The State of Human Rights in the Protracted Conflict in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE to SOUTH SUDAN Last Updated 07/31/13

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO SOUTH SUDAN Last Updated 07/31/13 UPPER NILE SUDAN WARRAP ACTED Solidarités ACTED CRS World ABYEI AREA Renk Vision GOAL Food for SOUTH SUDAN CRS SC the Hungry ACTED MENTOR UNITY FAO UNDP GOAL DRC NRC CARE Global Communities/CHF UNFPA Medair IOM UNOPS Mercy Corps GOAL UNICEF MENTOR RI WCDO MENTOR Mercy Corps UNMAS RI World IOM Paloich OCHA WHO Vision SouthSouth Sudan-SudanSudan-Sudan boundaryboundary representsrepresents JanuaryJanuary 1,1, 19561956 alignment;alignment; finalfinal alignmentalignment pendingpending ABYEI AREA * UPPER NILE negotiationsnegotiations andand demarcation.demarcation. Abyei ETHIOPIA Malakal Abanima SOUTH SUDAN-WIDE Bentiu Nagdiar Warawar JONGLEI FAO Agok Yargot ACTED IOM WESTERN BAHR Malualkon NORTHERN UNITY EL GHAZAL Aweil Khorflus Nasir CRS Medair BAHR Pagak WARRAP Food for OCHA Raja EL GHAZAL the Hungry UNICEF Fathay Walgak BAHR EL GHAZAL IMC Akobo WFP Adeso MENTOR Wau WHO Tearfund PACT SOUTH SUDAN JONGLEI UNICEF UMCOR Pochalla World WFP Vision Welthungerhilfe Rumbek ICRC LAKES UNHCR CENTRAL Wulu Mapuordit AFRICAN Akot Bor Domoloto Minkamman REPUBLIC PROGRAM KEY Tambura Amadi USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM Kaltok WESTERN EQUATORIA EASTERN EQUATORIA Agriculture and Food Security Livelihoods Juba Kapoeta Economic Recovery and Market Logistics and Relief Commodities Systems Yambio Multi-Sectoral Assistance CENTRAL Education EQUATORIA Torit Nagishot Nutrition EQUATORIA Gender-based Birisi ARC Violence Prevention Protection Ye i CHF Health Risk Management Policy and Practice KENYA -

Cholera in South Sudan Situation Report # 95 As at 23:59 Hours, 29 September to 5 October 2014

Republic of South Sudan Cholera in South Sudan Situation Report # 95 as at 23:59 Hours, 29 September to 5 October 2014 Situation Update As of 5 October 2014, a total of 6,139 cholera cases including 139 deaths (CFR 2%) had been reportedTable 1. Summary in South of Suda choleran as cases summarizedreported in in Juba Tables County 1 and, 23 2.April – 5 October 2014 New New New deaths Total cases Total Total admisions discharges Total Total cases Reporting Sites 29 Sept to currently facility community Total cases 29 Sept to 29 Sept to deaths discharged 5 Oct 2014 admitted deaths deaths 5 Oct 2014 5 Oct 2014 JTH CTC 0 0 0 0 16 0 16 1466 1482 Gurei CTC (changed to ORP) Closed 28 July 2 0 2 365 367 Tongping CTC 0 2 1 3 69 72 Closed August Jube 3/UN House CTC Closed August 0 0 0 0 97 97 Nyakuron West CTC Closed 15 July 0 0 0 18 18 Gumbo CTC Closed 5 July 0 0 0 48 48 Nyakuron ORP Closed 5 July 0 0 0 20 20 Munuki ORP Closed 5 July 0 0 0 8 8 Gumbo ORP Closed 15 July 0 3 3 67 70 Pager PHCU 0 0 0 0 1 5 6 42 48 Other sites 0 0 0 1 15 16 1 17 Total 0 0 0 0 22 24 46 2201 2247 N.B. To prevent double counting of patients, transferred cases from ORPs to CTCs are not counted in the ORPs. Table 2: Summary of cholera cases reported outside Juba County, 23 April – 5 October 2014 New New New Total cases Total Total admisions discharges deaths Total Total cases Total States Reporting Sites currently facility community 29 Sept to 29 Sept to 29 Sep to deaths discharged cases admitted deaths deaths 5 Oct 2014 5 Oct 2014 5 Oct 14 Kajo-Keji civil hospital 0 0 0 0 -

