The Integration of the Opelika, Alabama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birmingham, Alabama Event Hosted by Bill & Linda Daniels Re

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu April 8, 1994 TO: SENATOR DOLE FROM: MARCIE ADLER RE: BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA EVENT HOSTED BY BILL & LINDA DANIELS RE: ELIEHUE & NANCY BRUNSON ELIEHUE BRUNSON, FORMER KC REGIONAL ADMINISTRATOR, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR, HAS ADVISED ME THAT HE IS ATTENDING THIS EVENT AND HAS OFFERED TO HELP US IN THE ALABAMA AREA. (I'M SENDING THAT INFO TO C.A.) ELIEHUE WAS APPOINTED BY PRESIDENT BUSH AND DROVE MRS. DOLE DURING THE JOB CORPS CENTER DEDICATION IN MANHATTAN. ALTHOUGH LOW-KEY, HE DID WATCH OUT FOR OUR INTERESTS DURING THE JOB CORPS COMPLETION. HE ALSO DEFUSED A POTENTIAL RACIALLY SENSITIVE SITUATION IN KCK WHEN GALE AND I WERE STUMPED AND CALLED HIM FOR ADVICE. ELIEHUE AND NANCY MOVED TO BIRMINGHAM AFTER TCI - COMMUNICATIONS HIRED HIM TO SERVE AS REGIONAL GENERAL COUNSEL. YOUR LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION WAS A KEY FACTOR IN HIS HIRE. Page 1 of 55 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 111 AP 04-08-94 12:06 EST 29 Lines. Copyright 1994. All rights reserved. PM-AL-ELN--Governor-James,200< URGENT< Fob James to Run for Governor Again as Republican< BIRMINGHAM, Ala. (AP) Former Gov. Fob James decided toda to make a fourth bid fo s a Re ublican. Jack Williams, executive director of the Republican Legislative Caucus and chairman of the Draft Fob James Committee, said James would qualify at 3 p.m. today at the State Republicans Headquarters in Birmingham. -

State of the Soutern States

72 NEW SOUTH/FALU1968 STATE OF THE SOUTHERN STATES This round-up of events, developments and trends in civil rights, justice, politics, employment and other aspects of southern change, advancement and setback, comes from the Southern Regional Council staff and professional reporters. ALABAMA The three-judge federal court which dom of choice and institute a system of supervises Alabama's statewide school de zoning, consolidation, or pairing in order segregation suit rejected on October 18 to end the dual school system. pleas from both Gov. Albert Brewer and Meanwhile, Mobile schools-which are the Alabama Education Association, which not covered by the statewide desegrega represents most of the state's 21,000 white tion order but are under a separate suit teachers, to modify an order of August 28 enrolled 2,800 Negro children in formerly directing 76 school systems to carry out white schools and 253 white children in extensive faculty and pupil desegregation. formerly all-Negro schools. This compares Governor Brewer arg ued that the with 632 Negro children who enrolled in court's order imposed " an impossible formerly all-white schools last year. The task" on local school superintendents and Mobile school system, the state's largest urged local officials not to cooperate with with 75,000 pupils, is operating under a the Justice Department, which he called limited zoning plan to achieve desegre "our adversary." gation. The court found, however, that 57 of Also on the education front, Gov. the 76 school districts had already com Brewer gave the teachers a four per cent plied with the court's directives or had pay raise as the new school year began. -

Utz on Gaillard, 'Cradle of Freedom: Alabama and the Movement That Changed America'

H-1960s Utz on Gaillard, 'Cradle of Freedom: Alabama and the Movement That Changed America' Review published on Monday, August 1, 2005 Frye Gaillard. Cradle of Freedom: Alabama and the Movement That Changed America. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004. xvi + 419 pp. $34.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8173-1388-3. Reviewed by Karen Utz (University of Alabama Birmingham) Published on H-1960s (August, 2005) Alabama's Struggle for Justice Some of the key events of the civil rights movement took place in Alabama. Frye Gaillard's Cradle of Freedom focuses on the Montgomery Bus Boycott, George Wallace's infamous stand in the doorway at the University of Alabama, the Freedom Rides, the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, and Bloody Sunday. This fine book speaks to the bravery and wisdom of the leaders and legends of the movement--Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., Stokley Carmichael, and Fred Shuttlesworth, who claimed that for him the cause took "divine insanity" (p.106). The strength of this extraordinary story is Gaillard's compelling portrayal of the early civil rights leaders, as well as all the ordinary "apostles of decency," both black and white, who believed it was possible to build a better world (p.xvi). Gaillard recognizes such overlooked individuals as Charles Gomillion, a professor at Tuskegee Institute who spent over thirty years crusading for black voting rights, and Vernon Johns, King's eloquent predecessor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, who continually spoke out against the "indignities of segregation" (p.xvi). Twenty years earlier, Alabamian Aubrey William, Roosevelt's director of the National Youth Administration, championed the concept of work relief and provided jobs to young black and white males during the Great Depression. -

