An Ax to Grind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hand Saws Hand Saws Have Evolved to fill Many Niches and Cutting Styles

Source: https://www.garagetooladvisor.com/hand-tools/different-types-of-saws-and-their-uses/ Hand Saws Hand saws have evolved to fill many niches and cutting styles. Some saws are general purpose tools, such as the traditional hand saw, while others were designed for specific applications, such as the keyhole saw. No tool collection is complete without at least one of each of these, while practical craftsmen may only purchase the tools which fit their individual usage patterns, such as framing or trim. Back Saw A back saw is a relatively short saw with a narrow blade that is reinforced along the upper edge, giving it the name. Back saws are commonly used with miter boxes and in other applications which require a consistently fine, straight cut. Back saws may also be called miter saws or tenon saws, depending on saw design, intended use, and region. Bow Saw Another type of crosscut saw, the bow saw is more at home outdoors than inside. It uses a relatively long blade with numerous crosscut teeth designed to remove material while pushing and pulling. Bow saws are used for trimming trees, pruning, and cutting logs, but may be used for other rough cuts as well. Coping Saw With a thin, narrow blade, the coping saw is ideal for trim work, scrolling, and any other cutting which requires precision and intricate cuts. Coping saws can be used to cut a wide variety of materials, and can be found in the toolkits of everyone from carpenters and plumbers to toy and furniture makers. Crosscut Saw Designed specifically for rough cutting wood, a crosscut saw has a comparatively thick blade, with large, beveled teeth. -

Active Extensional Faults in the Central-Eastern Iberian Chain, Spain

ISSN (print): 1698-6180. ISSN (online): 1886-7995 www.ucm.es/info/estratig/journal.htm Journal of Iberian Geology 38 (1) 2012: 127-144 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_JIGE.2012.v38.n1.39209 Active extensional faults in the central-eastern Iberian Chain, Spain Fallas activas extensionales en la Cordillera Ibérica centro-oriental J.L. Simón*, L.E. Arlegui, P. Lafuente, C.L. Liesa Dpt. Ciencias de la Tierra, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Zaragoza, c/ Pedro Cerbuna 12, E-50009 Zaragoza, Spain [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] *Corresponding author Received: 27/06/2011 / Accepted: 29/02/2012 Abstract Among the conspicuous extensional structures that accommodate the onshore deformation of the Valencia Trough at the central- eastern Iberian Chain, a number of large faults show evidence of activity during Pleistocene times. At the eastern boundary of the Jiloca graben, the Concud fault has moved since mid Pliocene times at an average rate of 0.07-0.08 mm/y, while rates from 0.08 to 0.33 mm/y have been calculated using distinct stratigraphic markers of Middle to Late Pleistocene age. A total of nine paleoseisms associated to this fault have been identified between 74.5 and 15 ka BP, with interseismic periods ranging from 4 to 11 ka, estimated coseismic displacements from 0.6 to 2.7 m, and potential magnitudes close to 6.8. The other master faults of the Jiloca graben (Ca- lamocha and Sierra Palomera faults) have also evidence of Pliocene to Late Pleistocene displacement, with average slip rates of 0.06 and 0.11-0.15 mm/y, respectively. -

Fire Bow Drill

Making Fire With The Bow Drill When you are first learning bow-drill fire-making, you must make conditions and your bow drill set such that the chance of getting a coal is the greatest. If you do not know the feeling of a coal beginning to be born then you will never be able to master the more difficult scenarios. For this it is best to choose the “easiest woods” and practice using the set in a sheltered location such as a garage or basement, etc. Even if you have never gotten a coal before, it is best to get the wood from the forest yourself. Getting it from a lumber yard is easy but you learn very little. Also, getting wood from natural sources ensures you do not accidentally get pressure-treated wood which, when caused to smoulder, is highly toxic. Here are some good woods for learning with (and good for actual survival use too): ► Eastern White Cedar ► Staghorn Sumac ► Most Willows ► Balsam Fir ► Aspens and Poplars ► Basswood ► Spruces There are many more. These are centered more on the northeastern forest communities of North America. A good tree identification book will help you determine potential fire-making woods. Also, make it a common practice to feel and carve different woods when you are in the bush. A good way to get good wood for learning on is to find a recently fallen branch or trunk that is relatively straight and of about wrist thickness or bigger. Cut it with a saw. It is best if the wood has recently fallen off the tree. -