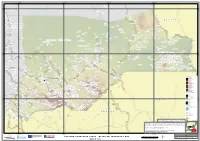

Ss 9303 Ee Kapoeta North Cou

SOUTH SUDAN Kapoeta North County reference map SUDAN Pibor JONGLEI ETHIOPIA CAR DRC KENYA UGANDA EASTERN EQUATORIA Kenyi Lafon Kapoeta East Akitukomoi Kangitabok Lomokori Kapoeta North Ngigalingatun Kangibun Kalopedet Lokidangoai Nomogonjet Nawitapal Mogos Chokagiling Lorutuk Lokoges Nakwa Owetiani Nawabei Natatur Kamaliato Kanyowokol Karibungura Lokale Nagira Belengtobok Tuliabok Lokorechoke Kadapangolol Akoribok Nakwaparich Kalobeliang Wana Kachinga Lomus Lotiakara Pucwa Lopetet Nawao Lokorilam Naduket Tingayta Lodomei Kibak Nakatiti International boundary Nakapangiteng Napusiret Napulak State boundary Loriwo County boundary Kochoto Naminitotit Parpar Undetermined boundary Napusireit Nakwamoru Abyei region Kotak Kasotongor Napochorege Katiakin Nawayareng Riwoto Lokorumor Country capital Nangoletire Lokualem Lumeyen Logerain Lomidila Takankim Lobei Administrative centre/County capital Lokwamor Nacukut Naronyi Nakoret Lotiekar Namukeris Principal town Napotit Naoyatir Nakore Napureit Secondary town Lokwamiro Narubui Barach Lolepon Lotiri Paima Village Loregai Narongyet Lochuloit Kabuni Primary road Kudule Locheler Napusiria Napotpot Secondary road Nacholobo Tertiary road Budi Idong Main river Kapoeta South 0 5 10 km The administrative boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. Final status of Abyei area is not yet determined. Created: March 2020 | Code: SS-9303 | Sources: OCHA, SSNBS | Feedback: [email protected] | unocha.org/south-sudan | reliefweb.int/country/ssd | southsudan.humanitarianresponse.info . -

Cholera in South Sudan Situation Report # 67 As at 23:59 Hours, 22 July 2014 Situation Update

Republic of South Sudan Cholera in South Sudan Situation Report # 67 as at 23:59 Hours, 22 July 2014 Situation Update As of 22 July 2014, a total of 4,765 cholera cases including 109 deaths (CFR 2.3%) had been reported in South Sudan as summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Laboratory results have confirmed cholera cases in Kapoeta North and Budi counties in Eastern Equatoria state. Table 1. Summary of cholera cases reported in Juba County, 23 April - 22 July 2014 New New Total cases Total Total New deaths Total Total cases Reporting Sites admisions discharges currently facility community Total cases today deaths discharged today today admitted deaths deaths JTH CTC 3 9 0 2 16 0 16 1393 1411 Gurei CTC (changed to ORP) 3 3 0 0 2 0 2 363 365 Tongping CTC 0 0 0 3 2 1 3 58 64 Jube 3/UN House CTC 5 5 0 9 0 0 0 57 66 Nyakuron West CTC Closed 15 July 0 0 0 18 18 Gumbo CTC Closed 5 July 0 0 0 48 48 Nyakuron ORP Closed 5 July 0 0 0 20 20 Munuki ORP Closed 5 July 0 0 0 8 8 Gumbo ORP Closed 15 July 0 3 3 67 70 Other sites 0 0 0 0 1 14 15 1 16 Total 11 17 0 14 21 18 39 2033 2086 N.B. To prevent double counting of patients, transferred cases from ORPs to CTCs are not counted in the ORPs. Table 2. Summary of cholera cases reported outside Juba County, 23 April – 22 July 2014 New New New Total cases Total Total Total Total cases Total States Reporting Sites admisions discharges deaths currently facility community deaths discharged cases today today today admitted deaths deaths Kajo-Keji civil hospital X X X 2 1 2 3 53 59 CES Yei Hospital X X X 0 0 2 2 45 47 -

