The Steagles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF of This Issue

MITF's vThe Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Cloudy, showers, 45°F (7°C) Newspaper :, Tonight: Fog, showers, 35°F (I°C) . 2 _ Tomorrow: Cool, showers, 42°F (6°C) Details Page 2 VolurnV-olume e !II3,Number 13, Number 177 . Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Friday, Aprilt2, 1993 ~~. Cabrdg,. .... Mascuetacustt .23 0l3. .f... ,_..... .. .... Friday, April 2, 1993 I~~~- _ . ._ | . AEPhi Could Come to MIT City Proposes Parking Changes By Nicole A. Sherry By Aaron Bel:enky eating the parking spaces. The meet- residents and commuters alike, Pre- STAFF REPORTER ADVER SING MANAGER ing was attended by about 25 mem- ston said. Nine undergraduate women hoping to bring a new sorority, Alpha On Tuesday evening, the City of bers of the MIT community, mostly In 1992, the policy was changed Epsilon Phi, to MIT made a presentation to the Panhellenic Associa- Cambridge held a meeting with students with cars who are upset by to allow a limited number of addi- tion Wednesday night. They are awaiting a decision as to whether a MIT students and staff to discuss the current parking situation and tional parking spaces to be allocat- fifth sorority will be invited to come onto campus. drastic changes to on-street parking even more disturbed by the pro- ed. Under the existing plan, for On Wednesday night, the nine women as well as representatives proposed by the city. posed changes. every two unrestricted parking from the national AEPhi organization made a presentation to mem- The meeting focused on the The negative reaction prompted spaces that are converted to some bers of the four existing sororities. -

Nagurski's Debut and Rockne's Lesson

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 20, No. 3 (1998) NAGURSKI’S DEBUT AND ROCKNE’S LESSON Pro Football in 1930 By Bob Carroll For years it was said that George Halas and Dutch Sternaman, the Chicago Bears’ co-owners and co- coaches, always took opposite sides in every minor argument at league meetings but presented a united front whenever anything major was on the table. But, by 1929, their bickering had spread from league politics to how their own team was to be directed. The absence of a united front between its leaders split the team. The result was the worst year in the Bears’ short history -- 4-9-2, underscored by a humiliating 40-6 loss to the crosstown Cardinals. A change was necessary. Neither Halas nor Sternaman was willing to let the other take charge, and so, in the best tradition of Solomon, they resolved their differences by agreeing that neither would coach the team. In effect, they fired themselves, vowing to attend to their front office knitting. A few years later, Sternaman would sell his interest to Halas and leave pro football for good. Halas would go on and on. Halas and Sternaman chose Ralph Jones, the head man at Lake Forest (IL) Academy, as the Bears’ new coach. Jones had faith in the T-formation, the attack mode the Bears had used since they began as the Decatur Staleys. While other pro teams lined up in more modern formations like the single wing, double wing, or Notre Dame box, the Bears under Jones continued to use their basic T. -

Dodgers and Giants Move to the West: Causes and Effects an Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by Nick Tabacca Dr. Tony Edmonds Ball State

Dodgers and Giants Move to the West: Causes and Effects An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) By Nick Tabacca Dr. Tony Edmonds Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2004 May 8, 2004 Abstract The history of baseball in the United States during the twentieth century in many ways mirrors the history of our nation in general. When the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants left New York for California in 1957, it had very interesting repercussions for New York. The vacancy left by these two storied baseball franchises only spurred on the reason why they left. Urban decay and an exodus of middle class baseball fans from the city, along with the increasing popularity of television, were the underlying causes of the Giants' and Dodgers' departure. In the end, especially in the case of Brooklyn, which was very attached to its team, these processes of urban decay and exodus were only sped up when professional baseball was no longer a uniting force in a very diverse area. New York's urban demographic could no longer support three baseball teams, and California was an excellent option for the Dodger and Giant owners. It offered large cities that were hungry for major league baseball, so hungry that they would meet the requirements that Giants' and Dodgers' owners Horace Stoneham and Walter O'Malley had asked for in New York. These included condemnation of land for new stadium sites and some city government subsidization for the Giants in actually building the stadium. Overall, this research shows the very real impact that sports has on its city and the impact a city has on its sports. -

