A Special Issue in Memory of George B. Dantzig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6799/positional-notation-or-trigonometry-2-13-106799.webp)

Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]

The Greatest Mathematical Discovery? David H. Bailey∗ Jonathan M. Borweiny April 24, 2011 1 Introduction Question: What mathematical discovery more than 1500 years ago: • Is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, single discovery in the field of mathematics? • Involved three subtle ideas that eluded the greatest minds of antiquity, even geniuses such as Archimedes? • Was fiercely resisted in Europe for hundreds of years after its discovery? • Even today, in historical treatments of mathematics, is often dismissed with scant mention, or else is ascribed to the wrong source? Answer: Our modern system of positional decimal notation with zero, to- gether with the basic arithmetic computational schemes, which were discov- ered in India prior to 500 CE. ∗Bailey: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Email: [email protected]. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Computational and Technology Research, Division of Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. yCentre for Computer Assisted Research Mathematics and its Applications (CARMA), University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 1 2 Why? As the 19th century mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace explained: It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit. But its very sim- plicity and the great ease which it has lent to all computations put our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions; and we shall appre- ciate the grandeur of this achievement the more when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest men produced by antiquity. -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

Curriculum Vitæ

Aleksandr M. Kazachkov May 30, 2021 Contact Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering Website akazachk.github.io Information Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering Email akazachkov@ufl.edu 303 Weil Hall, P.O. Box 116595 Office 401B Weil Hall Gainesville, FL 32611-6595, USA Phone +1.352.273.4902 Research Discrete optimization, including theoretical, methodological, and applied aspects, with an emphasis on devel- Interests oping better cutting plane techniques and open-source computational contributions Computational economics, particularly on the fair allocation of indivisible resources and fair mechanism design Social good applications, such as humanitarian logistics and donation distribution Academic University of Florida, Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, Gainesville, FL, USA Positions Assistant Professor January 2021 – Present Courtesy Assistant Professor March 2020 – December 2020 Polytechnique Montréal, Department of Mathematics and Industrial Engineering, Montréal, QC, Canada Postdoctoral Researcher under Andrea Lodi May 2018 – December 2020 Education Carnegie Mellon University, Tepper School of Business, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Ph.D. in Algorithms, Combinatorics, and Optimization under Egon Balas May 2018 Dissertation: Non-Recursive Cut Generation M.S. in Algorithms, Combinatorics, and Optimization May 2013 Cornell University, College of Engineering, Ithaca, NY, USA B.S. in Operations Research and Engineering with Honors, Magna Cum Laude May 2011 Publications [1] P.I. Frazier and A.M. Kazachkov. “Guessing Preferences: A New Approach to Multi-Attribute Ranking and Selection”, Winter Simulation Conference, 2011. [2] J. Karp, A.M. Kazachkov, and A.D. Procaccia. “Envy-Free Division of Sellable Goods”, AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2014. [3] J.P. Dickerson, A.M. Kazachkov, A.D. Procaccia, and T. -

Algorithmic System Design Under Consideration of Dynamic Processes

Algorithmic System Design under Consideration of Dynamic Processes Vom Fachbereich Maschinenbau an der Technischen Universit¨atDarmstadt zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Ingenieurwissenschaften (Dr.-Ing.) genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Dipl.-Phys. Lena Charlotte Altherr aus Karlsruhe Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Peter F. Pelz Mitberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Ulf Lorenz Tag der Einreichung: 19.04.2016 Tag der m¨undlichen Pr¨ufung: 24.05.2016 Darmstadt 2016 D 17 Vorwort des Herausgebers Kontext Die Produkt- und Systementwicklung hat die Aufgabe technische Systeme so zu gestalten, dass eine gewünschte Systemfunktion erfüllt wird. Mögliche System- funktionen sind z.B. Schwingungen zu dämpfen, Wasser in einem Siedlungsgebiet zu verteilen oder die Kühlung eines Rechenzentrums. Wir Ingenieure reduzieren dabei die Komplexität eines Systems, indem wir dieses gedanklich in überschaubare Baugruppen oder Komponenten zerlegen und diese für sich in Robustheit und Effizienz verbessern. In der Kriegsführung wurde dieses Prinzip bereits 500 v. Chr. als „Teile und herrsche Prinzip“ durch Meister Sun in seinem Buch „Die Kunst der Kriegsführung“ beschrieben. Das Denken in Schnitten ist wesentlich für das Verständnis von Systemen: „Das wichtigste Werkzeug des Ingenieurs ist die Schere“. Das Zusammenwirken der Komponenten führt anschließend zu der gewünschten Systemfunktion. Während die Funktion eines technischen Systems i.d.R. nicht verhan- delbar ist, ist jedoch verhandelbar mit welchem Aufwand diese erfüllt wird und mit welcher Verfügbarkeit sie gewährleistet wird. Aufwand und Verfügbarkeit sind dabei gegensätzlich. Der Aufwand bemisst z.B. die Emission von Kohlendioxid, den Energieverbrauch, den Materialverbrauch, … die „total cost of ownership“. Die Verfügbarkeit bemisst die Ausfallzeiten, Lebensdauer oder Laufleistung. Die Gesell- schaft stellt sich zunehmend die Frage, wie eine Funktion bei minimalem Aufwand und maximaler Verfügbarkeit realisiert werden kann. -

