Images of the Japanese American Internment, 1942-1992

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VISIONS Winter 2005 Please Scroll Down to Begin Reading Our Issue

VISIONS Winter 2005 Please scroll down to begin reading our issue. Thanks! Brian Lee ‘06, Editor in Chief [email protected] LETTER FROM THE EDITORS WINTER 2005 VOLUME vi, ISSUE 1 Welcome to the Winter 2005 issue of VISIONS. We hope We would like to sincerely thank our artists, poets, you enjoy the quality and variety of artistic, poetic, writers, and staff members for making VISIONS Winter and literary contributions celebrating the diversity of 2005 a reality—without all of your hours of work and the Asian American community at Brown. creativity VISIONS could not be where it is today. We would also like to thank Dean Kisa Takesue of the VISIONS boasts a dedicated staff of writers, artists, Third World Center and Office of Student Life, who and designers, and maintains a strong editorial staff serves as the administrative advisor of VISIONS, for dedicated to the constant improvement of this truly her ideas, inspiration, and support. We would like unique publication. As many of you know, since to extend our appreciation to the individuals and our Spring 2004 issue we have been in the process groups who generously sponsored this publication of vastly improving the quality of our publication, and gave us their belief in us to succeed, and we transforming it from a small pamphlet into its current are extremely grateful to our supporters in the Brown form. This has been possible thanks to the efforts of community for taking an interest in this publication our staff members as well as our generous sponsors in and the issues it raises. -

A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas Caleb Kenji Watanabe University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 12-2011 Islands and Swamps: A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas Caleb Kenji Watanabe University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian American Studies Commons, Other History Commons, and the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Watanabe, Caleb Kenji, "Islands and Swamps: A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 206. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/206 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ISLANDS AND SWAMPS: A COMPARISON OF THE JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT EXPERIENCE IN HAWAII AND ARKANSAS ISLANDS AND SWAMPS: A COMPARISON OF THE JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT EXPERIENCE IN HAWAII AND ARKANSAS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Caleb Kenji Watanabe Arkansas Tech University Bachelor of Arts in History, 2009 December 2011 University of Arkansas ABSTRACT Comparing the Japanese American relocation centers of Arkansas and the camp systems of Hawaii shows that internment was not universally detrimental to those held within its confines. Internment in Hawaii was far more severe than it was in Arkansas. This claim is supported by both primary sources, derived mainly from oral interviews, and secondary sources made up of scholarly research that has been conducted on the topic since the events of Japanese American internment occurred. -

Snehal Desai

East West Players and Japanese American Cultural & Community Center (JACCC) By Special Arrangement with Sing Out, Louise! Productions & ATA PRESENT BOOK BY Marc Acito, Jay Kuo, and Lorenzo Thione MUSIC AND LYRICS BY Jay Kuo STARRING George Takei Eymard Cabling, Cesar Cipriano, Janelle Dote, Jordan Goodsell, Ethan Le Phong, Sharline Liu, Natalie Holt MacDonald, Miyuki Miyagi, Glenn Shiroma, Chad Takeda, Elena Wang, Greg Watanabe, Scott Watanabe, and Grace Yoo. SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN PROJECTION DESIGN PROPERTY DESIGN Se Hyun Halei Karyn Cricket S Adam Glenn Michael Oh Parker Lawrence Myers Flemming Baker FIGHT ALLEGIANCE ARATANI THEATRE PRODUCTION CHOREOGRAPHY PRODUCTION MANAGER PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER Cesar Cipriano Andy Lowe Bobby DeLuca Morgan Zupanski COMPANY MANAGER GENERAL MANAGER ARATANI THEATRE GENERAL MANAGER Jade Cagalawan Nora DeVeau-Rosen Carol Onaga PRESS REPRESENTATIVE MARKETING GRAPHIC DESIGN Davidson & Jim Royce, Nishita Doshi Choy Publicity Anticipation Marketing EXECUTIVE PRODUCER MUSIC DIRECTOR ORCHESTRATIONS AND CHOREOGRAPHER ARRANGEMENTS Alison M. Marc Rumi Lynne Shankel De La Cruz Macalintal Oyama DIRECTED BY Snehal Desai The original Broadway production of Allegiance opened on November 8th, 2015 at the Longacre Theatre in NYC and was produced by Sing Out, Louise! Productions and ATA with Mark Mugiishi/Hawaii HUI, Hunter Arnold, Ken Davenport, Elliott Masie, Sandi Moran, Mabuhay Productions, Barbara Freitag/Eric & Marsi Gardiner, Valiant Ventures, Wendy Gillespie, David Hiatt Kraft, Norm & Diane Blumenthal, M. Bradley Calobrace, Karen Tanz, Gregory Rae/Mike Karns in association with Jas Grewal, Peter Landin, and Ron Polson. World Premiere at the Old Globe Theater, San Diego, California. Barry Edelstein, Artistic Director; Michael G. -

