University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building NIGER

Co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union LAW ENFORCEMENT TRAINING FOR CAPACITY BUILDING LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building NIGER Downloadable Country Booklet DL. 2.5 (Ve 1.2) Dissemination level: PU Let4Cap Grant Contract no.: HOME/ 2015/ISFP/AG/LETX/8753 Start date: 01/11/2016 Duration: 33 months Dissemination Level PU: Public X PP: Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission) RE: Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission) Revision history Rev. Date Author Notes 1.0 20/03/2018 SSSA Overall structure and first draft 1.1 06/05/2018 SSSA Second version after internal feedback among SSSA staff 1.2 09/05/2018 SSSA Final version version before feedback from partners LET4CAP_WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable_2.5 VER1.2 WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable Deliverable 2.5 Downloadable country booklets VER V. 1 . 2 2 NIGER Country Information Package 3 This Country Information Package has been prepared by Eric REPETTO and Claudia KNERING, under the scientific supervision of Professor Andrea de GUTTRY and Dr. Annalisa CRETA. Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy www.santannapisa.it LET4CAP, co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union, aims to contribute to more consistent and efficient assistance in law enforcement capacity building to third countries. The Project consists in the design and provision of training interventions drawn on the experience of the partners and fine-tuned after a piloting and consolidation phase. © 2018 by LET4CAP All rights reserved. 4 Table of contents 1. Country Profile 1.1Country in Brief 1.2Modern and Contemporary History of Niger 1.3 Geography 1.4Territorial and Administrative Units 1.5 Population 1.6Ethnic Groups, Languages, Religion 1.7Health 1.8Education and Literacy 1.9Country Economy 2. -

Eu Pressure on Niger to Stop Migrants Is Reshaping Cross-Border Economies

DIIS POLICY BRIEF DECEMBER 2019 From migrants to drugs, gold, and rare animals EU PRESSURE ON NIGER TO STOP MIGRANTS IS RESHAPING CROSS-BORDER ECONOMIES Though the four-by-fours with migrants still POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS leave regularly for Libya, there’s little doubt that EU driven anti-migration efforts in the Agadez ■ EU interventions in Niger have had an unintended region of Niger has been a blow to the local negative effect on the safety of migrants. It’s cross-border economy. therefore important to maintain focus on rescue missions in the desert. Official discourse claims that migration to Libya from ■ Europe must ensure that conflict and context Niger has dropped by 90 percent, following the 2016 sensitivity remain paramount as well as promoting crackdown on the migration business in Agadez. These alternative development opportunities and good statistics are difficult to back up given that drivers now governance. leave at night and under the radar. They drive without ■ National, local and traditional authorities should lights on and take more dangerous routes and rough continue to avoid conflicts linked to natural backroads into Libya. “There’s not just one way to resources, including gold, uranium, pasturelands Libya. There are a thousand ways to Libya,” as one and water, by promoting transparency and partici- driver in Agadez explained on one of our numerous patory decision-making. field trips to the Agadez region. “There’s not just one way to Libya. There are a thousand ways to Libya,” Some humanitarian actors estimate that the crossing of the desert may yield even more fatalities than the crossing of the sea Yet, EUs border externalization is clearly having an On the backroads of the southern Central Sahara, effect on the region, and many observers had predict- migrants and drivers risk being ambushed or running ed a breakdown in the historically turbulent relation- into arbitrary check points. -

ECFG-Niger-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment (Photos courtesy of IRIN News 2012 © Jaspreet Kindra). Niger Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Niger, focusing on unique cultural features of Nigerien society and is designed to complement other pre- deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

NIGER Enhanced Food Security Monitoring January 11, 2010

NIGER Enhanced Food Security Monitoring January 11, 2010 Objective of this monitoring: Between December 2009 and March 2010, to more regularly monitor key features of Niger’s current and near‐future food security to inform decision‐making related to external assistance. Off‐season and flood recession agriculture • Dams and depressions normally used for off‐season cropping were generally not well filled compared to normal, which resulted in the abandonment of several irrigation sites. Approximately 1,745 hectares are projected to be cultivated in vegetable crops, benefitting 60,800 producers in 544 sites, including 71 sites developed with support from FAO. The area planted is down between 5‐10 percent compared to normal due early depletion of ponds. The area planted is down as much as 30 percent from average in Goroubéri (Commune 1 of Niamey), Tchia, Kagari, Boubout (Mirriah), Tam (Mainé Soroa), and Bosso (Diffa). Two or three vegetable harvests are possible in a normal year, but this year water will be scarce as of February, thereby reducing the production cycle and number of potential harvests. • The winter irrigated rice harvest has just finished and is near 2008 levels. The 2010 dry season is being transplanted, and the Federation of Unions of Rice‐Producer Cooperatives (FUCOPRI) plans to put 3,000 tons of fertilizers at its disposition. However, the encroachment of sand is likely to reduce production. • {No change from previous report} Prices for vegetable products are also above their levels of last year with possible positive effects on vegetable to cereal terms of trade. For example, in Mirriah (Zinder) the price of tomatoes was 100 FCFA/kg in December 2008, and 100 kg of tomatoes could purchase 59 kg of millet. -

