One Summer's Paddling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project

Submission to Senate Inquiry: Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project: Potential Impacts on Matters of National Environmental Significance within Modelled Oil Spill Impact Areas (Summer and Winter 2A Model Scenarios) Prepared by Dr David Ellis (BSc Hons PhD; Ecologist, Environmental Consultant and Founder at Stepping Stones Ecological Services) March 27, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 4 Summer Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................. 5 Winter Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................... 7 Threatened Species Conservation Status Summary ........................................... 8 International Migratory Bird Agreements ............................................................. 8 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 Methods .................................................................................................................... 12 Protected Matters Search Tool Database Search and Criteria for Oil-Spill Model Selection ............................................................................................................. 12 Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion of Threatened, Migratory and Marine -

Ceduna 3D Marine Seismic Survey, Great Australian Bight

Referral of proposed action Project title: Ceduna 3D Marine Seismic Survey, Great Australian Bight 1 Summary of proposed action 1.1 Short description BP Exploration (Alpha) Limited (BP) proposes to undertake the Ceduna three-dimensional (3D) marine seismic survey across petroleum exploration permits EPP 37, EPP 38, EPP 39 and EPP 40 located in the Great Australian Bight (GAB). The proposed survey area is located in Commonwealth marine waters of the Ceduna sub-basin, between 1000 m and 3000 m deep, and is about 400 km west of Port Lincoln and 300 km southwest of Ceduna in South Australia. The proposed seismic survey is scheduled to commence no earlier than October 2011 and to conclude no later than end of May 2012. The survey is expected to take approximately six months to complete allowing for typical weather downtime. Outside this time window, metocean conditions become unsuitable for 3D seismic operations. The survey will be conducted by a specialist seismic survey vessel towing a dual seismic source array and 12 streamers, each 8,100 m long. 1.2 Latitude and longitude The proposed survey area is shown in Figure 1 with boundary coordinates provided in Table 1. Table 1. Boundary coordinates for the proposed survey area (GDA94) Point Latitude Longitude 1 35°22'15.815"S 130°48'50.107"E 2 35°11'50.810"S 131°02'16.061"E 3 35°02'37.061"S 131°02'15.972"E 4 35°24'55.520"S 131°30'41.981"E 5 35°14'38.653"S 131°42'16.982"E 6 35°00'47.460"S 131°41'40.052"E 7 34°30'09.196"S 131°02'44.991"E 8 34°06'27.572"S 131°02'11.557"E 9 33°41'24.007"S 130°31'04.931"E 10 33°41'25.575"S 130°15'22.936"E 11 34°08'47.552"S 130°12'34.972"E 12 34°09'16.169"S 129°41'03.591"E 13 34°18'22.970"S 129°29'32.951"E BP Ceduna 3D MSS Referral Page 1 of 48 1.3 Locality and property description The proposed seismic survey will take place in the permit areas for EPP 37, EPP 38, EPP 39 and EPP 40. -

Wilderness Protection Act 1992

Wilderness Protection Act 1992 ANNUAL REPORT 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015 Wilderness Protection Act 1992 Annual Report 2014-15 For further information please contact: Manager, Protected Areas Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources GPO Box 1047 ADELAIDE SA 5001 Telephone: (08) 8124 4707 Website: www.environment.sa.gov.au ABN: 36 702 093 234 ISSN: 1832-9357 IBSN: 978-1-921800-72-6 September 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL ................................................................................... 4 WILDERNESS PROTECTION ACT 1992 ANNUAL REPORT ..................................... 5 OBJECTS OF THE WILDERNESS PROTECTION ACT ............................. 5 ADMINISTRATION OF THE ACT ...................................................... 5 IDENTIFICATION OF LAND UNDER THE ACT ..................................... 5 CONSTITUTION OF LAND UNDER THE ACT ....................................... 6 ANNUAL REPORTING REQUIREMENTS ............................................ 6 NAMES, LOCATIONS AND QUALITY OF WILDERNESS PROTECTION AREAS AND ZONES ................................................................................ 7 EXTENT OF MINING OPERATIONS IN WILDERNESS PROTECTION ZONES14 MANAGEMENT OF WILDERNESS PROTECTION AREAS AND ZONES ...... 14 MANAGEMENT PLANS ADOPTED ................................................... 16 DECLARATION OF PROHIBITED AREAS .......................................... 17 EXPENDITURE ON MANAGEMENT OF WILDERNESS PROTECTION AREAS17 MONIES RECEIVED AND EXPENDED .............................................. -