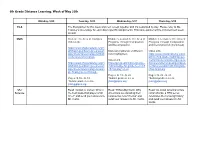

6Th Grade Distance Learning: Week of May 25Th

6th Grade Distance Learning: Week of May 25th Monday, 5/25 Tuesday, 5/26 Wednesday, 5/27 Thursday, 5/28 ELA The ELA packet for this week and next is kept together and not separated by day. Please refer to Ms. Crowley’s cover page for each day’s specific assignments. This same packet will be included next week, as well. Math Review: The Area of Triangles Module 5, Lesson 5: The Area of Module 5, Lesson 5: The Area of Video Link: Polygons Through Composition Polygons Through Composition and Decomposition and Decomposition (Continued) https://www.khanacademy.org/m ath/basic-geo/basic-geo-area-an Materials (optional): 2 different Video Link: d-perimeter/area-triangle/v/intuiti color highlighters https://www.khanacademy.org/m on-for-area-of-a-triangle ath/cc-third-grade-math/imp-geo Video Link: metry/imp-decompose-figures-to- https://www.khanacademy.org/m https://gm.greatminds.org/kotg-e find-area/v/decomposing-shapes- ath/basic-geo/basic-geo-area-an m/knowledge-for-grade-6-em-m5 to-find-area-add-math-3rd-grade- d-perimeter/area-triangle/v/exam -l5?hsLang=en-us khan-academy ple-finding-area-of-triangle Pages: S. 19 - S. 22 Pages: S. 23 - S. 25 Pages: S.16 - S. 18 *Submit problem set to *Submit problem set to *Submit problem set to [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SS / Read “Jordan or James: Who is Read “#ShareMyCheck: Why Read “As Asian Americans face Science the best basketball player of all Americans are donating their racist attacks, a PBS series time?” and send your answers to coronavirus relief checks” and celebrates their unsung history” Mr. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1982

Nat]onal Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1982. Respectfully, F. S. M. Hodsoll Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. March 1983 Contents Chairman’s Statement 3 The Agency and Its Functions 6 The National Council on the Arts 7 Programs 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 30 Expansion Arts 46 Folk Arts 70 Inter-Arts 82 International 96 Literature 98 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 114 Museum 132 Music 160 Opera-Musical Theater 200 Theater 210 Visual Arts 230 Policy, Planning and Research 252 Challenge Grants 254 Endowment Fellows 259 Research 261 Special Constituencies 262 Office for Partnership 264 Artists in Education 266 State Programs 272 Financial Summary 277 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 278 The descriptions of the 5,090 grants listed in this matching grants, advocacy, and information. In 1982 Annual Report represent a rich variety of terms of public funding, we are complemented at artistic creativity taking place throughout the the state and local levels by state and local arts country. These grants testify to the central impor agencies. tance of the arts in American life and to the TheEndowment’s1982budgetwas$143million. fundamental fact that the arts ate alive and, in State appropriations from 50 states and six special many cases, flourishing, jurisdictions aggregated $120 million--an 8.9 per The diversity of artistic activity in America is cent gain over state appropriations for FY 81. -

