Love's Final Irony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Screwball Syll

Webster University FLST 3160: Topics in Film Studies: Screwball Comedy Instructor: Dr. Diane Carson, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course focuses on classic screwball comedies from the 1930s and 40s. Films studied include It Happened One Night, Bringing Up Baby, The Awful Truth, and The Lady Eve. Thematic as well as technical elements will be analyzed. Actors include Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, Clark Gable, and Barbara Stanwyck. Class involves lectures, discussions, written analysis, and in-class screenings. COURSE OBJECTIVES: The purpose of this course is to analyze and inform students about the screwball comedy genre. By the end of the semester, students should have: 1. An understanding of the basic elements of screwball comedies including important elements expressed cinematically in illustrative selections from noteworthy screwball comedy directors. 2. An ability to analyze music and sound, editing (montage), performance, camera movement and angle, composition (mise-en-scene), screenwriting and directing and to understand how these technical elements contribute to the screwball comedy film under scrutiny. 3. An ability to apply various approaches to comic film analysis, including consideration of aesthetic elements, sociocultural critiques, and psychoanalytic methodology. 4. An understanding of diverse directorial styles and the effect upon the viewer. 5. An ability to analyze different kinds of screwball comedies from the earliest example in 1934 through the genre’s development into the early 40s. 6. Acquaintance with several classic screwball comedies and what makes them unique. 7. An ability to think critically about responses to the screwball comedy genre and to have insight into the films under scrutiny. -

GAILY, GAILY the NIGHT THEY RAIDED MINSKY's “In 1925, There

The one area where it succeeded perfectly was So, Rosenblum began refashioning the film, in its score by Henry Mancini. By this time, using a clever device of stock footage that Mancini was already a legend. After toiling in the would lead into the production footage, rear - GAILY, GAILY music department at Universal (the highlight of ranging and restructuring scenes, and spend - his tenure there would be Orson Welles’ Touch ing a year doing so – the result was stylish and Of Evil) , he hit it big, first with his TV score to visually interesting and it transformed the film THE NIGHT Peter Gunn – which not only provided that from disaster into a hit. THEY RAIDED MINSKY’S Blake Edwards series with its signature sound, but which also produced a best-selling album The score for Minsky’s was written by Charles on RCA – and then in a series of films for which Strouse, who’d already written several Broad - “In 1925, he provided amazing scores, one right after an - way shows, as well as the score for the film other – Breakfast At Tiffany’s, Charade, Hatari, Bonnie and Clyde . The lyrics were by Lee there was this real The Pink Panther, Days Of Wine and Roses , Adams, with whom Strouse had written the religious girl” and many others. Many of those films also pro - Broadway shows Bye Bye Birdie, All-American, duced best-selling albums. Mancini not only Golden Boy, It’s A Bird, It’s A Plane, It’s Super - knew how to score a film perfectly, but he was man and others. -

Nothing Sacred (United Artists Pressbook, 1937)

SEE THE BIG FIGHT! DAVID O. SELZNICK’S Sensational Technicolor Comedy NOTHING SACRED WITH CAROLE LOMBARD FREDRIC MARCH CHARLES WINNINCER WALTER CONNOLLY by the producer and director of "A Star is Born■ Directed by WILLIAM A. WELLMAN * Screen play by BEN HECHT * Released thru United Artists Coyrighted MCMXXXVII by United Artists Corporation, New York, N. Y. KNOCKOUT'- * IT'S & A KNOCKOUT TO^E^ ^&re With two great stars 1 about cAROLE {or you to talk, smg greatest comedy LOMBARD, at her top the crest ol pop- role. EREDWC MARC ^ ^ ^feer great ularity horn A s‘* ‘ cWSD.» The power oi triumph in -NOTHING SA oi yfillxanr Selznick production, h glowing beauty oi Wellman direction, combination ^ranced Technicolor {tn star ls . tS made a oi a ^ ““new 11t>en “^ ”«»•>- with selling angles- I KNOCKOUT TO SEE; » It pulls no P“che%afanXioustocount.Beveald laughs that come too to ot Carole Lomb^ mg the gorgeous, gold® the suave chmm ior the fast “JXighest powered rolejhrs oi Fredric March m the g ^ glamorous Jat star has ever had. It 9 J the scieen has great star st unusual story toeS production to th will come m on “IsOVEB:' FASHION PROMOTION ON “NOTHING SACHEH” 1AUNCHING a new type of style promotion on “The centrated in the leading style magazines and papers. And J Prisoner of Zenda,” Selznick International again local distributors of these garments will be well-equipped offers you this superior promotional effort on to go to town with you in a bang-up cooperative campaign “Nothing Sacred.” Through the agency of Lisbeth, on “Nothing Sacred.” In addition, cosmetic tie-ups are nationally famous stylist, the pick of the glamorous being made with one of the country’s leading beauticians. -