Alabama Elections Collection

Alabama Elections Collection Guide to the ALABAMA ELECTIONS COLLECTION Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections Montgomery, Alabama TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Background Information 4 Scope and Content Note 4 Arrangement 4-6 Inventory 6-7 1 Alabama Elections Collection Collection Summary Creator: This collection has been artificially constructed from a variety of sources. No information is available on the compiling of materials in this collection. Title: Alabama Elections Dates: 1936- 1976 Quantity: 2 boxes. Linear feet: 1.0. Identification: 88/1 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Alabama Elections Collection, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: This collection has been artificially constructed from a variety of sources. No information is available on the compiling of materials in this collection. Processing By: Rickey Best Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1988); Samantha McNeilly, Archives Assistant (2006) Copyright Information: Copyright not assigned to the AUM Library. Restrictions 2 Alabama Elections Collection Restrictions on access There are no restrictions on access to these papers. Restrictions on usage Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public -

City Council Correspondence; Mayoral Correspondence; Reading Files; Reports, Booklets, and Pamphlets; and Personal Files

Vann, David Johnson Papers, 1959-1979 Biography/Background: David Johnson Vann was born August 10, 1928 in Randolph County, Alabama. Vann graduated from the University of Alabama in 1950, and from the University's law school in 1951. He served as clerk to United States Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, and was present in the courtroom when the court handed down the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision. After completing his term as court clerk Vann settled in Birmingham and joined the law firm of White, Bradley, Arant, All and Rose. In 1963 Vann helped organize a referendum that changed Birmingham's form of government from a three-member commission to a mayor and nine-member council. Vann served as a special assistant to Birmingham mayor Albert Boutwell under the new city government. In 1971 Vann was elected to the Birmingham city council. That same year he helped lead an unsuccessful campaign, known as "One Great City," to consolidate the city governments of Birmingham and its suburbs into a single countywide municipal government. Vann was elected mayor of Birmingham in 1975 and served one term, losing his bid for reelection to Richard Arrington, Jr. In 1980 Vann became a lobbyist and special council to Arrington, and served two terms as chair of the Birmingham Water Works and Sewer Board. As council to the mayor Vann oversaw an aggressive annexation campaign, adding substantial areas south of Birmingham to the city limits and frustrating efforts by several Birmingham suburbs to block the city's growth. Vann was active in civic organizations and was a founding board member of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. -

The Perceptions of Race and Identity in Birmingham

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Capstone Collection SIT Graduate Institute Spring 5-25-2014 The eP rceptions of Race and Identity in Birmingham: Does 50 Years Forward Equal Progress? Lisa Murray SIT Graduate Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones Part of the Political History Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Murray, Lisa, "The eP rceptions of Race and Identity in Birmingham: Does 50 Years Forward Equal Progress?" (2014). Capstone Collection. 2658. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones/2658 This Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Graduate Institute at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Perceptions of Race and Identity in Birmingham: Does 50 Years Forward Equal Progress? Lisa Jane Murray PIM 72 A Capstone Paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Arts in Conflict Transformation and Peacebuilding at SIT Graduate Institute in Brattleboro, Vermont, USA. May 25, 2014 Advisor: John Ungerleider I hereby grant permission for World Learning to publish my capstone on its websites and in any of its digital/electronic collections, and to reproduce and transmit my CAPSTONE ELECTRONICALLY. I understand that World Learning’s websites and digital collections are publicly available via the Internet. I agree that World Learning is NOT responsible for any unauthorized use of my capstone by any third party who might access it on the Internet or otherwise. -