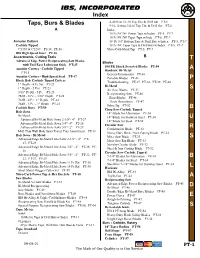

IBS, INCORPORATED T a P S B U R S B L a D E S Index

IBS, INCORPORATED Index 4-40 thru 1/2-10 Tap, Die & Drill Set PT-8 Taps, Burs & Blades 9/16-12 thru 3/4-16 Tap, Die & Drill Set PT-8 A Index 10 Pc NC/NF Power Taps w/Index PT-5, PT-7 10 Pc NC/NF Taper Taps w/Inde PT-5, PT-7 Annular Cutters 18 Pc NC Bottom Taps & Drill Bits w/Index PT-5, PT-7 Carbide Tipped 18 Pc NC Taper Taps & Drill Bits w/Index PT-5, PT-7 CT150 & CT200 PT-14, PT-16 Nitro-Carb Hand Tap PT-5, PT-7 IBS High Speed Steel PT-16 Assortments, Cutting Tools B Advanced Edge Power Reciprocating Saw Blades T Blades with Tool Ease Lubricant Stick PT-45 100 PK Shark Serrated Blades PT-54 Annular Cutters - Carbide Tipped Bandsaw, Bi-Metal A PT-15 General Information PT-36 Annular Cutters - High Speed Steel PT-17 Portable Blades PT-41 P Black Hole Carbide Tipped Cutters Troubleshooting PT-37, PT-38, PT-39, PT-40 1" Depth - 4 Pc.Set PT-23 Bi-Metal 1" Depth - 5 Pcs PT-23 Air Saw Blades PT-51 S 3/16" Depth - 5 Pc. PT-23 Reciprocating Saw PT-46 762R - 5 Pc. - 3/16" Depth PT-22 Boar Blades PT-48 763R - 4 Pc. 1" Depth PT-22 Thick Demolition PT-47 764R - 5 Pc. - 1" Depth PT-23 Sabre/Jig PT-52 Carbide Burs PT-59 Chop Saw-Carbide Tipped B Hole Saws 14" Blade for Aluminum PT-34 Bi-Metal 14" Blade for Stainless Steel PT-34 U Advanced Bi-Metal Hole Saws 2-1/8"- 4" PT-27 14" Blade for Steel PT-34 Advanced Bi-Metal Hole Saws 3/4"- 4" PT-28 Circular Saw Advanced Bi-Metal Hole Saws 5/8"- 2" PT-29 Combination Blade PT-32 R M42 Thin Wall Hole Saws Travel Tray Assortment PT-18 Heavy Duty Deck / Nail Cutting Blade PT-32 Hole Saws - Bi-Metal Miter Saw -

Drying of Pharmaceutical Powders Using an Agitated Filter Dryer

Drying of Pharmaceutical Powders Using An Agitated Filter Dryer Wei Li Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Institute of Particle Science and Engineering December 2014 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Wei Li to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. - ii - Acknowledgements I would first like to express my gratitude to Professor Kevin J. Roberts and Tariq Mahmud for their help and supervision throughout the course of this research work. I very appreciate that I spent such a fulfilled time to work in the field of Chemical Engineering especially in process engineering an area that I am so interested in. I am deeply grateful to them that they introduced me to the field of chemical engineering a discipline that I am much more proficient in. I would also like to thank the technical staff in School of Chemical and Process Engineering, in particular Steve Caddick, Peter Dawson, John Cran and Simon Lloyd for their support in building up the experimental facilities needed for this research as well as for carrying out repairs and relocating to the filter dryer rig. I would also like to extend my appreciation to Stephen Terry from electronics workshop for his help for developing and implementing the LabVIEW system needed to control the experimental rigs used. -

2016-2017 Annual Report Tennessee State University Foundation 2016-2017 BETTER Annual Report

BETTER TOGETHER 2016-2017 Annual Report Tennessee State University Foundation 2016-2017 BETTER Annual Report 4 By the Numbers 6 From the Board Chair 7 From the President 8 Alumni: TOGETHER GIving Where it all Begins 10 Corporations: Generosity is Good Business Just as it takes professors, peers, family, 12 Foundations & Organizations: Missions Aligned and community to shape a student’s path, 14 Faculty, Staff and Friends: A Little Help from our Family & Friends the TSU Foundation relies on a mix of support to serve the University today and in the future. 16 Scholarship Awards 20 Legacy Society Every segment of the donor population serves 21 Giving Societies a special purpose, and every donor plays a 28 Honor Roll of Donors unique role in the great things we achieve. 42 Memorial Gifts 45 Financial Overview 47 Ways to Give We are better together. BY THE NUMBERS 2016-2017 Fundraising Highlights Overall Giving AlumniAlumni GivingGiving $3,569,327.78 8,523 $1,608,150.93 TOTAL CONTRIBUTIONS GIFTS RECEIVED TOTAL ALUMNI GIVING $419 3,542 $271 2,384 AVERAGE GIFT SIZE DONORS AVERAGE GIFT SIZE ALUMNI DONORS $1,008 652 $675 506 AVERAGE ANNUAL CONSECUTIVE DONORS: AVERAGE ANNUAL CONSECUTIVE DONORS: CONTRIBUTION PER DONOR FIVE YEARS OR MORE CONTRIBUTION PER DONOR FIVE YEARS OR MORE $2 to $300,000 1,160 $2 to $300,000 509 GIFT RANGE NEW DONORS GIFT RANGE NEW DONORS 5 $332,500 NEW PLANNED GIFT TOTAL PLANNED GIFT COMMITMENTS COMMITMENTS DR. GLENDA GLOVER ‘74 PRESIDENT TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY Your gifts create pathways of It’s powerful to see how the opportunity for TSU, and those parts work together to create the the University serves. -

