Metalwork and Material Culture in the Islamic World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreign Policy Trends in the GCC States

Autumn 2017 A Publication based at St Antony’s College Foreign Policy Trends in the GCC States Featuring H.E. Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al-Thani Minister of Foreign Affairs State of Qatar H.E. Sayyid Badr bin Hamad Albusaidi Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sultanate of Oman H.E. Ambassador Michele Cervone d’Urso Head of Delegation to Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman & Qatar European Union Foreword by Kristian Coates Ulrichsen OxGAPS | Oxford Gulf & Arabian Peninsula Studies Forum OxGAPS is a University of Oxford platform based at St Antony’s College promoting interdisciplinary research and dialogue on the pressing issues facing the region. Senior Member: Dr. Eugene Rogan Committee: Chairman & Managing Editor: Suliman Al-Atiqi Vice Chairman & Co-Editor: Adel Hamaizia Editor: Adam Rasmi Associate Editor: Rana AlMutawa Research Associate: Lolwah Al-Khater Research Associate: Jalal Imran Head of Outreach: Mohammed Al-Dubayan Broadcasting & Archiving Officer: Oliver Ramsay Gray Copyright © 2017 OxGAPS Forum All rights reserved Autumn 2017 Gulf Affairs is an independent, non-partisan journal organized by OxGAPS, with the aim of bridging the voices of scholars, practitioners and policy-makers to further knowledge and dialogue on pressing issues, challenges and opportunities facing the six member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessar- ily represent those of OxGAPS, St Antony’s College or the University of Oxford. Contact Details: OxGAPS Forum 62 Woodstock Road Oxford, OX2 6JF, UK Fax: +44 (0)1865 595770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.oxgaps.org Design and Layout by B’s Graphic Communication. -

Le Musée Aga Khan Célèbre La Créativité Et Les Contributions Artistiques Des Immigrants Au Cours D’Une Saison Qui Fait La Part Belle À L’Immigration

Le Musée Aga Khan célèbre la créativité et les contributions artistiques des immigrants au cours d’une saison qui fait la part belle à l’immigration Cinquante-et-un artistes plasticiens, 15 spectacles et 10 orateurs représentant plus de 50 pays seront à l’honneur lors de cette saison dédiée à l’immigration. Toronto, Canada, le 4 mars 2020 - Loin des gros-titres sur l’augmentation de la migration dans le monde, le Musée Aga Khan célèbrera les contributions artistiques des immigrants et des réfugiés à l’occasion de sa nouvelle saison. Cette saison dédiée à l’immigration proposera trois expositions mettant en lumière la créativité des migrants et les contributions artistiques qu’ils apportent tout autour du monde. Aux côtés d’artistes et de leaders d’opinion venant du monde entier, ces expositions d’avant-garde présenteront des individus remarquables qui utilisent l’art et la culture pour surmonter l’adversité, construire leurs vies et enrichir leurs communautés malgré les déplacements de masse, le changement climatique et les bouleversements économiques. « À l’heure où la migration dans le monde est plus importante que jamais, nous, au Musée Aga Khan, pensons qu’il est de notre devoir de réfuter ces rumeurs qui dépeignent les immigrants et les réfugiés comme une menace pour l’intégrité de nos communautés », a déclaré Henry S. Kim, administrateur du Musée Aga Khan. « En tant que Canadiens, nous bénéficions énormément de l’arrivée d’immigrants et des nouveaux regards qu’ils apportent. En saisissant les occasions qui se présentent à eux au mépris de l’adversité, ils incarnent ce qu’il y a de mieux dans l’esprit humain. -

Islamic Art from the Collection, Oct. 23, 2020 - Dec

It Comes in Many Forms: Islamic Art from the Collection, Oct. 23, 2020 - Dec. 18, 2021 This exhibition presents textiles, decorative arts, and works on paper that show the breadth of Islamic artistic production and the diversity of Muslim cultures. Throughout the world for nearly 1,400 years, Islam’s creative expressions have taken many forms—as artworks, functional objects and tools, decoration, fashion, and critique. From a medieval Persian ewer to contemporary clothing, these objects explore migration, diasporas, and exchange. What makes an object Islamic? Does the artist need to be a practicing Muslim? Is being Muslim a religious expression or a cultural one? Do makers need to be from a predominantly Muslim country? Does the subject matter need to include traditionally Islamic motifs? These objects, a majority of which have never been exhibited before, suggest the difficulty of defining arts from a transnational religious viewpoint. These exhibition labels add honorifics whenever important figures in Islam are mentioned. SWT is an acronym for subhanahu wa-ta'ala (glorious and exalted is he), a respectful phrase used after every mention of Allah (God). SAW is an acronym for salallahu alayhi wa-sallam (may the blessings and the peace of Allah be upon him), used for the Prophet Muhammad, the founder and last messenger of Islam. AS is an acronym for alayhi as-sallam (peace be upon him), and is used for all other prophets before him. Tayana Fincher Nancy Elizabeth Prophet Fellow Costume and Textiles Department RISD Museum CHECKLIST OF THE EXHIBITION Spanish Tile, 1500s Earthenware with glaze 13.5 x 14 x 2.5 cm (5 5/16 x 5 1/2 x 1 inches) Gift of Eleanor Fayerweather 57.268 Heavily chipped on its surface, this tile was made in what is now Spain after the fall of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada (1238–1492). -

