Problems for Pale Male: an Analysis of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’S Nest Destruction Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 Bed for Sale $39,500,000 New York, NY Ref: 19199709

6 Bed For Sale $39,500,000 New York, NY Ref: 19199709 5th Ave & 74th St - Private Full Floor - 14 Rooms Distinguished full floor residence perched on the 9th floor of one of Fifth Avenue's most prestigious white-glove cooperatives. This extraordinary 14-room, 6-bedroom apartment offers grand proportions enhanced by a gracious layout spanning over 5500 square feet. This spectacular prewar apartment has 55-feet fronting Central Park and features soaring 10'6" foot ceilings, original herringbone flooring, and impressive original plaster moldings throughout. Sunlight streams in through 27 oversized windows spanning all four exposures. A private elevator landing opens into the main gallery, which has a deep coat closet and is bathed in natural light from the adjoining living room, library, and formal dining room. The gallery has a doublewide ent... Telephone: 246 537 0840 Email: [email protected] Rosebank, Derricks, St. James, BB24008, Barbados Gallery Telephone: 246 537 0840 Email: [email protected] Rosebank, Derricks, St. James, BB24008, Barbados Property Description Location: New York, NY 5th Ave & 74th St - Private Full Floor - 14 Rooms Distinguished full floor residence perched on the 9th floor of one of Fifth Avenue's most prestigious white-glove cooperatives. This extraordinary 14-room, 6-bedroom apartment offers grand proportions enhanced by a gracious layout spanning over 5500 square feet. This spectacular prewar apartment has 55-feet fronting Central Park and features soaring 10'6" foot ceilings, original herringbone flooring, and impressive original plaster moldings throughout. Sunlight streams in through 27 oversized windows spanning all four exposures. A private elevator landing opens into the main gallery, which has a deep coat closet and is bathed in natural light from the adjoining living room, library, and formal dining room. -

In the Nature of Cities: Urban Political Ecology

In the Nature of Cities In the Nature of Cities engages with the long overdue task of re-inserting questions of nature and ecology into the urban debate. This path-breaking collection charts the terrain of urban political ecology, and untangles the economic, political, social and ecological processes that form contemporary urban landscapes. Written by key political ecology scholars, the essays in this book attest that the re- entry of the ecological agenda into urban theory is vital, both in terms of understanding contemporary urbanization processes, and of engaging in a meaningful environmental politics. The question of whose nature is, or becomes, urbanized, and the uneven power relations through which this socio-metabolic transformation takes place, are the central themes debated in this book. Foregrounding the socio-ecological activism that contests the dominant forms of urbanizing nature, the contributors endeavour to open up a research agenda and a political platform that sets pointers for democratizing the politics through which nature becomes urbanized and contemporary cities are produced as both enabling and disempowering dwelling spaces for humans and non-humans alike. Nik Heynen is Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Maria Kaika is Lecturer in Urban Geography at the University of Oxford, School of Geography and the Environment, and Fellow of St. Edmund Hall, Oxford. Erik Swyngedouw is Professor at the University of Oxford, School of Geography and the Environment, and Fellow of St. Peter’s College, Oxford. Questioning Cities Edited by Gary Bridge, University of Bristol, UK and Sophie Watson, The Open University, UK The Questioning Cities series brings together an unusual mix of urban scholars under the title. -

Annual Report 2017

Central Park Conservancy ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Table of Contents 2 Partnership 4 Letter from the Conservancy President 5 Letter from the Chairman of the Board of Trustees 6 Letter from the Mayor and the Parks Commissioner 7 Serving New York City’s Parks 8 Forever Green 12 Honoring Douglas Blonsky 16 Craftsmanship 18 Native Meadow Opens in the Dene Landscape 20 Electric Carts Provide Cleaner, Quieter Transportation 21 Modernizing the Toll Family Playground 22 Restoring the Ramble’s Watercourse 24 Enhancing and Diversifying the Ravine 26 Conservation of the Seventh Regiment Memorial 27 Updating the Southwest Corner 28 Stewardship 30 Operations by the Numbers 32 Central Park Conservancy Institute for Urban Parks 36 Community Programs 38 Volunteer Department 40 Friendship 46 Women’s Committee 48 The Greensward Circle 50 Financials 74 Supporters 114 Staff & Volunteers 124 Central Park Conservancy Mission, Guiding Principle, Core Values, and Credits Cover: Hallett Nature Sanctuary, Left: Angel Corbett 3 CENTRAL PARK CONSERVANCY Table of Contents 1 Partnership Central Park Conservancy From The Conservancy Chairman After 32 years of working in Central Park, Earlier this year Doug Blonsky announced that after 32 years, he would be stepping down as the it hasn’t been an easy decision to step Conservancy’s President and CEO. While his accomplishments in that time have been too numerous to count, down as President and CEO. But this it’s important to acknowledge the most significant of many highlights. important space has never been more First, under Doug’s leadership, Central Park is enjoying the single longest period of sustained health in its beautiful, better managed, or financially 160-year history. -