1 Covid-19 Weekly Situation

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN MINISTRY OF HEALTH (MOH) PUBLIC HEALTHPUBLIC EMERGENCY HEALTH EMERGENCY OPERATIONS OPERATIONS CENTRE (PHEOC) CENTRE (PHEOC) COVID-19 WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT Issue NO: 33 Reporting Period: 12-18 October 2020 (week 42) 36,740 2,655 CUMULATIVE SAMPLES TESTED CUMULATIVE RECOVERIES 2,847 CUMULATIVE CONFIRMED CASES 55 9,152 CUMULATIVE DEATHS CUMULATIVE CONTACTS LISTED FOR FOLLOW UP 1. KEY HIGHLIGHTS A cumulative total of 2,847 cases have been confirmed and 55 deaths have been recorded, with case fatality rate (CFR) of 1.9 percent including 196 imported cases as of 18 October 2020. 1 case is currently isolated in health facilities in the Country; and the National IDU has 99% percent bed occupancy available. 2,655 cases (0 new) have been discharged to date. 135 Health Care Workers have been infected since the beginning of the outbreak, with one death. 9,152cumulative contacts have been registered, of which 8,835 have completed the 14-day quarantine. Currently, 317 contacts are being followed, of these 92.1 percent (n=292) contacts were reached. 722 contacts have converted to cases to date; accounting for 25.3 percent of all confirmed cases. Cumulatively 36,740 laboratory tests have been performed with 7.7 percent positivity rate. There is cumulative total of 1,373 alerts of which 86.5 percent (n=1, 187) have been verified and sampled; Most alerts have come from Central Equatorial State (75.1 percent), Eastern Equatoria State (4.4 percent); Upper Nile State (3.2 percent) and the remaining 17.3 percent are from the other States and Administrative Areas. -

Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014

IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment: Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014 This IRNA Report is a product of Inter-Agency Assessment mission conducted and information compiled based on the inputs provided by partners on the ground including; government authorities, affected communities/IDPs and agencies. 0 IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Situation Overview: An ad-hoc IDP camp has been established by the Melut County Commissioner at Dethoma in order to accommodate Dinka IDPs who have fled from Baliet county. Reports of up to 45,000 based in Paloich were initially received by OCHA from RRC and UNMISS staff based in Melut but then subsequent information was received that they had moved to Dethoma. An IRNA mission from Malakal was conducted on 31 January 2014. Due to delays in the deployment by helicopter, the RRC Coordinator was unable to meet the team but we were able to speak to the Deputy Paramount Chief, Chief and a ROSS NGO at the site. The local NGO (Woman Empowerment for Cooperation and Development) had said they had conducted a preliminary registration that showed the presence of 3,075 households. The community leaders said that the camp contained approximately 26,000 individuals. The IRNA team could only visually estimate 5 – 6000 potentially displaced however some may have been absent at the river. The camp is situated on an open field provided and cleared by the Melut County Commissioner, with a river approximately 300metres to the south. There is no cover and as most IDPs had walked to this location, they had carried very minimal NFIs or food. -

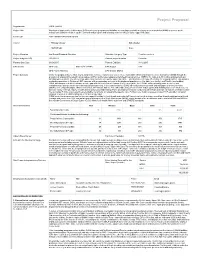

Project Proposal

Project Proposal Organization GOAL (GOAL) Project Title Provision of treatment to children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women diagnosed with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) or severe acute malnutrition (SAM) for children aged 659 month and pregnant and lactating women in Melut County, Upper Nile State Fund Code SSD15/HSS10/SA2/N/INGO/526 Cluster Primary cluster Sub cluster NUTRITION None Project Allocation 2nd Round Standard Allocation Allocation Category Type Frontline services Project budget in US$ 150,000.01 Planned project duration 5 months Planned Start Date 01/08/2015 Planned End Date 31/12/2015 OPS Details OPS Code SSD15/H/73049/R OPS Budget 0.00 OPS Project Ranking OPS Gender Marker Project Summary Under the proposed intervention, GOAL will provide curative responses to severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) through the provision of outpatient therapeutic programmes (OTPs) and targeted supplementary feeding programmes (TSFPs) for children 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW). The intervention will be targeted to Melut County, Upper Nile State – which has been heavily affected by the ongoing conflict. This includes continuing operations in Dethoma II IDP camp as well as expanding services to the displaced populations in Kor Adar (one facility) and Paloich (two facilities). GOAL also proposes to fill the nutrition service gap in Melut Protection of Civilians (PoC) camp. In the PoC, GOAL will be providing static services, with complementary primary health care and nutrition programming. In the same locations, GOAL will conduct mass outreach and mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening campaigns within communities, IDP camps, and the PoC with children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW) in order to increase facility referrals. -

AREA-BASED ASSESSMENT in AREAS of RETURN OCTOBER 2019 Renk Town, Renk County, Upper Nile State, South Sudan