(Haliaeetus Leucogaster) and the Eastern Osprey (Pandion Cristatus

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 37 - PART 1 - March - 2011 Journal of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. In this issue: Osprey and White-bellied Sea-Eagle populations in South Australia Birds of Para Wirra Recreation Park Bird report 2009 March 2011 1 Distribution and status of White-bellied Sea-Eagle, Haliaeetus leucogaster, and Eastern Osprey, Pandion cristatus, populations in South Australia T. E. DENNIS, S. A. DETmAR, A. V. BROOkS AND H. m. DENNIS. Abstract Surveys throughout coastal regions and in the INTRODUCTION Riverland of South Australia over three breeding seasons between May 2008 and October 2010, Top-order predators, such as the White-bellied estimated the population of White-bellied Sea- Sea-Eagle, Haliaeetus leucogaster, and Eastern Eagle, Haliaeetus leucogaster, as 70 to 80 pairs Osprey, Pandion cristatus, are recognised and Eastern Osprey, Pandion cristatus, as 55 to indicator species by which to measure 65 pairs. Compared to former surveys these data wilderness quality and environmental integrity suggest a 21.7% decline in the White-bellied Sea- in a rapidly changing world (Newton 1979). In Eagle population and an 18.3% decline for Eastern South Australia (SA) both species have small Osprey over former mainland habitats. Most (79.2%) populations with evidence of recent declines sea-eagle territories were based on offshore islands linked to increasing human activity in coastal including Kangaroo Island, while most (60.3%) areas (Dennis 2004; Dennis et al. 2011 in press). osprey territories were on the mainland and near- A survey of the sea-eagle population in the shore islets or reefs. The majority of territories were mid 1990s found evidence for a decline in the in the west of the State and on Kangaroo Island, with breeding range since European colonisation three sub-regions identified as retaining significant (Dennis and Lashmar 1996). -

080058-89.02.017.Pdf

t9l .Ig6I pup spu?Fr rr"rl?r1mv qnos raq1oaqt dq panqs tou pus 916I uao^\teq sluauennboJ puu surelqord lusue8suuur 1eneds wq sauo8a uc .fu1mpw snorru,r aql uI luar&(oldua ',uq .(tg6l a;oJareqt puuls1oore8ueltr 0t dpo 1u reted lS sr ur saiuzqc aql s,roqs osIB elqeJ srqt usrmoJ 'urpilsny 'V'S) puels tseSrul geu oq; ur 1sa?re1p4ql aql 3o luetugedeq Z alq?J rrr rtr\oqs su padoldua puu prr"lsr aroqsJJorrprJpnsnv qlnos lsJErel aql ruJ ere,u eldoed ZS9 I feqf pa roqs snsseC srllsll?ls dq r ?olp sp qlr^\ puplsl oorp8ue1 Jo neomg u"rl?Jlsnv eql uo{ sorn8g luereJ lsour ,u1 0g€ t Jo eW T86I ul puu 00S € ,{lel?urxorddu sr uoqelndod '(derd ur '8ur,no:8 7r luosaJd eqJ petec pue uoqcnpord ,a uosurqoU) uoqecrJqndro3 peredard Smeq ,{11uermc '(tg6l )potsa^q roJ perualo Suraq puel$ oql Jo qJnu eru sda,r-rnsaseql3o EFSer pa[elop aqJ &usJ qlvrr pedolaaap fuouoce Surqsg puu Surure; e puu pue uosurqo;) pegoder useq aleq pesn spoporu palles-er su,rr prrqsr eql sreo,{ Eurpeet:ns eq1 re,ro prru s{nser druuruqord aqt pue (puep1 ooreSuqtr rnq 698I uI peuopwqs sE^\ elrs lrrrod seaeell eql SumnJcxa) sprrelsl aroqsJJo u"{e4snv qlnos '998I raqueJeo IIl eprelepv Jo tuaruslDesIeuroJ oqt aql Jo lsou uo palelduor ueeq A\ou aaeq s,{e,rrns aro3aq ,(ueduo3 rr"4u4snv qtnos qtgf 'oAE eqt dq ,{nt p:6o1org sree,{009 6 ol 000 L uea r1aq palulosr ur slors8rry1 u,no1paserd 6rll J?eu salaed 'o?e ;o lrrrod ererrirspuulsr Surura sr 3ql Jo dllJolpu aq; sree,{ paqslqplse peuuurad lE s?a\lueurep1os uuedorng y 009 0I spuplsl dpearg pue uosr"ed pup o8e srea,{ 'seruolocuorJ-"3s rel?l puB -