Central Park Conservancy

Central Park Conservancy ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Table of Contents 2 Partnership 4 Letter from the Chairman of the Board of Trustees and the Conservancy President 5 Letter from the Mayor and the Parks Commissioner 6 Forever Green 10 Craftsmanship 12 Historic Boat Landings Reconstructed at the Lake 16 Perimeter Reconstruction Enhances the East 64th Street Entrance 17 Northern Gateway Restored at the 110th Street Landscape 18 Putting the Adventure Back Into Adventure Playground 20 The Conservation of King Jagiello 22 Southwest Corner Update: Pedestrian-Friendly Upgrades at West 63rd Street 24 Infrastructure Improves the Experience at Rumsey Playfield Landscape 26 Woodlands Initiative Update 30 Stewardship 32 Volunteer Department 34 Operations by the Numbers 40 Central Park Conservancy Institute for Urban Parks 44 Community Programs 46 Friendship 54 Women’s Committee 55 The Greensward Circle 56 Financials 82 Supporters 118 Staff & Volunteers 128 Central Park Conservancy Mission, Guiding Principle, Core Values, and Credits Cover: Hernshead Landing Left: Raymond Davy 3 CENTRAL PARK CONSERVANCY Table of Contents 1 Partnership Central Park Conservancy The City of New York This was an exciting year for the Our parks are not only the green spaces where we go to exercise, experience nature, relax, and spend Conservancy. In spring, we launched our time with family and friends. For many New Yorkers, they are also a lifeline and places to connect with their most ambitious campaign to date, Forever community and the activities that improve quality of life. They are critical to our physical and mental Green: Ensuring the Future of Central well-being and to the livability and natural beauty of our City. -

A 'Tale' to Tell

RIGHT AS REYNA VOL 33, NO. 32 APRIL 25, 2018 Spotlight www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com BON on trans FOSTER Event honors author/ Pat Logue. Photo by Kat Fitzgerald 10 activist PAGE 6 Reyna Ortiz. ‘HUMAN’ Photo courtesy of Ortiz INTEREST Center holds annual Samira Wiley. Human First gala. Photo courtesy of Hulu Photo of Dr. David Gitomer and Dr. Tom Klein by Kat Fitzgerald 8 A ‘TALE’ DEEPA PATEL South Asian lesbian activist dies. TO TELL Photo from Patel’s family 4 Out actress Samira CARMEN Wiley on the second YULIN CRUZ San Juan mayor visits season of The Chicago area. Photo of Cruz with U.S. Rep. Luis Gutierrez by Carrie Maxwell Handmaid’s Tale PAGE 22 12 @windycitytimes1 /windycitymediagroup @windycitytimes www.windycitymediagroup.com 2 April 25, 2018 WINDY CITY TIMES LGBT CRUISES & TOUR EVENTS AL U 17th ANN Halloween Cruise from Oct 28- Nov 4, 2018 7 Day Western Caribbean Cruise from Galveston $599 Royal Caribbean’s Liberty of the Seas Ports: Galveston, Roatan, Costa Maya, Cozumel plus 2 FREE Open Bar Cocktail Parties! Starring: Miss Conception Billy Gilman from “The VOICE” Amy & Freddy Private shows with guest celebrities * $1000 in Costume Prizes Gay DJ * Afternoon T-DanceThemed Dance Parties * Group Dining on most cruise lines * Optional Gay Beach Parties* Single, Couples, & Lesbian Get-Togethers and much more! (800) 592-9058 / AquafestCruises.com WINDY CITY TIMES April 25, 2018 3 NEWS When A Great Deal Matters, Shop Rob Paddor’s... Obits: Deepa Patel, Sharon O’Flynn 4 Activist Donna Red Wing dies 4 Evanston Subaru in Skokie Forum on -

