Evaluation of Restoration Techniques and Management Practices of Tule Pertaining to Eco-Cultural Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improved Conservation Plant Materials Released by NRCS and Cooperators Through December 2014

Natural Resources Conservation Service Improved Conservation Plant Materials Released by Plant Materials Program NRCS and Cooperators through December 2014 Page intentionally left blank. Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Materials Program Improved Conservation Plant Materials Released by NRCS and Cooperators Through December 2014 Norman A. Berg Plant Materials Center 8791 Beaver Dam Road Building 509, BARC-East Beltsville, Maryland 20705 U.S.A. Phone: (301) 504-8175 prepared by: Julie A. DePue Data Manager/Secretary [email protected] John M. Englert Plant Materials Program Leader [email protected] January 2015 Visit our Website: http://Plant-Materials.nrcs.usda.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS Topics Page Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Types of Plant Materials Releases ........................................................................................................................2 Sources of Plant Materials ....................................................................................................................................3 NRCS Conservation Plants Released in 2013 and 2014 .......................................................................................4 Complete Listing of Conservation Plants Released through December 2014 ......................................................6 Grasses ......................................................................................................................................................8 -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Ley, So the Still Deeper Cañon of Lower Two Miles,That Is, Beyond Rather Than

THE CANON OF YOSEMITE 87 As Merced Cañon forms the southeast branch of Yosemite Val- ley, so the still deeper cañon of Tenaya Creek isits northeastern arm.Here the glacial story is less plain, and on first sight, from the heights on either side, it might be overlooked.For above the cañon's lower two miles,that is, beyond the foot of Mt. Watkins,it crowds to a narrow box-cañon between that great cliff and the steep incline of Clouds Rest.This might seem to be a V-shaped, stream-cut gorge, rather than to have the broader bottom commonly left by a glacier. But alittle exploration discovers glacial footprints in the terminal moraines and the lakes and filled lake-beds,withfineconnecting waterfalls, that mark aglacier's descent from the Cathedral Peak Range, south of the Tuolumne. We Overhung at Summit of the Half Dont,-. nrart have hardly entered the cañon, in- a tulle above the Valley floor nn.l Tena-u deed, before we are reminded of (allan.El Caption Is seen in the tllatanee. El Capitan moraine and the enclosed Yosemite Lake. A similar boulder ridge, thrown across the cañon here, is traversed by the road as it carries visitors on their early morning trips to see the sunrise reflections in Mirror Lake.This lakelet evidently occupies the lowermost of the glacial steps.It is a mere reminder of its former size, the delta of Tenaya Creek having stolen a mile from its upper end.Farther up the cañon, below and above Mt. Watkins, stream sediment has already turned similar lakes into meadows. -

NJ Native Plants - USDA

NJ Native Plants - USDA Scientific Name Common Name N/I Family Category National Wetland Indicator Status Thermopsis villosa Aaron's rod N Fabaceae Dicot Rubus depavitus Aberdeen dewberry N Rosaceae Dicot Artemisia absinthium absinthium I Asteraceae Dicot Aplectrum hyemale Adam and Eve N Orchidaceae Monocot FAC-, FACW Yucca filamentosa Adam's needle N Agavaceae Monocot Gentianella quinquefolia agueweed N Gentianaceae Dicot FAC, FACW- Rhamnus alnifolia alderleaf buckthorn N Rhamnaceae Dicot FACU, OBL Medicago sativa alfalfa I Fabaceae Dicot Ranunculus cymbalaria alkali buttercup N Ranunculaceae Dicot OBL Rubus allegheniensis Allegheny blackberry N Rosaceae Dicot UPL, FACW Hieracium paniculatum Allegheny hawkweed N Asteraceae Dicot Mimulus ringens Allegheny monkeyflower N Scrophulariaceae Dicot OBL Ranunculus allegheniensis Allegheny Mountain buttercup N Ranunculaceae Dicot FACU, FAC Prunus alleghaniensis Allegheny plum N Rosaceae Dicot UPL, NI Amelanchier laevis Allegheny serviceberry N Rosaceae Dicot Hylotelephium telephioides Allegheny stonecrop N Crassulaceae Dicot Adlumia fungosa allegheny vine N Fumariaceae Dicot Centaurea transalpina alpine knapweed N Asteraceae Dicot Potamogeton alpinus alpine pondweed N Potamogetonaceae Monocot OBL Viola labradorica alpine violet N Violaceae Dicot FAC Trifolium hybridum alsike clover I Fabaceae Dicot FACU-, FAC Cornus alternifolia alternateleaf dogwood N Cornaceae Dicot Strophostyles helvola amberique-bean N Fabaceae Dicot Puccinellia americana American alkaligrass N Poaceae Monocot Heuchera americana -