Eagles' Team Travel

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2019-2020 EDITIOn PHILADELPHIA EAGLES Team History The Eagles have been a Philadelphia institution since their beginning in 1933 when a syndicate headed by the late Bert Bell and Lud Wray purchased the former Frankford Yellowjackets franchise for $2,500. In 1941, a unique swap took place between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh that saw the clubs trade home cities with Alexis Thompson becoming the Eagles owner. In 1943, the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh franchises combined for one season due to the manpower shortage created by World War II. The team was called both Phil-Pitt and the Steagles. Greasy Neale of the Eagles and Walt Kiesling of the Steelers were co-coaches and the team finished 5-4-1. Counting the 1943 season, Neale coached the Eagles for 10 seasons and he led them to their first significant successes in the NFL. Paced by such future Pro Football Hall of Fame members as running back Steve Van Buren, center-linebacker Alex Wojciechowicz, end Pete Pihos and beginning in 1949, center-linebacker Chuck Bednarik, the Eagles dominated the league for six seasons. They finished second in the NFL Eastern division in 1944, 1945 and 1946, won the division title in 1947 and then scored successive shutout victories in the 1948 and 1949 championship games. A rash of injuries ended Philadelphia’s era of domination and, by 1958, the Eagles had fallen to last place in their division. That year, however, saw the start of a rebuilding program by a new coach, Buck Shaw, and the addition of quarterback Norm Van Brocklin in a trade with the Los Angeles Rams. -

National Football League Franchise Transactions

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 4 (1982) The following article was originally published in PFRA's 1982 Annual and has long been out of print. Because of numerous requests, we reprint it here. Some small changes in wording have been made to reflect new information discovered since this article's original publication. NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE FRANCHISE TRANSACTIONS By Joe Horrigan The following is a chronological presentation of the franchise transactions of the National Football League from 1920 until 1949. The study begins with the first league organizational meeting held on August 20, 1920 and ends at the January 21, 1949 league meeting. The purpose of the study is to present the date when each N.F.L. franchise was granted, the various transactions that took place during its membership years, and the date at which it was no longer considered a league member. The study is presented in a yearly format with three sections for each year. The sections are: the Franchise and Team lists section, the Transaction Date section, and the Transaction Notes section. The Franchise and Team lists section lists the franchises and teams that were at some point during that year operating as league members. A comparison of the two lists will show that not all N.F.L. franchises fielded N.F.L. teams at all times. The Transaction Dates section provides the appropriate date at which a franchise transaction took place. Only those transactions that can be date-verified will be listed in this section. An asterisk preceding a franchise name in the Franchise list refers the reader to the Transaction Dates section for the appropriate information. -

Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis

Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Before They Were Cardinals SportsandAmerican CultureSeries BruceClayton,Editor Before They Were Cardinals Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Columbia and London Copyright © 2002 by The Curators of the University of Missouri University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201 Printed and bound in the United States of America All rights reserved 54321 0605040302 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cash, Jon David. Before they were cardinals : major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. p. cm.—(Sports and American culture series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8262-1401-0 (alk. paper) 1. Baseball—Missouri—Saint Louis—History—19th century. I. Title: Major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. II. Title. III. Series. GV863.M82 S253 2002 796.357'09778'669034—dc21 2002024568 ⅜ϱ ™ This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984. Designer: Jennifer Cropp Typesetter: Bookcomp, Inc. Printer and binder: Thomson-Shore, Inc. Typeface: Adobe Caslon This book is dedicated to my family and friends who helped to make it a reality This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Prologue: Fall Festival xi Introduction: Take Me Out to the Nineteenth-Century Ball Game 1 Part I The Rise and Fall of Major League Baseball in St. Louis, 1875–1877 1. St. Louis versus Chicago 9 2. “Champions of the West” 26 3. The Collapse of the Original Brown Stockings 38 Part II The Resurrection of Major League Baseball in St. -