S P E N C E R G U L F S T G U L F V I N C E N T Adelaide

Yatala Harbour Paratoo Hill Turkey 1640 Sunset Hill Pekina Hill Mt Grainger Nackara Hill 1296 Katunga Booleroo "Avonlea" 2297 Depot Hill Creek 2133 Wilcherry Hill 975 Roopena 1844 Grampus Hill Anabama East Hut 1001 Dawson 1182 660 Mt Remarkable SOUTH Mount 2169 440 660 (salt) Mt Robert Grainger Scobie Hill "Mazar" vermin 3160 2264 "Manunda" Wirrigenda Hill Weednanna Hill Mt Whyalla Melrose Black Rock Goldfield 827 "Buckleboo" 893 729 Mambray Creek 2133 "Wyoming" salt (2658±) RANGE Pekina Wheal Bassett Mine 1001 765 Station Hill Creek Manunda 1073 proof 1477 Cooyerdoo Hill Maurice Hill 2566 Morowie Hill Nackara (abandoned) "Bulyninnie" "Oak Park" "Kimberley" "Wilcherry" LAKE "Budgeree" fence GILLES Booleroo Oratan Rock 417 Yeltanna Hill Centre Oodla "Hill Grange" Plain 1431 "Gilles Downs" Wirra Hillgrange 1073 B pipeline "Wattle Grove" O Tcharkuldu Hill T Fullerville "Tiverton 942 E HWY Outstation" N Backy Pt "Old Manunda" 276 E pumping station L substation Tregalana Baroota Yatina L Fitzgerald Bay A Middleback Murray Town 2097 water Ucolta "Pitcairn" E Buckleboo 1306 G 315 water AN Wild Dog Hill salt Tarcowie R Iron Peak "Terrananya" Cunyarie Moseley Nobs "Middleback" 1900 works (1900±) 1234 "Lilydale" H False Bay substation Yaninee I Stoney Hill O L PETERBOROUGH "Blue Hills" LC L HWY Point Lowly PEKINA A 378 S Iron Prince Mine Black Pt Lancelot RANGE (2294±) 1228 PU 499 Corrobinnie Hill 965 Iron Baron "Oakvale" Wudinna Hill 689 Cortlinye "Kimboo" Iron Baron Waite Hill "Loch Lilly" 857 "Pualco" pipeline Mt Nadjuri 499 Pinbong 1244 Iron -

Maintaining the Monitoring of Pup Production at Key Australian Sea Lion Colonies in South Australia (2013/14)

