Nationalist Historians on Sikh History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download/Pdf/144517771.Pdf 14

i CONTENTS l.fjswg Who Killed Guru Tegh Bahadur? 1 Sirdar Kapur Singh, ICS Understanding The Sacrifice of Guru Tegh Bahadar Ji 14 Dr. Kehar Singh sRI gurU qyg bhwdr bwxI dw dwrSnk p`K 19 fw. jgbIr isµG Guru Tegh Bahadur’s Bani- Conceptual Analysis 26 Dr. Gurnam Kaur Relevance of Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji For Today’s Indian Plural Society 39 Dr. Mohd. Habib Teachings of Sri Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji: A Perspective 48 Dr. D. P. Singh Travels of Guru Tegh Bahadur 70 Dr. Harpreet Kaur The Making of A Martyr: Guru Tegh Bahadur And His Times 84 Sr. Rupinder Singh Brar gurU qyg bhwdr jI dI bwxI iv`c mn dI pySkwrI 102 fw. AmrdIp kOr, SrndIp kOr ii Guru Tegh Bahadur Dev Ji: An Apostle Of Human Rights And Supreme Sacrifice 111 Dr. Sughandh Kohli Kaang Book Review By Dr. Bhai Harbans Lal 117 By Dr. Hardev Singh Virk 125 Contributors 130 Our Publications 131 ac iii sMpwdkI sw DrqI BeI hirAwvlI ijQY myrw siqguru bYTw Awie ] sw jMq Bey hirAwvly ijnI myrw siqguru dyiKAw jwie ] sMn 2020 SqwbdIAW dw vrHw irhw [ BwvyN smu`cw ivSv ies smyN kronw vrgI mhWmwrI dw swhmxw kr irhw hY pr gurU bKiSS sdkw ies kwl dOrwn vI gurU swihb duAwrw vrosweIAW pMQk sMsQwvW mnu`Kqw dI syvw iv`c hwjr hoeIAW hn Aqy dySW-ivdySW iv`c is`K pMQ dI Swn au~cI hoeI hY [ gurU swihb dy kysrI inSwn swihb ƒ ivdySW dI DrqI 'qy JulwieAw igAw hY [ ies smyN sRI gurU nwnk dyv jI, sRI gurU qyg bhwdr swihb jI, Bgq nwmdyv jI, bwbw bMdw isMG bhwdr jI Aqy is`K pMQ dI isrmor sMsQw SRomxI gurduAwrw pRbMDk kmytI, sRI AMimRqsr nwl sMbMiDq SqwbdIAW pUry ivSv dI sMgqW duAwrw ijQy prMprwgq rUp iv`c mnweIAW geIAW -

Alameda County Board of Education

ALAMEDA COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION AGENDA FOR THE REGULAR MEETING, VOL. XXVII, NO. 02 Regular Board Meeting, August 14, 2012 – 3:00 p.m. MEETING LOCATION: Alameda County Office of Education 313 W Winton Avenue Hayward, CA 94544 510-887-0152 www.acoe.org CALL TO ORDER: Time: P.M. SALUTE TO THE FLAG ROLL CALL: President Cerrato _____ Vice-President Rivera _____ Trustee Berrick _____ Trustee Knowles _____ Trustee McDonald _____ Trustee McWilson _____ Trustee Sims _____ Any member of the public may comment on agenda items, as each item is presented. Individuals wishing to address the Board need to complete a Speaker Card located at the entrance to the meeting room and provide it to the recording secretary prior to the start of the meeting. Speakers are asked to limit their comments to two minutes each, and the Board president may limit the amount of discussion time for any one agenda item. For non-agenda items, there is a separate opportunity for comments during the Items from the Floor portion of the agenda. By law, board members may not enter into discussion nor take action on any item not previously published on the agenda. Mission Statement: Provide, promote and support leadership and service to ensure the success of Every Child…in Every School…Every Day! 1. Interdistrict Transfer The Board will hear and take action on the INFORMATION/ Appeal interdistrict transfer appeal IDT # 06-DR- ACTION IDT # 06-DR-12/13 12/13 from San Leandro Unified School District (USD) to Berkeley USD. This matter will be heard in closed session. -

