Ceux-ci sont signalés par la mention Source gallica.BnF.fr / Bibliothèque municipale de .. -

Proquest Dissertations

RICE UNIVERSITY The Struggle for Modern Athens: Unconventional Citizens and the Shaping of a New Political Reality by Othon Alexandrakis A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: ttill g^ jLS^x£ft //t/T- Jafmelames Faubi((nFaubioV, Professor, Anthropology Amy Ninetto, Assistant Professor^Anthropology Lora Wildenthal, Associate Professor, History Eugenia Georges, Professor, Anthropology HOUSTON, TEXAS FEBRUARY 2010 UMI Number: 3421434 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3421434 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Copyright Othon Alexandrakis 2010 ABSTRACT The Struggle for Modern Athens: Unconventional Citizens and the Shaping of a New Political Reality by Othon Alexandrakis The dissertation is based on over one-and-a-half years of ethnographic field research conducted in Athens, Greece, among various diverse populations practicing unconventional modes of citizenship, that is, citizenship imagined and practiced in contradiction to traditional, prescribed, or sanctioned civil identities. I focus specifically on newcomer undocumented migrant populations from Africa, the broadly segregated and disenfranchised Roma (Gypsy) community, and the rapidly growing anti- establishment youth population.