INTRODUCTION Fatal Attraction and Scarface

1 introduction Fatal Attraction and Scarface How We Think about Movies People respond to movies in different ways, and there are many reasons for this. We have all stood in the lobby of a theater and heard conflicting opin- ions from people who have just seen the same film. Some loved it, some were annoyed by it, some found it just OK. Perhaps we’ve thought, “Well, what do they know? Maybe they just didn’t get it.” So we go to the reviewers whose business it is to “get it.” But often they do not agree. One reviewer will love it, the next will tell us to save our money. What thrills one person may bore or even offend another. Disagreements and controversies, however, can reveal a great deal about the assumptions underlying these varying responses. If we explore these assumptions, we can ask questions about how sound they are. Questioning our assumptions and those of others is a good way to start think- ing about movies. We will soon see that there are many productive ways of thinking about movies and many approaches that we can use to analyze them. In Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1992), the actor playing Bruce Lee sits in an American movie theater (figure 1.1) and watches a scene from Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) in which Audrey Hepburn’s glamorous character awakens her upstairs neighbor, Mr Yunioshi. Half awake, he jumps up, bangs his head on a low-hanging, “Oriental”-style lamp, and stumbles around his apart- ment crashing into things. -

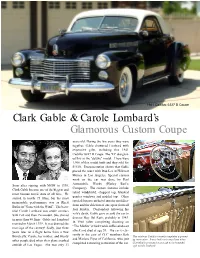

Glamorous Custom Coupe Clark Gable & Carole Lombard's

1941 Cadillac 6227 D Coupe Clark Gable & Carole Lombard’s Glamorous Custom Coupe years old. During the few years they were together, Gable showered Lombard with expensive gifts, including this 1941 Cadillac 6227 D Coupe. The "D" designat- ed this as the "deluxe" model. There were 1,900 of this model built and they sold for $1510. Documentation shows that Gable placed the order with Don Lee at Hillcrest Motors in Los Angeles. Special custom work on the car was done by Earl Automobile Works (Harley Earl’s Soon after signing with MGM in 1930, Company). The custom features include Clark Gable became one of the biggest and raked windshield, chopped top, blanked most famous movie stars of all time. He quarter windows and padded top. Other starred in nearly 75 films, but his most special features included interior modifica- memorable performance was as Rhett tions and the deletion of one spear from all Butler in "Gone with the Wind". The beau- four fenders. Despondent following his tiful Carole Lombard was under contract wife's death, Gable gave or sold the car to with Fox and then Paramount. She starred director Roy Del Ruth, probably in 1943. in more than 80 films. Gable and Lombard In 1960 (after completing shooting on married in March 1939. It was deemed the “The Misfits”) Clark Gable suffered a heart marriage of the century! Sadly, just three attack and died at age 59. The car is cur- years later on a flight home from a War rently in the care of CLC members Bob Bond rally, Carole, her mother, and twenty This celebrity Cadillac recently completed a ground- and Marlene Piper of California, who just other people died when their plane crashed up restoration. -

P E R F O R M I N G

PERFORMING & Entertainment 2019 BOOK CATALOG Including Rowman & Littlefield and Imprints of Globe Pequot CONTENTS Performing Arts & Entertainment Catalog 2019 FILM & THEATER 1 1 Featured Titles 13 Biography 28 Reference 52 Drama 76 History & Criticism 82 General MUSIC 92 92 Featured Titles 106 Biography 124 History & Criticism 132 General 174 Order Form How to Order (Inside Back Cover) Film and Theater / FEATURED TITLES FORTHCOMING ACTION ACTION A Primer on Playing Action for Actors By Hugh O’Gorman ACTION ACTION Acting Is Action addresses one of the essential components of acting, Playing Action. The book is divided into two parts: A Primer on Playing Action for Actors “Context” and “Practice.” The Context section provides a thorough examination of the theory behind the core elements of Playing Action. The Practice section provides a step-by-step rehearsal guide for actors to integrate Playing Action into their By Hugh O’Gorman preparation process. Acting Is Action is a place to begin for actors: a foundation, a ground plan for how to get started and how to build the core of a performance. More precisely, it provides a practical guide for actors, directors, and teachers in the technique of Playing Action, and it addresses a niche void in the world of actor training by illuminating what exactly to do in the moment-to-moment act of the acting task. March, 2020 • Art/Performance • 184 pages • 6 x 9 • CQ: TK • 978-1-4950-9749-2 • $24.95 • Paper APPLAUSE NEW BOLLYWOOD FAQ All That’s Left to Know About the Greatest Film Story Never Told By Piyush Roy Bollywood FAQ provides a thrilling, entertaining, and intellectually stimulating joy ride into the vibrant, colorful, and multi- emotional universe of the world’s most prolific (over 30 000 film titles) and most-watched film industry (at 3 billion-plus ticket sales). -