Goln' to the DOGS

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 20, No. 6 (1998) GOlN’ TO THE DOGS By Paul M. Bennett They're off and running excitedly and enthusiastically chasing that elusive rabbit. The long since departed and all but forgotten, All-America Football Conference was a professional football league that had "gone to the dogs." Literally! Some football fans, such as those dour National Football League diehards (you know who you are), would say that "going to the dogs" definitely had described the AAFC's level of play during the league's all too brief, four-year tenure as a fiery competitor to the established pro league. Their argument was further reinforced after the league finally called it quits following the end of the 1949 season, when three of its teams (Cleveland Browns, San Francisco 49ers and Baltimore Colts) were absorbed, or merged (if one is kind), into the NFL commencing with the 1950 season. AAFC fans would simply say "pooh" to those NFL naysayers. What did they know? Haughtiness and arrogance seemed to have been their credo. Conservative to a fault. A new idea must be a bad idea! The eight-team AAFC had played football at a level that was both entertaining to the viewing public and similar in quality to that of the older, ten-team league. The only problem the AAFC seemed to have had was its overall lack of depth, talent-wise, and, more importantly, its lack of adequate team competition. The AAFC's chief asset had been the powerful and innovative Cleveland Browns, arguably one of professional football's most dominant franchises. -

Week 5 NFL Preview

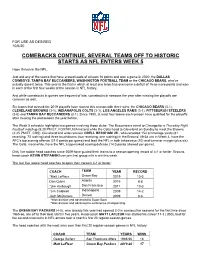

FOR USE AS DESIRED 10/6/20 COMEBACKS CONTINUE, SEVERAL TEAMS OFF TO HISTORIC STARTS AS NFL ENTERS WEEK 5 Hope thrives in the NFL. Just ask any of the teams that have erased leads of at least 16 points and won a game in 2020: the DALLAS COWBOYS, TAMPA BAY BUCCANEERS, WASHINGTON FOOTBALL TEAM or the CHICAGO BEARS, who’ve actually done it twice. This year is the first in which at least one team has overcome a deficit of 16-or-more points and won in each of the first four weeks of the season in NFL history. And while comebacks in games are frequent of late, comebacks in seasons the year after missing the playoffs are common as well. Six teams that missed the 2019 playoffs have started this season with three wins: the CHICAGO BEARS (3-1), CLEVELAND BROWNS (3-1), INDIANAPOLIS COLTS (3-1), LOS ANGELES RAMS (3-1), PITTSBURGH STEELERS (3-0) and TAMPA BAY BUCCANEERS (3-1). Since 1990, at least four teams each season have qualified for the playoffs after missing the postseason the year before. The Week 5 schedule highlights two games involving those clubs. The Buccaneers travel to Chicago for a Thursday Night Football matchup (8:20 PM ET, FOX/NFLN/Amazon) while the Colts head to Cleveland on Sunday to meet the Browns (4:25 PM ET, CBS). Cleveland and wide receiver ODELL BECKHAM JR., who recorded 154 scrimmage yards (81 receiving, 73 rushing) and three touchdowns (two receiving, one rushing) in the Browns' 49-38 win in Week 4, have the AFC’s top scoring offense (31.0 points per game) and lead the NFL in both takeaways (10) and turnover margin (plus six). -

Game Release

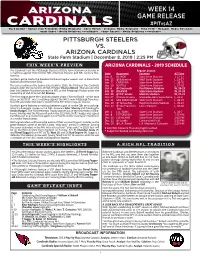

WEEK 14 GAME RELEASE #PITvsAZ Mark Dal ton - Senior Vice Presid ent, Med ia Re l ations Ch ris Mel vin - Director, Med i a Rel ations Mik e He l m - Manag e r, Me d ia Rel ations I mani Sub e r - Me dia R e latio n s Coo rdinato r C hase Russe l l - M e dia Re latio ns Coor dinat or PITTSBURGH STEELERS VS. ARIZONA CARDINALS State Farm Stadium | December 8, 2019 | 2:25 PM THIS WEEK’S PREVIEW ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2019 SCHEDULE The Cardinals host the Pi sburgh Steelers at State Farm Stadium on Sunday in Regular Season a matchup against their former NFL American Division and NFL Century Divi- Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time sion foe. Sep. 8 DETROIT State Farm Stadium T, 27-27 Sunday's game marks the Steelers third-ever regular season visit to State Farm Sep. 15 @ Bal more M&T Bank Stadium L, 23-17 Stadium and fi rst since 2011. Sep. 22 CAROLINA State Farm Stadium L, 38-20 The series between the teams dates back to 1933, the fi rst year the Cardinals Sep. 29 SEATTLE State Farm Stadium L, 27-10 played under the ownership of Hall of Famer Charles Bidwill. That was also the Oct. 6 @ Cincinna Paul Brown Stadium W, 26-23 year the Steelers franchise joined the NFL as the Pi sburgh Pirates under the Oct. 13 ATLANTA State Farm Stadium W, 34-33 ownership of Hall of Famer Art Rooney. Oct. 20 @ N.Y. Giants MetLife Stadium W, 27-21 The fi rst league game the Cardinals played under Charles Bidwill - which took Oct. -