Central Park Conservancy Annual Report 2009

Central Park Conservancy Annual Report 2009 Cover Contents Partnership Craftsmanship Stewardship Friendship Storm Financials Lists Support Info #1 Table of Contents 2 Central Park Conservancy Annual Report 2009 Partnership » Letter from Chairman of the Board of Trustees and President . .3 » Letter from the Mayor and Parks Commissioner . .4 Craftsmanship » Map of Capital Projects . .5 » Central Park’s Playgrounds . .6 » Ancient Playground . .7 » Ancient Playground: William Church Osborn Memorial Gates . .8 » Tarr Family Playground . .9 » Landscape South of the Mount and Conservatory Garden . .10 » The Lake: Ramble Shoreline . .11 » The Lake: Oak Bridge . .13 » West 69th Street Entrance . .15 Stewardship » Operations: Zone Gardeners . .16 » Operations: Volunteer Programs and Environmental Initiatives . .17 » Research: The Survey and “The Central Park Effect” . .18 » Public Programs: Tours and Recreation . .19 Friendship » Special Events and Programs . .20 Special Report: The Storm . .23 Financials . .26 Lists » Board of Trustees . .39 » Women’s Committee; Conservancy Councils . .40 » Contributors . .41 » Women’s Committee Programs and Events . .57 » Conservancy Special Events . .60 » Staff and Volunteers . .61 Ways to Support the Park . .66 Info and Credits . .67 Cover Contents Partnership Craftsmanship Stewardship Friendship Storm Financials Lists Support Info #2 Partnership 3 Central Park Conservancy We are at a critical moment in the history of both the original goal of $100 million and completed proud to say that the Park’s structures -

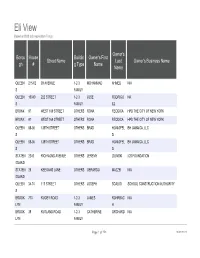

Eli View Based on DOB Job Application Filings

Eli View Based on DOB Job Application Filings Owner's Borou House Buildin Owner's First Street Name Last Owner's Business Name gh # g Type Name Name QUEEN 215-02 93 AVENUE 1-2-3 MOHAMMAD AHMED N/A S FAMILY QUEEN 10040 222 STREET 1-2-3 JOSE RODRIGU NA S FAMILY EZ BRONX 97 WEST 169 STREET OTHERS RONA REODICA HPD THE CITY OF NEW YORK BRONX 97 WEST 169 STREET OTHERS RONA REODICA HPD THE CITY OF NEW YORK QUEEN 88-36 139TH STREET OTHERS BRAD HONIGFEL BH JAMAICA, LLC S D QUEEN 88-36 139TH STREET OTHERS BRAD HONIGFEL BH JAMAICA, LLC S D STATEN 2245 RICHMOND AVENUE OTHERS JEREMY ZILINSKI ICS FOUNDATION ISLAND STATEN 26 KEEGANS LANE OTHERS GERARDO MAZZEI N/A ISLAND QUEEN 34-74 113 STREET OTHERS JOSEPH SCALISI SCHOOL CONSTRUCTION AUTHORITY S BROOK 770 RUGBY ROAD 1-2-3 JAMES ROHRBAC N/A LYN FAMILY H BROOK 39 RUTLAND ROAD 1-2-3 CATHERINE ORCHARD N/A LYN FAMILY Page 1 of 758 10/02/2021 Eli View Based on DOB Job Application Filings Owner 's Owner'sHouse Street Owner'sPh House City State Zip Name one # Numb er 6466575108 6467122941 2128638576 2128638576 9735976433 9735976433 9176828725 7186056119 7184728000 4153122979 3474747144 Page 2 of 758 10/02/2021 Eli View Based on DOB Job Application Filings BRONX 1000 EAST TREMONT OTHERS ROBERT MURPHY NY SCHOOL CONSTRUCTION AVENUE AUTHORITY BROOK 200 LINCOLN ROAD 1-2-3 ERIC BAKER N/A LYN FAMILY BROOK 94 DOUGLASS STREET 1-2-3 OMRI BAR- 94 DOUGLASS LLC LYN FAMILY MASHIAH STATEN 667 HUNTER AVENUE 1-2-3 MILENA KOSZALK NOT APPLICABLE ISLAND FAMILY A BROOK 5909 BEVERLY ROAD OTHERS COLIN ALBERT NYC SCHOOL CONSTRUCTION -

CENTRAL PARK CONSERVANCY ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Table of Contents