COTI Guide to Crew Leadership for Trails

COTI Guide to Crew Leadership for Trails Produced by Colorado Outdoor Training Initiative (COTI) Funded in part by Great Outdoors Colorado (GOCO) through the Colorado State Parks Trails Program. Second printing 2006 Acknowledgements THANK YOU COTI would like to acknowledge the people and organizations that volunteered their time and resources to the research, review, editing and piloting of these training materials. The content and illustrations of this document is a compilation of pre-existing sources, with a majority of the information provided by Larry Lechner, Protected Area Management Services; Crew Leader Manual, 5th Ed., Volunteers for Outdoor Colorado; Trail Construction and Maintenance Notebook. 2000 Ed. USDA Forest Service; and all of the other resources that are referenced at the end of each section. The COTI Instructor’s Guide to Teaching Crew Leadership for Trails was open to a statewide review prior to pilot training and publication. COTI would like to thank everyone who dedicated time to the review process. The following people provided valuable feedback on the project. CURRICULUM COMMITTEE MEMBERS Project Leader: Terry Gimbel, Colorado State Parks Final content editing 2005 Edition: Pamela Packer, COTI 2006 Edition: Hugh Duffy and Hugh Osborne, National Park Service; Mick Syzek, Continental Divide Trail Alliance Alice Freese, Colorado Outdoor Training Initiative Scott Gordon, Bicycle Colorado Sarah Gorecki, Colorado Fourteeners Initiative Jon Halverson, USFS-Medicine Bow-Routt National Forest David Hirt, Boulder County -

Notice of a Collection 01 Perforated Stone Objects, from the Garioch, Aberdeenshire

6 16 PROCEEDING SOCIETYE TH F O S , FEBRUARY 9, 1903. III. NOTICE OF A COLLECTION 01 PERFORATED STONE OBJECTS, FROM THE GARIOCH, ABERDEENSHIRE. BY J. GRAHAM CALLANDER, F.S.A. SOOT. Many perforated article f stono s f greateo e r leso r s antiquity have been found, the use of which we have no difficulty in defining. Among such article e stonar s e axes, stone hammers, whorls, beads d sinkan , - stones for nets or lines; but this collection of perforated stones from Central Aberdeenshire seems to be quite different from any of the recog- nised types. Localities.—The collection, which consist f sixty-fivo s e specimenss ha , been gathered during the last five years in the Garioch district of Aber- deenshire from eight different localitie n fivi s e parishes :—Elevee ar n from Newbigging, parish of Culsalmond ; one is from the Kirkyard of Culsalmond; five are from the adjoining farms of Jericho and Colpy, Culsalmond e froar m o Johnstonetw ; , paris f Leslio hs froi e me ;on Cushieston, parish of Rayne; one is from Lochend, Barra, parish of Bourtie; thre froe ear m Harlaw, paris f Chapeho f Garioco l fortyd an h; - one are from Logie-Elphinstone estate, also in Chapel of Garioch. e specimenth l Al s have bee e ploughnth turney b , p nonu d e having been found associated with burials or dwelling sites; at the same time many flint implements have been foun e localitiemosn th di f o t s named, especiall firste th , n yi third last-mentioned an , d ones, these I believe, , having been more thoroughly searched. -

