The Machine in the Ghost: Writing Women in Supernatural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Analysis of the Roles of Women in the Lais of Marie De France

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1976 Critical analysis of the roles of women in the Lais of Marie de France Jeri S. Guthrie The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Guthrie, Jeri S., "Critical analysis of the roles of women in the Lais of Marie de France" (1976). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1941. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1941 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE ROLES OF WOMEN IN THE LAIS OF MARIE DE FRANCE By Jeri S. Guthrie B.A., University of Montana, 1972 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1976 Approved by: Chairmah, Board of Exami iradua4J^ School [ Date UMI Number EP35846 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT OissHEH'tfttkffl Pk^islw^ UMI EP35846 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). -

Screwball Syll

Webster University FLST 3160: Topics in Film Studies: Screwball Comedy Instructor: Dr. Diane Carson, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course focuses on classic screwball comedies from the 1930s and 40s. Films studied include It Happened One Night, Bringing Up Baby, The Awful Truth, and The Lady Eve. Thematic as well as technical elements will be analyzed. Actors include Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, Clark Gable, and Barbara Stanwyck. Class involves lectures, discussions, written analysis, and in-class screenings. COURSE OBJECTIVES: The purpose of this course is to analyze and inform students about the screwball comedy genre. By the end of the semester, students should have: 1. An understanding of the basic elements of screwball comedies including important elements expressed cinematically in illustrative selections from noteworthy screwball comedy directors. 2. An ability to analyze music and sound, editing (montage), performance, camera movement and angle, composition (mise-en-scene), screenwriting and directing and to understand how these technical elements contribute to the screwball comedy film under scrutiny. 3. An ability to apply various approaches to comic film analysis, including consideration of aesthetic elements, sociocultural critiques, and psychoanalytic methodology. 4. An understanding of diverse directorial styles and the effect upon the viewer. 5. An ability to analyze different kinds of screwball comedies from the earliest example in 1934 through the genre’s development into the early 40s. 6. Acquaintance with several classic screwball comedies and what makes them unique. 7. An ability to think critically about responses to the screwball comedy genre and to have insight into the films under scrutiny. -

Nothing Sacred (United Artists Pressbook, 1937)

SEE THE BIG FIGHT! DAVID O. SELZNICK’S Sensational Technicolor Comedy NOTHING SACRED WITH CAROLE LOMBARD FREDRIC MARCH CHARLES WINNINCER WALTER CONNOLLY by the producer and director of "A Star is Born■ Directed by WILLIAM A. WELLMAN * Screen play by BEN HECHT * Released thru United Artists Coyrighted MCMXXXVII by United Artists Corporation, New York, N. Y. KNOCKOUT'- * IT'S & A KNOCKOUT TO^E^ ^&re With two great stars 1 about cAROLE {or you to talk, smg greatest comedy LOMBARD, at her top the crest ol pop- role. EREDWC MARC ^ ^ ^feer great ularity horn A s‘* ‘ cWSD.» The power oi triumph in -NOTHING SA oi yfillxanr Selznick production, h glowing beauty oi Wellman direction, combination ^ranced Technicolor {tn star ls . tS made a oi a ^ ““new 11t>en “^ ”«»•>- with selling angles- I KNOCKOUT TO SEE; » It pulls no P“che%afanXioustocount.Beveald laughs that come too to ot Carole Lomb^ mg the gorgeous, gold® the suave chmm ior the fast “JXighest powered rolejhrs oi Fredric March m the g ^ glamorous Jat star has ever had. It 9 J the scieen has great star st unusual story toeS production to th will come m on “IsOVEB:' FASHION PROMOTION ON “NOTHING SACHEH” 1AUNCHING a new type of style promotion on “The centrated in the leading style magazines and papers. And J Prisoner of Zenda,” Selznick International again local distributors of these garments will be well-equipped offers you this superior promotional effort on to go to town with you in a bang-up cooperative campaign “Nothing Sacred.” Through the agency of Lisbeth, on “Nothing Sacred.” In addition, cosmetic tie-ups are nationally famous stylist, the pick of the glamorous being made with one of the country’s leading beauticians. -