CENTRAL PARK CONSERVANCY ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Table of Contents 2 PARTNERSHIP 4 Letter from the Chairman and the President & CEO 5 Letter from the City of New York 6 CRAFTSMANSHIP 8 Capping the Restoration of Central Park’s North End 12 Restoring the Belvedere’s Grandeur 14 New Adventures Await at Safari Playground 16 Reviving Rustic Character at Billy Johnson Playground 18 STEWARDSHIP 20 Spotlight on Operations 24 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT 26 Visitor Experience 28 Volunteers 30 Youth Education 32 HELPING OTHER PARKS 34 Central Park Conservancy Institute for Urban Parks 36 Supporting New York City’s Public Spaces 38 FRIENDSHIP 48 Women’s Committee 50 The Greensward Circle 52 FINANCIALS 78 SUPPORTERS 122 STAFF & VOLUNTEERS 132 CENTRAL PARK CONSERVANCY MISSION, GUIDING PRINCIPLE, CORE VALUES, AND CREDITS Cover: the Belvedere 6 1 CENTRAL PARK CONSERVANCY TABLE OF CONTENTS Partnership From the Chairman and From the City the President & CEO of New York Central Park has never looked more beautiful nor welcomed The Central Park Conservancy’s principal role is to restore, For New Yorkers, parks are vital green spaces that provide This past year, the Conservancy made many other wonderful more visitors. It remains the most iconic of all New York City enhance, and manage the Park for the enjoyment of every respite from urban life. Central Park is one of our City’s enhancements to Central Park. This included its ongoing landmarks, and the most beloved of all retreats from the visitor. We have grown into this role and accomplished the most welcoming and inclusive year-round backyards: a restoration of the Park’s playgrounds. -

Lobbyists 2021 617.646.1000 - Boston - Washington Dc Greg M

Directory of Massachusetts LOBBYISTS 2021 617.646.1000 - www.oneillandassoc.com BOSTON - WASHINGTON DC GREG M. PETER J. MATTHEW P. VICTORIA E. D’AGOSTINO D’AGOSTINO MCKENNA IRETON Providing comprehensive state and municipal advocacy. PRACTICE AREAS: TRANSPORTATION | HEALTH CARE PUBLIC SAFETY | REGULATIONS | ENERGY ENVIRONMENT | CANNABIS FINANCIAL SERVICES | EMERGING INDUSTRIES WWW . T ENAXSTRATEGI E S . COM Theodore J. Aleixo, Jr. Joseph D. Alviani Rafael Antigua A Essential Strategies Inc. Alviani Associates (Joseph D. JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. One State Street, Suite 1100 Alviani dba Alviani Associates) 4 New York, Plz Floor, 17 Anthony Arthur Abdelahad Boston, MA 02109 8 Holbeck Corner New York, NY 10004 Ventry Associates LLP (617) 227-6666 Plymouth, MA 02360 (212) 499-1404 (617) 645-5628 1 Walnut Street Daniel Allegretti Chelsea Elizabeth Aquino- Boston, MA 02108 Exelon Generation Company, LLC Oamshri Amarasingham Fenstermaker (617) 423-0028 1 Essex Drive American Civil Liberties Mass Mentoring Partnership Tate Abdols Bow, NH 03304 Union of Massachusetts 75 Kneeland Street Onex Partners Advisor Inc. (603) 290-0040 211 Congress Street 11th Floor 161 Bay Street Boston, MA 02110 Boston, MA 02111 Matthew John Allen (617) 482-3170 (617) 695-2476 Toronto , ON M5J 2S1, CA American Civil Liberties (416) 362-7711 Union of Massachusetts Robert J. Ambrogi Derek Armstrong Brendan Scott Abel 211 Congress Street Law Office of Robert Ambrogi Bank of America, N.A. Massachusetts Medical Society Boston, MA 02110 128 Main Street 100 Federal Street, MC: MA5-100-09-12 860 Winter Street (508) 410-1547 Gloucester, MA 01930 Boston, MA 02110 (978) 317-0972 (617) 434-8613 Waltham, MA 02451 Travis Allen (781) 434-7682 Enterprise Rent-A-Car Shannon Ames Kristina Ragosta Arnoux Lisa C. -

A, -A EXTENSION OF

a, -a EXTENSION OF Form 990-P,F Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust oe~,~.nmf the 1r~ Treated as a Pnvate Foundation Internal Re.a 200 sav,a Note The organization may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements 2 or tax year beginning . and Name of organization Use the IRS Employer identification number label Otherwise, LIANCE FOR LUPUS RESEARCH INC . 70-G47L7L7 print Numbv and street (d P O box numbs if moil is not delivered to strml address) RoortJSiits B Telephone number orrype IZg WEST 44TH STREET 1217 212-218-2840 See Specificl City or town, state, and ZIP code C n eaamown aoolicaiion v pending ~&J% has 10 Instructions D 1 Foreign organizations, check here 1 2 Foreign oroonizationsmailing theB5961est H Check type of organization M Section 501 (3) exempt private foundation check has end altacn comoulotion ,D Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation E II privets foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J l ,ounung method = Cash DO Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from ll, Part cot (c), line 16) ] Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60 month termination column (d) must be on cash basis) under section 507 b 1)(B), check here (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment net (d) oi..eu,animta of amounts (C) Adjusted '°U'oa°'°.°".°°'°' hot I expenses per books income income 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc, received 2 , 329 , cnerxNit. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Table of Contents