A&T Four Box 0002

Inventory of the A&T Four Collection, Box 002 Contact Information Archives and Special Collections F.D. Bluford Library North Carolina A&T State University Greensboro, NC 27411 Telephone: 336-285-4176 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ncat.edu/resources/archives Descriptive Summary Repository F. D. Bluford Library Archives and Special Collections Creator Franklin McCain Ezell Blair, Jr. (Jibreel Khazan) David Richmond, Sr. Joseph Mc Neil Title “A&T Four” Box #2 Language of Materials English Extent 1 archival boxes, 121 items, 1.75 linear feet Abstract The Collection consists Events programs and newspaper articles and editorials commemorating the 1960 sit-ins over the years from 1970s to 2000s. The articles cover how A&T, Greensboro and the nation honor the Four and the sit-in movement and its place in history. They also put it in context of racial relations contemporary with their publication. Administrative Information Restrictions to Access No Restrictions Acquisitions Information Please consult Archives Staff for additional information. Processing Information Processed by James R. Jarrell, April 2005; Edward Lee Love, Fall 2016. Preferred Citation [Identification of Item], in the A&T Four Box 2, Archives and Special Collections, Bluford Library, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, Greensboro, NC. Copyright Notice North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College owns copyright to this collection. Individuals obtaining materials from Bluford Library are responsible for using the works in conformance with United State Copyright Law as well as any restriction accompanying the materials. Biographical Note On February 1, 1960, NC A&T SU freshmen Franklin McCain, David Richmond, Joseph McNeil, and Ezell Blair (Jibreel Khazan) sat down at the whites only lunch counter at the F.W. -

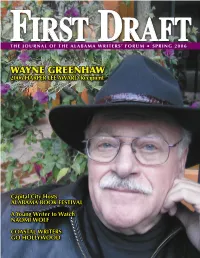

Vol. 12, No.2 / Spring 2006

THE JOURNAL OF THE ALABAMA WRITERS’ FORUM FIRST DRAFT• SPRING 2006 WAYNE GREENHAW 2006 HARPER LEE AWARD Recipient Capital City Hosts ALABAMA BOOK FESTIVAL A Young Writer to Watch NAOMI WOLF COASTAL WRITERS GO HOLLYWOOD FY 06 BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD MEMBER PAGE President LINDA HENRY DEAN Auburn Words have been my life. While other Vice-President ten-year-olds were swimming in the heat of PHILIP SHIRLEY Jackson, MS summer, I was reading Gone with the Wind on Secretary my screened-in porch. While my friends were JULIE FRIEDMAN giggling over Elvis, I was practicing the piano Fairhope and memorizing Italian musical terms and the Treasurer bios of each composer. I visited the local library DERRYN MOTEN Montgomery every week and brought home armloads of Writers’ Representative books. From English major in college to high JAMES A. BUFORD, JR. school English teacher in my early twenties, Auburn I struggled to teach the words of Shakespeare Writers’ Representative and Chaucer to inner-city kids who couldn’t LINDA C. SPALLA read. They learned to experience the word, even Huntsville Linda Spalla serves as Writers’ Repre- DARYL BROWN though they couldn’t read it. sentative on the AWF Executive Com- Florence Abruptly moving from English teacher to mittee. She is the author of Leading RUTH COOK a business career in broadcast television sales, Ladies and a frequent public speaker. Birmingham I thought perhaps my focus would be dif- JAMES DUPREE, JR. fused and words would lose their significance. Surprisingly, another world of words Montgomery appeared called journalism: responsibly chosen words which affected the lives of STUART FLYNN Birmingham thousands of viewers. -

Reaction and Reform: Transforming Under Alabama's Constitution, 190 1-1975

REACTIONAND REFORM:TRANSFORMING THE JUDICIARY UNDERALABAMA'S CONSTITUTION, 190 1-1975 Tony A. Freyer* Paul M. Pruitt, Jr.** During the twentieth century Alabama's Constitution of 1901 proved resistant to change. At the turn of the century, the constitution emerged from a predominately small-town, rural society and a political order controlled by a Democratic Party committed to white supremacy. Over the course of the seven decades that followed, amid the Great De- pression, World War 11, and the Civil Rights struggle, leaders of the state's social and political order appealed to the legitimacy the constitu- tion represented to justify the status quo.' Ultimately, with the support of the United States Supreme Court and the federal judiciary, the na- tional government, and Northern public opinion, African-Americans overcame the Alabama Constitution's sanction of Jim Crow.' This was a case of forced change. Alabamians revealed, however, a greater facil- ity for adapting the constitution to changing times in the campaign to reform the state's judicial system which lawyers organized under the - - - - University Research Professor of History and Law, The University of Alabama. For support, Professor Freyer thanks Dean Kenneth C. Randall, The Alabama Law School Founda- tion, and the Edward Brett Randolph Fund; he is also indebted to the research of former law students Thomas W. Scroggins. Byron E. House, Brad Murrary. Sean P. Costello, and Ben Wilson cited below. " Assistant Law Librarian, Bounds Law Library. Thanks for encouragement and support to Dean Kenneth C. Randall, to Professor Timothy L. Coggins of The University of Richmond School of Law. -