AREA-BASED ASSESSMENT IN AREAS OF RETURN OCTOBER 2019 Renk Town, Renk County, Upper Nile State, South Sudan CONTEXT ASSESSED LOCATION Renk Town is located in Renk County, Upper Nile State, near South Sudan’s border SUDAN Girbanat with Sudan. Since the formation of South Sudan in 2011, Renk Town has been a major Gerger ± MANYO Renk transit point for returnees from Sudan and, since the beginning of the current conflict in Wadakona 1 2013, for internally displaced people (IDPs) fleeing conflict in Upper Nile State. RENK Renk was classified by the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) Analysis Workshop El-Galhak Kurdit Umm Brabit in August 2019 as Phase 4 ‘Emergency’ with 50% of the population in either Phase 3 Nyik Marabat II 2 Kaka ‘Crisis’ (65,997 individuals) or Phase ‘4’ Emergency’ (28,284 individuals). Additionally, MELUT Renk was classified as Phase 5 ‘Extremely Critical’ for Global Acute Malnutrition MABAN (GAM),3 suggesting the prevalence of acute malnutrition was above the World Health Kumchuer Organisation (WHO) recommended emergency threshold with a recent REACH Multi- Suraya Hai Sector Needs Assessment (MSNA) establishing a GAM of above 30%.4 A measles Soma outbreak was declared in June 2019 and access to clean water was reportedly limited, as flagged by the Needs Analysis Working Group (NAWG) and by international NGOs 4 working on the ground. Hai Marabat I Based on the convergence of these factors causing high levels of humanitarian Emtitad Jedit Musefin need and the possibility for larger-scale returns coming to Renk County from Sudan, REACH conducted this Area-Based Assessment (ABA) in order to better understand White Hai Shati the humanitarian conditions in, and population movement dynamics to and from, Renk N e l Town. -

World Vision South Sudan ECHO FOOD VOUCHER RAPID ASSESSMENT REPORT

1 | P a g e World Vision South Sudan ECHO FOOD VOUCHER RAPID ASSESSMENT REPORT JUNE 2014 By: Bernard D. Togba Jr. Francis Thomas Mogga World Vision South Sudan 2 | P a g e Table of Contents Topic Page List of Tables……………………………………………………………………….………………….. 3 List of Acronyms……………………………………………………………………………………… 4 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………..……………… 5 2. Objectives……………………………………………………………………………….…………. 6 3. Methodology……………………………………………………………………………….………. 6 3.1. Sample………………………………………………………………………………………….7 3.2. Data Management & Analysis………………………………………………………………….. 7 3.3. Limitations……………………………………………………………………………………… 7 4. Overview of Towns…………………………………………………………………………………. 8 4.1. Overview of Malakal…………………………………………………………………………… 8 4.2. Overview of Renk………………………………………………………………………………. 8 4.3. Overview of Kodok…………………………………………………………………………….. 10 4.4. Overview of Lul……………………………………………………………………………….. 10 4.5. Food Availability……………..…………………………………………………………………. 11 5. Summary Results………………………………………………………………………………………11 5.1. Key Informants……………………..……………………………………………………………..11 5.2. Traders…………………………………………………………………………………………….12 5.2.1. Business & Supply………………………………………………………………………. 13 5.2.2. Payment & Transport…………………………….……………………………………. 17 5.3. Beneficiaries………………………………………………………..…………………………….. 19 5.3.1. IDPs Perception…………………………….……..…………………………………… 19 5.3.2. General Characteristics………………………………………………………………….19 5.3.3. Household Welfare & Vulnerability………………………………..…………………… 19 6. Conclusions…………………………………………………………………………………………… 22 World Vision South Sudan 3 | P -