CENTRAL PARK CONSERVANCY ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Table of Contents 2 PARTNERSHIP 4 Letter from the President & CEO 5 Letter from the Chairman 6 Letter from the City of New York 8 Central Park’s Impact 10 CRAFTSMANSHIP 12 Restoring the Ramble 16 Rebuilding Bernard Family Playground 18 Renewing Billy Johnson Playground 20 Reconstructing Central Park’s Perimeter 21 Restoring the West 86th to 90th Street Landscape and Perimeter 22 STEWARDSHIP 24 Operations 26 Visitor Experience 28 Volunteers 30 HELPING OTHER PARKS 32 Central Park Conservancy Institute for Urban Parks 34 Supporting New York City’s Public Spaces 36 FRIENDSHIP 46 Women’s Committee 48 The Greensward Circle 50 FINANCIALS 74 SUPPORTERS 118 STAFF & VOLUNTEERS 128 CENTRAL PARK CONSERVANCY MISSION, GUIDING PRINCIPLE, CORE VALUES, AND CREDITS Cover: Aerial view of Central Park. Left: Troy Lamb 5 1 CENTRAL PARK CONSERVANCY TABLE OF CONTENTS Partnership From the President & CEO From the Chairman It is an honor and a privilege to have been chosen to serve 36-acre woodland landscape at the heart of the Park’s It has been an exciting year for the Central Park landscapes and facilities suffering from long periods of as the President & CEO of the Central Park Conservancy historic design. We also reconstructed several playgrounds, Conservancy as we welcomed our new President & CEO, neglect and transformed them into essential recreational at this exciting time. The magnificent restoration of Central including Bernard Family Playground, with its idyllic setting Elizabeth W. Smith. Betsy’s vision to lead the Conservancy open space and amenities. I am excited to see the Park is a testament to the expertise, care, and commitment across from the Harlem Meer, and the beloved Billy Johnson beyond its founding era and focus on the sustainability of enormous impact this beautifully conceived project will of the Conservancy and its family of supporters. -

Spring and Summer

Mrs. Whitney's Miss C. Delafield, PERSONAL INTELLIGENCE. MISS STEVENS OF CASTLE POINT GEN. COWANS, BRITISH LOST AND FOUND. DIED. MOW YOHK. WAR LEADER, IS DEAD Wearing Apparel. : .i-RRACH.Bradford, at April 1#. in the :«y»»rEii,z^b't«V»S' Fit Shown Leader in Mr. and Mrs. Vincent Aator, who re¬ ENGAGED TO EDWARD B. CONDON LOOT.About 10 A. M. Saturdav. Apr!! IB neral eerV.ce* a.t Trinity C*»rcli,^'..,?*Vtz£E.lza- Politics, as on *t SculptureSy turned last week from Bermuda, are at Served Quartermaster-Gen¬ uetwe«n 1«7 East 80th at. aod Lexington beth. Mouday afternoon. AprU 1#. ?heir Rhlnobeck house. eral in World Conflict. av. arid 7*th at., large skunk collar, with 4 o'clock. in to Wed limn* partly ripped out. Reward If returned Paris, Praised Engaged !o above addi>m« Gen. Horace Porter, who celebrate^ Mintonc, France, April 16..Gen. Sir his will LOS'I Sealskin nee kplece, near the Mai! eighty-fourth birthday Friday, John Steven Cowans. 58 years old, a Frid*>': rew,irJ* FLAOg! i{o to Greenwich, Conn., In June for the member of the British Army Council r&.-v^^VTw5^,v. on Monday. April 18, at 8 F. M. Luxembourg Curator PJaces Sewetary to Aldermanic Presi¬ summer. 145*'\vr*M(thark' Ed*erl>. Oscar M. during the European war, died hero to¬ tats, Dogi, Ac. day. FLOYD.-On April 15. a*.> 7« Hor in First Bank of Amer¬ dent to Become Bride of It. n-ral ^orf".Morrttt Btarlia .*« Mr. an1 Mrs. Charles L.