III. Appellate Court Overturns Okubo-Yamada

III. appellate PACIFIC CrrlZEN court overturns Publication of the National Japanese American Citizens League Okubo-Yamada Vol. 86 No. 1 New Year Special: Jan. 6-13, 1978 20¢ Postpaid U.S. 15 Cents STOCKTON, Calif.-It was a go law firm of Baskin, festive Christmas for the Server and Berke. It is "ex Okubo and Yamada families tremely unlikely" the appel here upon hearing from late court would grant Hil their Chicago attorneys just ton Hotel a rehearing at the before the holidays that the appellate level nor receive Jr. Miss Pageant bars alien aspirants lllinois appellate court had permission to appeal to the SEATTLE-Pacific Northwest JACL leaders concede the "It would seem only right and proper that the pageant reversed the Cook County lllinois supreme court, fight to reinstate a 17-year-{)ld Vietnamese girl of Dayton, rules should be amended to include in their qualifications trial court decision and or Berke added. He said! Wash. who was denied the Touchet Valley Junior Miss dered the 1975 civil suit "The end result, after all of pageant candidates the words 'and aliens legally ad aeainst the Hilton Hotel title because she was not an American citizen has most these petitions, is that we are mitted as pennanent residents of the United States'," Ya Corp. to be reheard going to be given amthero~ likely been lost. mamoto wrote in a letter to the Spokane Spokesman Re The Okubo-Yamada case portunity to try this case or The state Junior Miss Pageant will be held at Wenat view. had alleged a breach of ex settle it before trial" chee Jan. -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Consequences of the Attack on Pearl Harbor from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump to Navigationjump to Search

Consequences of the attack on Pearl Harbor From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search Hideki Tojo, Japanese Prime Minister at the time of the attack Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor took place on December 7, 1941. The U.S. military suffered 18 ships damaged or sunk, and 2,400 people were killed. Its most significant consequence was the entrance of the United States into World War II. The US had previously been neutral but subsequently entered the Pacific War, the Battle of the Atlantic and the European theatre of war. Following the attack, the US interned 120,000 Japanese Americans, 11,000 German Americans, and 3,000 Italian Americans. Contents 1American public opinion prior to the attack 2American response 3Japanese views 4Germany and Italy declare war 5British reaction 6Canadian response 7Investigations and blame 8Rise of anti-Japanese sentiment and historical significance 9Perception of the attack today o 9.1Revisionism controversies 10Analysis o 10.1Tactical implications . 10.1.1Battleships . 10.1.2Carriers . 10.1.3Shore installations . 10.1.4Charts o 10.2Strategic implications 11See also 12Notes 13External links American public opinion prior to the attack[edit] From the outbreak of World War II on September 1, 1939 to December 8, 1941, the United States was officially neutral, as it was bound by the Neutrality Acts not to get involved in the conflicts raging in Europe and Asia. Prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, public opinion in the United States had not been unanimous. When polled in January -

Asians & Pacific Islanders Across 1300 Popular Films (2021)

The Prevalence and Portrayal of Asian and Pacific Islanders across 1,300 Popular Films Dr. Nancy Wang Yuen, Dr. Stacy L. Smith, Dr. Katherine Pieper, Marc Choueiti, Kevin Yao & Dana Dinh with assistance from Connie Deng Wendy Liu Erin Ewalt Annaliese Schauer Stacy Gunarian Seeret Singh Eddie Jang Annie Nguyen Chanel Kaleo Brandon Tam Gloria Lee Grace Zhu May 2021 ASIANS & PACIFIC ISLANDERS ACROSS , POPULAR FILMS DR. NANCY WANG YUEN, DR. STACY L. SMITH & ANNENBERG INCLUSION INITIATIVE @NancyWangYuen @Inclusionists API CHARACTERS ARE ABSENT IN POPULAR FILMS API speaking characters across 1,300 top movies, 2007-2019, in percentages 9.6 Percentage of 8.4 API characters overall 5.9% 7.5 7.2 5.6 5.8 5.1 5.2 5.1 4.9 4.9 4.7 Ratio of API males to API females 3.5 1.7 : 1 Total number of speaking characters 51,159 ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ A total of 3,034 API speaking characters appeared across 1,300 films API LEADS/CO LEADS ARE RARE IN FILM Of the 1,300 top films from 2007-2019... And of those 44 films*... Films had an Asian lead/co lead Films Depicted an API Lead 29 or Co Lead 44 Films had a Native Hawaiian/Pacific 21 Islander lead/co lead *Excludes films w/ensemble leads OF THE 44 FILMS OF THE 44 FILMS OF THE 44 FILMS OF THE 44 FILMS WITH API WITH API WITH API WITH API LEADS/CO LEADS LEADS/CO LEADS LEADS/CO LEADS LEADS/CO LEADS 6 0 0 14 WERE WERE WOMEN WERE WERE GIRLS/WOMEN 40+YEARS OF AGE LGBTQ DWAYNE JOHNSON © ANNENBERG INCLUSION INITIATIVE TOP FILMS CONSISTENTLY LACK API LEADS/CO LEADS Of the individual lead/co leads across 1,300 top-grossing films.. -