Configurations of the Indic States System

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 34 Number 34 Spring 1996 Article 6 4-1-1996 Configurations of the Indic States System David Wilkinson University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Wilkinson, David (1996) "Configurations of the Indic States System," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 34 : No. 34 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol34/iss34/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Wilkinson: Configurations of the Indic States System 63 CONFIGURATIONS OF THE INDIC STATES SYSTEM David Wilkinson In his essay "De systematibus civitatum," Martin Wight sought to clari- fy Pufendorfs concept of states-systems, and in doing so "to formulate some of the questions or propositions which a comparative study of states-systems would examine." (1977:22) "States system" is variously defined, with variation especially as to the degrees of common purpose, unity of action, and mutually recognized legitima- cy thought to be properly entailed by that concept. As cited by Wight (1977:21-23), Heeren's concept is federal, Pufendorfs confederal, Wight's own one rather of mutuality of recognized legitimate independence. Montague Bernard's minimal definition—"a group of states having relations more or less permanent with one another"—begs no questions, and is adopted in this article. Wight's essay poses a rich menu of questions for the comparative study of states systems. -

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY in CAIRO School of Humanities And

1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. Thank you for your patience, understanding and endless love. I am forever, indebted to you. I would like to thank my family and friends whose interest in the field and questions pushed me to find out more. Aziz, my brother, thank you for your questions and criticism, they only pushed me to be better at something I love to do. Zeina, we will explore this world of architecture together some day, thank you for listening and asking questions that only pushed me forward I love you. Alya’a and the Friday morning tours, best mornings of my adult life. Iman, thank you for listening to me ranting and complaining when I thought I’d never finish, thank you for pushing me. Salma, with me every step of the way, thank you for encouraging me always. Adham abu-elenin, thank you for your time and photography. -

The Sultan, the Tyrant, and the Hero: Changing Medieval Perceptions of Al-Zahir Baybars (MSR IV, 2000)

AMINA A. ELBENDARY AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO The Sultan, The Tyrant, and The Hero: Changing Medieval Perceptions of al-Z˛a≠hir Baybars* As the true founder of the Mamluk state, al-Z˛a≠hir Baybars is one of the most important sultans of Egypt and Syria. This has prompted many medieval writers and historians to write about his reign. Their perceptions obviously differed and their reconstructions of his reign draw different and often conflicting images. In this article I propose to examine and compare the various perceptions that different writers had of Baybars's life and character. Each of these writers had his own personal biases and his own purposes for writing about Baybars. The backgrounds against which they each lived and worked deeply influenced their writings. This led them to emphasize different aspects of his personality and legacy and to ignore others. Comparing these perceptions will demonstrate how the historiography of Baybars was used to make different political arguments concerning the sultan, the Mamluk regime, and rulership in general. I have used different representative examples of thirteenth- to fifteenth-century histories, chronicles, and biographical dictionaries in compiling this material. I have also compared these scholarly writings to the popular folk epic S|rat al-Z˛a≠hir Baybars. In his main official biography, written by Muh˛y| al-D|n ibn ‘Abd al-Z˛a≠hir, Baybars is presented as an ideal sultan. By contrast, works written after the sultan's day show more ambivalent attitudes towards him. Some fourteenth-century writers, like Sha≠fi‘ ibn ‘Al|, Baybars al-Mans˝u≠r|, and al-Nuwayr|, who were influenced by the regime of al-Na≠s˝ir Muh˛ammad, tend to place more emphasis on his despotic actions. -