The Jails and the Women Prisoners As They Exist……

CHAPTER - 1 THE JAILS AND THE WOMEN PRISONERS AS THEY EXIST……. The state of Punjab is a prosperous region known for its industrious and hardworking people. But even as these tall well built people cope with numerous specific regional problems, accept changes and grow in a global world – the glaring fact that needs specific attention, is the growing incidence of crime and even more so - the growing incidence of crime committed by women. The changing nature and patterns of these crimes require serious consideration. Most jails had little or no provisions for women to start with - later some arrangements were made to accommodate them. With the increase in women prisoners in each jail the area of confinement is deficient in many ways. Taking up the region of Punjab, which is the focus of the present study, we find that all the prisons located in the various parts of Punjab do not have provisions to keep women prisoners. Only the District and Central jails, which are eight in number, have some provisions to keep women prisoners. There is one exclusive jail for women at Ludhiana, which houses only women prisoners. Once convicted, the women from all the other eight jails are supposed to be sent to this jail. However, a large number of under- trails are also lodged here. Women are under detention in the dowry act cases, drug trafficking- NDPS act, excise act, theft, murders due to family disputes and illicit relationships. A majority of the women prisoners belong to the lower socio-economic strata, a few to the lower middle class and a very few belong to the middle middle class strata of society. -

Banda Bahadur

=0) |0 Sohan Singh Banda the Brave ^t:- ;^^^^tr^ y^-'^;?^ -g^S?^ All rights reserved. 1 € 7?^ ^jfiiai-g # oft «3<3 % mm "C BANDA THE BRAVE BY 8HAI SOHAN SINfiH SHER-I-BABAE. Published by Bhai NARAiN SINGH Gyani, Makaqeb, The Puiyabi Novelist Co,, MUZAm, LAHORE. 1915. \^t Edition?^ 1000 Copies. [Pmy 7 Hupef. 1 § J^ ?'Rl3]f tft oft ^30 II BANDA THE BRAVE OR The Life and Exploits OF BANDA BAHADUB Bliai SoJiaii Siiigli Shei-i-Babar of Ciiijrainvala, Secretarv, Office of the Siiperiiitendeiit, FARIDKOT STATE. Fofiuerly Editor, the Sikhs and Sikhism, and ' the Khalsa Advocate ; Author of A Tale of Woe/ *Parem Soma/ &c., &c. PXJ]E>irjrABX I^O^irElL,IST CO., MUZANG, LAHORE. Ut Edition, Price 1 Rupee. PRINTED AT THE EMPIRE PRESS, LAHORE. — V y U L — :o: My beloved Saviour, Sri Guru Gobind Singh Ji Kalgi Dhar Maharaj I You sacrificed your loving father and four darlings and saved us, the ungrateful people. As the subject of this little book is but a part and parcel of the great immortal work that you did, and relates to the brilliant exploits and achievements of your de- voted Sikhs, I dedicate it to your holy name, in token of the deepest debt of gratitude you have placed me and mine under, in the fervent hope that it may be of some service to your beloved Panth. SOHAN SINGH. FREFAOE. In my case, it is ray own family traditions that actuated me to take up my pen to write this piece of Sikh History. Sikhism in my family began with my great great grand father, Bhai Mansa Singh of Khcm Karn, Avho having received Amrita joined the Budha Dal, and afterwards accompanied Sardar Charat Singh to Giijranwala. -