The Role of Seed Bank and Germination Dynamics in the Restoration of a Tidal Freshwater Marsh in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta Taylor M

SEPTEMBER 2019 Sponsored by the Delta Science Program and the UC Davis Muir Institute RESEARCH The Role of Seed Bank and Germination Dynamics in the Restoration of a Tidal Freshwater Marsh in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta Taylor M. Sloey,1,2 Mark W. Hester2 ABSTRACT enhanced using a pre-germination cold exposure, Liberty Island, California, is a historical particularly for species of concern for wetland freshwater tidal wetland that was converted restoration. The cold stratification study showed to agricultural fields in the early 1900s. that longer durations of pre-germination cold Liberty Island functioned as farmland until an enhanced germination in Schoenoplectus acutus, accidental levee break flooded the area in 1997, but reduced germination in Schoenoplectus inadvertently restoring tidal marsh hydrology. californicus, and had no effect on Typha latifolia. Since then, wetland vegetation has naturally Overall, germination of S. californicus and recolonized part of the site. We conducted a seed S. acutus was much lower than T. latifolia. Our bank assay at the site and found that despite a findings suggest that seeding may not be an lack of germination or seedling recruitment at effective restoration technique for Schoenoplectus the site, the seed bank contained a diverse plant spp., and, to improve restoration techniques, community, indicating that the site’s continuous further study is needed to more comprehensively flooding was likely suppressing germination. understand the reproduction ecology of important Additionally, the frequency -

Gazetteer of Surface Waters of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTI8 SMITH, DIEECTOE WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 296 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS OF CALIFORNIA PART II. SAN JOAQUIN RIVER BASIN PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OP JOHN C. HOYT BY B. D. WOOD In cooperation with the State Water Commission and the Conservation Commission of the State of California WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1912 NOTE. A complete list of the gaging stations maintained in the San Joaquin River basin from 1888 to July 1, 1912, is presented on pages 100-102. 2 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS IN SAN JOAQUIN RIYER BASIN, CALIFORNIA. By B. D. WOOD. INTRODUCTION. This gazetteer is the second of a series of reports on the* surf ace waters of California prepared by the United States Geological Survey under cooperative agreement with the State of California as repre sented by the State Conservation Commission, George C. Pardee, chairman; Francis Cuttle; and J. P. Baumgartner, and by the State Water Commission, Hiram W. Johnson, governor; Charles D. Marx, chairman; S. C. Graham; Harold T. Powers; and W. F. McClure. Louis R. Glavis is secretary of both commissions. The reports are to be published as Water-Supply Papers 295 to 300 and will bear the fol lowing titles: 295. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part I, Sacramento River basin. 296. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part II, San Joaquin River basin. 297. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part III, Great Basin and Pacific coast streams. 298. Water resources of California, Part I, Stream measurements in the Sacramento River basin. -