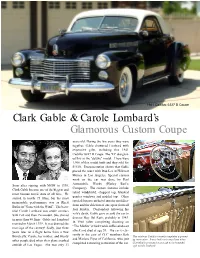

Glamorous Custom Coupe Clark Gable & Carole Lombard's

1941 Cadillac 6227 D Coupe Clark Gable & Carole Lombard’s Glamorous Custom Coupe years old. During the few years they were together, Gable showered Lombard with expensive gifts, including this 1941 Cadillac 6227 D Coupe. The "D" designat- ed this as the "deluxe" model. There were 1,900 of this model built and they sold for $1510. Documentation shows that Gable placed the order with Don Lee at Hillcrest Motors in Los Angeles. Special custom work on the car was done by Earl Automobile Works (Harley Earl’s Soon after signing with MGM in 1930, Company). The custom features include Clark Gable became one of the biggest and raked windshield, chopped top, blanked most famous movie stars of all time. He quarter windows and padded top. Other starred in nearly 75 films, but his most special features included interior modifica- memorable performance was as Rhett tions and the deletion of one spear from all Butler in "Gone with the Wind". The beau- four fenders. Despondent following his tiful Carole Lombard was under contract wife's death, Gable gave or sold the car to with Fox and then Paramount. She starred director Roy Del Ruth, probably in 1943. in more than 80 films. Gable and Lombard In 1960 (after completing shooting on married in March 1939. It was deemed the “The Misfits”) Clark Gable suffered a heart marriage of the century! Sadly, just three attack and died at age 59. The car is cur- years later on a flight home from a War rently in the care of CLC members Bob Bond rally, Carole, her mother, and twenty This celebrity Cadillac recently completed a ground- and Marlene Piper of California, who just other people died when their plane crashed up restoration. -

Violation of Women's Rights: a Cause and Consequence of Trafficking In

violation of women’s rights A cause and consequence of traffi cking in women La Strada International Violation of Women’s Rights A cause and consequence of trafficking in women ‘Violation of women’s rights: a cause and consequence of traffi cking in women’ is produced by La Strada International (lsi), which is a network of nine independent human rights ngos (Non-Governmental Organisations) in Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Macedo- nia, Moldova, the Netherlands, Poland and Ukraine. © La Strada International (lsi) Amsterdam, 8 March 2008 www.lastradainternational.org Text: Bregje Blokhuis Cover logo design: Fame, Bulgaria Cover design: Charley Klinkenberg English editing: Katrin and Brian McGauran Layout: Sander Pinkse Boekproductie The author would like to thank everybody who contributed to this report. All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of lsi as the source. This publication and its dissemination would not have been possible without the generous support of Cordaid and Mama Cash, and lsi’s donors: Foundation doen, icco and the Sigrid Rausing Trust. the sigrid rausing trust Table of contents Foreword 7 Acronyms 8 Terminology 9 Executive summary 11 Recommendations 17 1 Introduction 21 2 Human traffi cking in the La Strada countries 25 2.1 What is traffi cking in human beings? 25 2.2 The scope of traffi cking in human beings 29 2.3 Traffi cking -

Film Gender Report 2012-2016

AUSTRIAN FILM GENDER REPORT KEY RESULTS AUSTRIAN FILM GENDER REPORT 2012-2016 Key Results May 2018 (English version: September 2019) COMMISSIONERS Austrian Film Institute (Österreichisches Filminstitut; ÖFI) https://equality.filminstitut.at/ Austrian Federal Chancellery, Division II: Arts and Culture https://www.kunstkultur.bka.gv.at/ CONTENT RESPONSIBILITY Iris Zappe-Heller and Birgit Moldaschl (Austrian Film Institute) Barbara Fränzen (Austrian Federal Chancellery, Division II: Arts and Culture) SCIENTIFIC STUDY University of Vienna, Department of Sociology Eva Flicker, [email protected], http://www.soz.univie.ac.at/eva-flicker Lena Lisa Vogelmann, [email protected] CONTENTS 4 INTRODUCTION 5 DATA BASE 6 PUBLIC FILM FUNDING: GENDER BUDGETING Film funding: Script development, project development, production Production funding: Funding amounts Distribution funding: Cinema release Funding of vocational training The decision-making bodies of the Austrian Film Institute 14 FILM CREW FEES Remuneration in the field of cinema Remuneration in the field of television 18 HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS AND MAIN CHARACTERS 20 CINEMA FEATURE FILMS OFF SCREEN Women and men in department head positions Shares of women/men in department head positions Female and male directors Directing and film crew 22 CINEMA FEATURE FILMS ON SCREEN: GENDER ON SCREEN The Bechdel-Wallace test Main characters in released cinema feature films, 2012-2016 Comments on the film characters’ physical attractiveness Sexualised violence 27 FILM FESTIVALS IN AUSTRIA: FESTIVAL -