Reading Writing Spoken Language Transcript Maths Science Forces

Reading Maths Science Apply knowledge of root words, prefixes and suffixes to read aloud and to Match 2-place decimals to 1/100s, using a place value grid Forces understand the meaning of unfamiliar words. Use place value to multiply and divide numbers by 10 and 100, involving 2- Read further exception words, noting the unusual correspondences between place decimals Investigation spelling and sound, and where these occur in the word. Use place value to add and subtract 0·1 and 0·01 to and from decimal Explore different ways to test an idea, choose the best way, and Become familiar with and talk about a wide range of books, including myths, numbers legends and traditional stories and books from other cultures and traditions give reasons and know their features. Use doubling and halving to multiply and divide by 4 and 8 and solve Vary one factor whilst keeping the others the same in an Read non-fiction texts and identify purpose and structures and grammatical correspondence problems experiment features and evaluate how effective they are. Use advanced mental multiplication strategies Explain why they do this Use meaning-seeking strategies to explore the meaning of words in context Add/subtract 2-digit numbers to/from 2-digit numbers by counting on/bar Plan and carry out an investigation by controlling variables fairly Add pairs of 2-digit numbers with a total ≤ 198 and accurately Writing Subtract 2-digit from 2-digit numbers by counting up Make a prediction with reasons Use number facts to 10 to solve problems including word problems Use -

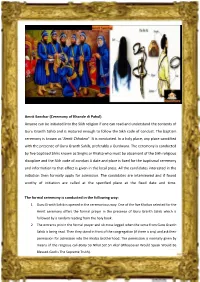

Amrit Sanskar) Should Be Held at an Exclusive Place Away from Common Human Traffic

Amrit Sanchar (Ceremony of Khande di Pahul) Anyone can be initiated into the Sikh religion if one can read and understand the contents of Guru Granth Sahib and is matured enough to follow the Sikh code of conduct. The baptism ceremony is known as 'Amrit Chhakna". It is conducted. In a holy place, any place sanctified with the presence of Guru Granth Sahib, preferably a Gurdwara. The ceremony is conducted by five baptized Sikhs known as Singhs or Khalsa who must be observant of the Sikh religious discipline and the Sikh code of conduct A date and place is fixed for the baptismal ceremony and information to that effect is given in the local press. All the candidates interested in the initiation then formally apply for admission. The candidates are interviewed and if found worthy of initiation are called at the specified place at the fixed date and time. The formal ceremony is conducted in the following way: 1 Guru Granth Sahib is opened in the ceremonious way. One of the five Khalsas selected for the Amrit ceremony offers the formal prayer in the presence of Guru Granth Sahib which is followed by a random reading from the holy book. 2 The entrants join in the formal prayer and sit cross legged when the verse from Guru Granth Sahib is being read. Then they stand in front of the congregation (if there is any) and ask their permission for admission into the Khalsa brotherhood. The permission is normally given by means of the religious call-Bolay So Nihal Sat Sri Akal (Whosoever Would Speak Would Be Blessed-God Is The Supreme Truth). -

A Man Called Banda © 2019 Rupinder Singh Brar, Yuba City, CA

A Man Called Banda © 2019 Rupinder Singh Brar, Yuba City, CA. All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval process, without permission in writing from the publisher. -- Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brar, Rupinder S. 1961-, author A Man Called Banda / by Rupinder S. Brar ; 2019. | Includes bibliographical references. pages ; cm Front cover: A silhouette of a statue of Banda Bahadur from a monument to him at Chappar Chiri, Punjab, India 8 A MAN CALLED BANDA Rupinder Singh Brar 10 Table of Contents The Prophet and the Ascetic 6 The Road to Chappar Chiri 15 Provisions Arms and Victory 20 The Guru Will Protect You 28 Two and a Half Strikes 34 Defeat Defiance and Redemption 40 Life and Death in the Garden of Good and Evil 47 The Age of the Mughals 50 The House of Nanak and the House of Babur 58 The Empire in Crisis 65 The Khalsa Revolution 72 Just War: 77 A Moral Case for Rebellion 77 Assessing a Legend: 85 The Ethics of Banda’s War 85 Bandhi Bir 94 12 PART I COMES A WARRIOR BRAVE Chapter 1 The Prophet and the Ascetic Meticulously maintained weather charts at NASA confirm that on September 14th, 1708, a solar eclipse was witnessed in the northern hemisphere that included almost all parts of India. On that day, many historians believe, an unknown ascetic named Madho Das became a disciple of Guru Gobind Singh and came to be known as Banda. -