Living Voices Within the Silence Bibliography 1

Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 1 Within the Silence bibliography FICTION Elementary So Far from the Sea Eve Bunting Aloha means come back: the story of a World War II girl Thomas and Dorothy Hoobler Pearl Harbor is burning: a story of World War II Kathleen Kudlinski A Place Where Sunflowers Grow (bilingual: English/Japanese) Amy Lee-Tai Baseball Saved Us Heroes Ken Mochizuki Flowers from Mariko Rick Noguchi & Deneen Jenks Sachiko Means Happiness Kimiko Sakai Home of the Brave Allen Say Blue Jay in the Desert Marlene Shigekawa The Bracelet Yoshiko Uchida Umbrella Taro Yashima Intermediate The Burma Rifles Frank Bonham My Friend the Enemy J.B. Cheaney Tallgrass Sandra Dallas Early Sunday Morning: The Pearl Harbor Diary of Amber Billows 1 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 2 The Journal of Ben Uchida, Citizen 13559, Mirror Lake Internment Camp Barry Denenberg Farewell to Manzanar Jeanne and James Houston Lone Heart Mountain Estelle Ishigo Itsuka Joy Kogawa Weedflower Cynthia Kadohata Boy From Nebraska Ralph G. Martin A boy at war: a novel of Pearl Harbor A boy no more Heroes don't run Harry Mazer Citizen 13660 Mine Okubo My Secret War: The World War II Diary of Madeline Beck Mary Pope Osborne Thin wood walls David Patneaude A Time Too Swift Margaret Poynter House of the Red Fish Under the Blood-Red Sun Eyes of the Emperor Graham Salisbury, The Moon Bridge Marcia Savin Nisei Daughter Monica Sone The Best Bad Thing A Jar of Dreams The Happiest Ending Journey to Topaz Journey Home Yoshiko Uchida 2 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 3 Secondary Snow Falling on Cedars David Guterson Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet Jamie Ford Before the War: Poems as they Happened Drawing the Line: Poems Legends from Camp Lawson Fusao Inada The moved-outers Florence Crannell Means From a Three-Cornered World, New & Selected Poems James Masao Mitsui Chauvinist and Other Stories Toshio Mori No No Boy John Okada When the Emperor was Divine Julie Otsuka The Loom and Other Stories R.A. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES and CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1994 MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994 A retrospective celebrating the seventieth anniversary of Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer, the legendary Hollywood studio that defined screen glamour and elegance for the world, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on June 24, 1994. MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS comprises 112 feature films produced by MGM from the 1920s to the present, including musicals, thrillers, comedies, and melodramas. On view through September 30, the exhibition highlights a number of classics, as well as lesser-known films by directors who deserve wider recognition. MGM's films are distinguished by a high artistic level, with a consistent polish and technical virtuosity unseen anywhere, and by a roster of the most famous stars in the world -- Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Judy Garland, Greta Garbo, and Spencer Tracy. MGM also had under contract some of Hollywood's most talented directors, including Clarence Brown, George Cukor, Vincente Minnelli, and King Vidor, as well as outstanding cinematographers, production designers, costume designers, and editors. Exhibition highlights include Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1925), Victor Fleming's Gone Hith the Hind and The Wizard of Oz (both 1939), Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Ridley Scott's Thelma & Louise (1991). Less familiar titles are Monta Bell's Pretty Ladies and Lights of Old Broadway (both 1925), Rex Ingram's The Garden of Allah (1927) and The Prisoner - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 of Zenda (1929), Fred Zinnemann's Eyes in the Night (1942) and Act of Violence (1949), and Anthony Mann's Border Incident (1949) and The Naked Spur (1953).