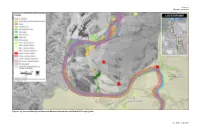

Botanical Resources and Wetlands Technical Report

Chapter 1 Affected Environment Figure 1-3g. Sensitive Biological Resources Between Shasta Dam and Red Bluff Pumping Plant 1-45 Draft – June 2013 Shasta Lake Water Resources Investigation Biological Resources Appendix – Botanical Resources and Wetlands Technical Report This page left blank intentionally. 1-46 Draft – June 2013 Chapter 1 Affected Environment Figure 1-3h. Sensitive Biological Resources Between Shasta Dam and Red Bluff Pumping Plant 1-47 Draft – June 2013 Shasta Lake Water Resources Investigation Biological Resources Appendix – Botanical Resources and Wetlands Technical Report This page left blank intentionally. 1-48 Draft – June 2013 Chapter 1 Affected Environment Figure 1-3i. Sensitive Biological Resources Between Shasta Dam and Red Bluff Pumping Plant 1-49 Draft – June 2013 Shasta Lake Water Resources Investigation Biological Resources Appendix – Botanical Resources and Wetlands Technical Report This page left blank intentionally. 1-50 Draft – June 2013 Chapter 1 Affected Environment Figure 1-3j. Sensitive Biological Resources Between Shasta Dam and Red Bluff Pumping Plant 1-51 Draft – June 2013 Shasta Lake Water Resources Investigation Biological Resources Appendix – Botanical Resources and Wetlands Technical Report This page left blank intentionally. 1-52 Draft – June 2013 Chapter 1 Affected Environment 1 Valley Oak Woodland This habitat type consists of an open savanna of 2 valley oak (Quercus lobata) trees and an annual grassland understory. Valley 3 oak is typically the only tree species present and shrubs are generally absent 4 except for occasional poison oak. Canopy cover rarely exceeds 30–40 percent in 5 valley oak woodland. This community occupies the highest portions of the 6 floodplain terrace where flooding is infrequent and shallow. -

Hall's Bulrush Habitat Characterization and Monitoring

Hall’s Bulrush Habitat Characterization and Monitoring Project 2003 Report Prepared by: Phyllis J. Higman and Michael R. Penskar Michigan Natural Features Inventory P.O. Box 30444 Lansing, MI 48909-7944 For: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 Office Minneapolis, MN March 31, 2004 Report Number 2004-14 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Study Site ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Methods ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Population and Vegetation Monitoring ................................................................................................... 1 Floristic Characterization ....................................................................................................................... 5 Well Monitoring ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Soil Characterization .............................................................................................................................. 5 Seed Bank Characterization .................................................................................................................... 5 Photo Monitoring -

Sources Dicken, S

Tules By Frank A. Lang In Oregon and much of the western United States, tule is the common name for two species of emergent plants that grow in shallow water of marshes, muddy shores, and lakes. These sedges (family Cyperaceae) are named hard-stemmed (Schoenoplectus acutus var. occidentalis) and soft-stemmed (S. tabernaemontani) bulrushes. Tule, a Spanish name, is based on tollin, of Nahurtl Native American lingustic stock, meaning a rush. Older botanical literature places these bulrushes in Scirpus, a closely related genus with various species names attached. Tule, the basis of the name of the Klamath basin town of Tulelake in northern California, was named after the extensive shallow Tule Lake (not to be confused with ancient Lake Tulare in the Great Valley of California). Present-day Tule Lake is the remainder of Pluvial Lake Modoc, which filled the Klamath Basin during the Pleistocene. As climates changed, ancient Lake Modoc shrank, forming Upper and Lower Klamath Lakes and Tule Lake. Irrigation projects reduced the lakes to their present size. Oregonians are probably most familiar with the extensive marshes on the margins and in the shallows of the great interior Klamath Lakes and Marsh and Malheur lakes. The tall (three- to six-foot), round, green stems are topped with clusters of brown, seed-producing spikelets of flowers. This contrasts with the cattail (Typha latifolia, family Typhaceae), another common emergent aquatic plant with flat leaves and characteristic flower clusters at the end of a leafless round shoot. Tule bulrushes arise from an extensive rhizome system that forms vegetative mats with cattails and other graminoids (grasses and grass-like plants, including other sedges and rushes). -

Cyperaceae of Alberta

AN ILLUSTRATED KEY TO THE CYPERACEAE OF ALBERTA Compiled and writen by Linda Kershaw and Lorna Allen April 2019 © Linda J. Kershaw & Lorna Allen This key was compiled using information primarily from and the Flora North America Association (2008), Douglas et al. (1998), and Packer and Gould (2017). Taxonomy follows VASCAN (Brouillet, 2015). The main references are listed at the end of the key. Please try the key this summer and let us know if there are ways in which it can be improved. Over the winter, we hope to add illustrations for most of the entries. The 2015 S-ranks of rare species (S1; S1S2; S2; S2S3; SU, according to ACIMS, 2015) are noted in superscript ( S1; S2;SU) after the species names. For more details go to the ACIMS web site. Similarly, exotic species are followed by a superscript X, XX if noxious and XXX if prohibited noxious (X; XX; XXX) according to the Alberta Weed Control Act (2016). CYPERACEAE SedgeFamily Key to Genera 1b 01a Flowers either ♂ or ♀; ovaries/achenes enclosed in a sac-like or scale-like structure 1a (perigynium) .....................Carex 01b Flowers with both ♂ and ♀ parts (sometimes some either ♂ or ♀); ovaries/achenes not in a perigynium .........................02 02a Spikelets somewhat fattened, with keeled scales in 2 vertical rows, grouped in ± umbrella- shaped clusters; fower bristles (perianth) 2a absent ....................... Cyperus 02b Spikelets round to cylindrical, with scales 2b spirally attached, variously arranged; fower bristles usually present . 03 03a Achenes tipped with a rounded protuberance (enlarged style-base; tubercle) . 04 03b Achenes without a tubercle (achenes 3a 3b often beaked, but without an enlarged protuberence) .......................05 04a Spikelets single; stems leafess . -