F:\Niger En Chiffres 2014 Draft

Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 1 Novembre 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Direction Générale de l’Institut National de la Statistique 182, Rue de la Sirba, BP 13416, Niamey – Niger, Tél. : +227 20 72 35 60 Fax : +227 20 72 21 74, NIF : 9617/R, http://www.ins.ne, e-mail : [email protected] 2 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Pays : Niger Capitale : Niamey Date de proclamation - de la République 18 décembre 1958 - de l’Indépendance 3 août 1960 Population* (en 2013) : 17.807.117 d’habitants Superficie : 1 267 000 km² Monnaie : Francs CFA (1 euro = 655,957 FCFA) Religion : 99% Musulmans, 1% Autres * Estimations à partir des données définitives du RGP/H 2012 3 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 4 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Ce document est l’une des publications annuelles de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Il a été préparé par : - Sani ALI, Chef de Service de la Coordination Statistique. Ont également participé à l’élaboration de cette publication, les structures et personnes suivantes de l’INS : les structures : - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Economiques (DSEE) ; - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Démographiques et Sociales (DSEDS). les personnes : - Idrissa ALICHINA KOURGUENI, Directeur Général de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Ibrahim SOUMAILA, Secrétaire Général P.I de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Ce document a été examiné et validé par les membres du Comité de Lecture de l’INS. Il s’agit de : - Adamou BOUZOU, Président du comité de lecture de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Djibo SAIDOU, membre du comité - Mahamadou CHEKARAOU, membre du comité - Tassiou ALMADJIR, membre du comité - Halissa HASSAN DAN AZOUMI, membre du comité - Issiak Balarabé MAHAMAN, membre du comité - Ibrahim ISSOUFOU ALI KIAFFI, membre du comité - Abdou MAINA, membre du comité. -

Insecurity, Terrorism, and Arms Trafficking in Niger

Small Arms Survey Maison de la Paix Report Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E January 1202 Geneva 2018 Switzerland t +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 e [email protected] At the Crossroads of Sahelian Conflicts Sahelian of the Crossroads At About the Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is a global centre of excellence whose mandate is to generate impar- tial, evidence-based, and policy-relevant knowledge on all aspects of small arms and armed AT THE CROSSROADS OF violence. It is the principal international source of expertise, information, and analysis on small arms and armed violence issues, and acts as a resource for governments, policy- makers, researchers, and civil society. It is located in Geneva, Switzerland, at the Graduate SAHELIAN CONFLICTS Institute of International and Development Studies. The Survey has an international staff with expertise in security studies, political science, Insecurity, Terrorism, and law, economics, development studies, sociology, and criminology, and collaborates with a network of researchers, partner institutions, non-governmental organizations, and govern- Arms Trafficking in Niger ments in more than 50 countries. For more information, please visit: www.smallarmssurvey.org. Savannah de Tessières A publication of the Small Arms Survey/SANA project, with the support of the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Global Affairs Canada, and the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs A T THE CROSSROADS OF SAHELian CONFLictS Insecurity, Terrorism, and Arms Trafficking in Niger Savannah de Tessières A publication of the Small Arms Survey/SANA project, with the support of the Netherlands Min. of Foreign Affairs, Global Affairs Canada, & the Swiss Federal Dept. -