54 OP08 Abstracts

54 OP08 Abstracts CP1 Dept. of Mathematics Improving Ultimate Convergence of An Aug- [email protected] mented Lagrangian Method Optimization methods that employ the classical Powell- CP1 Hestenes-Rockafellar Augmented Lagrangian are useful A Second-Derivative SQP Method for Noncon- tools for solving Nonlinear Programming problems. Their vex Optimization Problems with Inequality Con- reputation decreased in the last ten years due to the com- straints parative success of Interior-Point Newtonian algorithms, which are asymptotically faster. In the present research We consider a second-derivative 1 sequential quadratic a combination of both approaches is evaluated. The idea programming trust-region method for large-scale nonlin- is to produce a competitive method, being more robust ear non-convex optimization problems with inequality con- and efficient than its ”pure” counterparts for critical prob- straints. Trial steps are composed of two components; a lems. Moreover, an additional hybrid algorithm is defined, Cauchy globalization step and an SQP correction step. A in which the Interior Point method is replaced by the New- single linear artificial constraint is incorporated that en- tonian resolution of a KKT system identified by the Aug- sures non-accent in the SQP correction step, thus ”guiding” mented Lagrangian algorithm. the algorithm through areas of indefiniteness. A salient feature of our approach is feasibility of all subproblems. Ernesto G. Birgin IME-USP Daniel Robinson Department of Computer Science Oxford University [email protected] -

From the Collections of the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton, NJ

From the collections of the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton, NJ These documents can only be used for educational and research purposes (“Fair use”) as per U.S. Copyright law (text below). By accessing this file, all users agree that their use falls within fair use as defined by the copyright law. They further agree to request permission of the Princeton University Library (and pay any fees, if applicable) if they plan to publish, broadcast, or otherwise disseminate this material. This includes all forms of electronic distribution. Inquiries about this material can be directed to: Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library 65 Olden Street Princeton, NJ 08540 609-258-6345 609-258-3385 (fax) [email protected] U.S. Copyright law test The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or other reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or other reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. The Princeton Mathematics Community in the 1930s Transcript Number 11 (PMC11) © The Trustees of Princeton University, 1985 MERRILL FLOOD (with ALBERT TUCKER) This is an interview of Merrill Flood in San Francisco on 14 May 1984. The interviewer is Albert Tucker. -

The Book Review Column1 by William Gasarch Department of Computer Science University of Maryland at College Park College Park, MD, 20742 Email: [email protected]

The Book Review Column1 by William Gasarch Department of Computer Science University of Maryland at College Park College Park, MD, 20742 email: [email protected] In this column we review the following books. 1. We review four collections of papers by Donald Knuth. There is a large variety of types of papers in all four collections: long, short, published, unpublished, “serious” and “fun”, though the last two categories overlap quite a bit. The titles are self explanatory. (a) Selected Papers on Discrete Mathematics by Donald E. Knuth. Review by Daniel Apon. (b) Selected Papers on Design of Algorithms by Donald E. Knuth. Review by Daniel Apon (c) Selected Papers on Fun & Games by Donald E. Knuth. Review by William Gasarch. (d) Companion to the Papers of Donald Knuth by Donald E. Knuth. Review by William Gasarch. 2. We review jointly four books from the Bolyai Society of Math Studies. The books in this series are usually collections of article in combinatorics that arise from a conference or workshop. This is the case for the four we review. The articles here vary tremendously in terms of length and if they include proofs. Most of the articles are surveys, not original work. The joint review if by William Gasarch. (a) Horizons of Combinatorics (Conference on Combinatorics Edited by Ervin Gyori,¨ Gyula Katona, Laszl´ o´ Lovasz.´ (b) Building Bridges (In honor of Laszl´ o´ Lovasz’s´ 60th birthday-Vol 1) Edited by Martin Grotschel¨ and Gyula Katona. (c) Fete of Combinatorics and Computer Science (In honor of Laszl´ o´ Lovasz’s´ 60th birthday- Vol 2) Edited by Gyula Katona, Alexander Schrijver, and Tamas.´ (d) Erdos˝ Centennial (In honor of Paul Erdos’s˝ 100th birthday) Edited by Laszl´ o´ Lovasz,´ Imre Ruzsa, Vera Sos.´ 3. -