Checklist Flora of the Former Carden Township, City of Kawartha Lakes, on 2016

Hairy Beardtongue (Penstemon hirsutus) Checklist Flora of the Former Carden Township, City of Kawartha Lakes, ON 2016 Compiled by Dale Leadbeater and Anne Barbour © 2016 Leadbeater and Barbour All Rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or database, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, without written permission of the authors. Produced with financial assistance from The Couchiching Conservancy. The City of Kawartha Lakes Flora Project is sponsored by the Kawartha Field Naturalists based in Fenelon Falls, Ontario. In 2008, information about plants in CKL was scattered and scarce. At the urging of Michael Oldham, Biologist at the Natural Heritage Information Centre at the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Dale Leadbeater and Anne Barbour formed a committee with goals to: • Generate a list of species found in CKL and their distribution, vouchered by specimens to be housed at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, making them available for future study by the scientific community; • Improve understanding of natural heritage systems in the CKL; • Provide insight into changes in the local plant communities as a result of pressures from introduced species, climate change and population growth; and, • Publish the findings of the project . Over eight years, more than 200 volunteers and landowners collected almost 2000 voucher specimens, with the permission of landowners. Over 10,000 observations and literature records have been databased. The project has documented 150 new species of which 60 are introduced, 90 are native and one species that had never been reported in Ontario to date. -

Flora-Lab-Manual.Pdf

LabLab MManualanual ttoo tthehe Jane Mygatt Juliana Medeiros Flora of New Mexico Lab Manual to the Flora of New Mexico Jane Mygatt Juliana Medeiros University of New Mexico Herbarium Museum of Southwestern Biology MSC03 2020 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM, USA 87131-0001 October 2009 Contents page Introduction VI Acknowledgments VI Seed Plant Phylogeny 1 Timeline for the Evolution of Seed Plants 2 Non-fl owering Seed Plants 3 Order Gnetales Ephedraceae 4 Order (ungrouped) The Conifers Cupressaceae 5 Pinaceae 8 Field Trips 13 Sandia Crest 14 Las Huertas Canyon 20 Sevilleta 24 West Mesa 30 Rio Grande Bosque 34 Flowering Seed Plants- The Monocots 40 Order Alistmatales Lemnaceae 41 Order Asparagales Iridaceae 42 Orchidaceae 43 Order Commelinales Commelinaceae 45 Order Liliales Liliaceae 46 Order Poales Cyperaceae 47 Juncaceae 49 Poaceae 50 Typhaceae 53 Flowering Seed Plants- The Eudicots 54 Order (ungrouped) Nymphaeaceae 55 Order Proteales Platanaceae 56 Order Ranunculales Berberidaceae 57 Papaveraceae 58 Ranunculaceae 59 III page Core Eudicots 61 Saxifragales Crassulaceae 62 Saxifragaceae 63 Rosids Order Zygophyllales Zygophyllaceae 64 Rosid I Order Cucurbitales Cucurbitaceae 65 Order Fabales Fabaceae 66 Order Fagales Betulaceae 69 Fagaceae 70 Juglandaceae 71 Order Malpighiales Euphorbiaceae 72 Linaceae 73 Salicaceae 74 Violaceae 75 Order Rosales Elaeagnaceae 76 Rosaceae 77 Ulmaceae 81 Rosid II Order Brassicales Brassicaceae 82 Capparaceae 84 Order Geraniales Geraniaceae 85 Order Malvales Malvaceae 86 Order Myrtales Onagraceae