The Striking of Proof and Pattern Coins in the Eighteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Concepts of 'Sovereign' and 'Great' Orders

ON THE CONCEPTS OF ‘SOVEREIGN’ AND ‘GREAT’ ORDERS Antti Matikkala The only contemporary order of knighthood to include the word ‘sovereign’ in its name is the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and Malta. Sovereignty is here heraldically exemplified by the Grand Master’s use of the closed crown. Its Constitutional Charter and Code explains that the order ‘be- came sovereign on the islands of Rhodes and later of Malta’, and makes the follow- ing statement about its sovereignty: ‘The Order is a subject of international law and exercises sovereign functions.’1 However, the topic of this article is not what current scholarship designates as military-religious orders of knighthood, or simply military orders, but monarchical orders. To quote John Anstis, Garter King of Arms,2 a monarchical order can be defined in the following terms: a Brotherhood, Fellowship, or Association of a certain Number of actual Knights; sub- jected under a Sovereign, or Great Master, united by particular Laws and Statutes, peculiar to that Society, not only distinguished by particular Habits, Ensigns, Badges or Symbols, which usually give Denomination to that Order; but having a Power, as Vacancies happen in their College, successively, of nominating, or electing proper Per- sons to succeed, with Authority to assemble, and hold Chapters. The very concept of sovereignty is ambiguous. A recent collection of essays has sought to ‘dispel the illusion that there is a single agreed-upon concept of sovereignty for which one could offer of a clear definition’.3 To complicate the issue further, historical and theoretical discussions on sovereignty, including those relating to the Order of Malta, concentrate mostly on its relation to the modern concept of state, leaving the supposed sovereignty of some of the monarchical orders of knighthood an unexplored territory. -

The Livery Collar: Politics and Identity in Fifteenth-Century England

The Livery Collar: Politics and Identity in Fifteenth-Century England MATTHEW WARD, SA (Hons), MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy AUGUST 2013 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, lS23 7BQ www.bl.uk ANY MAPS, PAGES, TABLES, FIGURES, GRAPHS OR PHOTOGRAPHS, MISSING FROM THIS DIGITAL COPY, HAVE BEEN EXCLUDED AT THE REQUEST OF THE UNIVERSITY Abstract This study examines the social, cultural and political significance and utility of the livery collar during the fifteenth century, in particular 1450 to 1500, the period associated with the Wars of the Roses in England. References to the item abound in government records, in contemporary chronicles and gentry correspondence, in illuminated manuscripts and, not least, on church monuments. From the fifteenth century the collar was regarded as a potent symbol of royal power and dignity, the artefact associating the recipient with the king. The thesis argues that the collar was a significant aspect of late-medieval visual and material culture, and played a significant function in the construction and articulation of political and other group identities during the period. The thesis seeks to draw out the nuances involved in this process. It explores the not infrequently juxtaposed motives which lay behind the king distributing livery collars, and the motives behind recipients choosing to depict them on their church monuments, and proposes that its interpretation as a symbol of political or dynastic conviction should be re-appraised. After addressing the principal functions and meanings bestowed on the collar, the thesis moves on to examine the item in its various political contexts. -

Creation of Order of Chivalry Page 0 of 72

º Creation of Order of Chivalry Page 0 of 72 º PREFACE Knights come in many historical forms besides the traditional Knight in shining armor such as the legend of King Arthur invokes. There are the Samurai, the Mongol, the Moors, the Normans, the Templars, the Hospitaliers, the Saracens, the Teutonic, the Lakota, the Centurions just to name a very few. Likewise today the Modern Knight comes from a great variety of Cultures, Professions and Faiths. A knight was a "gentleman soldier or member of the warrior class of the Middle Ages in Europe. In other Indo-European languages, cognates of cavalier or rider French chevalier and German Ritter) suggesting a connection to the knight's mode of transport. Since antiquity a position of honor and prestige has been held by mounted warriors such as the Greek hippeus and the Roman eques, and knighthood in the Middle Ages was inextricably linked with horsemanship. Some orders of knighthood, such as the Knights Templar, have themselves become the stuff of legend; others have disappeared into obscurity. Today, a number of orders of knighthood continue to exist in several countries, such as the English Order of the Garter, the Swedish Royal Order of the Seraphim, and the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav. Each of these orders has its own criteria for eligibility, but knighthood is generally granted by a head of state to selected persons to recognize some meritorious achievement. In the Legion of Honor, democracy became a part of the new chivalry. No longer was this limited to men of noble birth, as in the past, who received favors from their king. -