NWP Newsletter

Newsletter: NWP FOCUS News from the Network Women’s Program Issue 1, 1998 (Contact: [email protected]) Inside this issue: 1. NWP and GSN Run the Transnational Training Seminar on Trafficking in Women 2. NWP Initiatives 3. La Strada, Ukraine Fights Trafficking in Women 4. Romany Women Meet to Identify Issues 5. The Women's Program of OSF-Albania 6. NWP Holds Its First Women's Human Rights Training 7. The East East Program Focuses on Women's Issues 8. Upcoming NWP Events 1. NWP and GSN Run the Transnational Training Seminar on Trafficking in Women "I want the United Nations to be involved, I want to raise global awareness of how serious the problem is," declared Mary Robinson, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, about the issue of trafficking in women. Susan Soros introduced Robinson who addressed the representatives of over 100 NGOs from 37 countries at the Transnational Training Seminar on Trafficking in Women coordinated by the Network Women's Program and the Global Survival Network, June 20-24, in Budapest. Trafficking women for the sex trade puts hundreds of thousands of women throughout the world at risk of losing their personal freedom, suffering physical and emotional harm, working in degrading and sometimes life-threatening situations, and being cheated of their earnings. Wishing to flee economic hardships, unsuspecting women answer advertisements to work abroad as waitresses, models and cooks. They often sign a contract with a trafficker stating the debt owed and the responsibility to work until it is paid off. Once a woman arrives in the receiving country, her passport is confiscated, and she is forced into prostitution. -

An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers Cultural Analysis and Social Theory 8-2018 Queering Player Agency and Paratexts: An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games Jessica Kathryn Needham Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cast_mrp Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Needham, Jessica Kathryn, "Queering Player Agency and Paratexts: An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games" (2018). Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers. 6. https://scholars.wlu.ca/cast_mrp/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cultural Analysis and Social Theory at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Queering player agency and paratexts: An analysis and expansion of queerbaiting in video games by Jessica Kathryn Needham Honours Rhetoric and Professional Writing, Arts and Business, University of Waterloo, 2016 Major Research Paper Submitted to the M.A. in Cultural Analysis and Social Theory in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts Wilfrid Laurier University 2018 © Jessica Kathryn Needham 2018 1 Abstract Queerbaiting refers to the way that consumers are lured in with a queer storyline only to have it taken away, collapse into tragic cliché, or fail to offer affirmative representation. Recent queerbaiting research has focused almost exclusively on television, leaving gaps in the ways queer representation is negotiated in other media forms. -

Forbidden Faces: Effects of Taliban Rule

Forbidden Faces: Effects of Taliban Rule on Women in Afghanistan Overview In this lesson, students will explore the rise of Taliban power in Afghanistan and the impacts of Taliban rule upon Afghan women. Grade 9 North Carolina Essential Standards for World History • WH.8.3 ‐ Explain how liberal democracy, private enterprise and human rights movements have reshaped political, economic and social life in Africa, Asia, Latin America, Europe, the Soviet Union and the United States (e.g., U.N. Declaration of Human Rights, end of Cold War, apartheid, perestroika, glasnost, etc.). • WH.8.4‐ Explain why terrorist groups and movements have proliferated and the extent of their impact on politics and society in various countries (e.g., Basque, PLO, IRA, Tamil Tigers, Al Qaeda, Hamas, Hezbollah, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, etc.). Essential Questions • What is the relationship between Islam and the Taliban? • How does the Taliban try to control Afghan women? • How has the experience of Afghan women changed with the Taliban’s emergence? • What was the United States’ role in the Taliban coming to power? • How is clothing used as a means of oppression in Afghanistan? Materials • Overhead or digital projector • Post Its (four per student) • Value statements written on poster or chart paper: 1. I am concerned about being attacked by terrorists. 2. America has supported the Taliban coming into power. 3. All Muslims (people practicing Islam) support the Taliban. 4. I know someone currently deployed in Iraq or Afghanistan. • Opinion scale for each value statement -