The Representation of Women in Romantic Comedies Jordan A

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Media and Communication Studies Honors Papers Student Research 4-24-2017 Female Moments / Male Structures: The Representation of Women in Romantic Comedies Jordan A. Scharaga Ursinus College, [email protected] Adviser: Jennifer Fleeger Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/media_com_hon Part of the Communication Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Scharaga, Jordan A., "Female Moments / Male Structures: The Representation of Women in Romantic Comedies" (2017). Media and Communication Studies Honors Papers. 6. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/media_com_hon/6 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media and Communication Studies Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Female Moments/Male Structures: The Representation of Women in Romantic Comedies Jordan Scharaga April 24, 2017 Submitted to the Faculty of Ursinus College in fulfillment of the requirements for Distinguished Honors in the Media and Communication Studies Department. Abstract: Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl again. With this formula it seems that romantic comedies are actually meant for men instead of women. If this is the case, then why do women watch these films? The repetition of female stars like Katharine Hepburn, Doris Day and Meg Ryan in romantic comedies allows audiences to find elements of truth in their characters as they grapple with the input of others in their life choices, combat the anxiety of being single, and prove they are less sexually naïve than society would like to admit. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

The Notorious Ben Hecht

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Book Previews Purdue University Press 3-2019 The otN orious Ben Hecht: Iconoclastic Writer and Militant Zionist Julien Gorbach Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gorbach, Julien, "The otN orious Ben Hecht: Iconoclastic Writer and Militant Zionist" (2019). Purdue University Press Book Previews. 26. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews/26 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. “In The Notorious Ben Hecht: Iconoclastic Writer and Militant Zionist, Julien Gorbach highlights the character, the motivations, and the involvement of an engaged intellectual, crossing from the world of words into that of assertive advocacy on behalf of a cause deemed too narrow for the milieu in which he was a major element. In focusing on this facet of the life of one who was a borderline American Jew, Gorbach not only details the personal biography of Hecht as Hollywood screenwriter, playwright, and novelist, but in his treatment of Hecht’s activities on behalf of the Jewish resistance in Mandate Palestine against the oppressive British rule, he retrieves that period of Israel’s history shunted aside due to ideological and political bias, the years of the national liberation struggle prior to the establishment of the state that have been subjected to a campaign of purposeful neglect and which affected Hecht as well.” —Yisrael Medad, Research Fellow, Menachem Begin Heritage Center, Jerusalem “With storytelling skills equal to his subject’s, Julien Gorbach shows the nuance and complexity of Ben Hecht’s transformation from secular and cynical Hollywood script doctor to committed Zionist activist attempting first to save the Jews of Europe during World War II, and then to found the state of Israel. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Screwball Actress

P a g e SCREWBALL ACTRESS RAY E. BOOMHOWER efore the days of cable and satellite dishes, when there were only three major networks avail able for viewing, one of the few things on television that always sparked my interest was the perennialshowing of old movies, usually on lazy Sunday afternoons. The films ranged from Bud Abbott and Lou Costello meeting a host of monsters (Frankenstein, the WolfMan, the Mummy, and the Invisible Man to name but a few) to the detective adventures of Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce as Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson. My favorites, however, were the sophisticated, and hilarious, screwball comedies produced lly Hollywood studios during the height of the Great Depression in the 1930s and into the early 1940s. These films, which often matched the wits of daz an eccentric Park Avenue family. Bullock hires zlingly daffy females with those of hapless males, fea Parke as the family's new butler and eventually tured the talents of such well known stars as Cary Grant, falls in love with her new "protege." Irene Dunne, Katherine Hepburn, Clark Cable, and Of course, as often happens in these movies, Claudette Colbert. Who hasn't chortled over the bud Parke, representingthe decency and forthright ding romance between a spoiled heiress and a recently ness of the common man, teaches the wealthy fired reporter in It Happened One Night ( 1934), the mis family a thing or twoabout life and saves them understandings between a married couple in TheAwful from disaster. A box-office hit at the time, the Truth (1937), the madcap search for a missing dinosaur movie featured fine acting from not only its bone in Bringing Up Baby ( 1938), and the bizarre machi stars-both Lombard and Powell received nations of a newspaper editor attempting to lure his Academy Award nominations for their per ex-wife back to her former job in His GirlFriday (1940)? formances-but also from its supporting cast. -

In Love in a Movie : Women and Contemporary Romantic Comedy

IN LOVE IN A MOVIE: WOMEN AND CONTEMPORARY ROMANTIC COMEDY By ANDREA ROCHELLE MABRY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2004 Copyright 2004 by Andrea Rochelle Mabry For Olivia and Grace ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is very much a collaborative effort, and for its existence I am indebted to a great many people. I first wish to express my appreciation to the faculty of the University of Florida Department of English, particularly the members of my dissertation committee. Professor Maureen Turim, my advisor and dissertation director, has been an invaluable mentor, not only over the course of this project, but throughout my studies at Florida. Her guidance in the writing of this dissertation, from the original seed of an idea to the final reading, has been invaluable. I am also truly grateful to Professors Susan Hegeman, Roger Beebe, and Nora Alter for their enthusiasm, their advice, and their encouragement to take my work to new levels. My thanks also go out to my fellow graduate students in the Florida English Department for their friendship and their good humor. The camaraderie of other students helped lighten many a stressful day as I worked to complete this journey. Finally, my family—Mom, Dad, Linda, Christine, Tony, Olivia and Grace—have always provided me with love and support, not just as I wrote this dissertation, but all along the road I have taken to get to this point. For that they have my love and my thanks.