Constituent Councils May Confer Upon Any Member Who Has Not Held Or Is Not Presently Holding an Elected Office, “For Exception

A Constituent Council may confer upon any member who has not held or is not presently holding an elected office, “for exceptional service to the Council”, the rank of “Man-at Arms” of the Royal Order of the Red Branch of Eri. (RBE). The Council may do this at any time during the year. It becomes official upon notification to the AMD Grand Secretary and payment of the Passing Fee, either by the designee or by the Council. The Passing Fee is $25 for which the Council will receive the Certificate and lapel pin to be presented to the awardee. A Constituent Council may each year elect two brothers currently holding office in a Subordinate Council for the rank of “Esquire” of the Royal Order of the Red Branch of Eri. The Council may do this at any time during the year. It becomes official upon notification to the AMD Grand Secretary and payment of the Passing Fee, either by the designee or by the Council. The Passing Fee is $50 for which the Council will receive the Certificate, lapel pin, and blue collar & Jewel to be presented to the awardee. A Constituent Council may each year elect one Brother for the award of “Knight” of the Royal Order of the Red Branch of Eri. This Brother must have been a member of the Allied Masonic Degrees for a minimum of seven years. The Council may do this at any time during the year. It becomes official upon notification to the AMD Grand Secretary and payment of the Passing Fee, either by the designee or by the Council. -

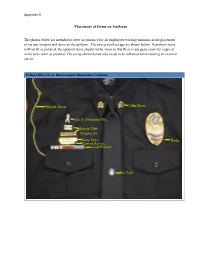

Placement of Items on Uniform

Appendix G Placement of Items on Uniform The photos below are intended to serve as guidance for all employees wearing uniforms in the placement of various insignia and items on the uniform. The two general set ups are shown below. If uniform items will not fit as pictured, the optional items should not be worn so that there is adequate room for required items to be worn as pictured. The set up shown below also needs to be followed when wearing an external carrier. Police Officer/Law Enforcement Dispatcher Uniform Whistle Chain Collar Brass Flag or Awareness Pin Special Unit Insignia (s) Name Plate Badge Years of Service Award Ribbons Tie Tack Appendix G Security Officer Uniform Collar Brass Whistle Chain Flag or Awareness Pin Special Unit Insignia (S) Name Plate Badge Years of Service Award Ribbons Tie Tack Appendix G Multiple Awards Devices Valor Merit Lifesaving Excellent Community Award Ribbon w/star Ribbon w/star Ribbon Ribbon Ribbon 1st w/cross w/number w/shield Award Two Stars Two Stars Two Crosses #2 #2 2nd Award One Big Star One Big Star Three Crosses #3 #3 3rd Award Four Crosses #4 #4 4th Award 1 Cross w/blue #5 #5 5th boarder Award #6 #6 6th Award #7 #7 7th Award #8 #8 8th Award #9 #9 9th Award #10 #10 10th - 14th Award +15th Award Appendix G Award Ribbon Order of Precedence Meritorious Service Award (2) Commendation for Valor (1) Community Service Commendation Excellent Service Award (4) Lifesaving Award (3) (5) Sample of Five Awards Five Awards – Situated above the right breast pocket, highest award is closest to the heart. -

The SS Collar

The Catholic Lawyer Volume 2 Number 2 Volume 2, April 1956, Number 2 Article 5 The SS Collar A. H. Ormerod Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/tcl Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Catholic Lawyer by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lawyers who are familiar with the SS collar as a badge of office of the Lord Chic Justice of England have wondered why it should be worn by Sir Thomas More who was once Lord Chancellor but never Chief Justice. We are indebted to A. H. Omerod, Esq., London, Eng- land for the following historical notes. THE SS COLLAR A. H. ORMEROD T HE HOLBEIN PORTRAIT of Sir Thomas More shows him wearing the collar of SS. The origin of this collar has"been a common puzzle to antiquaries, and one of the mysteries is why Sir Thomas More is wearing it. It is familiar to all lawyers in England as on state occasions it is worn over his judicial robes by the Lord Chief Justice of England. He wears it as successor of the Chief Justices of the Common Law Courts. In its present form it is a chain of gold composed of 26 knots and 27 letters of S linked together alternately. In the centre there is a Tudor rose attached on either side to a portcullis, the rose and portcullis being slightly larger than the other links. -