Maintaining the monitoring of pup production at key Australian sea lion colonies in South Australia (2013/14) Simon D Goldsworthy, Alice I Mackay, Peter D Shaughnessy, Fred Bailleul and Clive R McMahon SARDI Publication No. F2010/000665-4 SARDI Research Report Series No. 818 SARDI Aquatics Sciences PO Box 120 Henley Beach SA 5022 December 2014 Final report to the Australian Marine Mammal Centre Goldsworthy, S.D. et al. Australian sea lion population monitoring Maintaining the monitoring of pup production at key Australian sea lion colonies in South Australia (2013/14) Final report to the Australian Marine Mammal Centre Simon D Goldsworthy, Alice I Mackay, Peter D Shaughnessy, Fred Bailleul and Clive R McMahon SARDI Publication No. F2010/000665-4 SARDI Research Report Series No. 818 December 2014 II Goldsworthy, S.D. et al. Australian sea lion population monitoring This publication may be cited as: Goldsworthy, S.D.1, Mackay, A.I.1, Shaughnessy, P.D. 1, 2, Bailleul, F1 and McMahon, C.R.3 (2014). Maintaining the monitoring of pup production at key Australian sea lion colonies in South Australia (2013/14). Final Report to the Australian Marine Mammal Centre. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2010/000665-4. SARDI Research Report Series No. 818. 66pp. Cover Photo: Alice I. Mackay 1 SARDI Aquatic Sciences, PO Box 120, Henley Beach, SA 5022 2South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA, 5000 3 Sydney Institute of Marine Science, 19 Chowder Bay Road, Mosman NSW, 2088 South Australian Research and Development Institute SARDI Aquatic Sciences 2 Hamra Avenue West Beach SA 5024 Telephone: (08) 8207 5400 Facsimile: (08) 8207 5406 http://www.sardi.sa.gov.au DISCLAIMER The authors warrant that they have taken all reasonable care in producing this report. -

Name of Applicant Rokrol Pty Ltd C/- Future Urban Group Proposal

Development Assessment Commission AGENDA ITEM 2.2.2 22 June 2017 Name of Applicant Rokrol Pty Ltd c/- Future Urban Group Proposal Tourist Accommodation Address Section 390, Cape St Albans – Kangaroo Island DA Number: 520/L001/17 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO AGENDA REPORT 2- 34 Appendix 1: Development Plan Provisions ATTACHMENTS 1: APPLICATION & PLANS 35 – 111 2: PHOTOS 112 – 113 3: AGENCY COMMENTS 114 – 129 4: COUNCIL COMMENTS or TECHNICAL ADVICE 130 5: ADDITIONAL INFORMATION – Applicants Response to 131 - 134 Coast Protection Board Comments 1 Development Assessment Commission AGENDA ITEM 2.2.2 22 June 2017 OVERVIEW Application No 520/L001/17 Unique ID/KNET ID Edala Id: 1779 / Knet File: 2017/03956/01 Applicant Rockrol Pty Ltd c/- Future Urban Group Proposal Tourist Accommodation Subject Land Section 309, Hd of Dudley, Cape St. Albans (Red House Bay) Zone/Policy Area Coastal Conservation Relevant Authority Development Assessment Commission: Schedule 10 (18) – Tourism development within the Coastal Conservation Zone, Kangaroo Island. Lodgement Date 23 January 2017 Council Kangaroo Island Development Plan Consolidated 17 September 2015 Type of Development Merit Public Notification Category 2 Representations None Referral Agencies Coast Protection Board Kangaroo Island Natural Resources (DEWNR) Report Author Lee Webb, Senior Specialist (Environmental) Planner RECOMMENDATION Development Plan Consent subject to reserved matters and conditions EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The proposal is to establish an ecotourism style of tourist accommodation development on a coastal rural allotment at Cape St Albans (Red House Bay) on the north-eastern coast of Dudley Peninsula - Kangaroo Island, approximately 20 kilometres north-east of Penneshaw. The proposal is in accordance with the Islands strategic direction to promote the nature-based tourism industry as a key economic driver. -