Baby Naming Ceremony – Naam Karan

Baby Naming Ceremony – Naam Karan Cut out the statements, read through them and see if you can arrange them in the correct order. Research ‘baby naming ceremony in Sikhism’ using the Internet to see if you were correct. When a woman first discovers she When the baby is born, the mool is pregnant, she will recite prayers If this is their first child, the parents mantra (the fundamental belief of thanking Waheguru for the gift of the may refer to the Sikh Rahit Maryada Sikhism) is whispered into the baby’s child. She will ask Waheguru for the (code of conduct) to check what the ear. A drop of honey is also placed in protection and safety of the foetus procedure is for the naam karan. the baby’s mouth. as it develops. The family brings a gift to the Gurd- Both parents (as soon as the moth- wara. It may be a rumalla (piece of er is able to), along with any family The granthi opens the Guru Granth cloth used to cover the Guru Granth member who wishes to join in on Sahib at random and reads the pas- Sahib), some food to be used in the the naam karan, will go to their local sage on that page to the sangat (con- langar or a monetary donation to Gurdwara within 40 days of the ba- gregation). put in the donation box by the manji by’s birth. granth. Once the parents have chosen the Karah Prashad (a sweet semolina The parents choose a name using baby’s first name, the granthi will mix) is then distributed to everyone, the first letter of the first word from then give the child the surname Kaur, shared out from the same bowl. -

Sikhism Reinterpreted: the Creation of Sikh Identity

Lake Forest College Lake Forest College Publications Senior Theses Student Publications 4-16-2014 Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity Brittany Fay Puller Lake Forest College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://publications.lakeforest.edu/seniortheses Part of the Asian History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Puller, Brittany Fay, "Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity" (2014). Senior Theses. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Lake Forest College Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Lake Forest College Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity Abstract The iS kh identity has been misinterpreted and redefined amidst the contemporary political inclinations of elitist Sikh organizations and the British census, which caused the revival and alteration of Sikh history. This thesis serves as a historical timeline of Punjab’s religious transitions, first identifying Sikhism’s emergence and pluralism among Bhakti Hinduism and Chishti Sufism, then analyzing the effects of Sikhism’s conduct codes in favor of militancy following the human Guruship’s termination, and finally recognizing the identity-driven politics of colonialism that led to the partition of Punjabi land and identity in 1947. Contemporary practices of ritualism within Hinduism, Chishti Sufism, and Sikhism were also explored through research at the Golden Temple, Gurudwara Tapiana Sahib Bhagat Namdevji, and Haider Shaikh dargah, which were found to share identical features of Punjabi religious worship tradition that dated back to their origins. -

You Are Here the Journal of Creative Geography

you are here the journal of creative geography THE BORDERLANDS ISSUE Exploring borders in the land, real, imagined and remembered { poetry, fiction & creative non-fiction } 2009 www.u.arizona.edu/urhere~ $10 © 2009 you are here, Department of Geography at the University of Arizona. you are here is made possible by grants, donations and subscriptions. We would like to thank all of our readers and supporters, as well as the following institutions at the University of Arizona for their sponsorship: College of Social and Behavioral Sciences Department of Anthropology Department of Geography & Regional Development Graduate College Office of the Vice President for Research, Graduate Studies, and Economic Development Southwest Center Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy Editor: Rafael Routson Cover art: Ben Kirkby. Art Direction/Design: Margaret Kimball Opposite page (photograph by Jay Dusard): “Even on the clearest of days you can’t see the Weavers from de Chelly. They are about 230 miles apart, as the condor flies. Astronauts can see them both at the same time, but the angle of view is radically different. This geographic impossibility was created in the darkroom using two negatives, two enlargers, careful registration, and precision bleaching in the narrow ‘blend zone’ between the component images.” This was published in the Spring issue of Living Cowboy Ethics: The Journal of the Paragon Foundation. you are here the journal of creative geography 2009 Weaver Mountains from Canyon de Chelly: A Geographic Impossibility, jay dusard, black and white photograph. founded in 1998 University of Arizona • Department of Geography OUR STAFF editor Rafael Routson art director Margaret Kimball assistant editor/intern Jenny Gubernick editorial review committee Audra El Vilaly Jamie Mcevoy Evan Dick Tom Keasling Georgia Conover Ian Shaw Lawrence Hoffman Jesse Minor Geoff Boyce Jessica de la Ossa Ashley Coles Jen Rice Susan Kaleita faculty advisors Sallie Marston Ellen McMahon administrative assistance Linda E. -