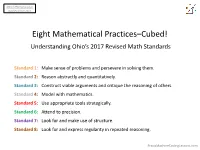

Eight Mathematical Practices–Cubed! Understanding Ohio’S 2017 Revised Math Standards

NWO STEM Symposium Bowling Green 2017 Eight Mathematical Practices–Cubed! Understanding Ohio’s 2017 Revised Math Standards Standard 1: Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. Standard 2: Reason abstractly and quantitatively. Standard 3: Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others. Standard 4: Model with mathematics. Standard 5: Use appropriate tools strategically. Standard 6: Attend to precision. Standard 7: Look for and make use of structure. Standard 8: Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning. PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Exploring What’s New in Ohio’s 2017 Revised Math Standards • No Revisions to Math Practice Standards. • Minor Revisions to Grade Level and/or Content Standards. • Revisions Clarify and/or Lighten Required Content. Drill-Down Some Old/New Comparisons… PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Clarify Kindergarten Counting: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Lighten Adding 5th Grade Fractions: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Lighten Solving High School Quadratics: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Ohio 2017 Math Practice Standard #1 1. Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. Mathematically proficient students start by explaining to themselves the meaning of a problem and looking for entry points to its solution. They analyze givens, constraints, relationships, and goals. They make conjectures about the form and meaning of the solution and plan a solution pathway rather than simply jumping into a solution attempt. They consider analogous problems, and try special cases and simpler forms of the original problem in order to gain insight into its solution. They monitor and evaluate their progress and change course if necessary. Older students might, depending on the context of the problem, transform algebraic expressions or change the viewing window on their graphing calculator to get the information they need. -

Federal Regulatory Management of the Automobile in the United States, 1966–1988

FEDERAL REGULATORY MANAGEMENT OF THE AUTOMOBILE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1966–1988 by LEE JARED VINSEL DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences of Carnegie Mellon University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Carnegie Mellon University May 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor David A. Hounshell, Chair Professor Jay Aronson Professor John Soluri Professor Joel A. Tarr Professor Steven Usselman (Georgia Tech) © 2011 Lee Jared Vinsel ii Dedication For the Vinsels, the McFaddens, and the Middletons and for Abigail, who held the ship steady iii Abstract Federal Regulatory Management of the Automobile in the United States, 1966–1988 by LEE JARED VINSEL Dissertation Director: Professor David A. Hounshell Throughout the 20th century, the automobile became the great American machine, a technological object that became inseparable from every level of American life and culture from the cycles of the national economy to the passions of teen dating, from the travails of labor struggles to the travels of “soccer moms.” Yet, the automobile brought with it multiple dimensions of risk: crashes mangled bodies, tailpipes spewed toxic exhausts, and engines “guzzled” increasingly limited fuel resources. During the 1960s and 1970s, the United States Federal government created institutions—primarily the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration within the Department of Transportation and the Office of Mobile Source Pollution Control in the Environmental Protection Agency—to regulate the automobile industry around three concerns, namely crash safety, fuel efficiency, and control of emissions. This dissertation examines the growth of state institutions to regulate these three concerns during the 1960s and 1970s through the 1980s when iv the state came under fire from new political forces and governmental bureaucracies experienced large cutbacks in budgets and staff. -