Bert Bell: the Commissioner

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 18, No. 3 (1996) BERT BELL: THE COMMISSIONER Courtesy of The Pro Football Hall of Fame It is not known whether the assembled owners of the National Football League really knew exactly the kind of man they were seeking when, at their January 11, 1946, meeting, they unanimously tapped a fellow owner, Bert Bell of the Pittsburgh Steelers, to replace Elmer Layden as commissioner. But the NFL hierarchy could scarcely catch its collective breath before it became quite clear that they had signed on a fearless, tireless dynamo who would guide the NFL through some of its darkest days into the glamorous Golden Age of the 1950s, when pro football would zoom to new heights of popularity and prosperity. Bell's first order of business as commissioner was to prepare the NFL for "war" with the All-America Football Conference which had been founded in this first post-World war II season armed with apparently plenty of money and a healthy share of the top players of the day. The confrontation was costly to both leagues. Players salaries sky-rocketed. Losses on both sides reached into millions of dollars. In several cities, AAFC and NFL teams vied on common ground for fan support. In Los Angeles for example, the AAFC's Dons outdrew the NFL's Rams in three of the four years of the battle. It soon became obvious that neither side could enjoy any real prosperity while the fighting continued so the AAFC several times made overtures to the older NFL for such things as a common draft, a dovetailing of schedules and an annual "World Series" of pro football between the two league champions. -

2018–19 Susquehanna University Women’S Basketball

2018–19 Susquehanna University Women’s Basketball 2018–19 Susquehanna Women’s Basketball Quick Facts / Table of Contents SUSQUEHANNA UNIVERSITY Front Cover ..................................................................................................................... FC Location ........................... Selinsgrove, Pa. BJ’s Steak and Rib House ............................................................................................... IFC Founded ........................................... 1858 Quick Facts / Table of Contents ........................................................................................ 1 Enrollment ....................................... 2,300 About Susquehanna ......................................................................................................... 2 President .................... Jonathan D. Green Susquehanna Administration ........................................................................................... 3 Head Coach Jim Reed ....................................................................................................... 4 FACTS Assistant Coaches ............................................................................................................. 5 Nickname ..............................River Hawks Meet the River Hawks - Seniors ....................................................................................... 6 Colors .......................... O r a n g e & M a r o o n Meet the River Hawks - Juniors ....................................................................................... -

Market, Financial Analysis, and Economic Impact for Idaho Falls, Idaho Multipurpose Events Center

Final Report Market, Financial Analysis, and Economic Impact for Idaho Falls, Idaho Multipurpose Events Center Idaho Falls, Idaho Prepared for City of Idaho Falls Submitted by Economics Research Associates Spring 2008 Reprinted January 4, 2010 ERA Project No. 17704 10990 Wilshire Boulevard Suite 1500 Los Angeles, CA 90024 310.477.9585 FAX 310.478.1950 www.econres.com Los Angeles San Francisco San Diego Chicago Washington DC New York London Completed Spring 2008 - Reprinted Jan 4, 2010 Table of Contents Section 1. Executive Summary.............................................. 1 Section 2. Introduction and Scope of Services .................... 7 Section 3. Idaho Falls, Idaho Overview ................................ 11 Section 4. Potential Anchor Tenants / Sports Leagues / Other Events ......................................................... 22 Section 5. Comparable Events Centers ................................ 43 Section 6. Events Center – Potential Sizing and Attendance .................................................... 54 Section 7. Financial Analysis – Base Case, High and Low Scenarios ....................................................... 56 Section 8. Economic Impact Analysis ................................... 83 Appendix. Site Analysis Proposed Idaho Falls Multipurpose Events Center ERA Project No. 17704 Page i Completed Spring 2008 - Reprinted Jan 4, 2010 General Limiting Conditions Every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the data contained in this study reflect the most accurate and timely information possible, and they are believed to be reliable. This study is based on estimates, assumptions and other information reviewed and evaluated by Economics Research Associates from its consultations with the client and the client's representatives and within its general knowledge of the industry. No responsibility is assumed for inaccuracies in reporting by the client, the client's agent and representatives or any other data source used in preparing or presenting this study.