SELF IDENTITY and BRITISH PERCEPTION of SIKH SOLDIERS Ravneet Kaur Assistant Professor University School of Legal Studies (UILS) Panjab University, Chandigarh

© 2021 JETIR May 2021, Volume 8, Issue 5 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) SELF IDENTITY AND BRITISH PERCEPTION OF SIKH SOLDIERS Ravneet Kaur Assistant Professor University School of Legal Studies (UILS) Panjab University, Chandigarh. Abstract This paper is oriented towards identifying the various elements that went into the formation of the self perception of the Sikh soldiers. The origins of the Martial Race theory, that was used very effectively and innovatively by the British to mobilise the Sikhs and induct them into the most vital and visible echelons of the British Indian army, will be traced. The socio-religious and economic implications that made the Sikhs readily accept and perpetuate the martial race considerations will be explored. The hard pragmatism, realistic evaluation and real-political considerations that intertwined to lend credence and support to the perception of the Sikhs as the premier martial community of India in not only the Army top brass and officers, but also British decision making and opinion forming class and institutions in Britain will be dwelled upon. The chapter will look into the self perception of Sikhs and the various ways in which they were viewed by the British, both as a community and as soldiers. Keywords- Sikh, British, Soldiers, Perception, Martial Race Theory Ashis Nandy in his book ‘The Intimate enemy’1 puts forward the contention that colonial cultures bind the ruler and the ruled into an ‘unbreakable dyadic relationship’. Many Indians unconsciously identified their salvation in emulating the British – in friendship and in enmity. They may have not shared the British idea of Martial races- the hyper masculine, manifestly courageous, superbly loyal Indians castes and subcultures mirroring the British middle class sexual stereotypes- but they did resurrect the ideology of the martial races latent in the traditional Indian concept of statecraft and gave the idea a new centrality. -

1 Do Not Reproduce This Article in Part Or Full Without Written Permission of Author How the British Divided Punjab Into Hindu

How the British divided Punjab into Hindu and Sikh By Sanjeev Nayyar December 2016 This is chapter 2 from the E book on Khalistan Movement published by www.swarajyamag.com During a 2012 visit to Naina Devi Temple in Himachal Pradesh, about an hour's drive from Anandpur Sahib, I wondered why so many Sikhs come to the temple for darshan. The answer lies in the events of 1699. In the Chandi Charitra, the tenth Guru says that in the past god had deputed Goddess Durga to destroy evil doers. That duty was now assigned to him hence he wanted her blessings. So he invited Pandit Kesho from Kashi to conduct the ceremony at the hill of Naina Devi. The ceremony started on Durga Ashtami day, in the autumn of October 1698, and lasted for six months. At the end of this period, the sacred spring Navratras began on 21 March 1699. Then, “When all the ghee and incense had been burnt and the goddess had yet not appeared, the Guru came forward with a naked sword and, flashing it before the assembly declared: ‘This is the goddess of power!” This took place on 28 March 1699, the Durga Ashtami day. The congregation was then asked to move to Anandpur, where on New Year Day of 1st Baisakh, 1699, the Guru would create a new nation.” 3 On 30 March 1699, at Anandpur, Govind Singhji gave a stirring speech to the assembly about the need to protect their spiritual and temporal rights. He then asked if anyone would offer his head in the services of God, Truth and Religion.