Early Islamic Architecture in Iran

EARLY ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE IN IRAN (637-1059) ALIREZA ANISI Ph.D. THESIS THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH 2007 To My wife, and in memory of my parents Contents Preface...........................................................................................................iv List of Abbreviations.................................................................................vii List of Plates ................................................................................................ix List of Figures .............................................................................................xix Introduction .................................................................................................1 I Historical and Cultural Overview ..............................................5 II Legacy of Sasanian Architecture ...............................................49 III Major Feature of Architecture and Construction ................72 IV Decoration and Inscriptions .....................................................114 Conclusion .................................................................................................137 Catalogue of Monuments ......................................................................143 Bibliography .............................................................................................353 iii PREFACE It is a pleasure to mention the help that I have received in writing this thesis. Undoubtedly, it was my great fortune that I benefited from the supervision of Robert Hillenbrand, whose comments, -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

Arta 2005.001

ARTA 2005.001 St John Simpson - The British Museum Making their mark: Foreign travellers at Persepolis The ruins at Persepolis continue to fascinate scholars not least through the perspective of the early European travellers’ accounts. Despite being the subject of considerable study, much still remains to be discovered about this early phase of the history of archaeology in Iran. The early published literature has not yet been exhausted; manuscripts, letters, drawings and sculptures continue to emerge from European collections, and a steady trickle of further discoveries can be predicted. One particularly rich avenue lies in further research into the personal histories of individuals who are known to have been resident in or travelling through Iran, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries. These sources have value not only in what may pertain to the sites or antiquities, but they also add useful insights into the political and socio-economic situation within Iran during this period (Wright 1998; 1999; Simpson in press; forthcoming). The following paper offers some research possibilities by focusing on the evidence of the Achemenet janvier 2005 1 ARTA 2005.001 Fig. 1: Gate of All Nations graffiti left by some of these travellers to the site. Some bio- graphical details have been added where considered appro- priate but many of these individuals deserve a level of detailed research lying beyond the scope of this preliminary survey. Achemenet janvier 2005 2 ARTA 2005.001 The graffiti have attracted the attention of many visitors to the site, partly because of their visibility on the first major building to greet visitors to the site (Fig. -

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven Mediävistischer Forschung

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 5 Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Textile Inscriptions on Royal Garments from Norman Sicily Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) ISBN 978-3-11-053202-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-053387-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-053212-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Satzstudio Borngräber, Dessau-Roßlau Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Preface — IX Introduction — XI Chapter I Shaping Perceptions: Reading and Interpreting the Norman Arabic Textile Inscriptions — 1 1 Arabic-Inscribed Textiles from Norman and Hohenstaufen Sicily — 2 2 Inscribed Textiles and Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts — 43 3 Historical Receptions of the Ceremonial Garments from Norman Sicily — 51 4 Approaches to Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts: Methodological Considerations — 64 Chapter II An Imported Ornament? Comparing the Functions -

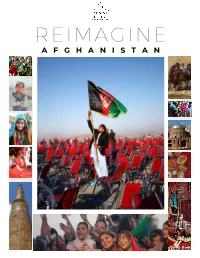

Reimagine a F G H a N I S T a N

REIMAGINE A F G H A N I S T A N A N I N I T I A T I V E B Y R A I S I N A H O U S E REIMAGINE A F G H A N I S T A N INTRODUCTION . Afghanistan equals Culture, heritage, music, poet, spirituality, food & so much more. The country had witnessed continuous violence for more than 4 ................................................... decades & this has in turn overshadowed the rich cultural heritage possessed by the country, which has evolved through mellinnias of Cultural interaction & evolution. Reimagine Afghanistan as a digital magazine is an attempt by Raisina House to explore & portray that hidden side of Afghanistan, one that is almost always overlooked by the mainstream media, the side that is Humane. Afghanistan is rich in Cultural Heritage that has seen mellinnias of construction & destruction but has managed to evolve to the better through the ages. Issued as part of our vision project "Rejuvenate Afghanistan", the magazine is an attempt to change the existing perception of Afghanistan as a Country & a society bringing forward that there is more to the Country than meets the eye. So do join us in this journey to explore the People, lifestyle, Art, Food, Music of this Adventure called Afghanistan. C O N T E N T S P A G E 1 AFGHANISTAN COUNTRY PROFILE P A G E 2 - 4 PEOPLE ETHNICITY & LANGUAGE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 5 - 7 ART OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 8 ARTISTS OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 9 WOOD CARVING IN AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 0 GLASS BLOWING IN AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 1 CARPETS OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 2 CERAMIC WARE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 3 - 1 4 FAMOUS RECIPES OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 5 AFGHANI POETRY P A G E 1 6 ARCHITECTURE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 7 REIMAGINING AFGHANISTAN THROUGH CINEMA P A G E 1 8 AFGHANI MOVIE RECOMMENDATION A B O U T A F G H A N I S T A N Afghanistan Country Profile: The Islamic Republic of Afghanistan is a landlocked country situated between the crossroads of Western, Central, and Southern Asia and is at the heart of the continent.