Air Pollution, Politics, and Environmental Reform in Birmingham, Alabama J. Merritt Mckinney Doctor of Philosophy

RICE UNIVERSITY Air Pollution, Politics, and Environmental Reform in Birmingham, Alabama 1940-1971 by J. Merritt McKinney A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: . Boles, Chair am P. Hobby Professor of History Martin V. Melosi Professor of History University of Houston ~~ Assistant Professor of History Daniel Cohan Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering HOUSTON, TEXAS OCTOBER 2011 Copyright J. Merritt McKinney 2011 ABSTRACT Air Pollution, Politics, and Environmental Reform in Birmingham, Alabama, 1940-1971 by J. Merritt McKinney This dissertation contends that efforts to reduce air pollution in Birmingham, Alabama, from the 1940s through the early 1970s relied on citizens who initially resisted federal involvement but eventually realized that they needed Washington's help. These activists had much in common with clean air groups in other U.S. cities, but they were somewhat less successful because of formidable industrial opposition. In the 1940s the political power of the Alabama coal industry kept Birmingham from following the example of cities that switched to cleaner-burning fuels. The coal industry's influence on Alabama politics had waned somewhat by the late 1960s, but U.S. Steel and its allies wielded enough political power in 1969 to win passage of a weak air pollution law over one favored by activists. Throughout this period the federal government gradually increased its involvement in Alabama's air pollution politics, culminating in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the enactment of environmental laws that empowered federal officials to pressure Alabama to pass a revised 1971 air pollution law that met national standards. -

Journal in Entirety

EDITOREDITOR RobertRobert Danielson Danielson EDITORIAL BOARD KennethEDITORIAL J. Collins BOARD Professor of HistoricalKenneth Theology J. Collins and Wesley Studies Professor of Historical Theology and Wesley Studies J. Steven O’Malley Professor ofJ. MethodistSteven O’Malley Holiness History Professor of Methodist Holiness History EDITORIAL ADVISORY PANEL William Abraham,EDITORIAL Perkins ADVISORY School PANEL of Theology WilliamDavid Bundy, Abraham, New York Perkins Theological School Seminaryof Theology DavidTed Campbell, Bundy, New Perkins York School Theological of Theology Seminary HyungkeunTed Campbell, Choi, SeoulPerkins Theological School of University Theology RichardHyungkeun Heitzenrater, Choi, Duke Seoul University Theological Divinity University School RichardScott Heitzenrater, Kisker, Wesley Duke Theological University Seminary Divinity School Sarah Lancaster, Methodist Theological School of Ohio Scott Kisker, Wesley Theological Seminary Gareth Lloyd, University of Manchester Sarah Lancaster, Methodist Theological School of Ohio Randy Maddox, Duke University Divinity School Gareth Lloyd, University of Manchester Nantachai Medjuhon, Muang Thai Church, Bangkok, Thailand RandyStanley Maddox, Nwoji, Duke Pastor, University Lagos, NigeriaDivinity School NantachaiPaul Numrich, Medjuhon, Theological Muang Consortium Thai Church, of Greater Bangkok, Columbus Thailand StanleyDana Robert,Nwoji, BostonPastor, UniversityLagos, Nigeria PaulHoward Numrich, Snyder, Theological Manchester Consortium Wesley Research of Greater Centre Columbus -

The History of Two-Year Education

A CENTURY OF CHANGE: THE HISTORY OF TWO-YEAR EDUCATION IN THE STATE OF ALABAMA, 1866 - 1963 by DUSTIN P. SMITH STEPHEN G. KATSINAS, COMMITTEE CHAIR KARI A. FREDERICKSON WAYNE J. URBAN NATHANIEL J. BRAY ROBERT P. PEDERSEN A DOCTORAL DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in the Department of Educational Leadership, Policy and Technology Studies in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright Dustin P. Smith ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Much has been written about two-year education in Alabama during the governorships of George C. Wallace, but little about two-year education prior to his first inauguration in 1963. Yet nearly a third of the forty-three junior, technical, and community college institutions that eventually formed the Alabama Community College System had been established prior to 1963. This study reviews the major types of two-year colleges (historically black private junior college, public trade schools, and public junior colleges) established in Alabama from 1866 to 1963 by drawing upon case studies of institutional founding based upon primary document analysis. Alabama’s first two-year institution was Selma University established in 1878 by the Alabama Colored Baptist Convention. Selma University operated as a private junior college for the newly freed slaves hungry for education. The first public two-year institution was the Alabama School of Trades, founded in Gadsden in 1925, which offered vocational education courses. A second trade school was established using federal vocational aid money in Decatur to produce trained workers to support the World War II war efforts.