LP Solidstart LVL Technical Guide

U.S. Technical Guide L P S o l i d S t a r t LV L Technical Guide 2900Fb-2.0E Please verify availability with the LP SolidStart Engineered Wood Products distributor in your area prior to specifying these products. Introduction Designed to Outperform Traditional Lumber LP® SolidStart® Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) is a vast SOFTWARE FOR EASY, RELIABLE DESIGN improvement over traditional lumber. Problems that naturally occur as Our design/specification software enhances your in-house sawn lumber dries — twisting, splitting, checking, crowning and warping — design capabilities. It ofers accurate designs for a wide variety of are greatly reduced. applications with interfaces for printed output or plotted drawings. Through our distributors, we ofer component design review services THE STRENGTH IS IN THE ENGINEERING for designs using LP SolidStart Engineered Wood Products. LP SolidStart LVL is made from ultrasonically and visually graded veneers arranged in a specific pattern to maximize the strength and CODE EVALUATION stifness of the veneers and to disperse the naturally occurring LP SolidStart Laminated Veneer Lumber has been evaluated for characteristics of wood, such as knots, that can weaken a sawn lumber compliance with major US building codes. For the most current code beam. The veneers are then bonded with waterproof adhesives under reports, contact your LP SolidStart Engineered Wood Products pressure and heat. LP SolidStart LVL beams are exceptionally strong, distributor, visit LPCorp.com or for: solid and straight, making them excellent for most primary load- • ICC-ES evaluation report ESR-2403 visit www.icc-es.org carrying beam applications. • APA product report PR-L280 visit www.apawood.org LP SolidStart LVL 2900F -2.0E: AVAILABLE SIZES b FRIEND TO THE ENVIRONMENT LP SolidStart LVL 2900F -2.0E is available in a range of depths and b LP SolidStart LVL is a building material with built-in lengths, and is available in standard thicknesses of 1-3/4" and 3-1/2". -

Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide PMS 210 April 2013 Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide April 2013 PMS 210 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Operations and Workforce Development Committee. Comments regarding the content of this product should be directed to the Operations and Workforce Development Committee, contact and other information about this committee is located on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically from the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: this product replaces PMS 410-1, Fireline Handbook, NWCG Handbook 3, March 2004. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG-authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group,” “NWCG,” and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

Bodyslam from the Top Rope: Unequal Bargaining Power and Professional Wrestling's Failure to Unionize Stephen S

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Entertainment & Sports Law Review 1-1-1995 Bodyslam From the Top Rope: Unequal Bargaining Power and Professional Wrestling's Failure to Unionize Stephen S. Zashin Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umeslr Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Stephen S. Zashin, Bodyslam From the Top Rope: Unequal Bargaining Power and Professional Wrestling's Failure to Unionize, 12 U. Miami Ent. & Sports L. Rev. 1 (1995) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umeslr/vol12/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Entertainment & Sports Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zashin: Bodyslam From the Top Rope: Unequal Bargaining Power and Professi UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI ENTERTAINMENT & SPORTS LAW REVIEW ARTICLES BODYSLAM FROM THE TOP ROPE: UNEQUAL BARGAINING POWER AND PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING'S FAILURE TO UNIONIZE STEPHEN S. ZASHIN* Wrestlers are a sluggish set, and of dubious health. They sleep out their lives, and whenever they depart ever so little from their regular diet they fall seriously ill. Plato, Republic, III I don't give a damn if it's fake! Kill the son-of-a-bitch! An Unknown Wrestling Fan The lights go black and the crowd roars in anticipation. Light emanates only from the scattered popping flash-bulbs. As the frenzy grows to a crescendo, Also Sprach Zarathustra' pierces the crowd's noise. -

Abrasive Wheel Grinder Abrasive Wheels and Grinding Machines Come in Many Styles, Sizes, and Designs

Abrasive wheel grinder Abrasive wheels and grinding machines come in many styles, sizes, and designs. Both bench-style and pedestal (stand) grinders are commonly found in many industries. These grinders often have either two abrasive wheels, or one abrasive wheel and one special-purpose wheel such as a wire brush, buffing wheel, or sandstone wheel. These types of grinders normally come with the manufacturer’s safety guard covering most of the wheel, including the spindle end, nut, and flange DEWALT Industrial Tool Co. projection. These guards must be strong enough to withstand the effects of a bursting wheel. In addi- tion, a tool/work rest and transparent shields are often provided. Hazard Bench-style and pedestal grinders create special safety problems due to the potential of the abrasive wheel shattering; exposed rotating wheel, flange, and spindle end; and a naturally occurring nip point that is created by the tool/work rest. This is in addition to such concerns as flying fragments, sparks, air contaminants, etc. Cutting, polishing, and wire buffing wheels can create many of the same hazards. Grinding machines are powerful and are designed Exposed spindle end, flange, and nut. No tool/workrest. to operate at very high speeds. If a grinding wheel shatters while in use, the fragments can travel at more than 300 miles per hour. In addition, the wheels found on these machines (abrasive, polishing, wire, etc.) often rotate at several thousand rpms. The potential for serious injury from shooting fragments and the rotating wheel assemblies (including the flange, spindle end, and nut) is great. To ensure that grinding wheels are safely used in your work- place, know the hazards and how to control them.