LC SS 706 A1 EEQ 20130301.Pdf

pp p ! ! p ! p (! ! !( 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E Gwalla Awan KolnyangAluk Katanich Titong Munini Beru ! R . K Wowa ang en Logoda N Rigl Chilimun N " " 0 0 p' Bor South County ' 0 Pibor County Lowelli Katchikan River Bellel Kichepo 0 ° Maktiweng J O N G L E I ° 6 Kaigo 6 Lochiret R. Naro Kenamuke Swamp R Ngechele . S Neria u p Kanopir Natibok Kabalatigo i r i ( B Moru Kimod a Rongada h r Yebisak e g l- n Tombi J o e b b l Shogle e a l) Buka h C . Gwojo-Adung Kassangor R Baro ! E T H I O P I A Moru Kerri KURON Kuron Gigging p Bojo-Ajut Gemmaiza ! Karn Ethi Kerkeng Moru Ethi Nakadocwa Poko Wani Terekeka County Kobowen Swamp Borichadi Bokuna Poko Kassengo Selemani Pagar Nabwel Wani Mika Chabong Tukara C E N T R A L p River Nakua p Kenyi E Q U A T O R I A Moru Angbin Mukajo Gali Owiyabong Kursomba Lotimor Bulu Koli Kalaruz Awakot Katima Waha ! Akitukomoi River Gera Tumu Nanyangachor Nyabongi Napalap ! Namoropus Natilup Swamp ) it Wanyang Kangitabok Lomokori le Eyata Moru Kolinyagkopil il ! Terakeka ri Lozut Lomongole t iti o (! S L Magara p R. ( n Umm Gura Mwanyakapin a p y l Abuilingakine Lomareng Plateau a Dogora R Ngigalingatun k o . L Jelli L o p Rambo Djie Navi . Lokodopotok Nyaginei Kangeleng p R Biyara Nai A o Kworijik Kangibun Lomuleye Katirima t o Simsima Badigeru Swamp River Lokuja Losagam k Musha Lukwatuk Pass Doinyoro East p o p l Balala Legeri Buboli Kalopedet Pongo River Lokorowa Watha Peth Hills Bume E A S T E R N E Q U A T O R I A Lokidangoai Nawitapal Lopokori Lokomarukest Kolobeleng Yakara Dogatwan Nomogonjet Kagethi ! Mogos Bala Pool Lapon County Lotakawa Kanyabu Moru Ethi Donyiro West Donyiro Cliff Kedowa Kothokan a l l i Chokagiling t Karakamuge o Mangalla Bwoda L Mediket Kaliapus Nyangatom !( . -

Final Report

THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Rural Development, Upper Nile State THE PROJECT FOR COMPREHENSIVE PLANNING AND SUPPORT FOR URGENT DEVELOPMENT ON SOCIAL ECONOMIC INFRASTRUCTURE IN MALAKAL TOWN IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN FINAL REPORT MAIN TEXT JULY 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD. EI RECS INTERNATIONAL INC. JR KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., LTD. 14-122 The Project for Comprehensive Planning and Support for Urgent Development on Social Economic Infrastructure in Malakal Town in the Republic of South Sudan Project Area Malakal Air Port ✈ Outer Ring Road Ring Road Ring Nile River Nile LBT Road-1 M al ak al Ri ve LB r T Po Ro ad- MoPI&RD 3 LBT Road-1 LEGEND: :Block Boundary :Road :River :Forest :Grassland :Idle Land (Sand and Mud) :Shrub Urgnt Development Support Projects :Water Treatment Plant :Water Pipe :Water Public Tab :Malakal Port :LBT Road PROJECT LOCATION MAP Final Report The Project for Comprehensive Planning and Support for Urgent Development on Social Economic Infrastructure in Malakal Town in the Republic of South Sudan Photographs Present Situation of Socio-Economic Infrastructure in Malakal Town 1 Water Treatment Plant of SSUWC Water pipes are detariorated and damaged, (Filter Tank) resulting in high ratio of non-revenue water Malakal Port (Cargo Jetty) Malakal Port (Passenger Jetty) Community Road (Black and Clayey Soil Community roads easily get muddy in rainy called Black Cotton Soil) season. LBT Construction Site (Upper -

Viable Support to Transition and Stability (Vistas) Fy 2016 Annual Report October1, 2015 - September 30, 2016

VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) FY 2016 ANNUAL REPORT OCTOBER1, 2015 - SEPTEMBER 30, 2016 JUNE 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by AECOM. VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) FY 2016 ANNUAL REPORT OCTOBER 1, 2015- SEPTEMBER 30, 2016 Contract No. AID-668-C-13-00004 Submitted to: USAID South Sudan Prepared by: AECOM International Development Prepared for: Office of Transition and Conflict Mitigation (OTCM) USAID South Sudan Mission American Embassy Juba, South Sudan DISCLAIMER: The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. FY 2016 Annual Report/ Viable Support to Transition and Stability (VISTAS) i TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 II. Political and security Landscape ............................................................................................ 2 National Political, Security, and Operational Landscape ........................................................................... 2 Political & Security Landscape in VISTAS Regional Offices ...................................................................... 4 III. Program Strategy.................................................................................................................... 7 IV. Program Highlights