FOCUS August/September 2005

FOCUS August/September 2005 FOCUS is published by the Mathematical Association of America in January, February, March, April, May/June, FOCUS August/September, October, November, and Volume 25 Issue 6 December. Editor: Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College; [email protected] Inside Managing Editor: Carol Baxter, MAA 4 Saunders Mac Lane, 1909-2005 [email protected] By John MacDonald Senior Writer: Harry Waldman, MAA [email protected] 5 Encountering Saunders Mac Lane By David Eisenbud Please address advertising inquiries to: Rebecca Hall [email protected] 8George B. Dantzig 1914–2005 President: Carl C. Cowen By Don Albers First Vice-President: Barbara T. Faires, 11 Convergence: Mathematics, History, and Teaching Second Vice-President: Jean Bee Chan, An Invitation and Call for Papers Secretary: Martha J. Siegel, Associate By Victor Katz Secretary: James J. Tattersall, Treasurer: John W. Kenelly 12 What I Learned From…Project NExT By Dave Perkins Executive Director: Tina H. Straley 14 The Preparation of Mathematics Teachers: A British View Part II Associate Executive Director and Director By Peter Ruane of Publications: Donald J. Albers FOCUS Editorial Board: Rob Bradley; J. 18 So You Want to be a Teacher Kevin Colligan; Sharon Cutler Ross; Joe By Jacqueline Brennon Giles Gallian; Jackie Giles; Maeve McCarthy; Colm 19 U.S.A. Mathematical Olympiad Winners Honored Mulcahy; Peter Renz; Annie Selden; Hortensia Soto-Johnson; Ravi Vakil. 20 Math Youth Days at the Ballpark Letters to the editor should be addressed to By Gene Abrams Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College, Dept. of 22 The Fundamental Theorem of ________________ Mathematics, Waterville, ME 04901, or by email to [email protected]. -

2019 Contents 2019

mathematical sciences news 2019 contents 2019 Editor-in-Chief Tom Bohman Contributing Writers Letter from Department 03 Tom Bohman Head, Tom Bohman Jocelyn Duffy Bruce Gerson Florian Frick 04 Ben Panko Emily Payne Faculty Notes Ann Lyon Ritchie Franziska Weber Graphic Design and Photography 10 Carnegie Mellon University Expanding the Boundaries on Marketing & Communications Summer Undergraduate Research Mellon College of Science Communications 14 Carnegie Mellon University Frick's Fellowship Department of Mathematical Sciences Wean Hall 6113 Pittsburgh, PA 15213 20 cmu.edu/math In Memorium Carnegie Mellon University does not discriminate in admission, employment, or administration of its programs or activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, 24 handicap or disability, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, creed, ancestry, belief, veteran status, or genetic information. Furthermore, Carnegie Mellon University does Alumni News not discriminate and is required not to discriminate in violation of federal, state, or local laws or executive orders. Inquiries concerning the application of and compliance with this statement should be directed to the university ombudsman, Carnegie Mellon University, 5000 Forbes 26 Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, telephone 412-268-1018. Obtain general information about Carnegie Mellon University Student News by calling 412-268-2000. Produced for the Department of Mathematical Sciences by Marketing & Communications, November, 2019, 20-137. ©2019 Carnegie Mellon University, All rights reserved. No 30 part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without written permission from Carnegie Mellon University's Department of Mathematical Sciences. Class of 2019 1 Letter from Mathematics Department Head, Tom Bohman Undergraduate research has become a hallmark of a Carnegie Mellon University education, with students citing that it has helped to prepare them for their futures in academia and the workforce. -

Basic Polyhedral Theory 3

BASIC POLYHEDRAL THEORY VOLKER KAIBEL A polyhedron is the intersection of finitely many affine halfspaces, where an affine halfspace is a set ≤ n H (a, β)= x Ê : a, x β { ∈ ≤ } n n n Ê Ê for some a Ê and β (here, a, x = j=1 ajxj denotes the standard scalar product on ). Thus, every∈ polyhedron is∈ the set ≤ n P (A, b)= x Ê : Ax b { ∈ ≤ } m×n of feasible solutions to a system Ax b of linear inequalities for some matrix A Ê and some m ≤ n ′ ′ ∈ Ê vector b Ê . Clearly, all sets x : Ax b, A x = b are polyhedra as well, as the system A′x = b∈′ of linear equations is equivalent{ ∈ the system≤ A′x }b′, A′x b′ of linear inequalities. A bounded polyhedron is called a polytope (where bounded≤ means− that≤ there − is a bound which no coordinate of any point in the polyhedron exceeds in absolute value). Polyhedra are of great importance for Operations Research, because they are not only the sets of feasible solutions to Linear Programs (LP), for which we have beautiful duality results and both practically and theoretically efficient algorithms, but even the solution of (Mixed) Integer Linear Pro- gramming (MILP) problems can be reduced to linear optimization problems over polyhedra. This relationship to a large extent forms the backbone of the extremely successful story of (Mixed) Integer Linear Programming and Combinatorial Optimization over the last few decades. In Section 1, we review those parts of the general theory of polyhedra that are most important with respect to optimization questions, while in Section 2 we treat concepts that are particularly relevant for Integer Programming.