Karsterscheinungen in Nichtkarbonatischen Gesteinen Der Östlichen Republik Niger

WÜRZBURGER GEOGRAPHISCHE ARBEITEN Mitteilungen der Geographischen Gesellschaft Würzburg Herausgeber: D. Böhn - H. Hagedorn - H. Jäger - H.-G. Wagner Schriftleitung: U. Glaser Heft 75 Karsterscheinungen in nichtkarbonatischen Gesteinen der östlichen Republik Niger Barbara Sponholz Würzburg 1989 Im Selbstverlag des Instituts für Geographie der Universität Würzburg in Verbindung mit der Geographischen Gesellschaft Würzburg Druck: Böhler-Verlag GmbH, Seilerstr. 10,8700 WOrzburg Bezug: Institut tOr Geographie der Universität WOrzburg, Am Hubland, 8700 WOrzburg © Alle Rechte vorbehalten ISSN: 0510-9833 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Würzburg. Vorwort Die in der vorliegenden Arbeit vorgestellten Untersuchungen basieren auf mehreren For schungsreisen in die Republik Niger in den Jahren 1986 und 1987. Eine erste Reise im Frühjahr 1986 unter Leitung von Herrn Prof. Dr. H. Hagedorn und Herrn Prof. Dr. D. Bu sche, Würzburg, führte in das Massif de Termit, wo erstmals umfassende Aufnahmen des dortigen Karstformenschatzes in Sandsteinen und Eisenkrusten durchgeführt wurden. Bereits im August 1986 bestand die Möglichkeit zur Teilnahme an einem weiteren Geländeaufenthalt in Niger unter Leitung von Herrn Prof. Dr. J. Grunert, Bonn. Schwer punkt dieser Reise waren das südliche Air und dessen Vorland mit der Stufe von Tiguidit sowie das Massif de Koutous im Süden Landes und die Kristallingebiete um Goure und Zinder. Unmittelbar anschließend bot sich im Herbst 1986 die Gelegenheit, unter Leitung von Herrn Prof. Dr. D. Busche den Nordteil des Arbeitsgebietes (Tenere, Stufe von Bilma, Djado) kennenzulernen. Die Arbeiten in diesem Raum konnten im Frühjahr 1987 wäh• rend der dritten Forschungsreise unter Leitung von Herrn Prof. Dr. H. Hagedorn und Herrn Prof. Dr. D. Busche wesentlich ergänzt werden. An den genannten Forschungsaufenthalten nahmen von deutscher Seite aus - bei wechselnder Zusammensetzung der Arbeitsgruppe - Dr. -

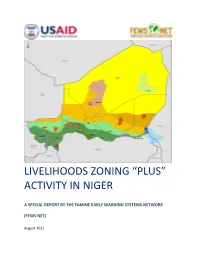

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

Population Movement

DREF final report Niger: Population Movement DREF operation n° MDRNE007 GLIDE n° OT-2011-000064-NER 27 March, 2012 The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. Summary: CHF 250,318 was allocated from the IFRC’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) on 08 June, 2011 to support the Red Cross Society of Niger (RCSN) in delivering assistance to some 4,270 families (29,890 beneficiaries). Northern Niger is the gateway for young sub-sahelian people leaving their country to seek better living conditions in the Maghreb and European countries. Crossing the desert that covers both borders between Libya and Niger is a big challenge, and many migrants die before reaching Libya. Some of those who manage to reach Libya are pushed back to the borders with Niger without their belongings. The northern village of Dirkou Nigeriens returnees after the uprising in Libya. is a focal point for such movements. RCSN/IFRC. Population movements reached crisis proportions due to the dramatic events in Libya during 2011. According to IOM and the local branch of the RCSN in Dirkou, since 2009 a monthly average of 150 persons expelled from Libya were transiting through Dirkou to return home. Following the 2011 uprising in Libya, the number of refugees/returnees increased to 850 per day by March 2011. -

Niger Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals. September 2017

NIGER STAPLE FOOD AND LIVESTOCK MARKET FUNDAMENTALS SEPTEMBER 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgements FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Niger who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. Cover photos @ FEWS NET and Flickr Creative Commons. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Members of Special Committee: Dr. DG Sisler Dr. TT Poleman

NIA1MEY DEPARTMENT T)EVELOPMENT PROJ17CT: MANAGING RURAL DEVELOPMENT WITH MINIMAL EVIDENCE A Project Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell 'nivers''ty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Professional Studies (Agriculture) by Mark Gregory Wentling August 1983 Members of Special Committee: Dr. D.G. Sisler Dr. T.T. Poleman ABSTRACT Managers of agricultural projects in developing countries need farm level information that is useful and timely. Large-scale efforts are frequently undertaken to obtain this information. These efforts are often costly and cumbersome to execute. They alsc may produce a large amount of information that is inconsequential to project operations. Moreover, much of the essential information generated by these efforts arrives too late to be of any use in making key project decisions. This paper uses the case of the Niamey Department Development Project in the Republic of Niger to illustrate how a minimal amount of easily obtainable data can often be adequate to implement a new project or effectively manage an on-going program., Drawing upon his own experience with this project, the author describes how this simple, common-sense approach was used to assist with the administration of this complex, regional development project. The author relates the many insights gained by the application of this approach and the problems involved with collecting farm-level data under uncertain agricultural conditions in a resource-rpoor country. The author recommends this approach for areas where little concrete information is available, especially those situations which call for an inexpensive means of quickly identifying principal farming practices and important con straints to improving major cropping systems.