The Order of the Collar and the Other Institutions Belonging to the Royal House of Aragon, Majorca and Sicily the Royal House Of

MOC http://www.mocterranordica.org/eng/moc1.html The Order of the Collar and the other institutions belonging to the Royal House of Aragon, Majorca and Sicily The Royal House of Aragon, Majorca an Sicily has a number of orders in its patrimony. The most important of these is the Military Order of the Collar of Saint Agatha of Paternò. The other orders are largely honorific. There is also a college of arms and the Royal Majorcan Academy. Militare Ordine del Collare di Sant'Agata dei Paternò The Military Order of the Collar (MOC) was founded by King Alfonso III of Aragon on the 23rd January 1289 as a knightly institution with the purpose of defending Minorca. The member knights were obliged to live in the Fortress of Saint Agatha, situated in the region of Saint Agatha, and so became knows as “the knights from Saint Agatha”. They were each allocated a plot of land sufficient to maintain them in arms with a horse (“cavalleria”). The cavallerias were still active in the year 1600 and some are claimed to have survived into the 19th century. When don Ignazio, Prince of Biscari, travelled to the Balearics in the mid 18th century the remaining descendants told him of this ancient chivalric institution known as “the knights from Saint Agatha”. His notes were found by the seventh Duke of Carcaci who published them in his book in 1849. Much of the historic research has been made possible by the findings of Professor Elena Lourie in her article “La colonización cristiana de Menorca durante el Reinado de Alfonso III ‘El Liberal’ , rey de Aragón” in “Crusade and Colonisation” (ISBN 0-86078-266-2). -

The Livery Collar: Politics and Identity in Fifteenth-Century England

Ward, Matthew (2014) The livery collar: politics and identity in fifteenth-century England. PhD thesis, University of Nottingham. Access from the University of Nottingham repository: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/28022/1/629461.pdf Copyright and reuse: The Nottingham ePrints service makes this work by researchers of the University of Nottingham available open access under the following conditions. · Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. · To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in Nottingham ePrints has been checked for eligibility before being made available. · Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not- for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. · Quotations or similar reproductions must be sufficiently acknowledged. Please see our full end user licence at: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/end_user_agreement.pdf A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the repository url above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information, please contact -

The Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, in Ceremonies Often Referred to in the Itineraries of Pilgrims

The Knights of The Holy See Alessandra Malesci Baccani Department of Protocol Presidency of the Council of Ministries Office of the Knighthood of Honours and Heraldic The first Crusade took place between 1096–1099 and was ordered by Pope Urban II The Four Commanders were: Godfrey of Bouillon, Raimondo IV of Tolosa, Bohemond I of Antioch and Tancred of Altavilla 2 The Orders of Knighthoods of The Holy See Since Medieval times, The Church has maintained and supported and recognized military and religious Orders and over the years have established new Honoured Orders, or Knighthoods. The first title of The Equestrian Knight Pontiff; The Spur of Gold, is, to this day, still considered one of the most distinguished recognitions of honour. In 1471 The Pontiff Paul II awarded the first investiture “The Knights of Saint Peter” as an honoured title of The Holy See. The Knights of Saint Peter refers to the honoured investiture Knighthood of the Holy See., This Spur of Gold, is not to be confused with The Spur of Gold awarded by The Royal Cavalry Until 1500, at The Papal Court, there was not a real defined Equestrian Order, with privilege and duties established by regulation, in fact the investiture didn’t always have an official mantle and insignia. In 1520 the Pontiff Leone X founded The Order of Saint Peter, the first Honorary Institute of The Order of Saint Peter. Made up of 401 knights of various parts of The Apostolic Chancellery. The Title of Honour consisted of a medal. The Knights offered sums of money to The Holy See, and in exchange they received honours and income. -