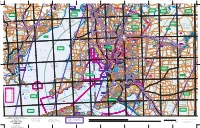

South Australian Coastal Viewscapes Project 81 5. MAPPING COASTAL

81 South Australian Coastal Viewscapes Project 5. MAPPING COASTAL SCENIC • The insights provided by the predictive QUALITY models (Section 4.11) • Oblique aerial photographs covering 5.1 DERIVATION OF THE MAP most of the South Australian coast available on-line from the Atlas of South Requirements Australia (www.atlas.sa.gov.au) • Maps covering the entire coast at The Project Brief specified that the scenic 1:100,000 scale showing the coastal value of the coast was to be mapped at a viewshed. In addition, 1:50,000 scale scale sufficient for planning and policy viewshed maps were produced of the development. It specified that it would not major bays on Eyre Peninsula – e.g. generally extend beyond one kilometre inland Venus Bay, Baird Bay. from the sea. It would also cover offshore areas to the extent that scenic amenity might Scenic Quality Rating be influenced by marina development. It covered areas subject to tidal influence to The scenic quality rating numbers such as a supra tidal levels, and also river estuaries. figure of 5 covered the range from 5.00 to Information on the regions was to be provided 5.99. It could be a high 5 (e.g. 5.8), middle 5 in the following order of priority: (e.g. 5.5) or a low 5 (e.g. 5.2). The number did not differentiate within the integer and thus • Eyre Peninsula (border to Port Augusta) provided a reasonably robust figure capable of • Kangaroo Island covering the variations within a scene and the • South East (border to Murray Mouth) concomitant changes in scenic quality. -

Great Southern Land: the Maritime Exploration of Terra Australis

GREAT SOUTHERN The Maritime Exploration of Terra Australis LAND Michael Pearson the australian government department of the environment and heritage, 2005 On the cover photo: Port Campbell, Vic. map: detail, Chart of Tasman’s photograph by John Baker discoveries in Tasmania. Department of the Environment From ‘Original Chart of the and Heritage Discovery of Tasmania’ by Isaac Gilsemans, Plate 97, volume 4, The anchors are from the from ‘Monumenta cartographica: Reproductions of unique and wreck of the ‘Marie Gabrielle’, rare maps, plans and views in a French built three-masted the actual size of the originals: barque of 250 tons built in accompanied by cartographical Nantes in 1864. She was monographs edited by Frederick driven ashore during a Casper Wieder, published y gale, on Wreck Beach near Martinus Nijhoff, the Hague, Moonlight Head on the 1925-1933. Victorian Coast at 1.00 am on National Library of Australia the morning of 25 November 1869, while carrying a cargo of tea from Foochow in China to Melbourne. © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available from the Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Assistant Secretary Heritage Assessment Branch Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment and Heritage. -

A Preliminary Survey of the Western Blue Groper on Kangaroo Island

A PRELIMINARY SURVEY OF THE WESTERN BLUE GROPER ON KANGAROO ISLAND By Scoresby A. Shepherd, James Brook and Adrian Brown Reefwatch, c/o Conservation Council of South Australia, 120 Wakefield St, Adelaide, 5000. 30 June 2002 Photo: Adrian Brown A PRELIMINARY SURVEY OF THE WESTERN BLUE GROPER ON KANGAROO ISLAND By Scoresby A. Shepherd1, James Brook2 and Adrian Brown3 1Senior Research Fellow, South Australian Research and Development Institute 2PO Box 111, Normanville, SA, 5204. 3 9 Duffield St, Gawler East 5118. SUMMARY The abundance of the western blue groper (WBG), Achoerodus gouldii, was examined in the nearshore rocky reef areas on the western and northern coasts of Kangaroo Island, which is near the eastern limit of the species’ geographic range. Adult males occupied a home range which at several sites was estimated to vary from 4 000 to 16 000 m2. Females and sub-adults are site-attached and swim in loose aggregations. The use of transect lines of 100 m with which a diver sampled an area of 500 m2 of the substratum with 5-8 replicates was found to be an appropriate sampling strategy to estimate abundance of sub-adult blue groper 20-60 cm size with adequate precision, but not enough for the less abundant juveniles and adults. Densities of juveniles (<20 cm size) ranged from 0.1 to 0.4 per 500 m2 at most sites but were a hundred times higher in a shallow sheltered site at Penneshaw. Sub-adult densities ranged from zero to 5.7 per 500 m2 and tended to decrease with increasing distance from the western end of the island.