Roma Screenplay

IN ENGLISH ROMA Written and Directed by Alfonso Cuarón Dates in RED are meant only as a tool for the different departments for the specific historical accuracy of the scenes and are not intended to appear on screen. Thursday, September 3rd, 1970 INT. PATIO TEPEJI 21 - DAY Yellow triangles inside red squares. Water spreading over tiles. Grimy foam. The tile floor of a long and narrow patio stretching through the entire house: On one end, a black metal door gives onto the street. The door has frosted glass windows, two of which are broken, courtesy of some dejected goalee. CLEO, Cleotilde/Cleodegaria Gutiérrez, a Mixtec indigenous woman, about 26 years old, walks across the patio, nudging water over the wet floor with a squeegee. As she reaches the other end, the foam has amassed in a corner, timidly showing off its shiny little white bubbles, but - A GUSH OF WATER surprises and drags the stubborn little bubbles to the corner where they finally vanish, whirling into the sewer. Cleo picks up the brooms and buckets and carries them to - THE SMALL PATIO - Which is enclosed between the kitchen, the garage and the house. She opens the door to a small closet, puts away the brooms and buckets, walks into a small bathroom and closes the door. The patio remains silent except for a radio announcer, his enthusiasm melting in the distance, and the sad song of two caged little birds. The toilet flushes. Then: water from the sink. A beat, the door opens. Cleo dries her hands on her apron, enters the kitchen and disappears behind the door connecting it to the house. -

Ben-Hur Trivia

IMDb All | IMDb Apps | Help Movies, TV Celebs, Events News & & & Photos Community Watchlist Login Showtimes Edit Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925) Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ Trivia Did You Know? Trivia Goofs Crazy Credits Showing all 38 items Quotes Alternate Versions Connections Despite the fact that there is nudity in this film, it was passed by censors of that time Soundtracks because it dealt with Christianity, as it was originating. 9 of 10 found this interesting | Share this Explore More Share this page: The troubled Italian set was eventually torn down and a new one built in Culver City, California. The famed chariot race was shot with 42 cameras were and 50,000 feet of film consumed. Second-unit director B. Reeves Eason offered a bonus to the winning driver. Like You and 217 others like this.217 people like The final pile-up was filmed later. No humans were seriously injured during the US Like this. Sign Up to see what your friends like. production, but several horses were killed. 7 of 8 found this interesting | Share this User Lists Create a list » Future stars Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Joan Crawford, and Myrna Loy were uncredited Related lists from IMDb users extras in the chariot race scenes. Crawford and Loy also played slave girls. (ebop) 2015 Seen Movies: 1925 7 of 8 found this interesting | Share this 5, v. Google a list of 35 titles on June created 31 May 2012 in Garcia According to The Guinness Book of World Records (2002), thearchived movie contains the most edited scene in cinema history. -

The Bicycle Thief

The Bicycle Thief Roger Ebert / Jan 1, 1949 "The Bicycle Thief" is so well-entrenched as an official masterpiece that it is a little startling to visit it again after many years and realize that it is still alive and has strength and freshness. Given an honorary Oscar in 1949, routinely voted one of the greatest films of all time, revered as one of the foundation stones of Italian neorealism, it is a simple, powerful film about a man who needs a job. The film, now being re-released in a new print to mark its 50s anniversay, was directed by Vittorio De Sica, who believed that everyone could play one role perfectly: himself. It was written by Cesare Zavattini, the writer associated with many of the great European directors of the 1940s through the 1970s. In his journals, Zavattini writes about how he and De Sica visited a brothel to do research for the film--and later the rooms of the Wise Woman, a psychic, who inspires one of the film's characters. What we gather from these entries is that De Sica and his writer were finding inspiration close to the ground in those days right after the war, when Italy was paralyzed by poverty. The story of "The Bicycle Thief" is easily told. It stars Lamberto Maggiorani, not a professional actor, as Ricci, a man who joins a hopeless queue every morning looking for work. One day there is a job--for a man with a bicycle. "I have a bicycle!" Ricci cries out, but he does not, for it has been pawned.