Texas Numismatic Association

The TNA News Vol. 53 No. 2 Serving the Numismatic Community of Texas mar/aprmar/apr 2011 Numismatic treasures From the republic oF texas Texas NumismaTics ON Display aT TwO VeNues SMU DeGolyer Library Displays Houston Museum of Natural Science John Rowe III Currency Collection presents Texas! The Exhibition he John N. Rowe III Collection of Texas Currency at the Exhibit Includes Rare, Exquisite DeGolyer Library is the most comprehensive in the United Pieces of Early Texas Money TStates, representing thousands of notes, scrip, bonds, and other financial obligations, issued in Texas between the 1820s and 1935. everal years ago, former TNA President Jim Bevill embarked John Rowe, who has been collecting notes all his life, gave the on a journey to bring the world of Texas numismatics into the collection to SMU in 2003, so that it would be preserved and made Smainstream study of Texas history. Although he originally accessible to others. This digital collection includes currency from planned an exhibit of Republic of Texas money at the Alamo, significant historical eras, including the Republic of Texas (1836- delays in fund raising for the potential exhibit space on the Alamo 1845), early statehood (1845-1861), the Confederacy (1861-1865), grounds never materialized, and the long anticipated numismatic and the National Bank Era (1863-1913). exhibit was temporarily shelved. The Rowe currency collection offers an interesting avenue of access In the process, he began to life in Texas from the early days of its independence from Mexico writing a book on the through the years of the Great Depression. -

The London Gazette, 2 June, 1936 3517

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 2 JUNE, 1936 3517 ordained that men and women admitted to Cross or Honorary Dame 'Grand 'Cross who this Order shall take rank among themselves shall not have received a Collar of this Order. according to the dates of their respective XII. It is ordained that all Knights Grand nominations in the Classes of the Order to Cross and Dames Grand /Cross who have which they severally belong. received, or shall receive, Collars of this Order VIII. It is ordained that the Insignia and shall make arrangements for their return to Robes of the Sovereign of this Order shall be the Chancery of the Order in the event of the of the same material and fashion as are herein-, said Knights or Dames receiving Collars of an' after appointed for the Knights Grand Cross, Order of higher rank and precedence, or of save only with those alterations which distin- their decease. And it is ordained that a guish Our Royal Dignity. Foreign Ambassador, or Foreign Minister, to IX. It is ordained that the Knights Gran'd the Court of 'Saint. James's, on whom has been, Cross and Dames 'Grand Cross of this Order or shall be, conferred the dignity of an shall upon all great and solemn occasions wear Honorary Knight Grand Cross of this Order, the Badge of the Order, which shall consist and who has received, or shall receive, the of a white enamelled Maltese Cross of eight Collar of the Order, shall .return the said points, .on an oval centre of crimson enamel Collar to the Chancery of the Order on his the Royal and Imperial Monogram of Our recall to his own country. -

ELLEN S. PODGOR Gary R. Trombley Family White-Collar Research

ELLEN S. PODGOR Gary R. Trombley Family White-Collar Research Professor & Professor of Law Stetson University College of Law 1401 61st Street South Gulfport, Florida 33707 727-562-7348 404-915-0800 (cell) [email protected] EDUCATION: Graduate Law: Temple University School of Law (LL.M.) Graduate Business: University of Chicago (M.B.A.) Law: Indiana University School of Law at Indianapolis (J.D.) Associate Editor - Indiana Law Review Undergraduate: Syracuse University (B.S. Magna Cum Laude) SIGNIFICANT EMPLOYMENT & SABBATICAL INFORMATION: 8/2006- Present Stetson University College of Law - Professor of Law (tenured) Inaugural Associate Dean of Faculty Development & Electronic Education (8/2006-8/2009) Gary R. Trombley Family White-Collar Crime Research Professor (2/2011- present) L. Leroy Highbaugh Sr. Research Chair (8/2010 -2/2011) Visiting Culverhouse Chair (Fall 2005, Spring 2006) Courses: C Criminal Law C White Collar Crime C Criminal Procedure: Adjudication C White Collar Advocacy C International Criminal Law (also taught as a web based synchronous distance learning course to displaced Katrina students from Loyola University Law School- New Orleans) C Law & Sexual Orientation (co-taught) C Supreme Court Advocacy & Process C Nelson Mandela & International Human Rights (Capetown Summer Program - 2018) C Introduction to International Criminal Law (Hague Summer Program - 2009) C Federal Criminal Law C Diverse Issues in Advocacy (co-taught) C United States Legal Systems (LL.M. Class) C Clemency (co-taught with Federal Defender)